On January 11, on a sweltering summer afternoon in Cape Town, J.M. Coetzee gave a rare public reading in the home town he left, somewhat precipitously, fifteen years ago to take up an academic post in Adelaide, South Australia. The reading took place at the Irma Stern Museum in the city’s southern suburbs, currently hosting an exhibition of arresting Coetzee juvenilia: “Photographs from Boyhood,” a recently discovered trove that the author took in the mid-Fifties when he was a schoolboy growing up in these suburbs. In his wry and unsparing way, Coetzee projected a series of these images onto a screen and read related extracts from his 1997 fictionalized memoir Boyhood (he calls the genre “autre-biography,” because it always involves making an artifact of one’s life for an “other”).

In Boyhood and its sequels, Youth and Summertime, Coetzee uses family photographs as aides-memoire but makes no mention of his own adolescent passion for taking them. How fascinating it was, then, to see the images made in boyhood in dialogue with the words of an older man looking back, and to imagine the way the ethics and aesthetics of the former might have forged the latter; also, to consider what the image reveals that the word cannot, and vice-versa.

The author himself was no help. “It’s not my job to join up the dots,” he says, at the conclusion of an interview published on the occasion of the exhibition, which is curated by Hermann Wittenberg and Farzanah Badsha. He ended his presentation at the Irma Stern Museum at precisely thirty minutes, leaving no room for questions and an audience hankering—as happens with Coetzee—for more.

Before J.M. Coetzee was the writer who would go on to win the Booker and Nobel Prizes, he was an avid photographer: the home darkroom he set up is reconstructed in the exhibition, with its original machinery and empty canisters, and some records from his school photography club are on display. These reveal that although his entries placed second and third in a competition, he scored poorly for “neatness and general work”: eight out of twenty-five and four out of twenty-five, respectively, for his two entries. This is no surprise to anyone acquainted with the talented, disaffected anti-hero of Boyhood.

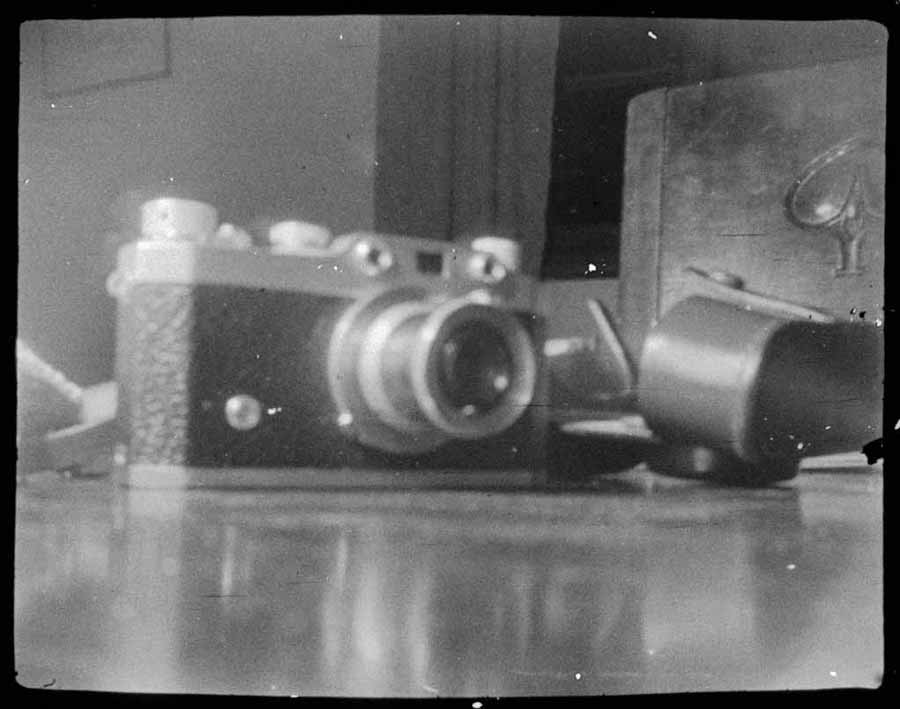

Coetzee was the owner, first, of a mail-order “spy camera” and then of a 35 mm Wega, an Italian Leica knockoff. He snuck shots of his mother sleeping and the cassocked masters at his Catholic school; he photographed hijinks in the classroom and events on the sportsfield, the people and the landscapes of his adolescence. He liked to document his own working process—as a reader, as a photographer, as a thinker, as a cricketer even—and one of the exhibition’s gifts is an itemized photograph of the library that the sixteen-year-old Coetzee created with his pocket money. “Some of these books left a mark on me,” he writes in the caption. “Eliot’s poems, War and Peace. Others I never succeeded in wading through: The Imitation of Christ. Self-improvement via Everyman’s Library and the Penguin Classics.”

Like the protagonist of Boyhood, the boy-photographer is self-conscious and earnest, although the tentative smile in one of a quartet of proto-selfies (taken with a timer or a clicker) suggests a willingness to please that is absent from the book or the author’s later public image. “Who is this person?” the adult Coetzee asks of these images of his younger self, in the accompanying caption. “First steps towards surprising and uncovering his soul.” It is as if the adult author is giving us a clue to his creativity: that his work ever since has been an endeavor to “surprise” and to “uncover” his soul.

What does it mean to surprise a soul? Most of the images are unplanned and spontaneous, in the manner of Cartier-Bresson, whom Coetzee imitated, as he says, in his attempt to be “present at the moment when truth revealed itself, a moment which one half discovered but also half created.” The young photographer is trying to surprise his subjects by catching them unawares, but also, one senses, to surprise himself with a fearlessness that is lacking in the written account of his boyhood. He was attracted to photography because it carried “considerable cultural cachet” in the Fifties, but also, he says, because it was “a manly activity, in contrast to such effeminate activities as composing poetry or playing the piano.”

Advertisement

Interestingly, the other photographer in Coetzee’s family—there is an image of her with her own box-brownie—was his mother, Vera, whose excessive solicitousness he describes with cool contempt in Boyhood. His feckless father, Jack, is captured being hectored by his mother’s Aunt Annie, and Coetzee gives us a passage from Boyhood as the caption: “He has never worked out the position of his father in the household. In fact, it is not obvious to him by what right his father is there at all.”

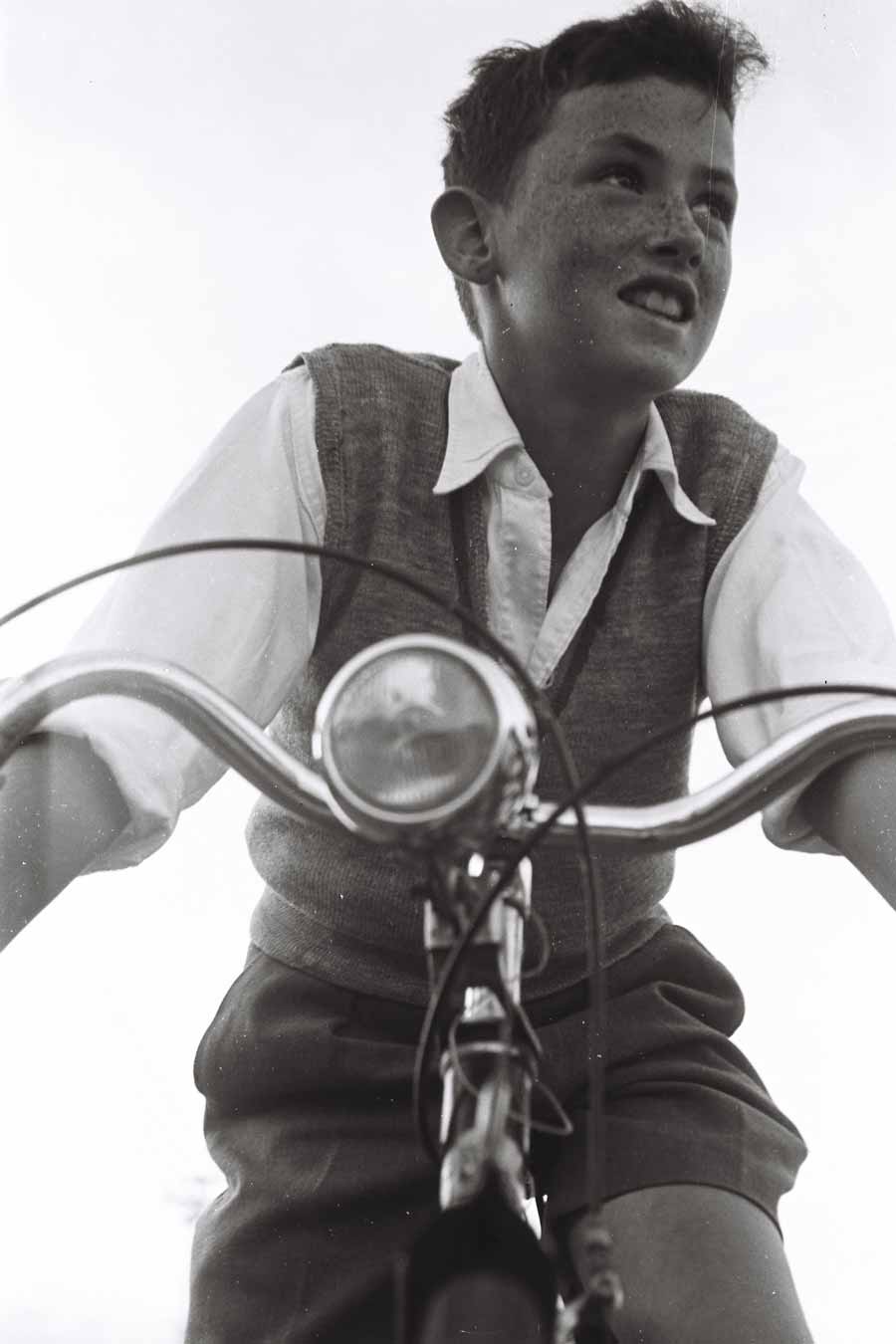

In Boyhood, he is similarly cool about his younger brother David, who is “at most a nervous, wishy-washy imitation” of the book’s protagonist. But one of the most beautiful images in the exhibition is of David riding a bicycle, very much à la Cartier-Bresson. The image was a technical experiment in low angles and shutter speed, but it seems to capture both a moment of the younger brother’s childish joy and an older brother’s capacity for empathy, despite the author of Boyhood’s later protestations to the contrary. Perhaps this is fanciful. And I wonder whether we, the viewers, are not projecting our need to humanize one of the world’s greatest authors if we find such empathy in the many images of his mother, stout in middle age by the time her son took up the camera, vulnerable rather than doughty.

In an early essay of his titled “Photographs of South Africa,” Coetzee warns us not to read old photographs this way, and he questions whether “looks have the power to communicate feelings,” chiding the white editors of a book of nineteenth-century South African photographs for interpreting the look of a black girl selling brooms as “wistful.” He concedes that “this is by no means to argue that all faces from the past must be as inscrutable as the faces of Martians,” but anyone who has read Coetzee’s fiction will know the stock he puts in inscrutability—his own and that of his characters. It is precisely in his refusal of easy empathy that he has forged the counter-intuitive ethic of his work, and we might find the roots of this in the true marvel of the exhibition: the few images he made of black South Africans, which have a sense of drama, of “surprise” and of “uncovering,” that is absent elsewhere in his photographs.

In some respects, these images suggest the path that Coetzee might have taken—in a venerable South African tradition—as a social documentarian like, for example, David Goldblatt. The quick image Coetzee captures of a policeman stopping black workers on a suburban “Paradise Road” finds its punctum in the quiet resistance of a uniformed maid’s folded arms. And there are fluid, free-wheeling images of the workers on the beloved Coetzee family farm, deep in the hinterland, which he visited every Christmas. When one looks at the image of a white child weaving easily between farmhands aiming guns and cleaning offal, one is struck by how a photograph can suggest correspondences and relationships in a manner quite different from the written word.

The critic Maya Jaggi noted in the Financial Times that “the unexpected intimacy” of these images “appears to flout the spirit of rules that came to my mind from Boyhood”: the protagonist averting his eyes when passing a “colored” maid in the passage; his mother contemplating smashing a teacup after a “colored” man has drunk from it. (In South Africa, “colored” was the apartheid designation for people of mixed race, or descendants of the Khoisan people.) Coetzee’s photographs of these people—in service to him and his family, to be sure—suggest the way the rigid lines of racial separation can be crossed with a camera; or the way, perhaps, that the camera can expose the arbitrariness of such boundaries.

But the camera is also a tool of immense power, particularly in southern Africa, where photographs were used to classify people in colonial times and then to control them: your passbook photo was a ticket to work, or to jail, depending on whether it had been endorsed. By day, the protagonist of Boyhood must avert his eyes when passing the maid in the passage, but at night, the photographer of “Photographs from Boyhood” can watch her, freely, as she dances the “tiekiedraai” (an Afrikaans folkdance) on New Year’s Eve. The Wega in his hand not only gives him permission: it renders visible the power his society actually vests in him. He can choose whether to look, or not, with or without the consent of the people he is looking at. In a white world so blinkered by apartheid, though, the wonder of these images is that this particular young man chose to look at all.

Advertisement

And yet, Coetzee tells us in his exhibition interview, such a project was not to his liking. He gave up photography, he says, because of a lack of empathy and curiosity: “I was never open enough to the world, particularly to other people’s experience. I was too wrapped up in myself. Which is not unusual at that age.”

In what measure was it adolescence that stifled his curiosity, and in what measure was it apartheid? At the Irma Stern Museum, while projecting a photograph of two of the farm laborers, Coetzee read the following passage about the men from Boyhood:

He burns with curiosity about the lives they live. Do they wear vests and underpants like white people? Do they each have a bed? Do they sleep naked or in their work clothes or do they have pyjamas? Do they eat proper meals, sitting at table with knives and forks?

He has no way of answering these questions, for he is discouraged from visiting their houses. It would be rude, he is told—rude because Ros and Freek would find it embarrassing.

The young photographer does not transgress this boundary with his camera, he tells us in Boyhood, because this was a limit to which he also adhered. But one must take Coetzee’s protestations of a later lack of curiosity with a pinch of salt, for one senses, looking at some these images, that he came to understand the way storytelling was driven by not being allowed across a threshold, by turning in on oneself and imagining what might lurk beyond it.

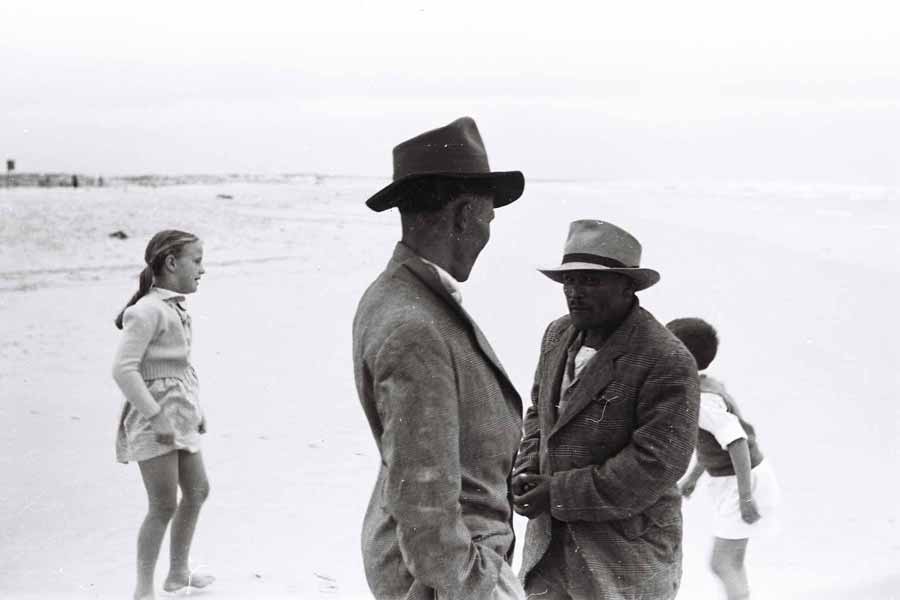

And so, in “Photographs from Boyhood” he gives us Ros and Freek, in an arresting sequence “on Strandfontein beach—their first ever sight of the sea.” The images conjure Waiting for Godot (which Coetzee would not yet, by then, have read), a Giacometti sculpture, a Steinbeck story. Here we have, at last, Coetzee the novelist rather than the documentarian, and there is glory in the way these images make fiction: the uneasy presence of two dark beings etched into the blanched landscape of sand and sea; the questions that cannot be answered. Ros and Freek lived and worked on a farm in the Karoo region, hundreds of miles away. How did they get to Cape Town, to the sea, these two middle-aged men in their ill-fitting Sunday suits, trying to light their pipes in a south-easterly gale? And what was Coetzee doing there, with them? His caption: “What they thought of it, I will never know.”

“Photographs from Boyhood” is at the Irma Stern Museum, Cape Town, until January 20. It will open at the J.M. Coetzee Center for Creative Practice at the University of Adelaide, South Australia, in September.