“And one thing led to another, and so for months I did hundreds of drawings and they seemed to form a kind of story line, a sequence.”

“Freedom is the only possession an artist has.”

—Philip Guston, 1973, 1978

As a graphic novelist, I’m occasionally asked by civilians if my work is “political.” I usually explain that the time it takes to draw lengthy pictorial narratives (years) isn’t commensurate with the cultural immediacy (days, if not hours) that political cartooning and its creepy uncle, caricature, demand. On top of that, I’m no good at likenesses. Plus—though I never actually say this part—the last thing I would want as my artistic legacy would be a stack of Mitt Romney, George Bush, and Strom Thurmond cartoons. In the grocery store of art, political cartooning has the shelf life of an avocado.

In the summer of 1971, the painter Philip Guston, one of the greatest artists of the twentieth century, began a series of drawings under the working title of “Poor Richard” that grew out of his disgust and fascination with Richard Nixon. Philip Roth, the writer and Guston’s close friend, offered encouragement to Guston in his pursuit of Nixon-as-subject; their anger at the path America was taking and, as Roth told Charles McGrath in a recent essay about the drawings, their “shared delight” in Nixon’s “vile character” buoyed their regular conversations. Drawn in the aftermath of Guston’s critically excoriated Marlborough Gallery exhibition of paintings of cigar-smoking Klu Klux Klansmen, these genuinely weird and directly narrative drawings were so wildly out of step with the non-objective, non-narrative, non-everything of the fine art world that they ended up largely unseen and unmentioned for decades.

Did I say “narrative”? If I had in, say, art school in the 1980s, which I attended, I would’ve been laughed out of class. For those non-fine art readers for whom relating anecdotes of their supermarket trips to their spouses is second nature, I remind you of this bit of art-world history: for decades, narrative and representation were basically off the table. Around World War I, someone (was it Duchamp? McCarthy? I wasn’t paying attention) realized that the eye—formerly known as the primary means of perception—lied, and reality was really particles and uncertainty and now it was time to move along, nothing to see here. Fair enough, not only because this is actually true, but because a lot of that nineteenth-century stuff had gotten so gauzy and lush and, worse, adorned the walls of the very classes that had brought us the horrors of war. Golden reapers and dunked Ophelias and begonias on the veranda. Yecch!

Problem is, one has to look at a painting with something. All sorts of roundabout approaches to finding a representational loophole that would appeal, or, even better, sell, amid the mid-century witch-hunt against imagery—Pop Art, Op Art, and Photorealism in the 1960s, for example—ended up still being somehow “meta,” or what David Foster Wallace might have called “titty-pinching,” even if they were sort of fun to look at. What was really missing was the story, the life behind the image itself. That story, which once was the province of popes, saints, kings, and golden reapers, had been magically yanked out like a tablecloth. I found it confounding that in art school I was regularly told I couldn’t tell stories with my drawings but was still compelled to memorize art history. It was as if the story of art was more important than the art itself.

Which made it even weirder when I’d sheepishly admit to my instructors that what I really wanted to do was draw comic strips, and I’d be shunted toward artists like Daumier and Rowlandson, whose satirical and political subjects were so remotely nineteenth-century that their work seemed frozen and inaccessible. I’d mention Robert Crumb or George Herriman or Gary Panter and get a dismissive guffaw; “No no, look at Daumier. Or Goya.” Okay! Sorry I brought it up.

My discovery of Philip Guston’s work, first in the great 1986 Robert Storr monograph and then in Night Studio, his daughter Musa Mayer’s 1988 memoir, was like a rope thrown over a wall of a prison in which I’d voluntarily incarcerated myself. The direct, humane way she portrayed her father’s frustrations and struggles not only made him painfully real, but her mention of several sheets from a yellow pad covered in “an angry scrawl” that she discovered in his desk eventually became the key that turned the lock of my own jail cell: “American Abstract art is a lie, a sham, a cover-up for a poverty of spirit.… Where are the wooden floors—the light bulbs—the cigarette smoke? Where are the brick walls?” Talk about a story! This was one I could finally get with.

Advertisement

The seventy-three original “Poor Richard” drawings, as well as ones edited out by Guston and discovered by Mayer “pushed way in the back of the same drawer” (these desks and drawers of Guston’s perhaps need their own exhibit in the Museum of Modern Art), were assembled, framed, and rushed to exhibition in October of last year by Hauser & Wirth gallery in New York before Hillary Clinton’s victory as America’s first woman president would, it was assumed, push them past their sell-by date. Following the one-two punch of Trump’s nomination and election, however, Guston’s Nixon was suddenly fresher and more chilling than anyone could have wished it to be. The attendant marvelous catalog, published this year, includes all of Guston’s Pilgrim’s Progress of Nixon’s life, with outtakes, as well as informative essays by Debra Bicker Balken (reprinting her lengthy 2001 essay written to accompany the first publication of the original drawings), a transcription of a gallery panel discussion of the works, and another wonderfully clear essay by Musa Mayer.

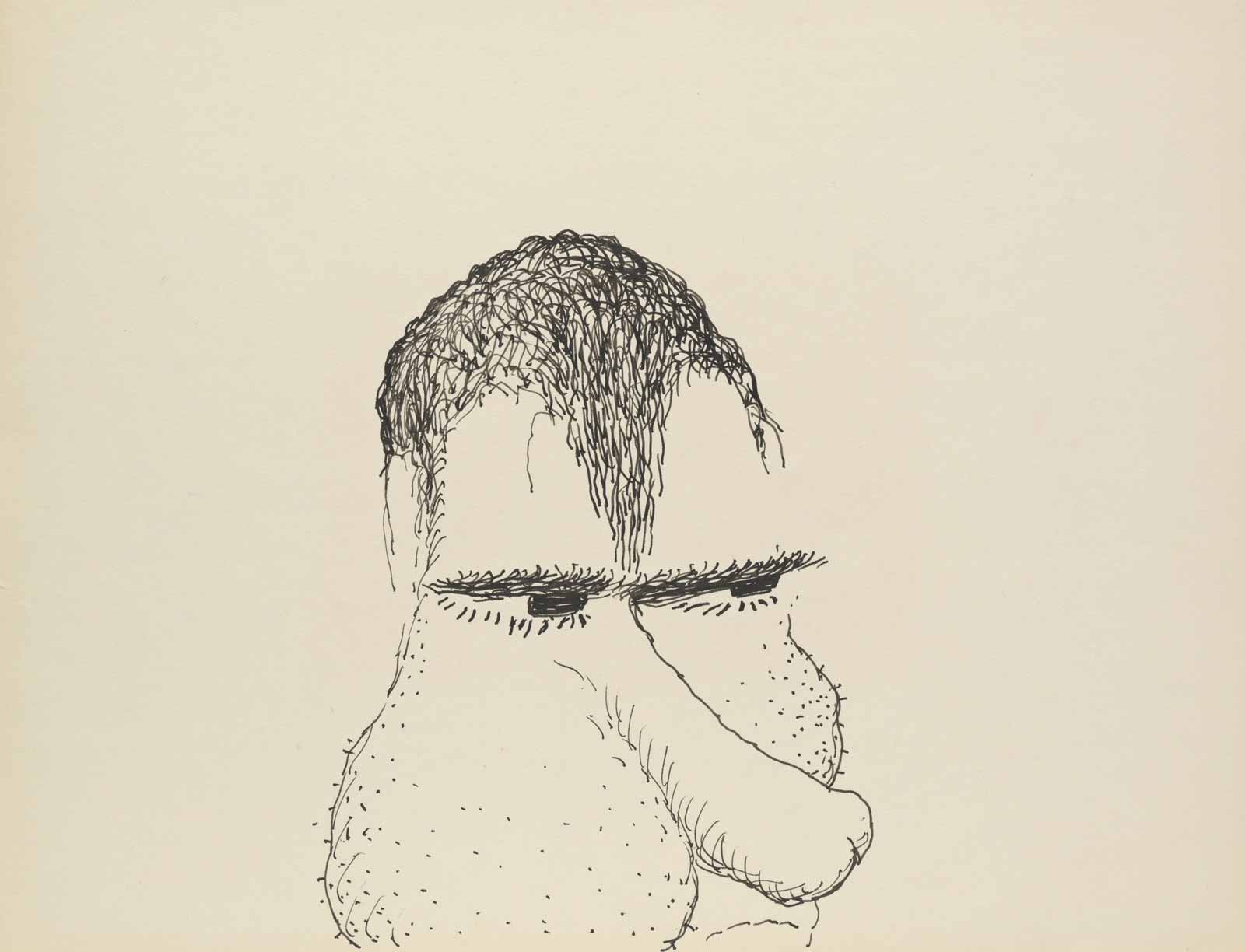

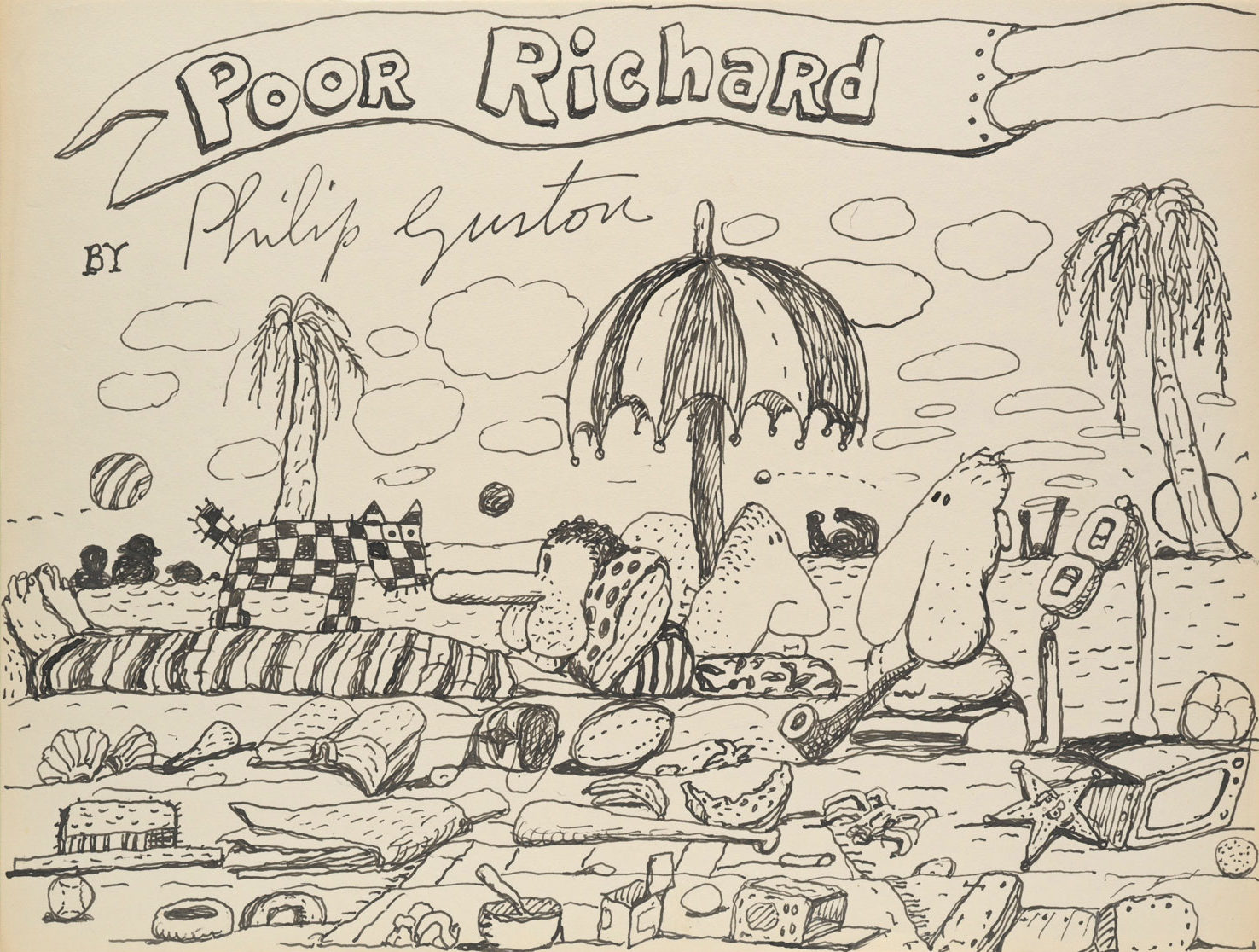

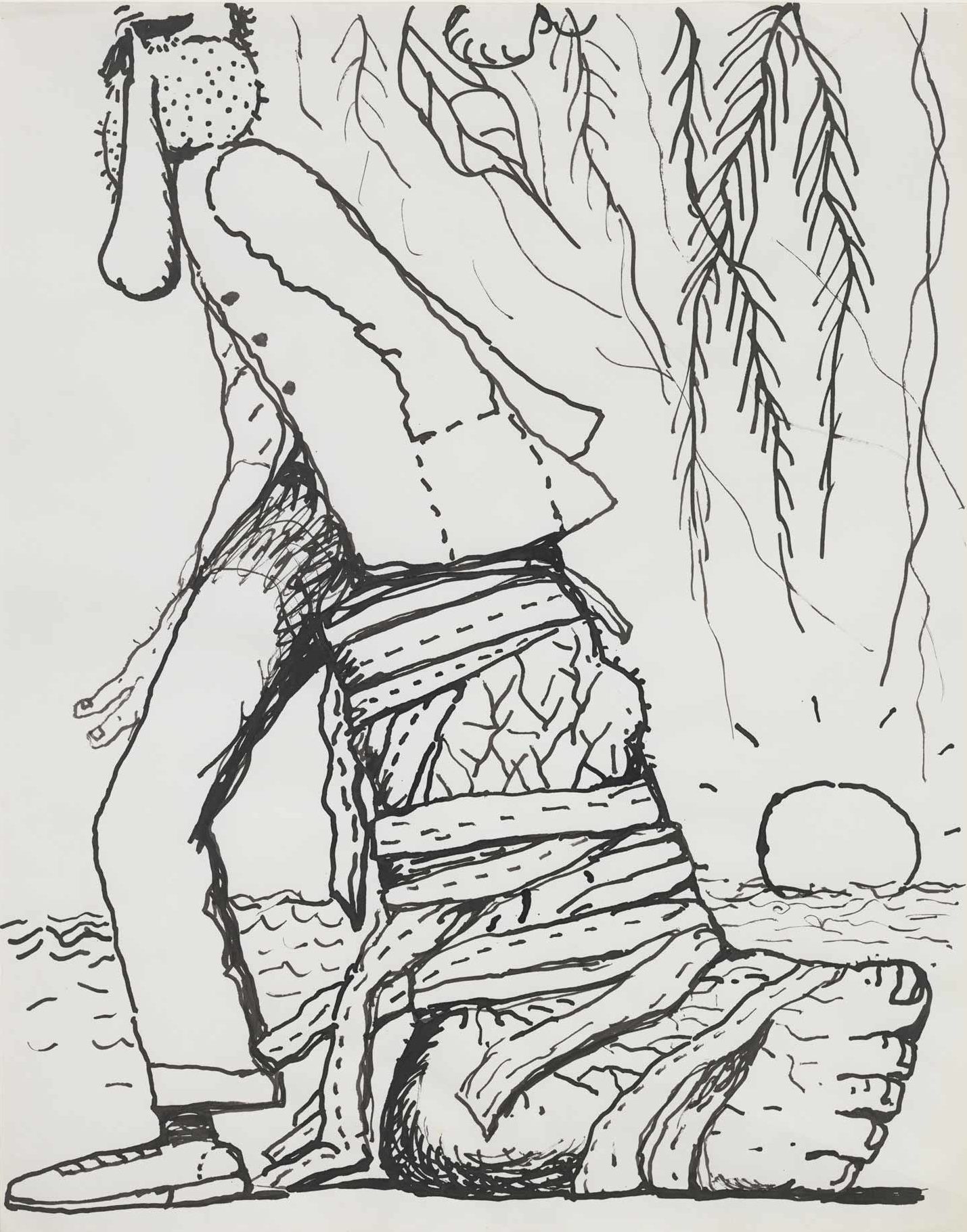

What surprises me most about all of the “Poor Richard” drawings is not their recognizable imagery, their directness, or even their satirical and political subject matter, but the fact that Guston apparently intended them to be assembled as a book. He even put together “large black pocket binders” with Xeroxes of the drawings to schlep around to potential publishers. Philip Guston was working on a graphic novel?! Well, not really. Though it tells a story, loosely threading together vaudevillian gags about Nixon’s coming of age (both he and Guston were born in 1913), Nixon’s college years, early political career, his “Checkers” speech, disappearance/reinvention, and election, his trip to China (with it all petering out somewhere in Asia with the characters pictured as spongecake and cookies), one passes through the images much as one might flip through an illustrated children’s book—without actually reading the text. The earliest frontispieces (Guston tried different versions—the original title was “Satirical Drawings”) show a hairy ink bottle with a Nixon-genie rising out of its uncapped top, highlighting it as a collection of cartoons. Perhaps later, after he got into it, he seems to have gone back and drawn something that focuses on his cast of characters qua characters: Nixon, Spiro Agnew, John Mitchell, and Henry Kissinger reclining on a Florida beach surrounded by the paraphernalia of American idleness. (“Reclining” might be too generous of a description, too, since only Nixon himself has a body; Agnew and Mitchell are lumpy, dumpy heads and Kissinger appears simply as a pair of thick glasses; he is the “eyes” of Nixon throughout the latter part of the story, seeing him to ruin.)

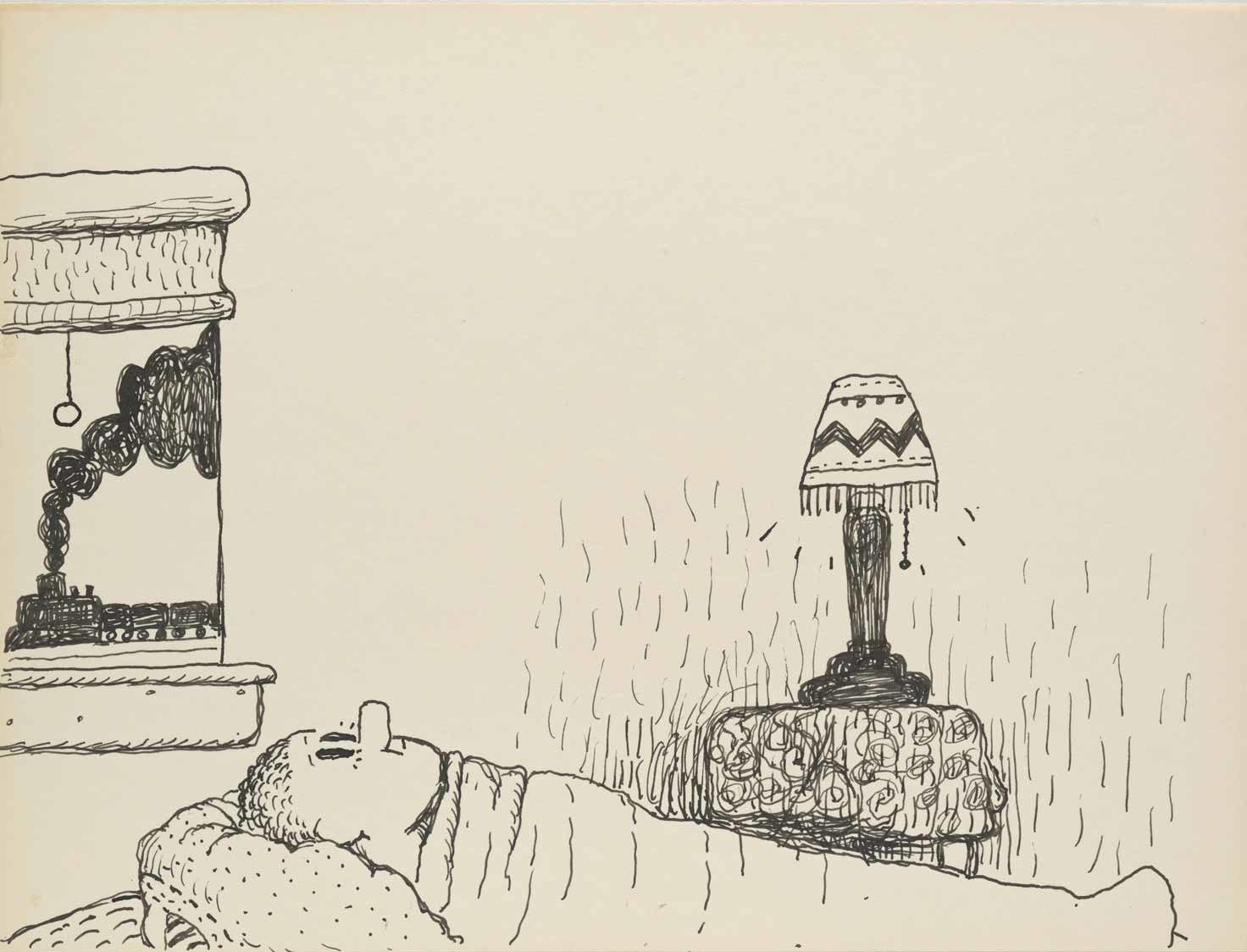

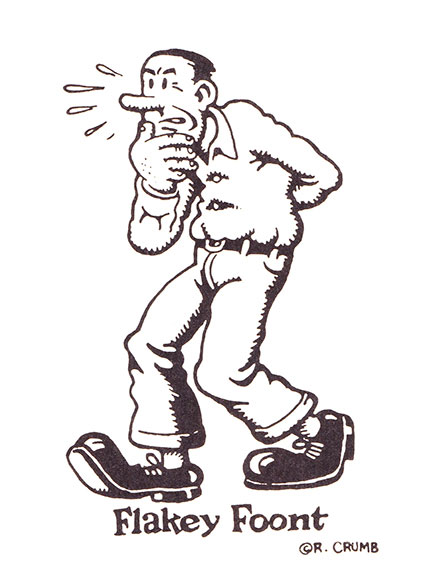

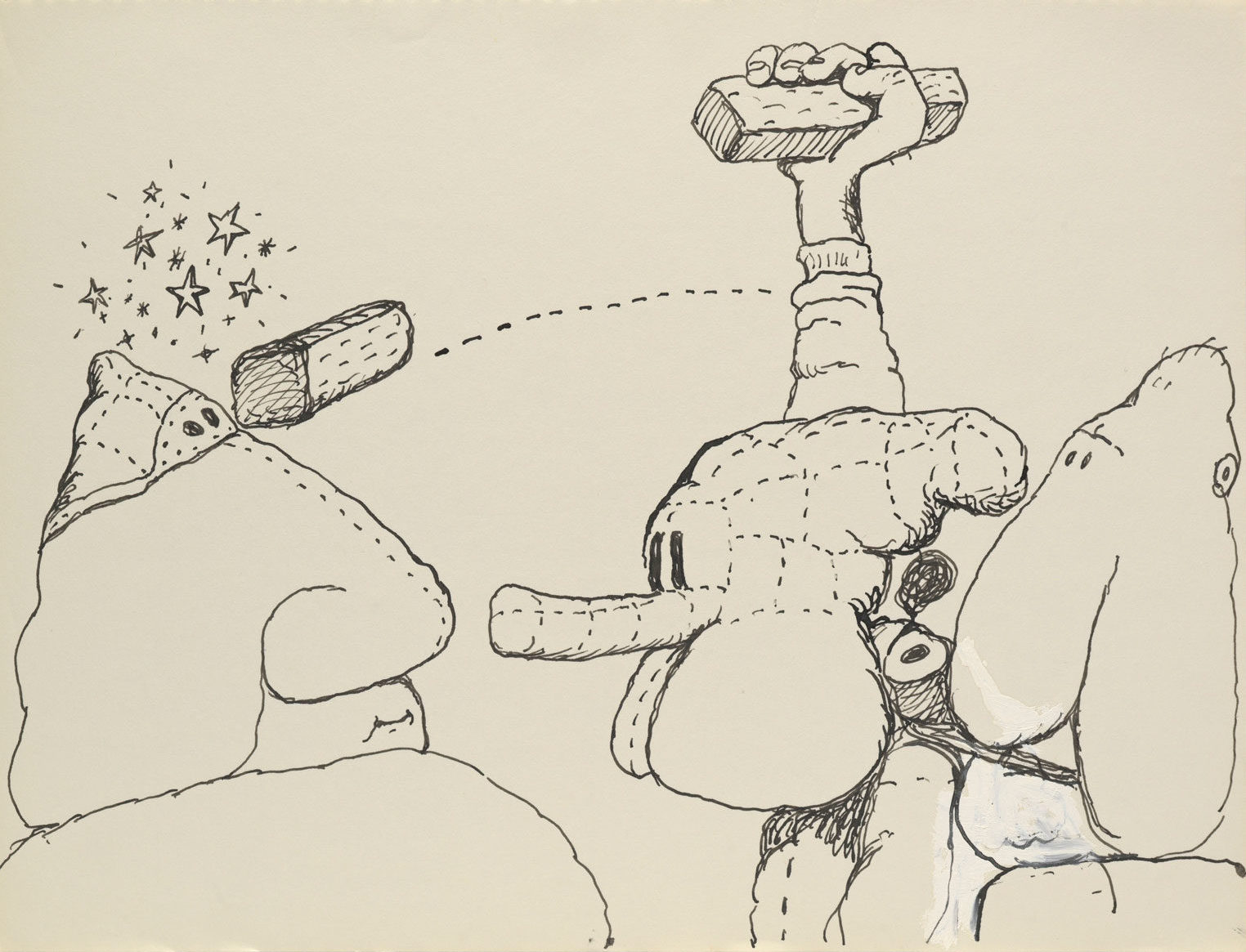

The ongoing visual gag of the book, especially as Guston finds his groove and really gets going, is Nixon-as-dick, or Tricky Dick with chin as hairy scrotum and nose-dong—sometimes priapic, sometimes flaccid—though Nixon’s earliest appearances are almost certainly internalizations of Robert Crumb’s Flakey Foont, a sort of everyman character blindly shuttered by American lies and ambitions until his enlightened old Squirrel Cage pal Mr. Natural blows his mind with the cosmic truths, or at least tries to. (The paintings Alone (1971) and In Bed, II (1971) also resemble the character.)

At the time Guston did these drawings, the so-called “underground” comics of the 1960s were, if not well-known, certainly not unknown, and were even on something of a downswing by 1975, the date of the last drawings in the book. It seems highly unlikely that hippie comics would’ve escaped Guston’s radar; even the artist Saul Steinberg kept copies of The East Village Other folded open to Kim Deitch’s strips as inspiration. (The critic Irving Sandler, a participant in the transcribed gallery talk, states that Guston “read everything. He knew everything.”) Guston entered a correspondence course in the Cleveland School of Cartooning when he was thirteen and was known, along with Willem de Kooning, to admire George Herriman’s brick-loving Krazy Kat (from which Flakey Foont-Nixon also draws some slight, however racially inverted, inspiration)—of which the catalog rightly takes note. And, just as my instructors might have also noted, Nixon-as-ballsack could even be traced back to nineteenth-century French caricaturist Charles Philipon’s abbreviation of King Louis-Philippe as a saggy pear (“Les Poires”)—which was apparently a gag so popular in his day that other cartoonists stole it freely. (I would’ve, too.)

Advertisement

There’s certainly no lack of Nixon imagery in the cartooning canon from which to steal, and as crazy as it might sound, Nixon’s endurance in generational memory may be helped along by Guston’s work, or may even eventually break free of history entirely. (What do I know of Louis-Philippe, anyway?) Certainly, Spiro Agnew and John Mitchell are already fading in the popular consciousness and may survive more vividly as the pyramidal pile and pipe-stuck penis they exist as here, cavorting on Florida beaches and costume parties dressed as Klansmen with an attendant blackface Nixon—Guston’s sumuppance of Nixon’s southern strategy, which, reimagined by Trump in 2016 by appealing to out-of-work whites, helped him sail to victory. Amazingly, Guston even tries actual comic-strip dialogue balloons and narrations, as well as a childlike interpolation of quasi-Mandarin characters as Nixon and his sidekicks ascend the summit of Asia, represented as either a mountain or an approximation of “Chinese” architecture. The overall affect is weird for those of us familiar with Guston’s paintings and semi-representational drawings: a real clanger, like the handful of experiments when Charles Schulz showed adult legs in Peanuts or drew actual teenagers in his one-panel Young Pillars Christian cartoons. Yikes!

Guston’s abstract-expressionist paintings of the 1950s (which followed his earlier work as a social-realist WPA artist) are almost synesthetic impressions of form, and might be described as visual phonemes, the painterly equivalent of James Joyce’s implantation of imagery in the reader’s memory with what seems like, but clearly is not, nonsense. From this frozen state of near absolute-zero objectivity, Guston took baby steps in the 1960s back into the warmth of visual language with marks and shapes that suggest, though do not form, imagery—then, by the time of the Marlborough show, they do, and wildly so—but it was too far and too much for everyone, and so rained down the criticism. As Mayer points out in her introduction, the freedom he found in the self-sustenance of a story seemed to have opened the floodgates to a wealth of imagery he would mine until his death. “My painting comes out of drawing. I couldn’t live without drawing,” she quotes him saying, and Phong Bui, the moderator of the transcribed gallery discussion, cites Guston even more pointedly opining that “‘pictures should tell stories. It is what makes me want to paint.’”

Some of the transitions between these pictures in the story of Poor Richard start to sputter and almost crank up the actual comic strip engine, the characters once or twice seeming to come to life on the page as might, say, Krazy Kat or Charlie Brown, especially in the latter section of the story where they all seem to visit China. The visual repetition of certain elements (the noodle bowl into which Dick dips his nose, the car/rickshaw in which they travel) encourages the mind to begin to “read” and compare the drawings as theater rather than as the visual metaphors they are. By and large, however, the illusion of life and drama on the page is not Guston’s interest, his approach more like reportage in the “this happened and this happened and then this happened” way, as in the so-called “woodcut novels” of Franz Masareel and Lynd Ward, or, as my friend Ivan Brunetti has sharply pointed out, Picasso’s The Dream and Lie of Franco (1937) and Balthus’s Mitsou (1921)—though the tone of Guston’s work is more in keeping with cartoonist Milt Gross’s He Done Her Wrong (1930), a parody of Masareel’s and Ward’s work, though it lacks its theatrical propulsion. Moreover, Guston’s disposition towards his characters is more symbolic and associative, almost Steinbergian, as in, “What happens if I put this with this?” So few cartoonists of my generation (myself included) draw, or think, in this more poetic manner. Maybe we should.

This painter who made the first ever inside-out portrait of a human being (Head, 1975) must have at some point, perhaps even while working on “Poor Richard,” realized or remembered that stories eventually eat their pictures. Which is to say that an image put in the service of a narrative, especially one meant to be read (with or without words) is sucked dry of aesthetic independence by the very story it sustains; its presence and gravitas drain away in the service of a narrative. (Maybe that’s what the twentieth century was actually having trouble with, come to think of it.) Guston, the master of gravitas and eternity-in-paint, must have started to notice that his direct, near-illustrative images of Nixon and Agnew on the beach at Key Biscayne simply didn’t have as much staying power as his Platonically powerful paintings of heads, bottles, legs, shoes, and light bulbs. It’s a balancing act that every cartoonist and every painter must achieve, and the greatest cartoonists (Spiegelman, Crumb, Herriman) somehow manage it. But the painter who’d gone all the way down to nothing and back up again, in short, hit a brick wall, and backed off.

Even so, he chose Nixon as a subject for more drawings and a painting later on: the canvas of a crying Dick with phlebitic leg (San Clemente, 1975) summing up the general gist of “Poor Richard”—a tragic figure, perhaps even worthy of sympathy, wounded by his own ambition and ego. As Lisa Yuskavage says in the gallery talk, Guston “decided to not put these drawings out there because… he ‘didn’t want to be known as a Nixon hater.’” Irving Sandler adds that Guston and Nixon both had “second acts,” which perhaps the artist felt was a point in common, even of sympathy. Was Guston’s real strength, then, in his humanization of Nixon, his searching for some shared ground with a man his age who was otherwise opaque and devious? Recently, at a cartoonist dinner I attended that included Charles Burns, Gary Panter, Art Spiegelman, and others, Panter lamented that not a single one of us had come anywhere near the vicious, skin-flaying reveal that Trump necessitated and deserved. (Dash Shaw cited Daniel Clowes’s drawings of Trump’s parents for the political newspaper Resist! as the best he’d seen.) I wondered if empathy really was the key, given its so-crazy-it-just-might-work sound; but how does one empathize with a racist, predatory liar? It’s almost more than any artist or writer could manage. But it is indeed what we have to aim for if we’re going to get anywhere as a species.

This is stupid to mention, but I’ve sometimes thought that if we all wore T-shirts printed with pictures of ourselves as children it might soften the righteous bluster that seems to inform much of adult governance and litigation. (To say nothing of marital arguments: any time I think of my wife and her 1976 bowl cut, I really can’t get too mad at the way she wads up her towel and leaves it on the bathroom radiator.) Like Guston’s youthful Nixon in bed, if elementary school pictures of Donnie Trump and Kim Jong-un accompanied their public statements they might be more inclined to sympathize, if not empathize, with each other, or at least be more aware how their threats will affect millions of children.

A recent New York Times article highlighted an art exhibition at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in Manhattan featuring the work of Guantánamo prisoners. Encouraged to make paintings and other work as a way of passing time, the article focused on the legal arguments of the government (our government), which had decided that it retained all claims and rights to the prisoner’s work; that is, all of the drawings, paintings, and sculptures by prisoners were not their property and would be “incinerated” if they were ever freed. (In a double irony, meanwhile, the former president who put them there is having art shows of his own.) These men, as we unincarcerated Americans know, are being held on suspicion of terrorist activity with hazy non-plans for military tribunals conveniently free-floating in the legal limbo of Cuban waters for the past sixteen years. One of the paintings, by now-released Muhammad Ahmad Abdallah al Ansi, is of the Statue of Liberty. This image, to me, seems the most powerful, affecting, and damning of caricatures of us Americans yet.

Philip Guston: Nixon Drawings, 1971 & 1975 is published by Hauser & Wirth.