The first time I read George Schuyler’s 1931 novel, Black No More, it confused and unsettled me. Black No More is based on a fantastical, speculative premise: What if there were a machine that could turn black people permanently white? What if such a machine were invented in and introduced to 1920s America, a time of both increasing racial pride and persistent racial violence? What would the social and political implications be of such a race-reversal machine? What would it reveal about society? What lies and hypocrisies about blackness and whiteness and American identity would be revealed by the chaos that would ensue?

I was in college at the time I first read the book, and not quite ready for its cynical, almost misanthropic vision of race and society.

I had just reached that stage of racial identity that psychologist William Cross, in his 1971 “Negro-to-Black Conversion Experience,” called “immersion.” The immersion stage (number three of five) is when you eat, drink, and excrete blackness. It’s when you bite off the head of anybody who questions whether you, no matter how high your yellow, are anything less than Afrika Bambaataa.

What unsettled me about Black No More wasn’t just what I knew of Schuyler’s vaguely messed-up politics (which became a whole lot less vague and a whole lot more messed up in the decades following the novel’s publication). It was also that Schuyler was so merciless—about everyone. At the exact moment I was finding power and purpose in my black identity, he was telling me race didn’t exist.

His stance was familiar to me. The truth was, he reminded me of my father, another black intellectual who was prone to making fun of everyone. It was my father who taught me how to laugh at race. As a child, I had already noticed that the discussion of race in white liberal America was always and only a discussion of blackness, never whiteness. In that space of earnestness, blackness became either magical or noble or tragic or essentially wicked. But in the black space of my father’s home, race was a far more multilayered conversation. Whiteness was named. Nothing was sacrosanct.

It was my father who told me the first racist jokes I’d ever heard—jokes written by white people at our expense. My father never laughed so hard as he did at those punch lines. Looking back, I think he was trying to teach me the art of black satire—showing me how to find the joke about whiteness hidden within a joke about blackness. I learned from my father how horror could become humor and all the ways humor could be horrifying. What I recognized in reading Black No More was a similar sense of the black absurd. But I was in college, three thousand miles from my original home and newly adrift, searching for a place to call home. Schuyler thumbed his nose at the very things I was trying to hold sacred.

I squirmed most while reading the chapter in which Schuyler takes down all those Black History Month heroes, especially his lampoon of Marcus Garvey. At eight years old I briefly attended an experimental Afrocentric school based on Garvey’s teachings—a miserable experience—but still, I wasn’t ready for Schuyler’s wicked rendering of the Garveyesque figure he renames Santop Licorice. Mr. Santop Licorice, Schuyler writes, had “for some fifteen years… been very profitably advocating the emigration of all the American Negroes to Africa. He had not, of course, gone there himself and had not the slightest intention of going so far from the fleshpots, but he told the other Negroes to go.” Schuyler demonstrates here, and throughout the novel, an awareness of the class politics of racial consciousness, writing of the way racial identity politics, like anything else, can become part of the capitalist production wheel:

Naturally the first step in their going [back to Africa] was to join [Licorice’s] society by paying five dollars a year for membership, ten dollars for a gold, green and purple robe and silver-colored helmet that together cost two dollars and a half, contributing five dollars to the Santop Licorice Defense Fund (there was a perpetual defense fund because Licorice was perpetually in the courts for fraud of some kind).… [Licorice attempted] to save the Negroes by vicariously attacking all of the other Negro organizations and at the same time preaching racial solidarity and cooperation in his weekly newspaper, “The African Abroad,” which was printed by white folks and had until a year ago been full of skin-whitening and hair-straightening advertisements.

Schuyler doesn’t stop with Garvey. He pokes fun at James Weldon Johnson, the high-yellow Harlem Renaissance raceman who wrote that classic of tragic mulatto literature, The Autobiography of an Ex–Colored Man—and also wrote that song “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” otherwise known as the black national anthem, which I sang in a quavering voice every week with my fellow Black Student Union members to close out our meetings.

Advertisement

Schuyler’s most intense vitriol, however, is reserved for W.E.B. Du Bois, who can easily be recognized in the character of Dr. Shakespeare Agamemnon Beard, founder of the National Social Equality League. “For a mere six thousand dollars a year,” Schuyler writes of Beard,

the learned doctor wrote scholarly and biting editorials in The Dilemma denouncing the Caucasians whom he secretly admired and lauding the greatness of the Negroes whom he alternately pitied and despised. In limpid prose he told of the sufferings and privations of the downtrodden black workers with whose lives he was totally and thankfully unfamiliar. Like most Negro leaders, he deified the black woman but abstained from employing aught save octoroons. He talked at white banquets about “we of the black race” and admitted in books that he was part-French, part-Russian, part-Indian and part-Negro.… In a real way, he loved his people.

*

The protagonist of Black No More, Max Disher, has no moral center: he is willing to do anything for personal gain. He is a black man who is so hungry for all that white America has withheld from him that when given the opportunity to turn white, he jumps at the chance to go in the Black-Off machine (a precursor to Dr. Seuss’s Star-Off Machine in The Sneetches)—as does all of Harlem. They want access to everything that whiteness will afford them: money, freedom, mobility, and power. Like Eddie Murphy in that famous 1980s SNL skit “White Like Me,” where he dons white pancake makeup and a straight-haired blond wig and goes undercover to discover that white privilege is much worse than he thought, Schuyler’s character discovers what he can get in the American marketplace when he is cloaked in a skin tone and bone structure and hair that are read as white. No other novel I’ve read before or since so baldly exposes whiteness as a valuable commodity.

In the Black-Off machine, Max Disher transforms into Matt Fisher, a white anthropologist. A novel about a black man becomes a novel about a white man who was black once upon a time. And yet while passing into white America, Max-turned-Matt consistently finds only disappointment in the so-called superior race. He mourns his lost blackness, and in doing so reveals the fallacy of white supremacy:

As a boy he had been taught to look up to white folks as just a little less than gods. Now he found them little different from the Negroes, except that they were uniformly less courteous and less interesting.… Often when the desire for the happy-go-lucky, jovial good fellowship of the Negroes came upon him strongly, he would go down to Auburn Avenue and stroll around the vicinity, looking at the dark folk and listening to their conversation and banter. But no one down there wanted him around. He was a white man and thus suspect.… There was nothing left for him except the hard, materialistic, grasping, ill-bred society of the whites. Sometimes a slight feeling of regret that he had left his people forever would cross his mind, but it fled before the painful memories of past experiences in this, his home town.

Schuyler argued in one of his earlier writings, a 1926 editorial for the Pittsburgh Courier, that the roots of white racism were a fear of black superiority. “Whites realize that given free rein, the Negro would very likely be running the country in less than half a century.… The average white man of sense knows the average Negro is his equal and very often his superior; that is the reason why he limits the Negro’s sphere of activity.”

Black No More argues compellingly, provocatively, that the idea of blackness is necessary in order for whiteness to survive. It is much like James Baldwin famously said: “What white people have to do is try and find out in their own hearts why it was necessary to have a nigger in the first place, because I’m not a nigger. I’m a man, but if you think I’m a nigger, it means you need it.… If I’m not a nigger and you invented him—you, the white people, invented him—then you’ve got to find out why. And the future of the country depends on that, whether or not it’s able to ask that question.”

Schuyler shows all the ways white people are lost without black people to define themselves against. In one late, amazing scene in Black No More, the pastor of a failing white church in the South is grieving the loss of black people after they’ve all turned white. He is grieving the fact that there is nobody left for him to lynch—and without black bodies to lynch, the white parishioners will never know the pastor’s true greatness.

Advertisement

Schuyler dedicated Black No More to “all Caucasians in the great republic who can trace their ancestry back ten generations and confidently assert that there are no Black leaves, twigs, limbs or branches on their family trees.” Before it had been confirmed by social scientists, he understood that there was no such thing as race as a real, biologically determined category. But he saw how real race’s influence was, and all the ways racialized thinking—that other opiate of the masses—limited and imprisoned both black and white Americans.

In Black No More, racialized thinking has turned white people into nothing but self-satisfied buffoons. The white workers are so distracted by their hatred of black people that they will never see the true source of their oppression, the white wealthy landowners who exploit their labor. Black leaders are portrayed as corrupt—especially the high-yellow octoroons being paid a fortune to speak for the larger race, to whom they feel distant and superior. In one scathing passage Schuyler writes: “While a large staff of officials was eager to end all oppression and persecution of the Negro, they were never so happy and excited as when a Negro was barred from a theater or fried to a crisp.” The black and white working classes are shown to be victims of an elite of white supremacists and black racemen who use race as a tool to deflect attention from their own greed.

At a moment when black writers were finally awakening to the beauty of black culture, Schuyler had moved on to the part where we deconstruct race. He showed neither sentimentality nor chauvinism for his own race or any other. He hated everyone, and there is a strange purity to his loathing, a kind of beauty to his cynicism. It is his resistance to pandering, to joining tribes and clubs that feels so refreshing. It is the loneliness of Schuyler’s position that makes me trust it.

*

Long before Schuyler published Black No More, the seeds of his anti-authority iconoclasm and his impulse toward Swiftian satire had been planted. He was already disillusioned with every club he had ever flirted with joining.

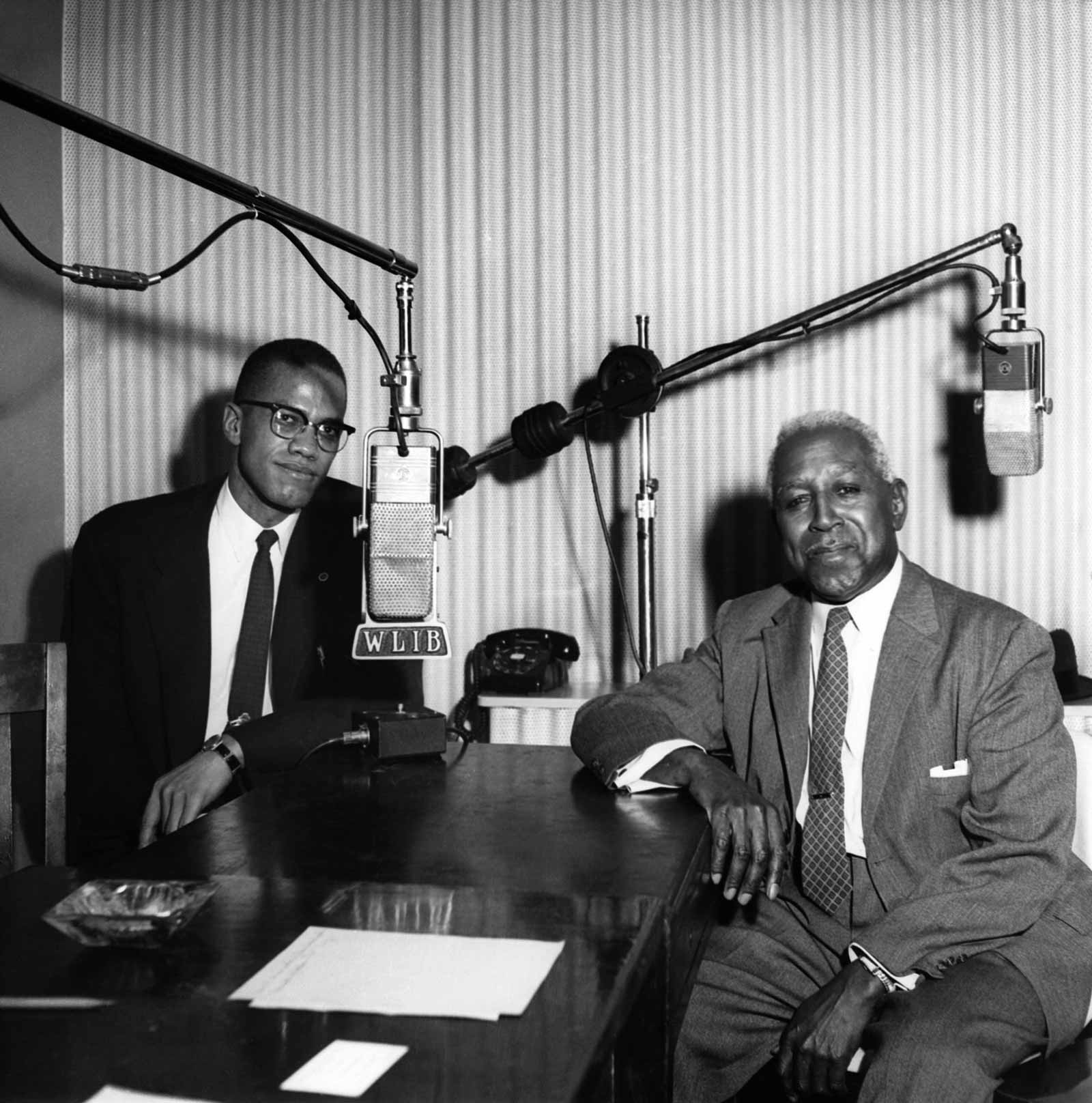

Schuyler had joined the military as a young, working-class black man and had risen to become a lieutenant, but he defected after a series of racist incidents. Sometime later he arrived in New York City and lived a kind of hobo rogue intellectual life, staying for a time in the Phyllis Wheatley Hotel, owned by Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Society—a group he considered joining but whose corruption left a bad taste. He read voraciously all things socialist, and by 1923 he was an editor and columnist for The Messenger, a magazine owned by the black socialist Friends of Negro Freedom. But he was already branching out, writing for other publications outside the black press. He published a cutting tongue-in-cheek critique of white supremacy for H.L. Menken’s American Mercury. In 1926, at the height of the Harlem Renaissance, when Negro life was finally in vogue and Negro culture and art were beginning to be fetishized by both blacks and whites, he wrote a controversial essay for The Nation called “The Negro-Art Hokum,” in which he criticized romantic primitivism among blacks and whites, famously saying that Negroes were just “lampblacked Anglo-Saxon[s]” and that there was no difference between black and white American culture, only class and geographical differences. A week later Langston Hughes was hired to write a rebuttal; in his essay, “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” he critiqued “this urge within the race toward whiteness, the desire to pour racial individuality into the mold of American standardization, and to be as little Negro and as much American as possible.” Hughes argued for a celebration of a distinctly African American aesthetic.

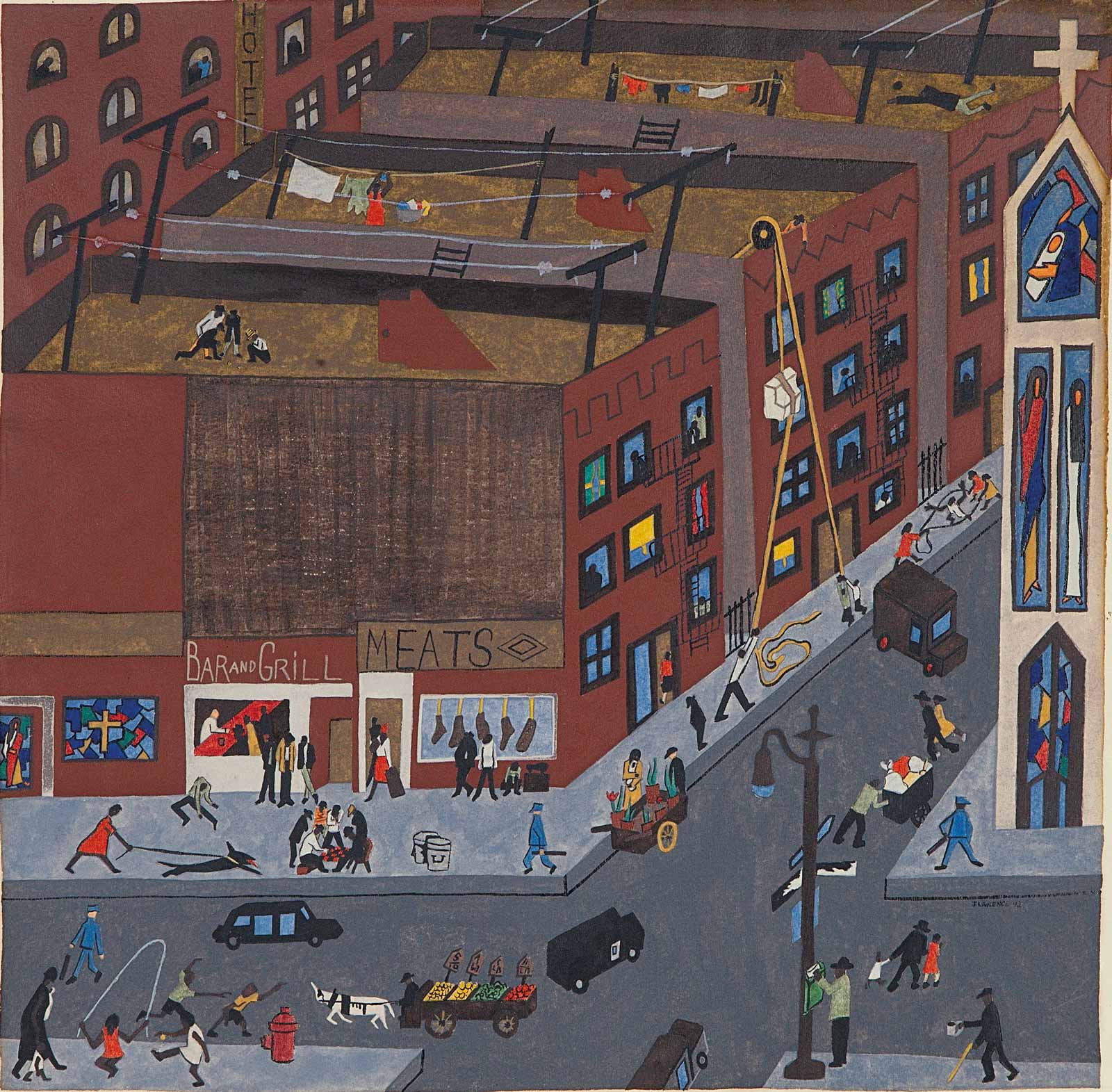

Schuyler’s spirit as an outsider was fully in effect. The historian John Henrik Clarke once said of him, “I used to tell people that George got up in the morning, waited to see which way the world was turning, then struck out in the opposite direction.” Being a consummate outsider, by force and by choice, left Schuyler free to parody everyone. At the root of his position as a satirist was his cultural homelessness. Though he’d come from working-class roots, he was too well read, well traveled, and successful as a writer to ever return to them. He had no solid home in the black elite either: He was too dark-skinned, for one thing, and lacked pedigree. He chafed against hero worship, orthodoxy, and the glorification of race, and was fascinated by intergroup racism and classism. He married Josephine, a white Texas socialite turned New York bohemian, and they had a baby girl, Philippa. Schuyler’s small interracial family became his only tribe—the island of the misfit toys. They lived in Harlem, in the well-to-do black neighborhood of Sugar Hill, where Schuyler published his first novel, Slaves Today, which infuriated black America. It was a harsh depiction of Liberia, the oldest black republic in the modern world, founded as a refuge for liberated American slaves. Schuyler depicted the slave trade there as being led by black Africans.

He was a man of contradictions. For someone so utterly unsentimental and sternly rational about race and blackness, he indulged his wife’s strange neoessentialist belief in “hybrid vigor”—that is, her belief that their daughter’s racial fusion of black and white represented the birth of a new, superior race. With Schuyler’s help, his wife turned their only daughter into a social experiment, raising Philippa on a scientifically prepared diet of raw meat, unpasteurized milk, and castor oil, and keeping her in near isolation from other children. The child’s strange upbringing was both a raging success and a terrible failure. Philippa learned to read at two, became an accomplished pianist at four, and a composer by five. She was a child celebrity, a kind of black Shirley Temple with a high IQ who became the subject of scores of articles in publications such as Time, The New York Times, and The New Yorker, and was roundly hailed as a genius. There is a poignant moment in Kathryn Talalay’s biography of Philippa Schuyler, Composition in Black and White, when Philippa is thirteen and her parents finally show her the detailed scrapbook they’ve been keeping about her upbringing and career—notes and articles they’ve been keeping diligently over the years. Philippa, rather than being touched, was horrified to realize, with sudden clarity, all the ways she’d been her parents’ social experiment and “puppet.” In the years that followed, she grew increasingly disillusioned with America, her own blackness, and the musical career of her youth. Like a character out of Black No More, she eventually changed her name and began to pass as white—as an Iberian-American named Filipa Montera. She spent most of her adult life overseas, still playing music, but less seriously, and trying to find herself in various romantic affairs. She eventually tried to reinvent herself as an international journalist and children’s advocate, and in 1967 she died in a helicopter crash while attempting to evacuate war orphans out of Vietnam.

*

In the years that followed the publication of Black No More, Schuyler’s healthy skepticism toward authority and his absurdist, freewheeling humor gave way to rigidity and humorless far-right extremism. In the end he did join a club, the John Birch Society, and became the kind of tool of the far right that he might have brilliantly parodied in his earlier work. The statements he made later in life against the civil rights movement and in particular against Martin Luther King Jr. would taint his public image and allow him to be dismissed as a serious thinker.

The turn against Schuyler can be glimpsed in the 1971 edition of Black No More, in the introduction by Charles Larson, a prominent scholar of African and African American literature. In a scolding, censorious tone, Larson makes it clear how much he dislikes both the novel and its author:

Black No More is disturbing in these days of renewed Black Pride and Black Power. There is no pride in being black and certainly little indication that the black person in America has anything culturally his own worth holding on to.… It is a plea for assimilation, for mediocrity, for reduplication, for faith in the (white) American dream.… Hardly a page passes by without some aspect of black American life being satirized or attacked.… Schuyler’s bitterness is clearly apparent.

Reducing Black No More to the mildly amusing but ultimately unimportant scribblings of a black reactionary, Larson turns a blind eye to all the ways the novel was and remains a liberating and lacerating critique of American racial madness, capitalism, and white superiority.

Rereading Black No More so many years later, in the era of Trump and Rachel Dolezal, Beyoncé’s “Formation” and that radical Pepsi commercial starring Kendall Jenner, of the rise and fall of Tiger Woods’s land of Cablinasia, and of Michael Jackson’s “race lift” and subsequent death, Schuyler’s wild, misanthropic, take-no-prisoners satire of American life seems more relevant than ever.

Schuyler belongs to the pantheon of black writers in America who have seen their work either reviled, forgotten, dismissed, or—most commonly—ignored in their own lifetime. In this respect, he belongs in the company of Chester Himes, Fran Ross, William Melvin Kelley, Zora Neale Hurston, and Nella Larsen, most of whom died in poverty or saw their work go out of print, and whose work was appreciated only after they were gone—and in some cases, not yet.

There is no stable ground to stand on in Black No More. Its irony and merciless satire steadfastly resist the anthropological gaze of the reader. It is a novel in whiteface. And while black literature is almost always read as either autobiography or sociology, Schuyler’s work can be read as neither. It is one of the earliest examples of black speculative fiction. Black No More resists the push toward preaching and the urge toward looking backward into history. Afrofuturist before such a term existed, it insists, instead, on peering forward into what could come to be.

Adapted from Danzy Senna’s introduction to George S. Schuyler’s Black No More, which is reissued by Penguin Classics.