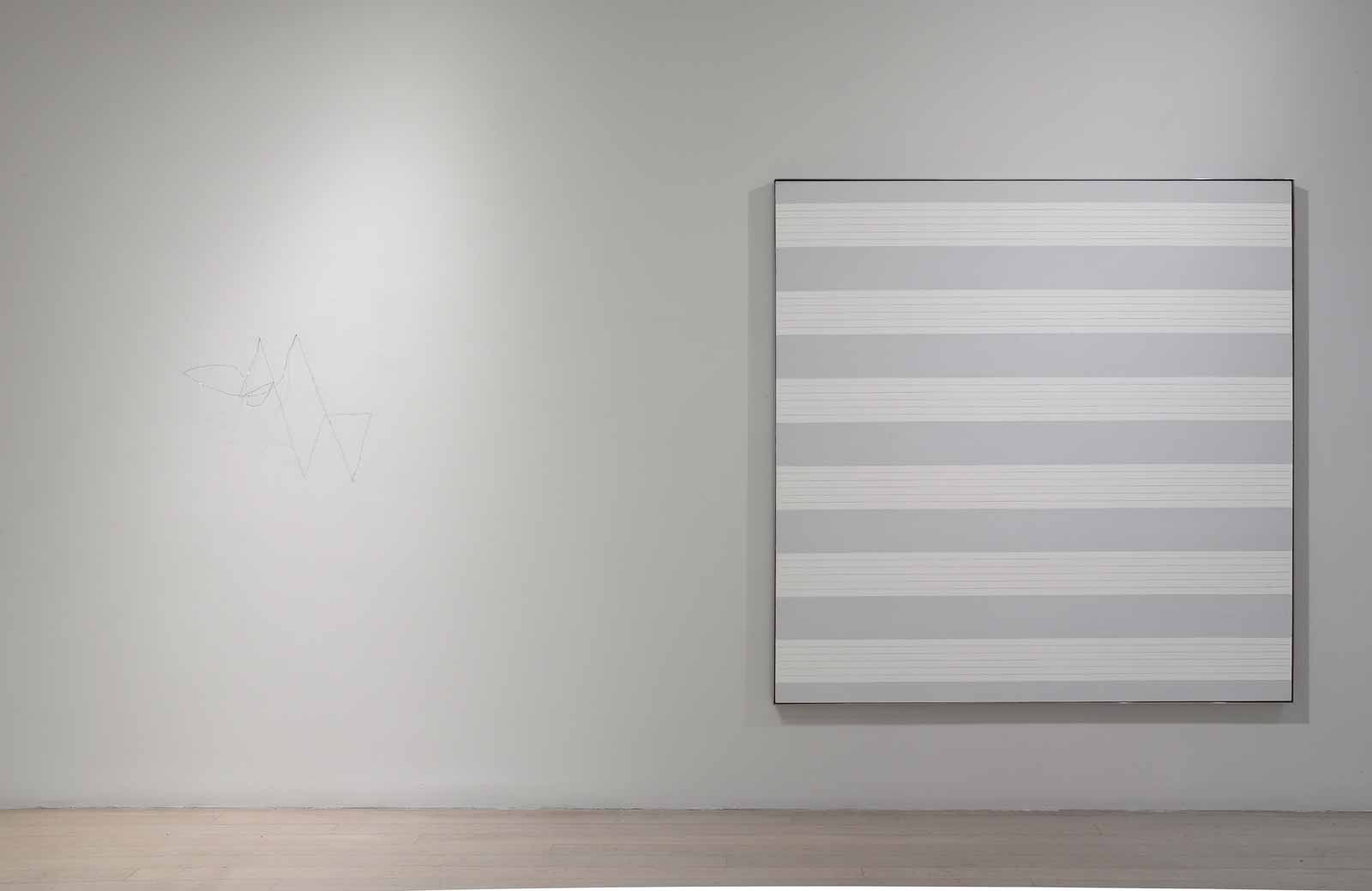

Photo by Kerry Ryan McFate/Pace Gallery/Estate of Agnes Martin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Richard Tuttle

Richard Tuttle: 20th Wire Piece, 1972/2017; Agnes Martin: Untitled #4, 2002; Richard Tuttle: 45th Wire Piece, 1972/2017, from “Agnes Martin, Richard Tuttle: Crossing Lines,” Pace Gallery, New York, 2017

Art history was born as a process of comparison: the stiffness of an early Greek kouros compared to the natural pose of a later figure; side-by-side images clicking into place from whirring lantern slide projectors; the hackneyed term “juxtaposition” that launched a thousand essays. At Pace Gallery’s “Agnes Martin, Richard Tuttle: Crossing Lines,” Tuttle, channeling Martin, introduces a different concept, which he calls “augmentation”—a relationship and exchange between two artists’ works that goes beyond simple comparison. This is not the first time similar works by these artists have been shown together, including at Documenta 5 in 1972, in Paris in 1992, and in 1998 at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, all while Martin was still alive. Some two decades later, Tuttle extends the line at Pace—as if augmentation allowed relationships to continue developing in art even as they must inevitably end in life.

Looking at Agnes Martin’s paintings, one has the sensation of bright sunlight on a bitterly cold day—it’s difficult to see anything else. At “Crossing Lines,” you almost miss Tuttle’s work altogether until your eyes adjust. Seven pared-down abstractions by Martin form a concise arc of her mature career, from Untitled, a mesmerizing 65-by-65-inch oil on canvas (circa 1960), to Untitled #4 (2002), one of her final five-by-five-feet acrylic and graphite paintings. (Martin died in 2004.) The only color in the show is the yellow cream line of the receding frames of the earliest canvas, which breaks from its Albers-esque homage into an arresting dark circle. All of the other paintings fall on a pencil-hued spectrum, from the faintest No. 2 mark to the deepest charcoal smudge.

Interspersed between the canvases are suspended tangles and tines of metal: once Martin’s paintings were hung, Tuttle worked in situ on eight new wire pieces to accompany them. (He began this series in the 1970s; each work is dated 1972/2017.) Most of the wire pieces appear on an adjacent wall that is perpendicular to Martin’s paintings, suggesting a subtle correspondence rather than a side-by-side comparison. Tuttle describes the composition of his pieces as an “activity.” Pencil lines are drawn directly onto the wall, and then a thin wire attached with a nail on or near the line’s endpoint and stretched directly, or bent into multiple loops and angles, to the line’s other endpoint, never much farther than an arm’s span or much larger than a tumbleweed. The shadow is considered part of the piece; it is often its most visible component.

“Relations often invite comparison, an idea I learned from Agnes Martin, who could decline showing for this reason,” Tuttle wrote in a statement for the exhibition. “For me, comparison, in this case, is outweighed by an augmentation, where the access to each artist’s work is facilitated, indeed, enhanced, by the other’s, so many of the issues, present for each artist, shown in a necessary compliment, otherwise left open and blank.”

The statement is opaque; there is that compliment rather than the expected complement, a wonderful slip of phrase, or praise. Augmentation seems too baroque a word for the correspondence between these artists, one living and one dead, both of whom have made work that is self-consciously modest, though each not without its own signature marks. Augmentation is also an unexpected term for art that channels just the opposite: evacuation, stripping down.

Tuttle has made a career of deceptively simple work. His “pieces” and “reliefs” are not quite painting, not quite sculpture, and often marshal very pedestrian materials for elegant ends. (Elmer’s Glue, thread, and paper clips feature prominently in his 100 Epigrams, not to be missed in the small gallery upstairs at Pace.) His 1975 show at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art, which included some wire pieces, created a controversy because of its extreme unobtrusiveness, with visitors unsure where to even find the art in the galleries. (Describing “a stick of wood rising from the floor” and “some bits of string arranged on the rug,” Hilton Kramer’s scathing New York Times review contended that “less has never been as less [as] this.”)

“Simplicity is never simple,” Martin explained, as if in reply, in an interview about Tuttle in 1997 on the occasion of their joint exhibition in Fort Worth. The risk of simplicity is that it demands perfection: there is nowhere to hide, no thing to hide behind, and so each element must be exactly so. Or, as Tuttle described the disciplined minimalism of Martin’s line, “An artwork is the only thing we have where we can capture everything that it is we need and eliminate everything it is that we don’t need.”

Advertisement

And so augmentation in practice can underscore its very opposite—the bare bones essentials of a thing, rather than an addition. In this exhibition, the economy of line so central to both artists’ works is highlighted by seeing the two artists’ works together. Both Martin and Tuttle extend drawing to a new material dimension, whether on the rough textile surface of canvas or in the space reaching from the wall of the gallery.

Tuttle’s elusive works riff on the most remarkable aspect of Martin’s paintings: the thin pencil line that is the scaffolding of their images, whether bands of tonality, exact grids (in the case of the tight rule of Leaves, 1966) or looser, cloudy washes (as in Untitled, 2002). The wire and pencils mirror the paintings’ grayscale. These materials even seem to allude to the way that Martin made her horizons: tracing pencil along masking tape or a piece of string pinned across the canvas’s width. (Tuttle’s wire also resembles Martin’s looping script, best seen in the facsimiles of her writing in Arne Glimcher’s lavish 2012 Agnes Martin: Paintings, Writings, Remembrances.) And augmentation goes the other way, too: Martin’s paintings give Tuttle’s wire pieces a grounding, a grid to reach for, another measure of reality to consider.

Tuttle’s theory of augmentation came out of a creative process that is both collective and also solitary: he enters into the space of another artist and amplifies its fundamental experience. (Thus the brilliance of the barely perceptible wire pieces alongside Martin’s blinding glory.) “Crossing Lines” is that rare show that focuses on how certain artists’ mutual influence takes form outside of neat chronological order. And to have a man responding to a woman’s work is refreshing; to have that response be as far from mansplaining as one can imagine—more like notes of admiration—is moving. In fact, Tuttle recently edited and illustrated a book of Martin’s gnomic writings, Religion of Love (2016).

Tuttle was twenty-four when he first contacted Martin in New York to see if he might purchase one of her drawings (as it happens, her first with an all-over grid), and a forty-year friendship began. Almost three decades separated the two; she was born in 1912, a contemporary of the Abstract Expressionists, Tuttle in 1941, a contemporary of the Minimalists. Both artists embrace a perceptual sensuousness one might associate with Abstract Expressionism, and a disciplined spareness one might expect from Minimalism, though neither really fits into either category. Martin’s mature period began in New York in 1957 when she was already in her forties. Living in an old sail-making loft just below Ellsworth Kelly at the southern tip of Manhattan at Coenties Slip, she began to explore her now well-known large abstractions.

The Pace show is a tributary of that earlier wellspring of communal creativity. The brief but fertile tenure of artists at the Slip underscores the creative value of a group built on the collective support of each artist’s creative solitude. In its location on the edge of the East River, as close to nature as one could get in the city, and as far from the competitive maneuverings of so much postwar American art, the Slip was an essential site for Martin’s development as an artist; in addition to Kelly, her neighbors included Jack Youngerman, Robert Indiana, Lenore Tawney, and James Rosenquist, with Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg just around the corner. This group of influential American artists didn’t form a movement, and the work that came out of these studios could not have been more varied: sculpture and painting, pure abstraction and representational Pop, film and textiles. (Martin even made some wood and nail assemblages, most of which she destroyed.) But the Slip was a space where artists could work independently while often corresponding and contributing to each other’s works in a way that clearly inspired Tuttle’s idea of augmentation.

The fifteen spare works of “Crossing Lines” embody the spirit of this world. The show’s title describes the grid drawing that Tuttle bought from Martin in her downtown studio in 1964 in relation to the shadows his wires draw moving along the wall at Pace. The title demonstrates that proximity does not signal simple equivalence. “Crossing Lines” can mean a juncture between two fields of work; a point of meeting even though each line is heading in a different direction. It can even be the mistaken communication of crossed wires. It can suggest the perceptual boundaries we traverse as viewers, too, to really see something: Martin once said that a painting should be “the simple, direct going into a field of vision, as you would cross an empty beach to get to the ocean.” That is one of the thrills of the show’s economy—how many different ways one line can bend toward and away from another.

Advertisement

“Agnes Martin, Richard Tuttle: Crossing Lines” is at Pace Gallery in New York through January 27, 2018.