Full disclosure: My personal experience of “Age of Terror: Art since 9/11,” the recently-opened exhibition at London’s Imperial War Museum, was informed by the fact that, not thirty-six hours before, a stretch of the Lower Manhattan bike path that, a few blocks from where the World Trade Center stood, is part of my daily routine was the site of a truck attack that killed eight people and injured eleven others. I was out of the country when it occurred, as I had been on September 11, and was overwhelmed with the same desire to see my neighborhood. So, I spent a good half-hour with the video piece installed at the exhibition entrance: Tony Oursler’s Nine Eleven.

As unpretentious as a home movie (which, in a sense, it is), Nine Eleven induced a weird sort of nostalgia. Oursler began filming after the tower was hit, but what I found equally compelling was the material that followed. Nine Eleven recalled to mind much that I had forgotten about the immediate aftermath of September 11 in what had been the World Trade Center’s immediate vicinity—the hand-captioned posted pictures of the missing, the twisted wreckage of the building façade (so emblematic that it should have remained a memorial like the bombed-out church in central Berlin), the pile of rubble that smoldered for weeks, the fact that Oursler was only one of many who were taking pictures at Ground Zero.

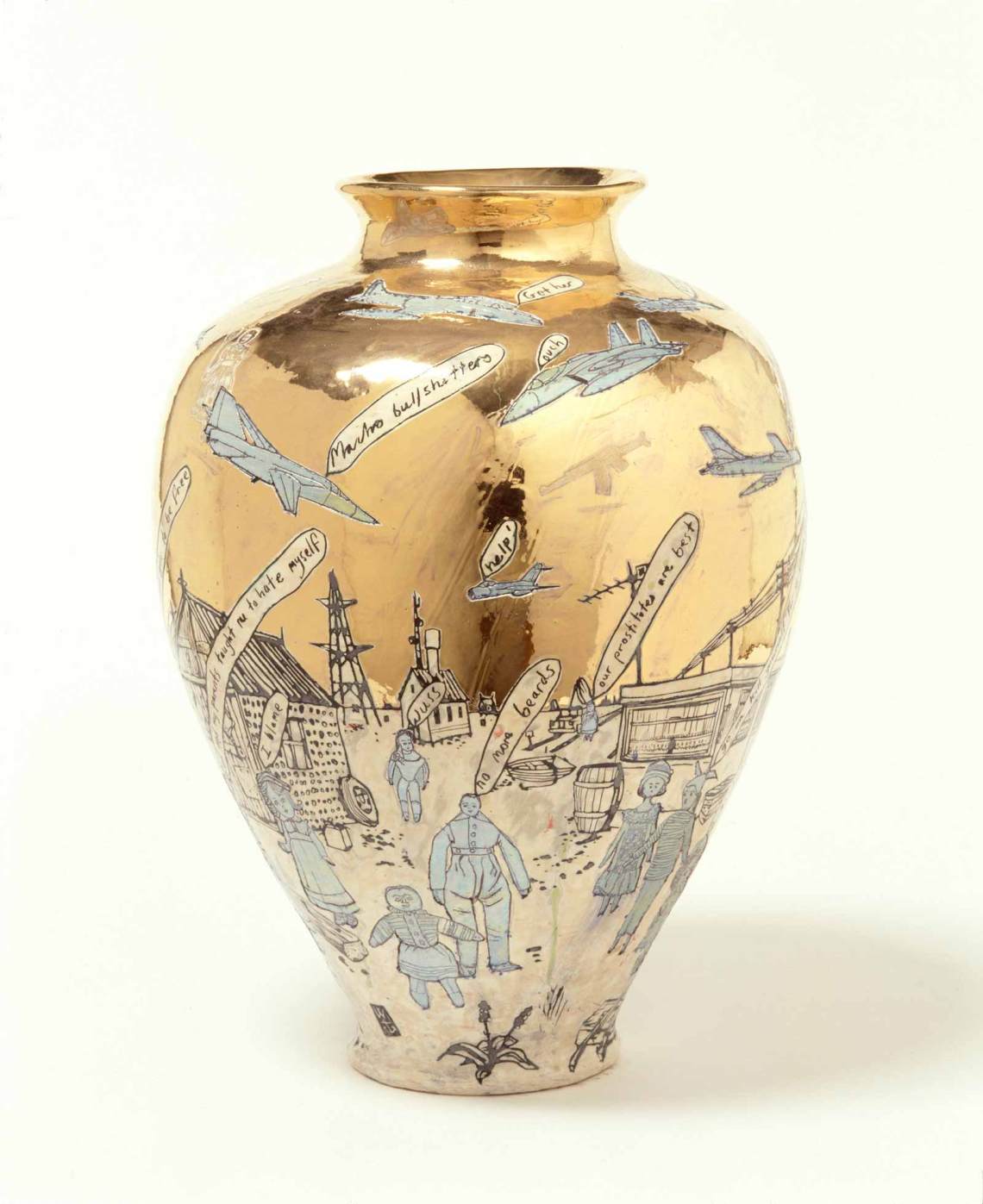

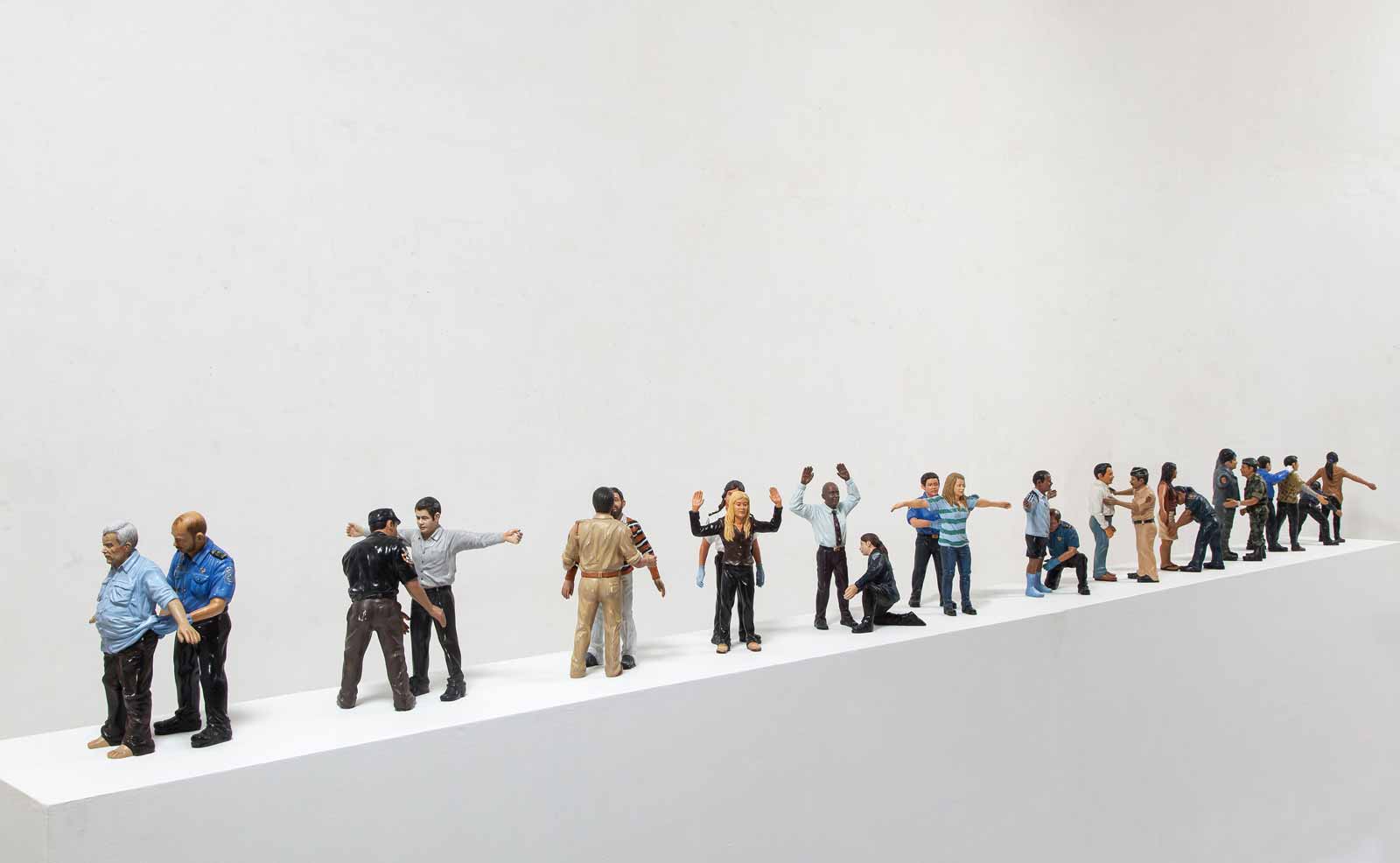

The IWM show, which is the largest of contemporary art in the museum’s history, is divided into four sections (titled “9/11,” “State Control,” “Weapons,” and “Home”). Among the exhibits are a fair number of common, albeit modified, objects: a breakfront stocked with mirrored hand grenades, a series of mock Dresden figurines undergoing various types of body search, and an Afghan rug featuring a drone (of three such “war rugs” commissioned by European artists). The busiest, least disturbing of these artifacts is the ceramicist Grayson Perry’s gold, reflective urn embellished with bombers, burning buildings, baby dolls, and obscenities.

“Age of Terror” is also filled with pieces designed to be experienced over time. These include some confrontational, but otherwise unremarkable, video installations concerning torture and drone pilots by Coco Fusco and Omar Fast, and the truly remarkable Bomb Iraq, a homemade video game apparently created in the mid-1990s that the mixed-media artist Cory Arcangel discovered on a used computer purchased in a thrift store.

Much of Oursler’s Nine Eleven, however, is powerfully mundane. More evocative than the presence of the army in the streets in the days after September 11 were the religious fanatics and Good Samaritans who arrived from all over America, as well as the merchandizers and the nuts who gave the scene the teeming quality of a medieval marketplace. This aftermath is the subject of the show. One goes from Nine Eleven to Hans-Peter Feldmann’s 9/12 Frontpage—a full wall of the following day’s newspaper coverage from across the globe. A particularly resonant video piece documentes the performance artist Fabian Knecht’s peregrinations through Lower Manhattan dressed in an ash-covered suit, attracting so little notice that he might have been invisible. (Going from Lower Manhattan to midtown in the days after the attack was truly entering another world, a journey that required one to show a passport on return.)

For the most part, “Age of Terror” is sobering, serious stuff. Still, the British press does not seem to have been especially impressed. More than one review has criticized the show and even its premise as trite or banal. Some have argued that art is simply unequal to the magnitude of the event. But isn’t that a given? Who can forget Karlheinz Stockhausen’s shocking observation, six days after the Twin Towers fell, that the attack was “the greatest work of art imaginable for the whole cosmos”?

Steven Spielberg tried hard to represent the cataclysm in the opening scenes of his War of the Worlds, a movie he described as, in some sense, a documentary. But artists cannot recreate September 11, only respond to it. Gerhard Richter and Sabine Moritz were together on a New York-bound plane when the towers went down and felt compelled to make paintings addressing the event, not unlike the Post-It notes that, as shown in Oursler’s video, spontaneously appeared in public spaces throughout Manhattan in the days following the attack, expressing grief or declaring solidarity. (A similar thing happened, on a smaller scale, on the morning after Trump’s election.)

Advertisement

The most blatant, as well as the blandest, bid for an “Age of Terror icon” is Ai Weiwei’s white marble Surveillance Camera with Plinth. The piece is brutal but not melodramatic. Like the show’s various war rugs or Arcangel’s found computer game or Knecht’s performance piece, Ai’s mini-monument recognizes the fact of ordinary terror, terror as routine.

Given that the exhibition’s strongest pieces evoke a regime of terror (rather than the Age), I was surprised that there was nothing here by Laura Poitras, whose 2016 Whitney show, “Astro Noise,” was devoted to what might be called the post-September 11 global village. But I was gratified to see that “Age of Terror” ends with a section largely devoted to artists born in present-day war zones: Lida Abdul (Afghanistan), Khaled Abdul Wahed (Syria), Hanaa Malallah (Iraq), Jamal Penjweny, and Walid Siti (both Iraqi Kurdistan). Their modest pieces featuring deranged maps, photographs or models of wrecked homes, and other exercises in extreme dislocation give testimony to the way they—dare we say, “we?”—live now, a bomb or a bike path from oblivion.

“Age of Terror: Art since 9/11” is on view at the Imperial War Museum through May 28, 2018.