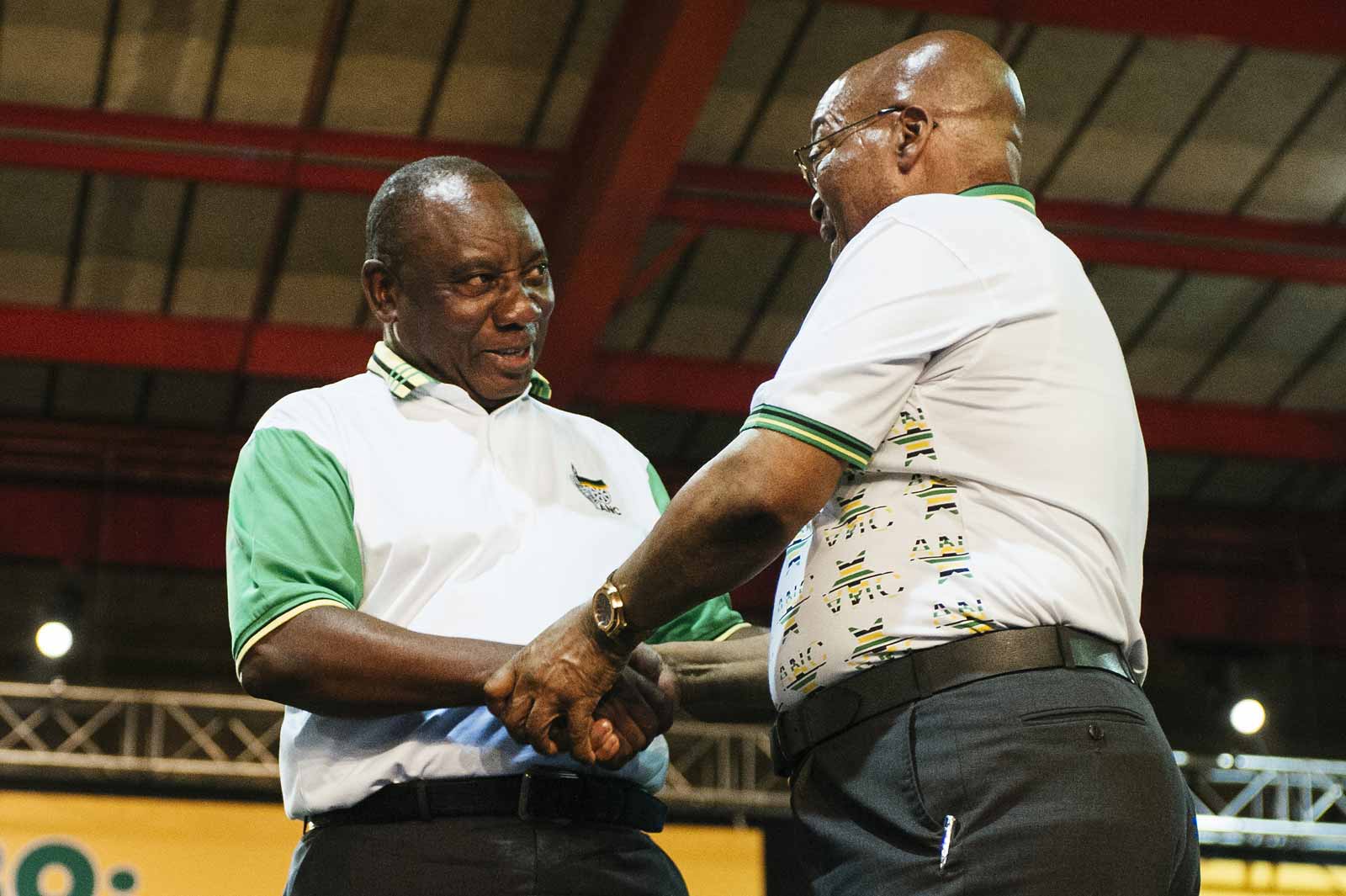

Last Monday in Johannesburg, Cyril Ramaphosa, one of South Africa’s wealthiest men, narrowly won a party election to succeed the corrupt and compromised Jacob Zuma as president of the ruling African National Congress (ANC). This puts him in line to become the country’s fifth democratically-elected president. Many think he should have been the second: he was Nelson Mandela’s preferred heir, but was displaced by Zuma and his predecessor, Thabo Mbeki, in 1994. He has been playing the long game ever since.

Zuma’s term as president of the country does not end until mid-2019. But Ramaphosa could unseat him within weeks—and get him prosecuted and, potentially, put behind bars. Will this happen? Can it happen? These are the questions we South Africans are asking ourselves, as we try to work out what kind of leadership Ramaphosa will bring to his decaying party and our troubled land.

Ramaphosa is a Soweto homeboy, the son of a police sergeant, who now lives in a grand home in Hyde Park, one of Johannesburg’s wealthiest suburbs. He qualified as a lawyer—no mean feat in apartheid South Africa—but his roots are in the labor movement and he played an important part in the downfall of the apartheid regime, mobilizing mineworkers. He has long been an avid fly-fisherman and now owns a cattle-ranch. When I profiled him for a South African newspaper in 1996, just after he left politics and joined the country’s largest new black-owned business, New Africa Investments, I described him as “charming and unflappable, entirely in control”:

There’s that smile that wraps itself around his face, that conspiratorial baritone chuckle, that constant engagement masking profound reserve. The most astonishing thing about an encounter with Cyril Ramaphosa is that, even though you know he’s spinning you a line, you—oh, hapless trout!—go for the hook anyway.

I have followed Ramaphosa’s career for three decades. I was astounded by his skills in the 1990s, when he led the ANC’s negotiating team, thrilled at the possibility that he would be Mandela’s successor, and then disappointed by his hubris when he flounced out of politics: he refused, even, to attend Mandela’s inauguration in 1994. When I wrote that profile two years later, I was warily interested in the way he was leveraging his political credibility to gain a place at the high table of industry, as a beneficiary of the official policy of “black economic empowerment.” But some fifteen years later, in 2012, I was—like so many South Africans—distressed by the way he used his political connections to insist that the police take action against a wildcat strike at a platinum mine in which he held a stake. In the resulting “Marikana massacre,” thirty-four striking miners were killed by police, in an echo of the 1960 Sharpeville shootings.

Ramaphosa was exonerated by a judicial commission of enquiry, but his unseemly role at Marikana became an indicator of the extent to which he had sold his soul. That he has bounced back from this low point demonstrates both his resilience and the broad-based antipathy within the ANC toward Zuma at the moment. Those who voted for Ramaphosa understand that Zuma and his kleptocratic circle need to go if the ANC is to endure, and if the country’s economy is to have any hope of growth. Ramaphosa has, indeed, made millions parlaying his political credibility into assets, but there has never been an allegation of corruption against him; and the principal lieutenants in his election campaign—leading ANC figures like the former finance minister Pravin Gordhan—have a solid reputation as reformers, modernizers, and straight arrows.

Ramaphosa’s relationship with Zuma (and Zuma’s predecessor, Thabo Mbeki) has been fraught. Although Mbeki and Zuma, then in exile, had negotiated Nelson Mandela’s release in 1990, Ramaphosa and his radical supporters thought the duo too soft; with brutal efficiency, Ramaphosa succeeded in sidelining them and taking over the reins of the talks himself. Ramaphosa, the labor leader, was a tough negotiator, unafraid of brinkmanship, but he also loved the finer things of life and he developed a rapport with his white South African counterparts that helped to usher in democracy. For a while, Ramaphosa was everyone’s hero—except for those ANC comrades around Mbeki and Zuma.

Mandela made it clear that he wanted Ramaphosa for his deputy, but the old man was outfoxed by Mbeki and Zuma. So began a dynasty of diminishing returns: Mandela appointed Mbeki as his deputy in 1994, and then, when Mandela retired in 1999, Mbeki appointed Zuma in turn. It seemed that Ramaphosa was done with politics, but no one who knew him doubted his ambition—or his need to salve the personal wound of his 1994 ejection. Once Thabo Mbeki and Jacob Zuma fell out with each other (Mbeki fired his deputy over an earlier round of corruption allegations), Ramaphosa reappeared on the political scene as one of the “coalition of the wounded,” as they were known, that moved to replace Mbeki with Zuma as the party’s president in 2007. Ramaphosa then led the charge to fire Mbeki as president of the country, in 2008, on the grounds of his alleged meddling in the criminal case against Zuma.

Advertisement

With Mbeki gone, and in uneasy coalition with Zuma, Ramaphosa began again to cultivate his political base. In 2012, he was elected by the party congress as Zuma’s deputy in the ANC. Following a precedent that had become ANC tradition, Zuma duly appointed Ramaphosa as deputy president of the country. Ramaphosa assiduously defended Zuma, and once more, I found myself perplexed by the man I had once admired: How could he keep singing the praises of his venal boss? Was he still playing the long game, or had he succumbed? Was he so intent on attaining power at any cost that he would not take a stand against the naked abuse of power that was happening under his watch? He was the deputy president, after all.

At last, in December 2015, Ramaphosa made his play. He finally found his voice when President Zuma fired the finance minister, Nhlanhla Nene, for refusing to rubber-stamp proposals, including an outrageous nuclear deal with Russia that threatens to bankrupt the country, that were clearly designed to enrich Zuma and his cronies. Zuma replaced the respected Nene with a provincial no-namer, the rand crashed, and Ramaphosa began campaigning to be the next leader on an anticorruption ticket. This meant pitting himself against Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, who had already been selected by the Zuma faction to succeed her ex-husband. Zuma and his ex-wife had gone through a bitter divorce and not spoken for years, but they share children and seem to have reconciled.

Dlamini-Zuma is a seasoned politician, and was a competent cabinet minister for many years (health, foreign affairs, home affairs) before going to Ethiopia to run the African Union. But she is also an ideologue, with black-nationalist roots, who has espoused a left-wing policy of “radical economic transformation,” including state-led economic growth. Although there is no whiff of corruption about her personally, it was hard not to see her platform as populist cover for continued plunder—given the Zuma coterie that was backing her. In his recent book The President’s Keepers, the investigative journalist Jacques Pauw disclosed not only the extent of the rot around Zuma—especially in the state security and revenue services—but also that his ex-wife’s campaign was financed by a particularly unsavory set of cronies: tobacco smugglers scheming to get around the import duties that are arguably part of Dlamini-Zuma’s most enduring legacy, as an anti-smoking campaigner.

Ramaphosa’s New Deal platform, self-consciously borrowed from Franklin D. Roosevelt, was low on detail, but hewed toward the center, and advocated partnerships between government, business, and labor. During the campaign, Dlamini-Zuma and her supporters worked hard to tar Ramaphosa as a stooge of “white monopoly capital,” that old ANC foe. She came very close to winning: with the backing of 2,261 delegates, she was only 180 votes short of victory; Ramaphosa won with 2,440.

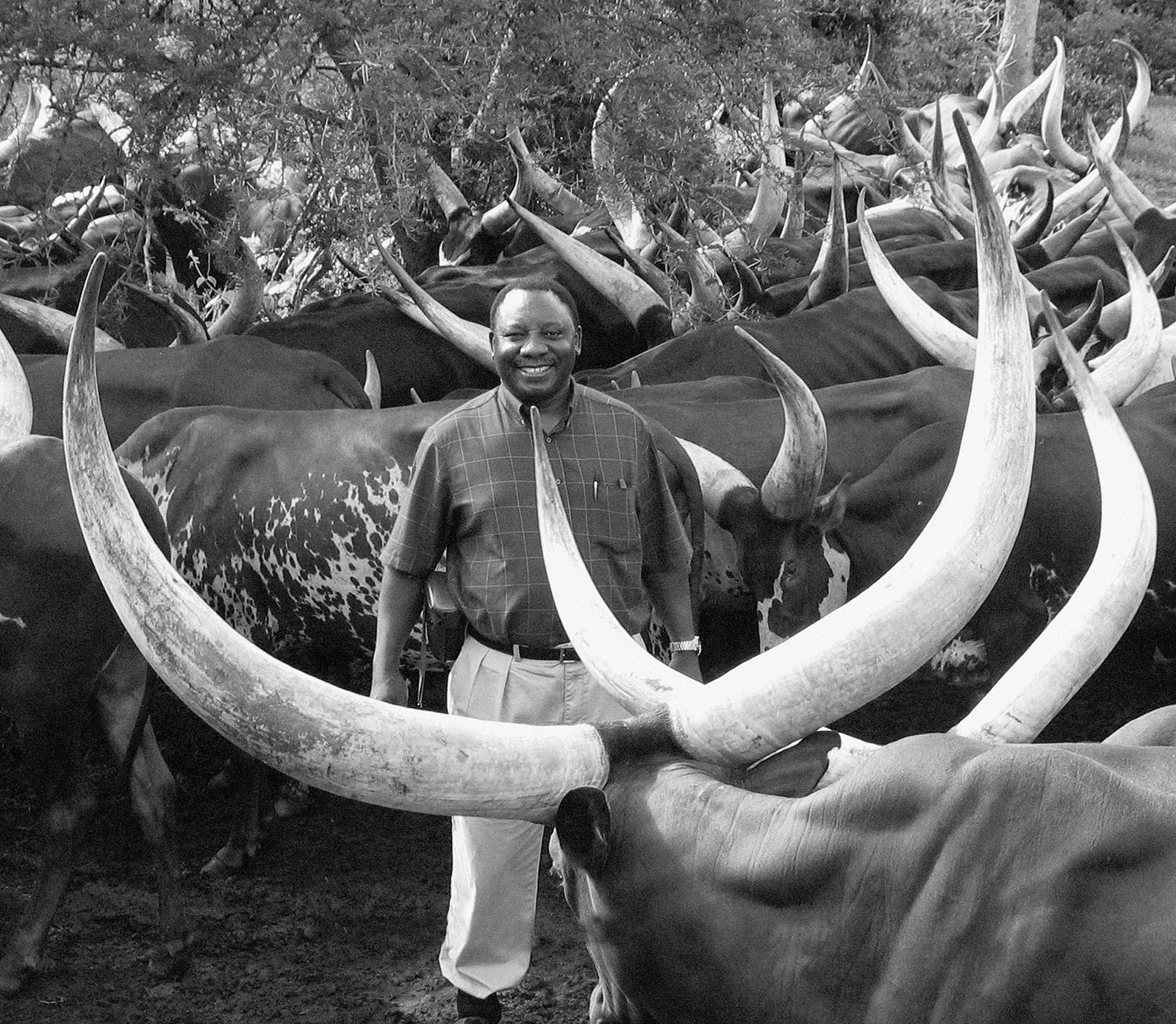

Considering the presumed taint of “white monopoly capital” and the Marikana massacre, Cyril Ramaphosa made an odd decision in the heat of his campaign. At his sixty-fifth birthday party last month, attended by both his industrialist friends and his political comrades, he launched Cattle of the Ages, a lavish coffee-table book about his great obsession (besides political power). The book retails at 850 rand (about $40, a large sum in this country): with photographs by the renowned South African photographer Daniel Naudé, it documents the herd of long-horned cattle Ramaphosa had imported from Uganda and now breeds at his ranch on the Mpumalanga escarpment, east of Johannesburg. The Ankole are “the most magnificent breed of cattle in the world,” Ramaphosa writes; they had lit an “unexpected fire in my heart” ever since he’d seen them on a visit to the ranch of the Ugandan dictator, Yoweri Museveni, in 2004.

The Ankole are known as the “Cattle of the Kings”; their extravagant horns curve into regal arcs. Ramaphosa now has over a hundred of these animals; one of his bulls recently fetched more than $50,000 at auction. When one looks at the quantum of wealth, Jacob Zuma’s improvements to his rural homestead, funded illegally from the public purse, seem tawdry by comparison. Ramaphosa’s investment may be ostentatious, or canny, but he proclaims loftier motivations for it. At the launch, he spoke of how he had chosen to call the book Cattle of the Ages rather than Cattle of the Kings because of his egalitarian ambitions for the beasts: he plans to loan his animals to developing black farmers to help them improve the bloodlines of their own stock.

Advertisement

Even if these regal cattle and this glossy book are signs of swagger, or hubris, Ramaphosa has always been intensely conscious of his image. I have no doubt that there is a plan to the way he has cultivated his cattle-obsession and put it into the public domain. Released in the middle of his leadership campaign, Cattle of the Ages is Ramaphosa’s equivalent of Barack Obama’s Dreams From My Father. “Somewhere in the depths of my soul is the connection my father had to his cattle, the hills of Khalavha and his people,” he writes. “My love for cattle could be a reflection of my father in me; or some form of agency on behalf of my father, Samuel Mundzhedzi Ramaphosa,” because as “in most African cultures, cattle are a sign of wealth and stature among my father’s people,” the vhaVenda. Samuel Ramaphosa had tended his family’s herd but he had no opportunity to acquire his own, as he was forced in the apartheid era to migrate to the city for work.

At the last ANC elective conference, in 2012, the unschooled Jacob Zuma derided “clever” blacks—by which he meant people like Ramaphosa, educated and urban, disconnected from their roots. Through his cattle, Ramaphosa seeks to demonstrate a reconnection with the land and the heritage of his people. And by promising to share his superior Ugandan stock with lesser herdsmen, Ramaphosa is implying that, unlike his parochial predecessor, he is both a pan-Africanist and a progressive. The final piece of his symbolic presentation is showing that he can play the boer at his own game, even in animal husbandry, the very bastion of Afrikaner commercial agriculture. The book details, at some length, how Ramaphosa recruited the best Afrikaans scientists to use embryo transfer to circumvent strict rules about importing livestock. Once more, Ramaphosa is offering a lesson here: he can play by the rules and still get things done. He is both a technocrat and an operator.

In his victory speech on Thursday, Ramaphosa diverted from his prepared notes to address the party congress’s standout resolution: to revise the country’s constitution so that land could be expropriated, without compensation, for redistribution to black South Africans whose ancestors were dispossessed by the 1913 Natives Land Act. When black people lost their land, he said, “poverty set in, because our forebears… [had] led a fulfilled life from the land. They were able to feed their families. And when the removals and dispossession took place, poverty became a partner to the people of our country.”

The land expropriation resolution was a victory for Dlamini-Zuma’s supporters. Ramaphosa’s own platform on this, South Africa’s tinderbox political issue, was much more moderate: such expropriation could only apply to illegally-acquired land. Now, though, he did a characteristic two-step. He played to the gallery of the comrades who had elected him, but he also used a measured and reasoned tone for the banks, hedge-fund investors, and ratings agencies that hold South Africa’s economy in their hands. Redistribution, he reassured them, would be done in a way that did not harm the economy, agricultural production, or food security.

I am not Robert Mugabe, he was saying. This will not be Zimbabwe. Read my book and you will see. My own family knows the pain of dispossession. But I now own the most magnificent herd of cattle in the country, and I am a successful farmer. I have been on both sides. That’s why I can do the job.

If Ramaphosa is indeed the playmaker and reformer he has claimed to be, he faces his toughest test now, in the days immediately after his victory: what to do about Jacob Zuma. Ramaphosa knows, as do his campaign managers, that if Zuma sees out his term of office, the ANC risks losing power in 2019. Last year, the party lost control of three of South Africa’s biggest cities, including the economic center of Johannesburg and the capital Pretoria, in large part because “clever blacks” had had enough of Zuma.

Ramaphosa has grounds to move against Zuma. In 2016, the Constitutional Court ruled against Zuma for “failure to uphold the Constitution” by abusing his position over extravagant improvements he had made to his Nkandla homestead. Later that year, Thuli Madonsela, the public protector (a statutory watchdog with judicial powers), announced that there was prima facie evidence of Zuma’s complicity in what became known as the “state capture” by a business dynasty, the Guptas. Yet Zuma has seemed untouchable: although there are 783 counts of corruption and fraud pending against him, dating from a 2003 investigation, they have not seen the light of day because he put his cronies in charge of the prosecuting authority. Just two weeks ago, though, a high court in Pretoria gave Ramaphosa a handy weapon: an order that, because of Zuma’s own conflict of interest, his deputy (in other words, Ramaphosa) was to appoint the new national director of public prosecutions. The new appointee will be the person who decides on whether the case against Zuma is to proceed.

If Ramaphosa had lost the ANC election to Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, Zuma would surely have fired him and appointed another, more compliant deputy (perhaps his ex-wife, indeed). Zuma would most probably have stayed in office for the remainder of his term, and out of jail indefinitely. But Ramaphosa won the party’s mandate, so for political reasons Zuma cannot fire him as deputy president of the country (even though it is technically within his executive authority to do so). The speed with which Ramaphosa selects a new director of prosecutions, and the quality of this appointment, will be one of his first tests.

There is no question that Ramaphosa and his supporters want Zuma out of office as soon as possible, but there is disagreement in his camp about what to do next. Some want Zuma behind bars, as a sign to South Africans that his kleptocratic era is over, and that the rule of law has been re-established. Others feel that this would be politically imprudent, and they propose striking a deal: if Zuma resigned of his own accord, he could be left in peace.

The hard truth is that such a deal might be the best outcome South Africans can hope for. Not only was Ramaphosa’s margin of victory in the party leadership election narrow, but the slate of leaders elected alongside him also seems almost evenly divided between his partisans and supporters of the Zumas. Even if a corruption prosecution against Zuma went ahead, Ramaphosa cannot fire the country’s president without majority backing from the party’s 110-member national executive committee.

There is no guarantee Ramaphosa would get such support. After this week’s elections, the most powerful man in the party after Ramaphosa is its new secretary-general, Ace Magashule, a Zuma crony deeply compromised by his own relationship with the Gupta family. Magashule has been the regional strongman in the rural Free State province for the past twenty years, and its premier for the past eight: he has run the province badly, but firmly, and built a bulwark of local power. Similar in profile is the man elected as Ramaphosa’s deputy, David “D.D.” Mabuza, who rules the Mpumalanga province with a mix of patronage and thuggishness, and has several allegations of political murder against him.

Mabuza has showed particular cunning. He built up the party membership in his small home province so that he could bring a large number of delegates to the conference and thus assume the part of kingmaker, playing both sides in a quest for national power. Although nominated on Dlamini-Zuma’s slate as her deputy, he apparently did a last-minute deal to deliver victory to Ramaphosa.

Mabuza and Magashule both have their own loyalists in the Zuma administration, senior henchmen who are themselves mired in the Zuma web of corruption. Whether these tainted cabinet ministers make it into a Ramaphosa government—indeed, whether Mabuza himself does, or simply remains a party official and a provincial premier—will indicate how much real power the new ANC president has, and if he is willing wield it. But if party “tradition” continues, and Mabuza slides into place as Ramaphosa’s successor, the worst of the ANC will prevail, and the party will continue its downward trend to defeat and disgrace. Ramaphosa has some herding to do.