He may not be altogether “crazy,” but he is so:

[…] unstable a personality as to be quite vulnerable to certain kinds of psychological pressure. The outstanding neurotic elements in his personality are his hunger for power and his need for the recognition and adulation of the masses. He is unable to obtain complete emotional gratification from any other source.… Whenever his self-concept is slightly disrupted by criticism, he becomes so emotionally unstable as to lose to some degree his contact with reality.… [His] egoism is his Achilles heel. The extreme narcissistic qualities of his personality are so evident as to suggest predictable patterns of action during both victory and defeat.

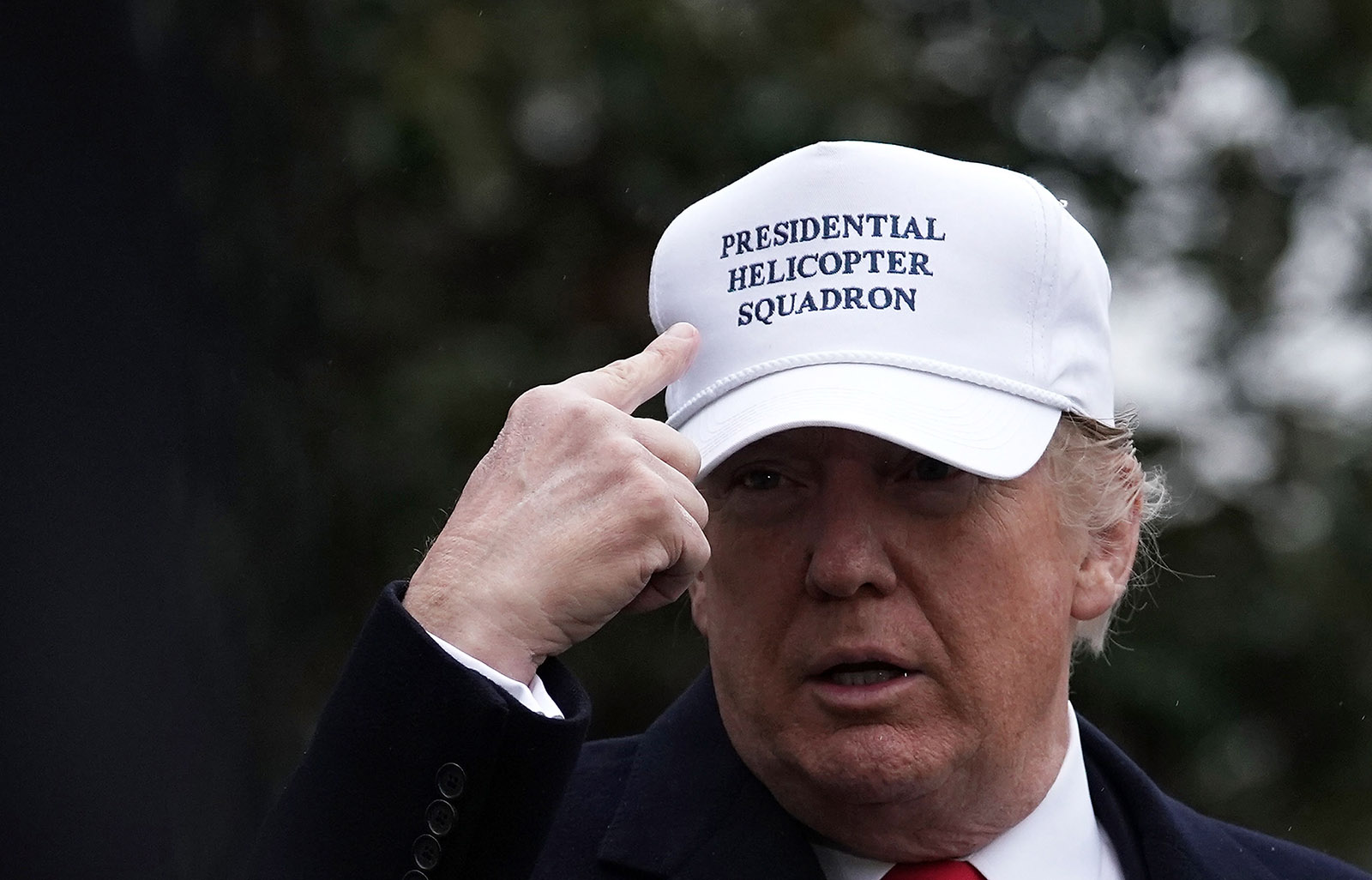

This is not a psychiatric assessment of Donald Trump but of Fidel Castro, from a December 1961 report commissioned by the CIA. Given his politics, you’d think Castro would have little in common with Trump. Yet, even though the language of diagnosis has changed, there are many echoes in the warning put forth by twenty-seven psychiatrists and mental health experts, plus an epilogue by Noam Chomsky in the recent book, The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump.

The book has its origins in a conference held on April 20, 2017, organized by a forensic psychiatrist at the Yale School of Medicine named Bandy X. Lee, in defiance of what some psychiatrists have called a “gag order” issued a month earlier by their professional body, the American Psychiatric Association, which ruled against clinical opinion being given on public figures, even in the interests of national security. Though few psychiatrists attended the conference in person, there was a large following online and the articles initially submitted for the book far exceeded the number included. When the book, edited by Lee, came out in September, headlines and articles appeared in the US and abroad discussing Trump’s dangerousness and “mental impairment.”

The controversy was recently reanimated by a letter sent by Lee on behalf of the books’ contributors to The New York Times, calling for “the public and the lawmakers of this country to push for an urgent evaluation of the president, for which we are in the process of developing a separate but independent expert panel, capable of meeting and carrying out all medical standards of care.” And with the release last week of journalist Michael Wolff’s damning portrait of Trump as a paranoid child-man utterly ill-equipped for office in his book Fire and Fury, Lee and her colleagues have once again found their concerns widely cited.

Laudable as this call and the resulting volume may be, the psychiatrists can do little more than trumpet danger—unless Twenty-Fifth Amendment proceedings determining the president “unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office” are set in motion. At that point, the vice president or the cabinet or Congress can call for a full mental health test and diagnostic assessment. But even then, as the checkered history of psychiatry makes clear, mind professionals don’t always agree with one another, whether on diagnoses or on the dangerousness of a subject. Norms and what we designate as normality also change: women used to be institutionalized for behavior that society and the doctors now think utterly ordinary. The irony of Trump now suggesting that his former chief strategist Steve Bannon “has lost his mind” is evident.

Freud advised against “wild” analysis—the long-distance diagnosis of people who had never lain on a couch—though on occasion he indulged in it. His case studies of Leonardo and Dostoevsky were the result. Both were dead, as was the single politician he turned his gaze on, Woodrow Wilson. That case arose out of conversations with Ambassador William C. Bullitt, briefly an analysand, and ended up as an introduction to Bullitt’s disappointing book on the twenty-eighth president.

In his writings on group psychology and identification, Freud had indicated ways in which the leap from the individual psyche to the social and political sphere might be conceived. The mass killings of the Great War were arguably responsible for propelling him to add an aggressive death instinct to the pleasure principle. Yet he never speculated directly about the rise of Nazism or Hitler’s psychological make-up. Ambassador Bullitt did—as did many others—and wrote warning missives to Roosevelt. Psychoanalytic ideas held enough sway for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) to commission a secret study of Hitler by the psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Walter Langer. Other psychological reports probed the mentality of the German people. Insight into the unconscious mind of the enemy was, as Daniel Pick has shown in The Pursuit of the Nazi Mind (2012), part of the American war effort: even psychoanalytically informed members of the Frankfurt School, such as Herbert Marcuse, contributed to this governmental work by attempting to predict Hitler’s acts and find non-military ways of defeating him and his hold on Germany.

Advertisement

Together with the many materials he gathered, Langer’s classified psychobiography shows a Hitler who is not quite “normal,” a man of demonic will, highly skilled at remaining opaque while able to arouse a mixture of passionate adulation and anger in his audiences and followers. He is a man of confused sexuality who unconsciously identifies with his trampled mother and the sadistic man who brutalized her; he follows his inner voice and can’t tolerate its being thwarted. He is dangerous. By the time World War II had broken out, if not well before, you hardly needed a degree in psychiatry to notice all of this.

The OSS clinicians played a part in the Nuremberg Trials, too, interviewing the Nazi war criminals and supplying material to the prosecutors. So, there is a precedent for psychiatric and psychoanalytic professionals engaging in matters of state in the US. Robert Jay Lifton, the great doyen of psychiatry and psychobiography who provides a foreword for The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump, has written brilliant studies of “brainwashing” among American POWs during the Korean War, and on Hiroshima survivors. His book on the Auschwitz doctors introduced concepts such as the adaptation to, and normalization of, evil. This last provides the strongest underlying argument for the current book’s existence: in certain situations, it is incumbent upon professionals to drop their code of political neutrality and use their authority and expertise to warn of present danger so as to prevent what Lifton calls a “malignant normality” from taking hold. The fear is that, after less than a year of America under Trump, this has already happened.

The trouble is that the mind professionals often disagree with one another—not only on the specificity of diagnosis, but on a host of other matters. Only one presidency ago—as the leading psychiatrists Judith Herman and Bandy X. Lee underline in their prologue— the professional organizations fell out. In 2005, at the height of Bush’s War on Terror, when disputes about the treatment of prisoners in Guantánamo Bay were at their height, the American Psychological Association “rewrote its ethical guidelines to give legal cover to a secret government program of coercive interrogation and to excuse military psychologists who designed and implemented methods of torture.” Meanwhile, the other APA, the American Psychiatric Association, refused to sanction torture and coercive interrogation.

On top of that, the Goldwater Rule—brought into force in 1973 after the 1964 Republican candidate Barry Goldwater won a libel suit against a magazine that had published a survey of psychiatrists’ damaging views of him—made it unethical, and potentially very expensive, for psychiatrists to engage in long-distance diagnosis. The Tarasoff case of 1976, however, made it a duty for professionals to break patient confidentiality and alert authorities and the public if a patient posed an evident threat. While in treatment, a disturbed student at the University of California had murdered Tatiana Tarasoff, a woman who didn’t return his love. The professional who was seeing him had, in fact, warned the campus police of his dangerousness, but the police team had found him “rational.” Insanity, certainly criminal insanity, is neither always readily visible, nor easy to prove in courts of law.

In Trump’s case, the twenty-seven campaigners see the duty to warn of danger as overriding the Goldwater Rule. Each has a variety of diagnostic categories for Trump, but they don’t tell us much more than what savvy lay commentators have often repeated. We learn that Trump is “mentally unstable,” that he exhibits, according to psychologist Philip Zimbardo and counselor Rosemary Sword, “extreme present hedonism” and “lives in the present moment without much thought of any consequences of [his] actions or of the future.” He is impulsive, dehumanizes others and will do whatever it takes to bolster his ego. He also exhibits “malignant narcissism,” which includes antisocial behavior and aspects of paranoia; and “pathological narcissism,” which begins, according to Craig Malkin, “when people become so addicted to feeling special that, just like with any drug, they’ll do anything to get their ‘high,’ including lie, steal, cheat, betray, and even hurt those closest to them.”

Diane Jhueck, who works both in legal and mental health fields, stresses that “mental illness in a US president is not necessarily something that is dangerous for the citizenry he or she governs.” According to a study of the thirty-seven US presidents up to 1974, nearly half “met criteria that suggested psychiatric disorders.” Including personality disorders—beyond the older roll call of bipolar, anxiety and depressive states—would raise the figure to 50 percent or more. If one brings the study towards the present and adds Nixon’s alcoholism, Reagan’s dementia, Bush’s purported sadism, not all that many presidents altogether escape. When compared to Freud’s day or even that of the first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 1952, the number of available psychiatric diagnoses has risen so greatly that it would be pretty easy to find a fit for practically any member of the population.

Advertisement

What distinguishes Trump from the rest of the population, though, is the substantial effect of his personality. His “impulsive blame-shifting, claims of unearned superiority, and delusional levels of grandiosity,” his “unhinged response to court decisions, driven as they appear to be by paranoia, delusion, and a sense of entitlement are of grave concern,” writes Jhueck, and have already impacted on the lives of many. As Hillary Clinton remarked, “A man you can bait with a tweet is not a man we can trust with nuclear weapons.”

Sadly, the misuse of power is not a free-standing psychiatric category, though power seems to exacerbate a whole range of existing “craziness,” whether it is that of movie moguls or politicians.

Trump is more likely to be forced out of office by a loss in the next presidential election than he is by a congressional decision to institute, under Section 4 of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment, “an independent nonpartisan panel of mental health and medical experts to evaluate Mr. Trump’s capability to fulfill the responsibilities of the presidency,” as the book’s authors call for. For that first option, an electoral majority would have to agree that Trump was unsuitable for public office, whether because of his personality disorders or his acts, or both. But the manic qualities he displays—so common in celebrity culture and for so long the signals of Wall Street success—let alone his millions, all seem to be vote-gathering attributes. In the end, what will guard against the president’s excesses and remove him from office is more likely to be politics than the mind doctors—though their campaigning may nudge the politics.

Let us hope that the institutions of democracy allow Trump only three more years, rather than the fifty or so Castro had in power.