Peter Hujar was a stalwart—if reluctant—presence in the downtown demi-monde of late twentieth-century New York. The East Village, where he lived in the 1970s and 1980s, when he was most productive as an artist, had long been a breeding ground for unorthodox thought, behavior, and creative activity, a place where the spirit of the age bubbled up from the streets. Hujar was well-known in the upper echelons of the avant-garde, a circle of cultural influence that included numerous figures who had crossed into mainstream notoriety: William Burroughs, John Cage, Allen Ginsberg, Fran Lebowitz, Susan Sontag, John Waters, Robert Wilson—all of whom Hujar had photographed.

Hujar’s work and that of his younger contemporary, Robert Mapplethorpe, reflected the radical sexual changes of the 1970s, when the rise of the gay rights movement coincided with the growing stature of photography in the art world. Hujar and Mapplethorpe lived ten blocks apart. They maintained a chilly distance from one another, yet they had much in common: both were gay; both photographed the male nude; and both made portraits, sometimes of the same people. While Mapplethorpe’s photographs are impersonal, suffused with the arctic elegance of a pure formalist, Hujar’s photographs are formally resolved, intimate, and playful. As Mapplethorpe’s reputation grew in the art world, Hujar became dismissive of his work: “Well, it looks like art,” he would scoff.

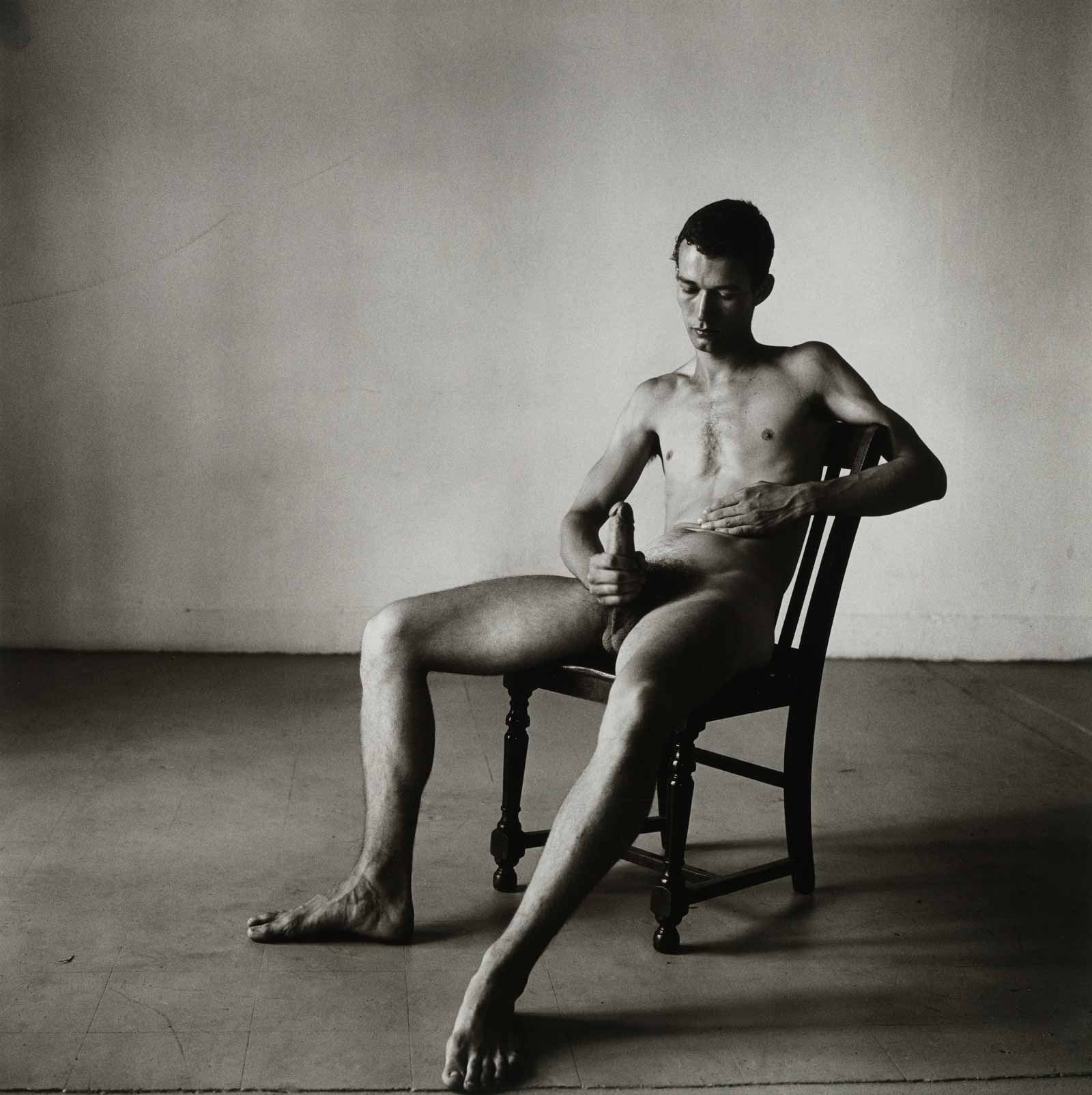

Hujar’s photographic subjects were not specimens of American male perfection; his nude figures were idiosyncratic yet erotic. In one of his signature nude studies, Bruce de Ste. Croix (1976), the subject is seated in a chair, contemplating his erection. This portrait represents Hujar’s conscious attempt to reintroduce male genitalia into Western art, and he was taking it a step further: the erection had never before been photographed with such aesthetic regard.

Hujar met Ste. Croix one night in a neighborhood laundromat in the early 1970s. Ste. Croix, a dancer, had recently moved to New York to work with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company. He would later become the archivist for John Cage. Like so many sexual assignations in the gay world at that time, their brief romance found its way to a more casual friendship, and it would be several years before Peter asked Bruce to pose for the portrait with an erection. Initially, Ste. Croix, who had been brought up Catholic, was scandalized at the prospect; his fellow dancers were convinced it would destroy his career. “I find holy in everything, in the most ordinary of moments, and when I was a dancer I found holy in the human body,” Ste. Croix recalled. Yet, he trusted Hujar and consented. The portrait session took several hours, and for Ste. Croix, Hujar was like a choreographer working with a dancer. Because they were once lovers, Peter was able to coax away his subject’s self-consciousness until Bruce was comfortable enough to arouse himself. “I had been a dancer, and I was used to being an object in other people’s art. So the dance was to be a young man with an erection, and naked.”

In 1978, Hujar was included in a group show called “The Male Nude: A Survey in Photography” at the Marcuse Pfeifer Gallery on Madison Avenue, a few blocks from the Whitney Museum. The male nude was a threatening subject in mid-twentieth century America, a country still bound to a puritanical ethic. In Bruce de Ste. Croix, the view of an erect penis compels spontaneous sexual desire in some, while in others it summons a call to arms against a brandished weapon; either way, the fear—or desire—of being penetrated by so formidable an erotic object seems an unavoidable aspect of the piece. Until 1965, the Comstock law had made it illegal to send photographs of the male nude through the US Postal Service; even in the 1970s, it was a provocative gesture to exhibit photographs with full-frontal male nudity. The critics were particularly hostile.

Inevitably, then, Bruce de Ste. Croix was singled out even though it was only available for purchase at the gallery, and not exhibited on the wall. “One young man sits in a chair staring at and holding his enormous erection, finding neither comfort nor use in his sex, stymied and baffled in a desert of excess,” Ben Lifson wrote in a review in the Village Voice. “The nude in Art is a matter of convention. In photography it’s difficult because everyday experience doesn’t readily proffer naked people to say nothing of men with phallic symbols between their legs.”

Advertisement

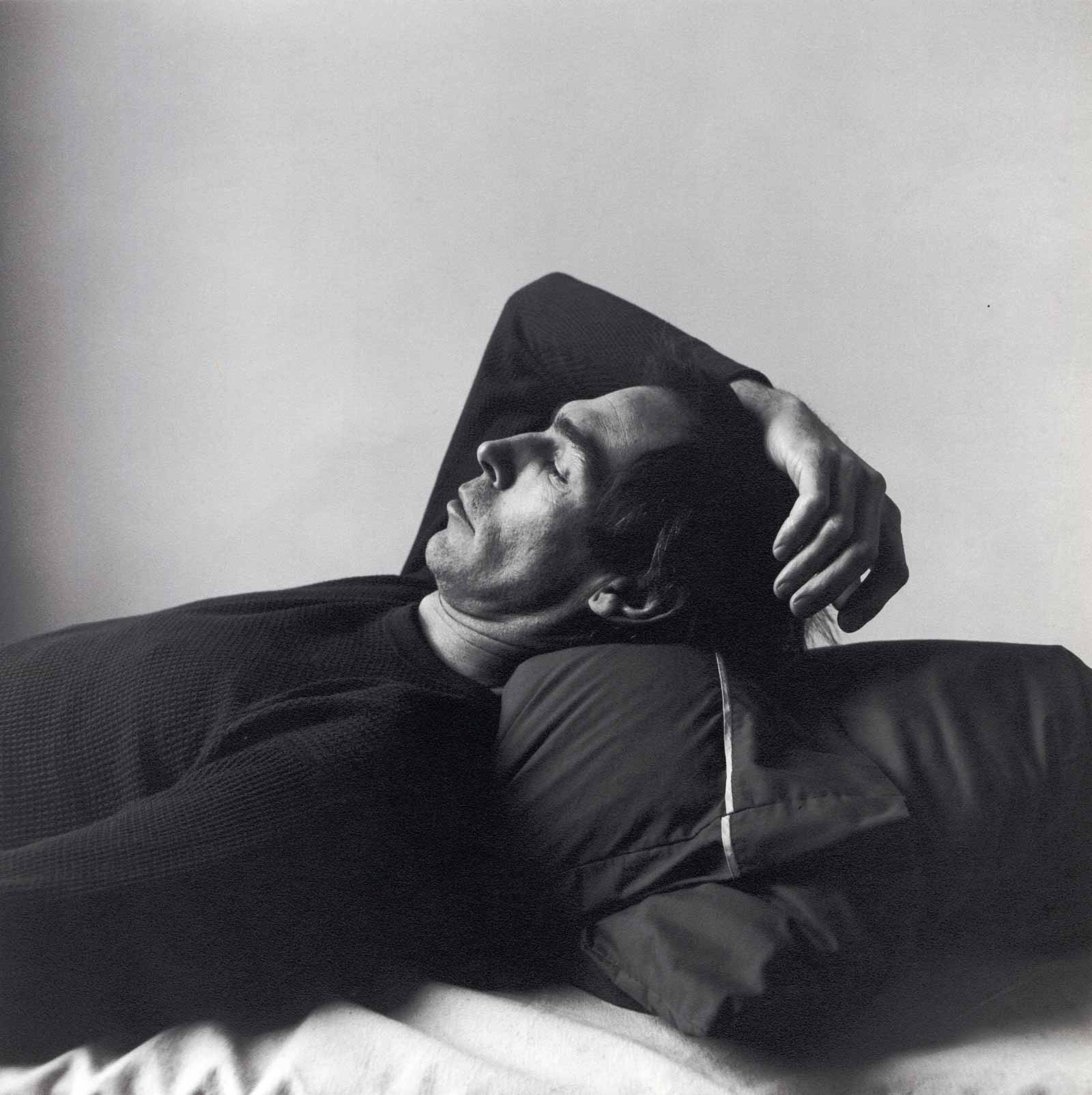

Theater was one of Hujar’s preoccupations, and among his friends and sitters was the director Charles Ludlam, founder of the Ridiculous Theatrical Company, whom Hujar had hailed as “our Cocteau.” Hujar’s portraits are intimate, quirky, well composed, and often quite beautiful. In Charles Ludlam, Morton Street (1) (1975), Hujar photographed the director lying on pillows against a bare white wall and gazing downward, capturing his pensive intensity. A hallmark of Hujar’s portraiture is the invisibility of technique—a kind of visual innocence—as if the camera were not present and the subject had been happened upon, discovered there, as Ludlam appears to be, in medias res.

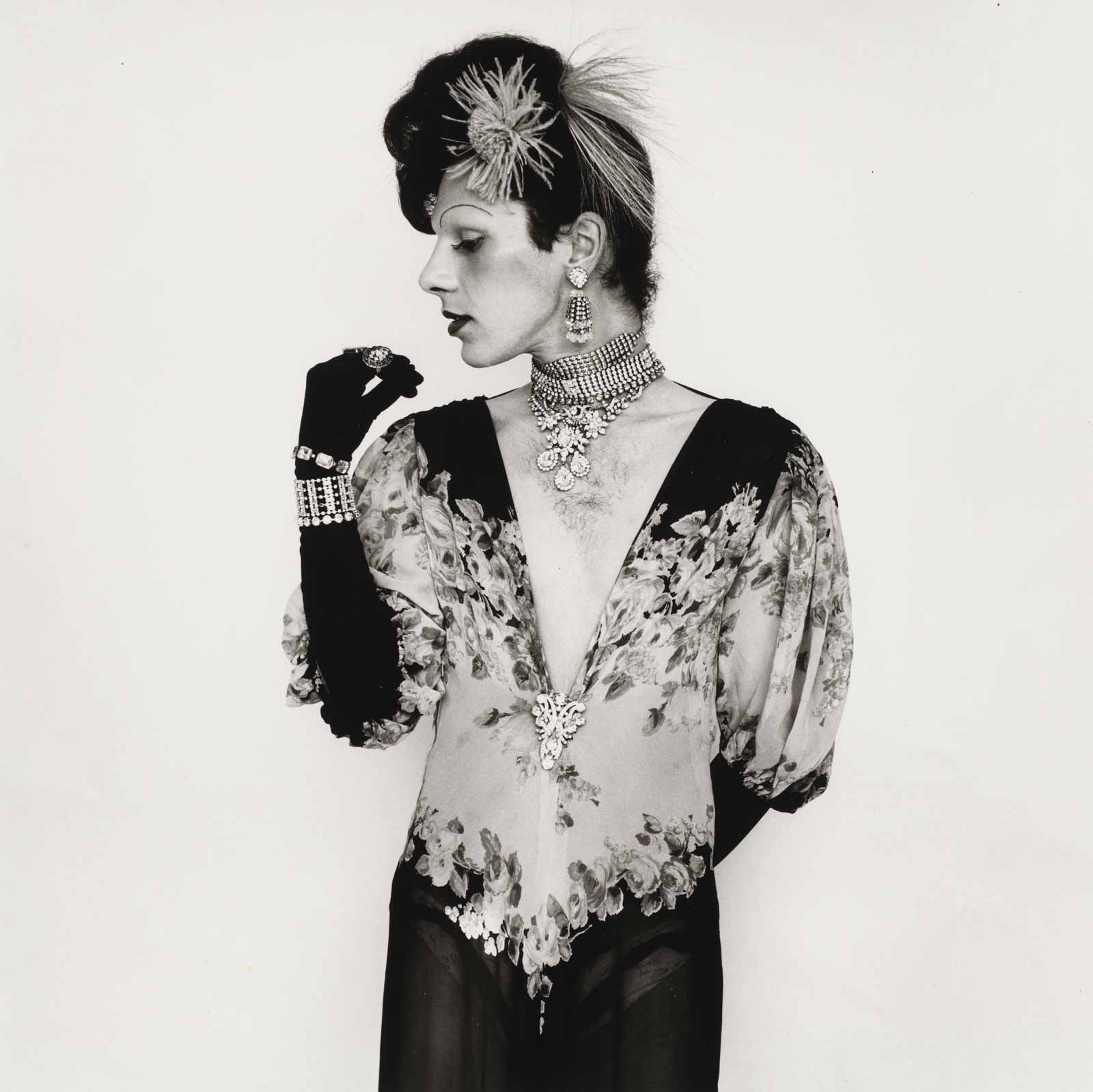

Among his most stylish portraits is Cockette John Rothermel in Fashion Pose (1971), which arguably ranks among the finest portraits in the history of the medium. Rothermel was a member of the Cockettes, a flamboyant theatrical troupe from San Francisco that brought antic humor to their wild, gender-fluid performances. The portrait exudes glamour and humor, poise, camp, ornamental beauty, exquisite grace, and iconic stature. The combination of elements—Rothermel’s slender frame, the impeccable period clothing, plunging décolletage, sensually draped fabric, florid deco pattern, layered jewelry, discreet hat, “struck pose” with bracelet over glove, and demure expression—all cohere harmoniously.

Hujar’s portraits of his downtown demimonde belong to a tradition of photographic portraiture that includes Nadar’s lucid pantheon of artists and writers in nineteenth-century France; Julia Margaret Cameron’s romanticized portraits of poets and thinkers in nineteenth-century England; and Berenice Abbott’s steadfast portraits of her expatriate circle of artists and writers in 1920s Paris. Richard Avedon and Irving Penn seized the mantle for the remainder of the twentieth century, photographing the most accomplished artists and writers of their era. In Hujar’s portraits, though, the intimacy of his relationships with his subjects is a visible characteristic that is virtually absent in the work of his predecessors.

In 1964, Hujar sat for several of Andy Warhol’s Screen Tests, holding so still—as if he were in a photograph—that Warhol referred to him as “the boy that never blinked.” As the Warhol “camp” gestalt became ever more visible in the back room at Max’s Kansas City, Hujar was drawn into the gender-obfuscating theatrics of Superstars Candy Darling and Jackie Curtis. Their life-as-art gestures were as much a kind of nose-thumbing at convention as they were sincere displays of each performer’s personality. The media attention that this group attracted in the late 1960s and early 1970s would turn out to have revolutionary significance, paving the way for the gay liberation movement and queer politics.

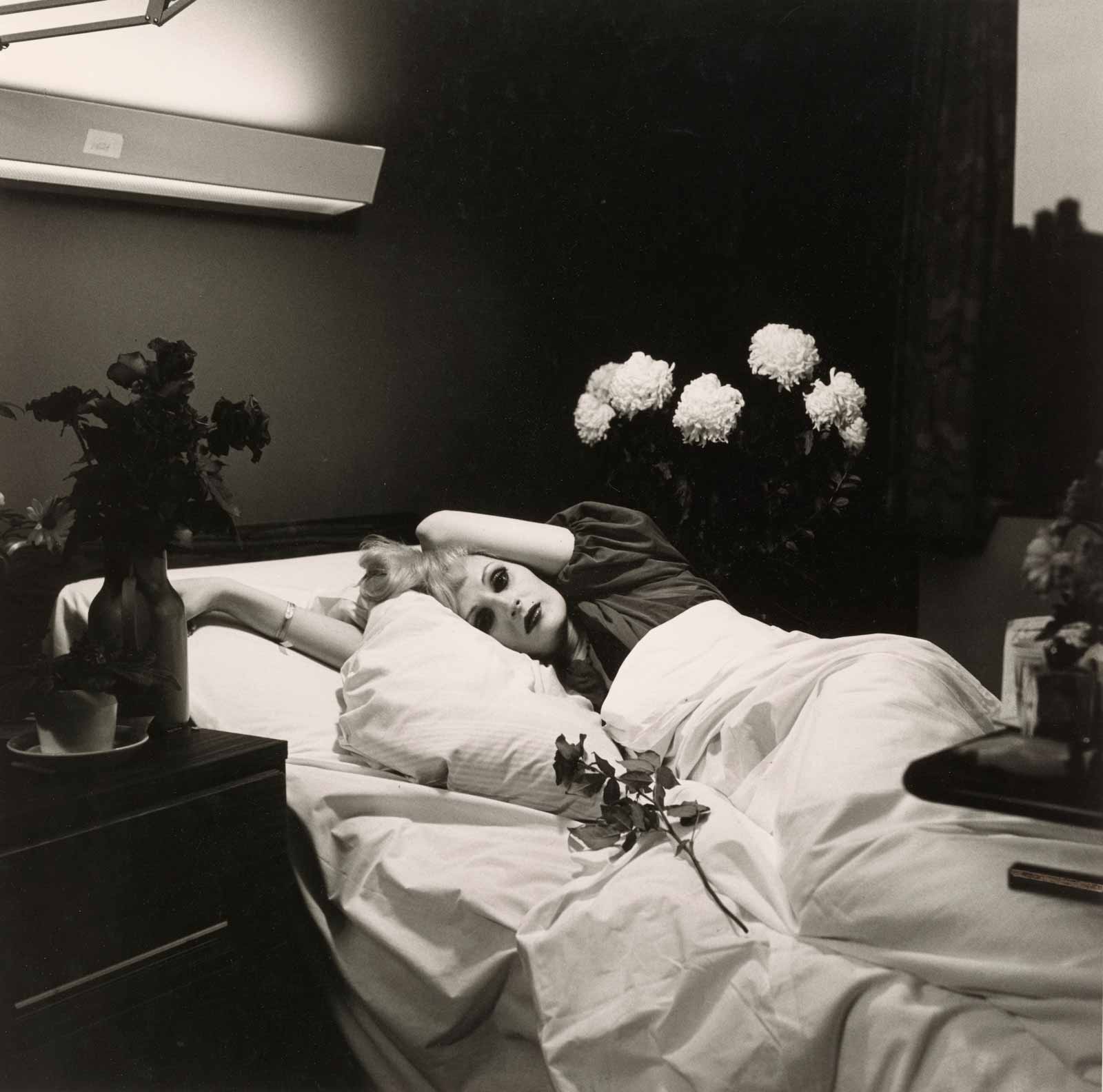

In 1973, Hujar photographed Candy Darling at Columbus Hospital six months before she died of lymphoma. Candy Darling on Her Deathbed is imbued with the glamour of a Hollywood film still, conveyed through the subject’s reclining gesture, tousled blond hair, and movie-star makeup. A closer look reveals a contrast between the utilitarian hospital bed, ordinary sheets, makeshift vases, and spotty bouquets of flowers and the bella figura performance that Candy Darling was “camping” up. The glamour Hujar found was in Candy’s final reach for sublime artifice; he later wrote that she was “playing every death scene from every movie.”

Hujar met the artist David Wojnarowicz at a popular, bare-bones neighborhood gay saloon called The Bar in 1980, and they became lovers. Wojnarowicz, twenty years younger, was still finding his way: most of his creative effort at that point had gone into writing in his journals, but Hujar, who would become a productive mentor, encouraged David to pursue his talent as a visual artist. Cynthia Carr, Wojnarowicz’s biographer, recounted a conversation with him before he died (in 1992), which attests to how central Hujar was to his work: “Everything I made, I made for Peter,” Wojnarowicz said.

In 1987, Wojnarowicz would make a series of haunting photographs of Hujar in the moments after he died of complications from AIDS. The pictures contain multiple layers of meaning: Wojnarowicz as the stark witness to the death of a lover; his unflinching rage at another AIDS death; and his elegiac homage to a significant artist.

Hujar left several hundred photographs in his archive after destroying, with the help of his friend, the photographer Lynn Davis, hundreds of “unexhibitable” prints. He liked to stress the creative primacy of “the real ones,” as opposed to those who found ways to achieve mainstream renown. “Forget Marlene Dietrich,” he would say. “Greta Keller taught Dietrich everything she knew. You have to listen to Greta Keller.” He saw himself as a “real one,” and he was willing to sacrifice everything to be that, including the cultivation of museum curators or gallery owners who might have put his work forward in his lifetime, securing him a more favored place in art history.

Advertisement

In the long run, though, “Peter got exactly what he wanted,” his friend Steve Turtell said. “He once said to me, ‘I want to be discussed in hushed tones. When people talk about me, I want them to be whispering.’”

Adapted from Philip Gefter’s essay in Peter Hujar: Speed of Light, the catalog published by Aperture and Fundación MAPFRE that accompanies the exhibition by the same name, on view at the Morgan Library & Museum through May 20.