A blonde, hugely buxom woman is pictured standing in her home, the largest in the United States. Her maid is in the corner of the frame and one of her eight children is in the maid’s arms, his face covered in neon-orange Cheetos crumbs. In another image, underdressed dancers gyrate while a lottery winner “makes it rain” at a strip club, dollar bills flying. In Moscow, a Latvian model/trophy wife stands in front of her home’s giant library, composed entirely of her self-published fashion photography books. An American child beauty queen wears a smog-thick layer of make-up and a saloon-style boa and headdress. Her tongue rolls between her teeth salaciously.

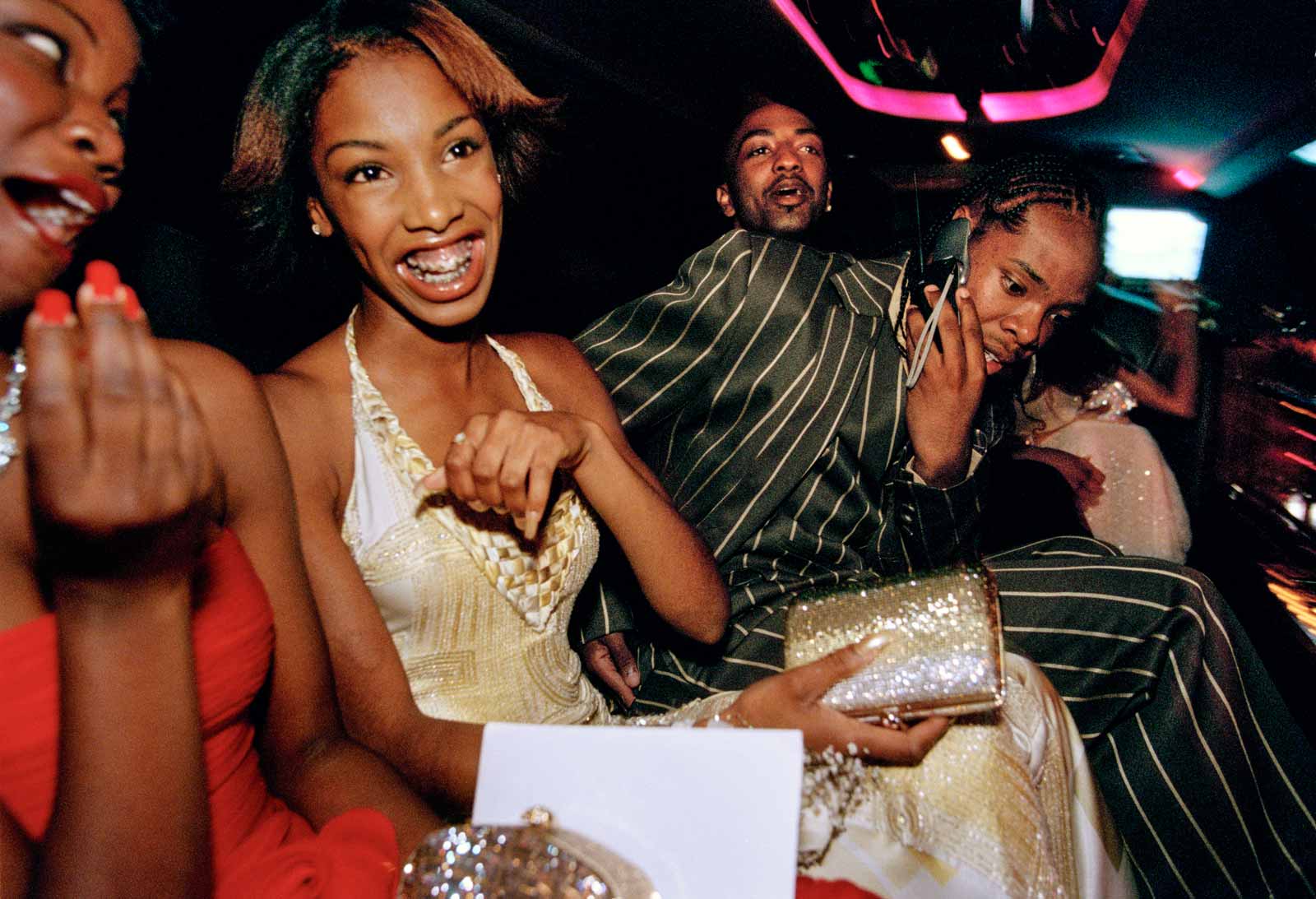

These photos by Lauren Greenfield, who has been documenting American exorbitance for decades, are part of “Generation Wealth,” an exhibition of some 200 images at New York City’s International Center of Photography through January 7. (A feature-length Amazon-supported documentary by Greenfield on the same topic, not included in the show, opens at Sundance later this month.) Greenfield’s subjects are not only America’s wealthiest, but also the striving wannabes who go into hock so they can mimic their social superiors with pricey cars and weddings they can’t afford. As Greenfield has said in an interview, her work depicts “bling” as “the new American dream.”

Greenfield’s raw material, materialism, is candy-colored and stimulating. It is also almost uniformly depressing. She shows us the self-starved bodies of the affluent young, among their parents’ magma-flow of possessions. We see their marmoreal homes, their beauty regimes, and their fathers’ younger, heliotropic second wives. The overall affect of the exhibition’s packed two floors and the accompanying book, a dense gold brick with some 650 images that was so big it actually took up too much space in my home, is nihilism. At times, it even feels gleefully so.

Greenfield and other photographers focused on documenting America’s rich form a counterpart to the many now shooting in Detroit or America’s Methlands, in full, gritty, and lambent detail. On either side of this divide, photographers seeking to represent our steep income gradient face potential pitfalls. On the one hand, photographers who find an inadvertent beauty in abandoned lots, mortgage-collapsed suburban dwellings, or the homeless run the risk of creating “ruin porn.” On the other side, photographers of the wealthy may be guilty of making what could be called “bling porn”—when grossly gilded worlds are turned into art that is itself grossly gilded. In other words, bling porn happens when artists make luxury objects out of the luxurious lives and objects they ostensibly seek to critique.

Bling pornographers may assume a censorious attitude toward their decadent subjects and their displays of branded goods, but their glossy prints can themselves become decadent products for art buyers’ consumption. Earlier examples of this are Jessica Craig-Martin’s party snaps, cropped to remove faces, or Tina Barney’s Nantucket-palette images of families and preppy kitchens. (An exception to this problem is the work of Magnum photographer Jim Goldberg; in Rich and Poor (1985), his quiet black-and-white portraits are not trying to be exciting.) At times, Greenfield’s work, too, approaches bling porn not just because her works are sold for profit to the wealthy, but also because of the high gloss and lush colors of her images: the lifestyles of grotesque celebrities like Tyra Banks, Brett Ratner, and Donatella Versace are portrayed with a vibrancy that can seem to foster the dream of a 90,000-square-foot home (which was the plotline of her 2012 film The Queen of Versailles) rather than satirize it.

There are two critiques of Greenfield’s work that tend to circulate. One is that the work can be perilously close to becoming a gaudy display of the allure of privilege, including Greenfield’s own, which has given her access to the world of the wealthy. The other is that, as the New York Times review had it, Greenfield is guilty of “preferring easy satire if not outright mockery” to a more complex portrayal. Leafing through the book does sometimes put one in the uncomfortable position of consuming consumption, being shoehorned into the bling-porn point of view. Take that Latvian-born model in Moscow wearing a sweater that reads, “I’m a luxury,” like a dead-eyed animatronic Odalisque, Westworld by way of Riga. These and other images like it are undeniably gross, yet also as seductive as a fashion shoot.

But the risk of bling porn is worth taking to bear witness to our new Gilded Age. The recently-passed tax bill is only the most recent example of how income inequality has been written into the law of the land. Our president and first lady routinely celebrate their own excess in photographs, as does Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin and his rapacious wife, who famously posed with sheets of cash. America’s three wealthiest billionaires now possess as much wealth as the entire bottom half of US households. Since the Great Recession of 2008-2009, more than 85 percent of income gains have gone to the top one percent. The lifestyles of the rich and famous are amply celebrated in the real-estate sections of newspaper, in glamour magazines, and on reality television, giving their cues to the amateur snappers on social media, like Rich Kids of Instagram or Private School Snapchats.

Advertisement

“Bling porn” thus captures our moment. Its paradoxes, however, are as old as portraiture. As John Berger wrote some forty years ago in Ways of Seeing, even the Old Masters’ paintings were coated in the temperas and oils of ideology, including the worship of Mammon. Oil painting celebrated a new kind of wealth, wrote Berger, wealth that was all about buying-power. Painting “itself had to be able to demonstrate the desirability of what money could buy,” Berger wrote. “And the visual desirability of what can be bought lies in its tangibility, in how it will reward the touch, the hand, of the owner.”

Like those floor-to-ceiling nineteenth-century portraits of robber barons, some of Greenfield’s images are supersized in strikingly large prints, echoing her quarry’s inflated tastes. The exhibition includes many smaller prints, video consoles, a short documentary (whose scalding commentary by the artist is bizarrely accompanied by a light-hearted, reality TV-style soundtrack), and extensive commentary written by some of the subjects (one, dressed in princess garb, regrets that, back in history, one had to be born a princess).

Some of the best pictures show how far the aspirations and tastes of the one percent have trickled down, infecting not only the middle class but working people of all types. They, too, want to live the American fairytale more than the American dream—like the service worker who scrimped and saved in order to afford a Disney wedding where she was transported in a glass carriage, replete with footmen in powdered wigs.

The twisted fairytale has been a mainstay of Greenfield’s projects since the 1990s. Her first book, Fast Forward (1997), includes photographs from the opulent private high school that Greenfield herself attended in Santa Monica, with its parking lot full of BMWs, or teenagers getting nose jobs to match their friends. Greenfield’s second book, Girl Culture (2002), extended and concentrated her look at youth and commercialization, focusing on girls in particular. I first encountered this work when I was also documenting the startling excesses of mall-rat teenagers and bar mitzvah parties replete with sexy adult “party starters” paid to dance breast-to-nose with thirteen-year-old boys for my first book, Branded (2004). The coming-of-age party became a process of what I dubbed “self-branding” in the late 1990s, by which adolescents internalized the external ad campaigns aimed at them. Greenfield’s images of teen girls suggest that her subjects experience themselves as much by consuming products as they do being consumed by men who see them as mini-beauty queens or strippers. Greenfield was the grand interpreter of this transformation of youth, although I related more to other photographers of the period working in this field—for example, the Dutch photographer Rineke Dijkstra, who appeared to have greater sympathy for her body-crazed adolescent subjects.

Greenfield’s photography of young celebrities was sometimes premonitory, like her snap of a youthful Kim Kardashian. Her early images of aging women overdosed on cosmetic surgery feel similarly prophetic, as procedures overall have increased 115 percent since 2000. The women pictured are by no means, all “ladies who lunch.” One of Greenfield’s most disturbing recent “surgery” portraits shows a woman bus driver who underwent multiple procedures on her small salary. In these photos—for example, in a striking close-up of lips being injected with collagen, there is a shockingly toxic picture of gender oppression plus money.

The world Greenfield documents feels hermetically-sealed and suffocating. Only a few portraits even suggest there could be something beyond all this decadence and moral decay. Among them is an Icelandic fisherman-turned-banker who returned to fishing cod and a happier life.

Advertisement

The weakest works in “Generation Wealth” are photographs of Wall Street titans and of China’s new rich. One feels Greenfield included these images because they jibe with her theme, not because there is anything else particularly astute or striking about them. There is a similar vacancy in some of Greenfield’s shocking images of the super-rich: Who really cares about these people? They never had souls. It’s the working-class Disney “princess” who could still be “saved” that seems more poignant.

At its best, Greenfield’s work provides a shocking, rigorous, and needed visual language for society’s worst excesses. A decade ago, to visit this world might have seemed like cultural anthropology. It might even have been an optional exercise. Today, in the age of Donald, Melania, and the Mnuchins, it is a necessary, even captivating, task—if, at times, a repulsive one.

This essay was supported by the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

“Laura Greenfield: Generation Wealth” opened at the Annenberg Space for Photography and is now on view at the International Center for Photography in New York City through January 7. The book by the same title is published by Phaidon.