My mother used to count whenever she grew angry. I tried to make sure to get in order before she ever reached ten. Then, later, in the group homes, the ticking bomb of egg-timers was the soundtrack to every shared space. I set the egg-timer before a shower, before a phone call. The tick, tock like the crank of a jack-in-the-box on my adolescent nerves.

When I left the group homes, I was a pissed-off teenager: wild, gamey, and hot to the touch. I wanted to fix all the fucked-up things. I wanted to make my way into all the Offices of Importance and let them know I was somebody special, that I was worth something, that I was smart, that I could do whatever I set my mind to. Yet there I was, resigned to the fact that I’d been given a number, shuffled into a corner, where there was a file with my name on it. Should I do anything wrong—homicide, or a misdemeanor, or any type of failure, or fall into homelessness—the people would look at my file and understand: oh yes, ward of the court. The mystery would be solved.

But instead of following the trajectory set before me, I took a sharp left turn. I met a woman with a petition. This was something I could do. Get people to sign her petition. Her petition to get money from the government to build more schools and parks. I went to El Superior, the grocery store on Figueroa in LA, and stood out in the hot sun. I drank pink and white and green Agua Frescas, and had folks sign my petition. One hundred. I wanted to get one hundred signatures a day, I decided. That would be magnificent.

I learned early on not to mess with the people who had a bunch of questions, or those who clearly didn’t want to sign. The “I’ll sign for your digits” people. Or the “If they take the money from the military what will happen if we go to war?” people. The “Get a job!” people. I kept it moving, and went up to the people who were more open. Usually, black women over the age of sixty. Folks who knew the value of their own signature. Folks who could remember a time when they could not sign. People who recently went through the naturalization process just so they could sign, or senior citizens who could recall a time when voting was not as accessible. The people who read the small type. They were my favorite people.

Later, I got a job as a telemarketer. I’d call people to see if they needed to refinance the mortgage on their home, or I’d call people to congratulate them on winning a contest and a free trip in exchange for a short presentation and tour of a timeshare. It became clear early on that it was all a numbers game. I was great on the phone. I could dial fast; at the first sound of the busy signal, I’d hang up and move on to the next.

It reminded me of requesting songs to get played on the radio. There was an hour every evening when you could call in. I used a landline with a brick-red handset, a rubbery caricature of little Orphan Annie glued onto the part that nestled in my neck. I’d dial the station once, at the first flash of a busy signal I’d hang up and press the redial button. I did not fuck around. I’d go for a hundred calls in a row. Fast. By the hundredth dial, someone would pick up and take my dedication: Lucky Star by Madonna, from Melissa Chadburn to Jessie Gottlieb.

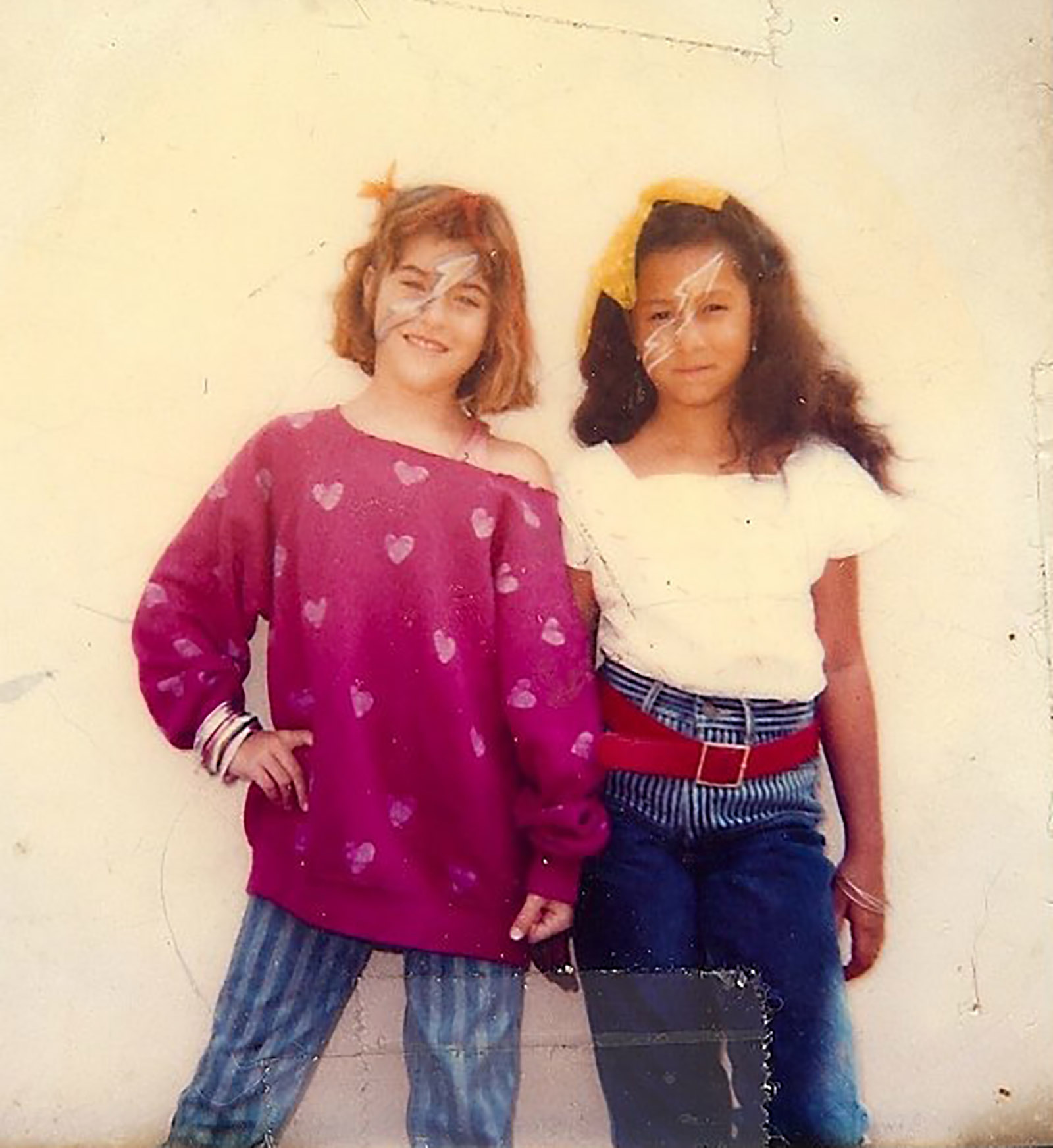

Jessie was a fellow latchkey kid. I’d walk to her place after school, we’d drudge up change for candy at the local gas station, we’d get drunk off Manischewitz for New Year’s. She’d boss me, and do my hair, and tell me what to wear. She was my best friend and my first love.

Every year around Halloween, when most people were out with their children dressed as goblins or bananas, or were out getting turned up dressed as nurses or Freudian Slips, I’d be canvassing— shaking gates in small red towns in central California. Fresno, Bakersfield, or, closer still, Orange County. The housing projects in Fresno often have poker tables beside the door with grapes laid out to dry and become raisins. After a month in Fresno, I did not want to see another raisin, the symbol of sweat and grief and poverty, small hands picking, heads in bandanas and big wicker hats, swarms of flies, and no breaks. A large banner across the field declared, “Vote For Me!” and featured a photo of the white man who owned the land and had a house on a hill. The farmworkers called him “patron.” He was the boss; they would vote for him.

Advertisement

My job was to try to see if they could be persuaded to do otherwise. Vote for the woman who supported a union contract, the woman who believed in healthcare, bathroom breaks, safe and fair working conditions. A hundred conversations. I would not go back to my hotel room until I got a hundred yesses. Yes, I will vote. Yes, I know where to vote. Even though it was late October, it was hot as hell. There was a drought. Poverty. Fresno was a place with no water, where people slept out in the dusty sun, thirsty. As I made my rounds, I shook gates to make sure there were no dogs in the yard. When I wasn’t talking to voters I was off capturing runaway pit bulls because of some gardner or some mailman who came before me, and every time I was capturing runaway pit bulls I wasn’t talking to voters. Again, I didn’t waste my time on the “Decline to States” or the “Not Homes”—or the folks who pretended not to be home. Out in those parts, the homes had dark metal screens, so that people could leave their front doors open to let the hot air from cooking escape—but you couldn’t see shit inside. I could hear grease popping on their frying pan and someone belting out oldies—love songs about estrangement or all the desperate things they’d do for their boo, be puppets and babies and sha-la-las.

One year, I talked to a man three times. He fed all the strays in the neighborhood. This guy had never voted before. I drove him to his polling place. He said that he enjoyed it, he would do it again the next year. I wrote out on a piece of paper the name of the person I thought he ought to vote for. The person who I thought had his best interest at heart. I also brought him some dog food to help feed the strays. Even though it took away from my hundred contacts that day, I will remember him forever. He said his brother kept on stealing the dog food. If it wasn’t bolted down, his brother would steal it. There was a dog that was missing, he said. A small Chihuahua. I didn’t want to tell him about the dog I’d seen that fit that description, jerkied in an alleyway two blocks over. Flattened and stuck to the ground, like the black peppered stuff they sell at the flea market. Our candidate lost.

Later, I was sent to organize healthcare workers. I went to live in an Extended Stay America in Santa Rosa. I spoke to my best friend every day while I sat outside smoking American Spirit Menthols, dodging deer that came to graze on the mountain behind the smoking cabana, and people high on drugs who’d taken up a much more permanent stay at the motel. The elevator of the place was so damn lonely, a showroom for the new face of eviction. A woman moving in with a box that held pots and pans and cereal boxes, her cat beside her. A man in his Walmart uniform his lunch packed in a plastic bag heading into work every morning.

Life as a union organizer: every week, I had a new goal for my hundred. A hundred pledges to vote “Yes” on the contract, a hundred people to wear purple T-shirts, a hundred people in a department to conduct a work stoppage, a hundred people to march on the boss. Marches on the boss were my favorite. I’d run around and find out what pissed everyone off. Maybe it was the way overtime was handed out—like candy to besties—or parking that was unsafe and faraway or expensive, or sick time, or breaks being withheld, or some boss trying to cut corners by beefing up production without providing the necessary equipment to do the job.

I learned how stingy pathology laboratories are with those smaller, sharper needles. When I learned what pissed everyone off, I also learned who was the leader, who had all the Tupperware parties or brought cake on birthdays, who raised the most money for their kid’s magazine drive and sold the most Girl Scout cookies. And that person would help rally everyone to demand that they got better parking or put an end to the favoritism for overtime. I’d agitate, just like in elementary school: “Look at you, there’s a hundred of you guys. And only one of those miserable, cheap, lazy sons of bitches. You gonna let ’em do you like that?”

Advertisement

No, no, they would not. And we’d all come together and march to the boss’s office. And sometimes I’d take an overblown list of demands, or a giant check for five cents, or some sort of papier mâché something, and—of course, of course—the boss would acquiesce because their offices were so nice. They had a standing treadmill desk and plants and Kuerig coffee pods, and the longer we hung out in there, the more we’d notice all their fancy shit. But also, we were disrupting the air in the office. The boring, static, nothing, bullshit air.

Also, the Consumers were outside. They didn’t want the Consumers to catch a whiff of trouble and take their healthcare business elsewhere. Yes, yes, they would fix it. But before they fixed it, we would force the Baddest Bad Boss of all to stand up and apologize to the people—apologize to their hundred workers. And we would chant our happy asses out of that office: ¡Si Se Puede! ¡Si Se Puede! ¡Cuando luchamos ganamos! When we fight, we win!

It was in that Extended Stay at that podunk town that I got dumped. I was sad, embarrassed, lonely. Just my pit bull and me, some rain. No good food. I wanted to cook. I wanted to go to the grocery store. I wanted my cat. I wanted to be in my bed in my house, but there was one thing that I wanted more than that. I wanted to get published. I’d been writing but only occasionally sending work out to be published at one random place or another. That’s when it hit me. My one hundred rule. I needed to use the same thing I had already learned about gathering signatures for petitions and getting out the vote and union organizing, and apply it to getting published. Rather than scattershot-submit my writing to a bunch of different, random places, I would create an organized, methodical submission system. I would submit to one hundred publications.

I decided I was no longer just a union organizer staying in some motel. I was officially on a writer’s retreat. I submitted one story to one hundred different publications. When it was published I celebrated with cheap pizza in town. In time, the more pieces I got published, the more uppity my system became. I developed a tiered submission chart. I submitted to top-tier publications first, then worked my way down the list. Each year, my goal was to publish in a better tier than the last. It worked. I still use that submission process today. Each year, I break into a better tier. I wanted to be the person to tell my narrative, the narrative of a brown girl who grew up in foster care, a girl whose mother taught her how to sharpen a pencil with a steak knife, a girl who grew up sweeping the carpet. The people in these top tiers, most of them, they didn’t have my story, they had other stories, but they learned about these elite publications when they were at Columbia or Iowa.

Writing has brought a thousand rejections, telling me that I am a piece of nothing, asking me who I think I am, charging me with being a class traitor. This is a feeling that hooks into my gut and anchors me back into my childhood. Sit down!

But my people are trudging people. Where I live, every week before street cleaning, I watch a woman with gloriously thick, long witchy white hair chug a dolly loaded with a car battery up the street. She plunks the battery into a big gold van that holds toys and bags and boxes and tools and the detritus of parenting her two grandkids. She starts up the van, says her Hail Marys, and then moves it to the opposite side of the street. Sometimes, she has a couple of guys with her. One who appears younger than her but is in a wheelchair, one older than her barking instructions, “Pump the brakes, pump the brakes.”

She does this again, the same ritual each week with two cars, the other is a small black car crowded with papers and laundry baskets and children’s games. She’s so determined and, you would think, stern, but later in the afternoons I see her cruising down the street on a bike, her granddaughter beside her wearing what I can only call a Ferris-wheel grin. Complete abandon. I want to buy her a car or a battery or whatever it is she needs that would mean she won’t have to do this anymore, but I don’t have any money; and anyway, maybe she would find something else, something equally frustrating that fills that time. Because my people are trudging people.

I know deep down every “No” just gets me closer to my “Yes.” The “No” cuts me, but the cut is familiar. I’ve been told many times that because I, too, have been a kid with a number, I might be too biased to report on the system that dishes out the numbers. Because I’ve had the scarlet shame of food stamps, I might not be able to write objectively about state-funded benefits. But if we aren’t qualified to tell these stories, who is?

I used to blame the discrepancy between those of us willing to hit send and those of us too afraid of a shut door on the gender gap, but now I realize it’s a privilege and power gap. We trudgers, we’ve all got one thing in common, though: nothing to lose. It’s a numbers game. Just hang up and dial again. One hundred. One hundred.

This story was supported by the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.