Frank O’Hara, the “poet among painters,” as Marjorie Perloff dubbed him in the title of her 1977 study, is an emblematic figure of the Sixties New York scene. Mario Schifano’s name may be less familiar. The Roman painter, eight years younger than O’Hara, never made much of an impact on the American scene, exhibiting in New York only twice during his lifetime (he died in 1998).

That O’Hara and Schifano had known each other and had collaborated was never exactly a secret—but the fact has been pretty well ignored by O’Hara’s many admirers. Perloff never mentioned Schifano in her book, the first scholarly monograph on the poet, critic, and curator who had died eleven years before in a freak accident, run over by a dune buggy on Fire Island. Nor does his name appear in the index of Brad Gooch’s fact-filled but “relentlessly superficial,” as David Lehman wrote in The New York Times, 1993 O’Hara biography. In Joe LeSueur’s Digressions on Some Poems by Frank O’Hara: A Memoir (2003), Schifano’s name appears in a long, long list of artists whose work O’Hara owned—“a motley crew of the famous and the unknown, the talented and the not-so-talented.” O’Hara’s Collected Poems includes one dedicated to Schifano, a marvelous little symphony of interruptions, of swervings away from and back to the sudden intimacy of its opening—“I to you and you to me the endless oceans of / dilapidated crossing”—that seems, as a whole, to suggest an unrequited desire. Which only makes sense. O’Hara’s weakness were alcohol and men (and they didn’t have to be gay), but Schifano’s were women and drugs.

The collaboration between O’Hara and Schifano is fully realized in the eighteen-page-long Words & Drawings, just published in its entirety in a beautifully designed and printed edition by the Archivio Mario Schifano in Rome (unfortunately, in an edition of just 300 numbered copies, plus fifty hors de commerce, which means that it still won’t be as widely seen as it should among admirers of the poet and the artist; though it is a step forward considering that, until now, just four pages had been published in an obscure journal from Palermo).

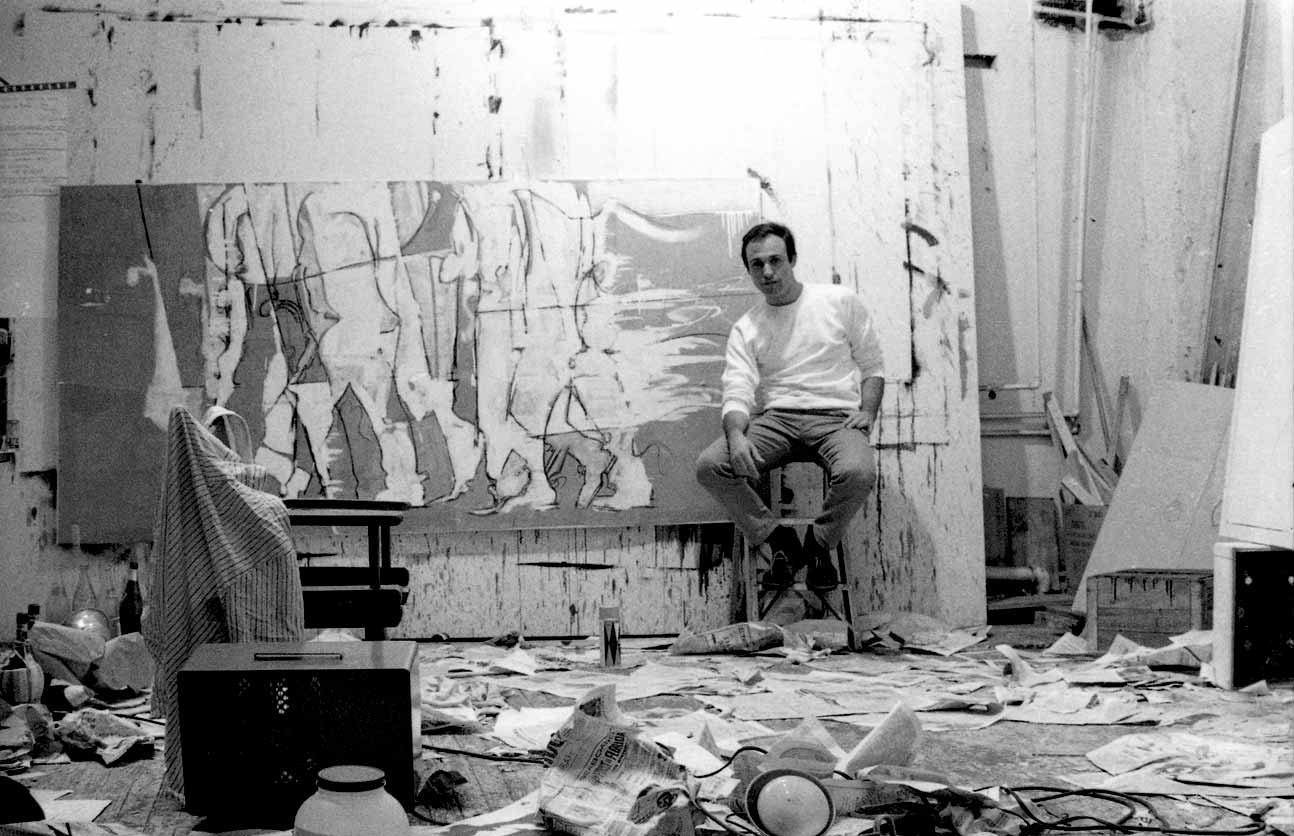

It was after a December 1963 ocean crossing, nine days in rough weather, that Schifano showed up in New York with his model/art student girlfriend Anita Pallenberg—later the companion of the Rolling Stones’ Brian Jones, until she paired off with bandmate Keith Richards instead—and found a studio sublet at 791 Broadway, where O’Hara and his partner LeSueur were among the neighbors. “America was like a dream, another world,” Pallenberg recalled. Schifano was not alone in being obsessed by the new art of Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg. A Roman friend gave them “a little package” to deliver to a certain Vito Genovese in New York; what they brought the former capo di tutti capi is unknown. The couple stayed through the following July, when they returned to Italy despite Schifano’s having just written to his friend the critic Maurizio Calvesi that he intended to remain: “I feel great being so distant from the delicious and useless city of Rome.”

Although Schifano’s work had been included in the prestigious “New Realists” exhibition at the Sidney Janis Gallery the year before, artistic New York was not welcoming to the Italian visitors: this was the era when European art was supposed to be outdated. As Raphael Rubinstein notes, in a thorough historical essay on the O’Hara/Schifano collaboration, the show at Janis had been “seen by many as an American-European confrontation in which the European artists appeared less advanced, less contemporary than the Americans.” The New York-based Italian journalist (and, later, politician) Furio Colombo compared Schifano’s arrival to crashing a party.

O’Hara, Pallenberg recalled, was the exception who greeted the young visitors warmly. He took them to the Five Spot Café on Cooper Square, which today everyone remembers because of O’Hara’s poem “The Day Lady Died,” where they heard musicians such as Thelonious Monk and Charles Mingus; Schifano introduced O’Hara and his friends to the great poet Giuseppe Ungaretti, who’d come to lecture at Columbia. What might have made Schifano’s art look a bit behind the times to many New Yorkers—its focus on landscape and the figure, however removed from naturalism, and the primacy it gave to drawing—would have been just what endeared it to O’Hara, who was unhappy with how the New York scene was evolving. He had not entirely facetiously dubbed his own style of poetry “personism,” but the new art was suddenly going all cool and impersonal.

Advertisement

He couldn’t abide Pop art, for instance; nor, later, would he take a shine to Minimalism. When Andy Warhol approached O’Hara about posing for a portrait, the poet turned him down flat. “But you pose for Larry Rivers,” Warhol objected. “You’re not Larry Rivers,” was O’Hara’s comeback. Rivers’s high-spirited pastiches of old-fashioned history painting still looked fresh to O’Hara—an art spared from “theoretical considerations and / the jealous spiritualities of the abstract,” as he’d once written. A similar compromise between rebellion and tradition is evident in Schifano’s work of this period, particularly in his collaboration with O’Hara. The affinity between Schifano’s work and Rivers’s was clear enough to the young Donald Judd, still better known as a critic than as an artist, in his dismissive review of Schifano’s 1964 show at the New York branch of Rome’s Odyssia Gallery, for which O’Hara’s “Poem—for Mario Schifano” served as catalogue text.

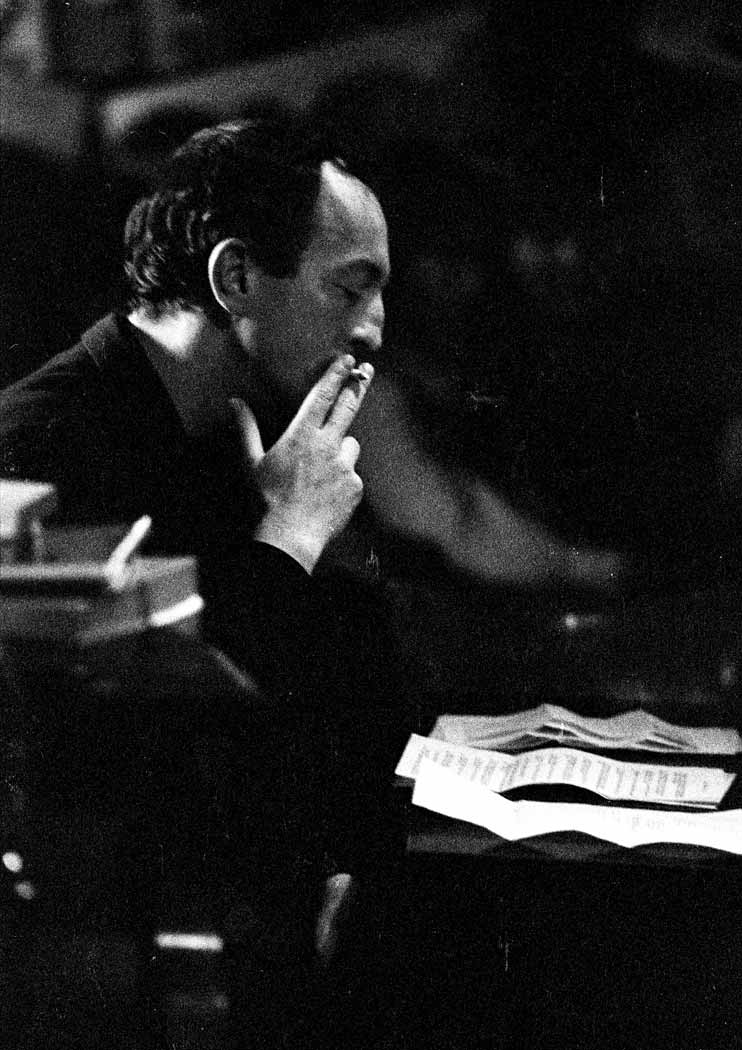

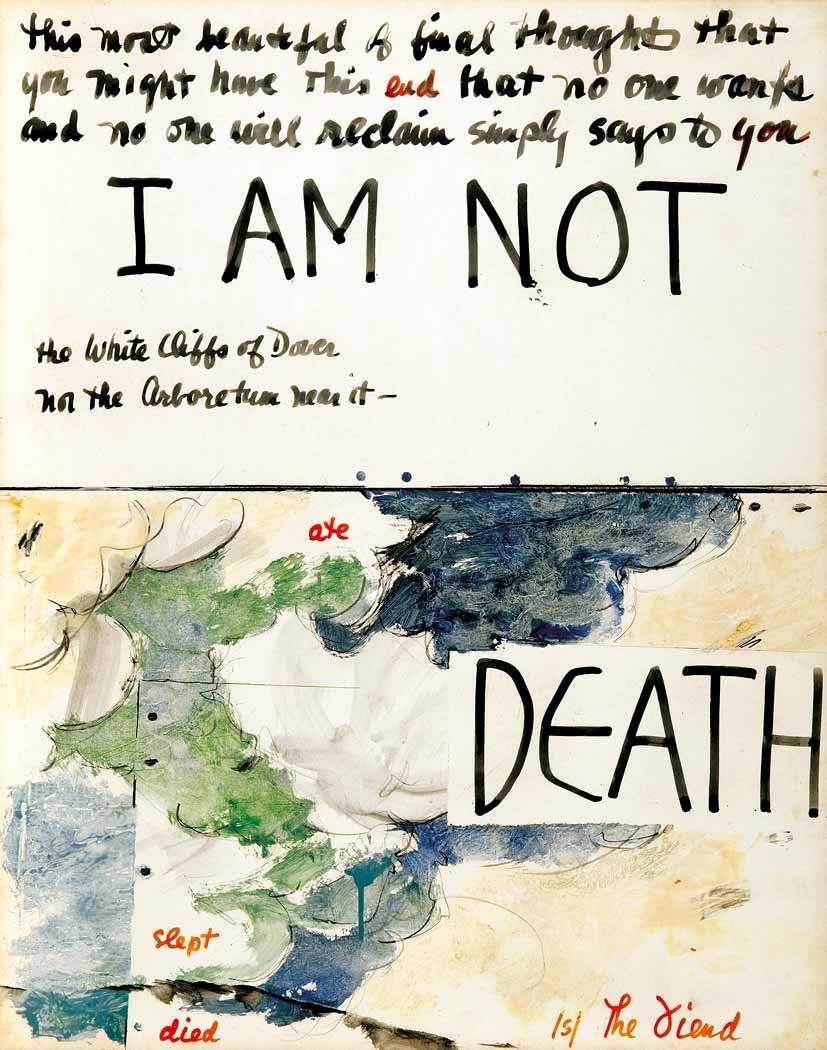

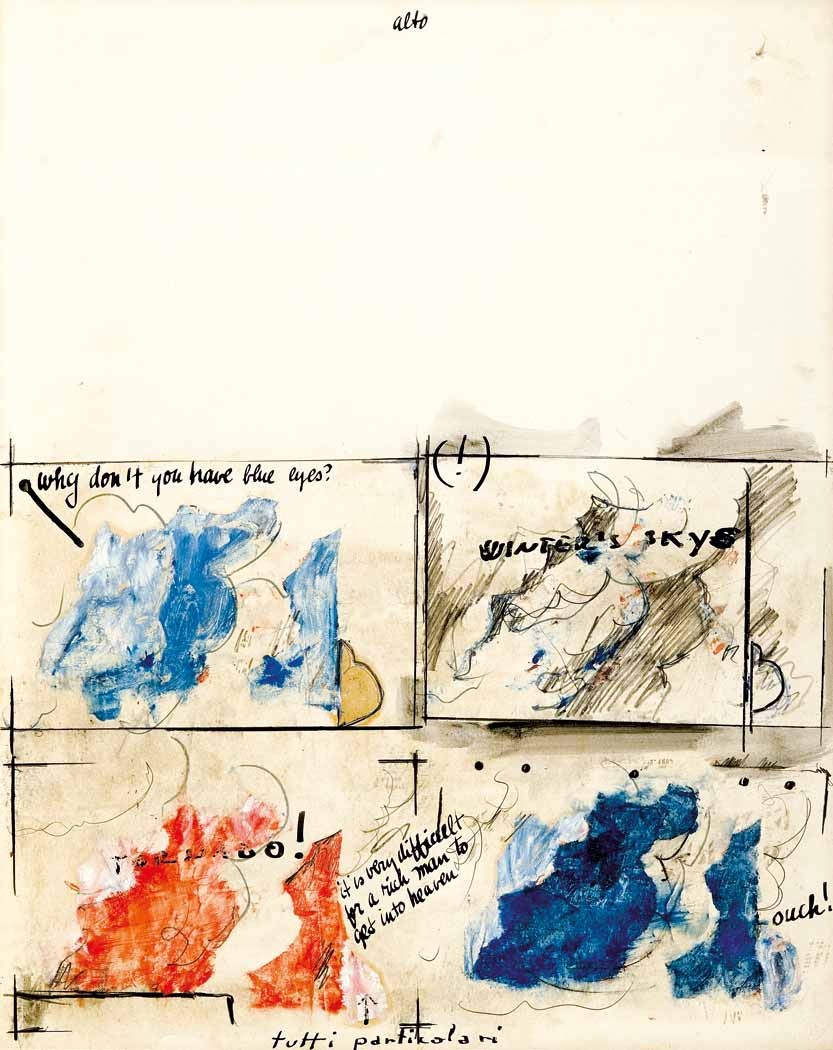

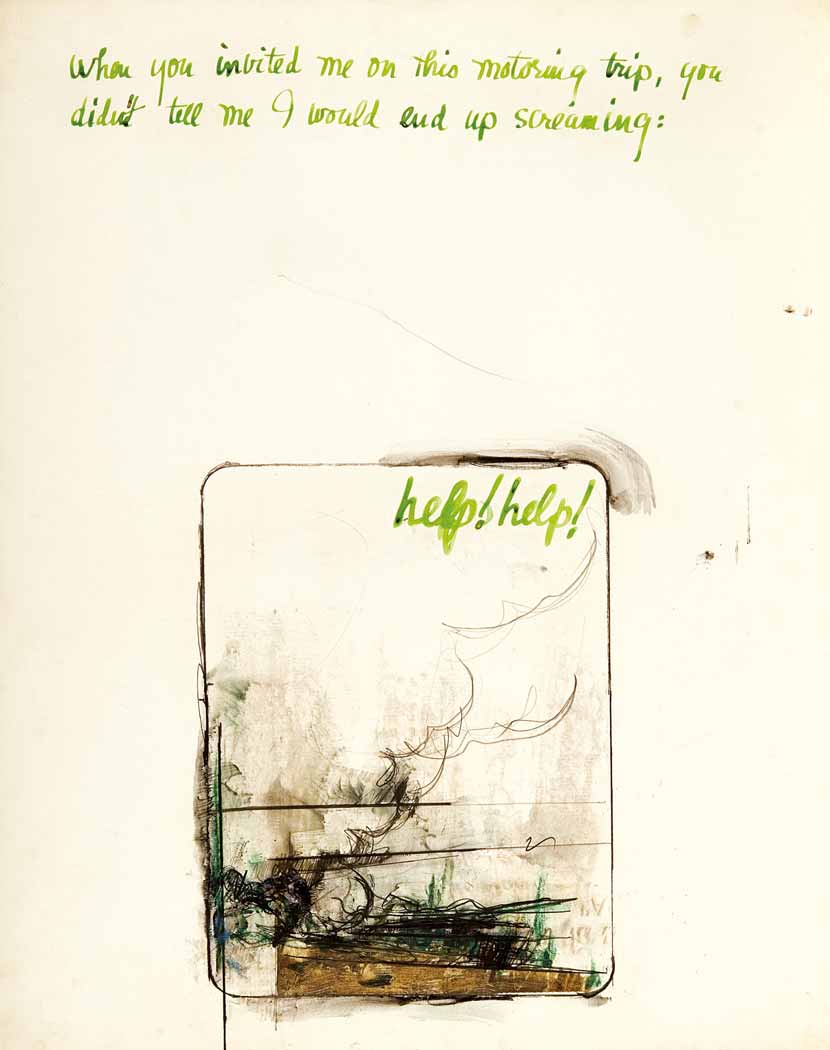

O’Hara, immersed in his work as a curator at the Museum of Modern Art, was writing hardly any poetry at the time he met Schifano, so the very fact that he undertook the collaboration, which was exhibited later the same year in Rome and then disappeared into a private collection, suggests that the Italian artist inspired in him some special impetus. And yet, he begins the text with what sounds like an attempt to hide some trepidation about the collaboration behind a tone of campy melodrama: “When you invited me on this motoring trip, you didn’t tell me I would end up screaming: help! help!” But by midway through the text, it has become impossible to tell whether O’Hara is speaking for himself or ventriloquizing for his painter friend: “When I remember the skies of Italy / in New York / the quatrefoil mess of testicular eyes / which are not stars / no place seems ever / to have existed.” As Rubinstein suggests, “the quatrefoil mess” would be the stained-glass window of Grace Church, across the street from the studio in which O’Hara and Schifano were working. But death haunts the text—that of the recently assassinated President Kennedy, certainly, and more broadly, in the lines “this end that no one wants and no one will reclaim.”

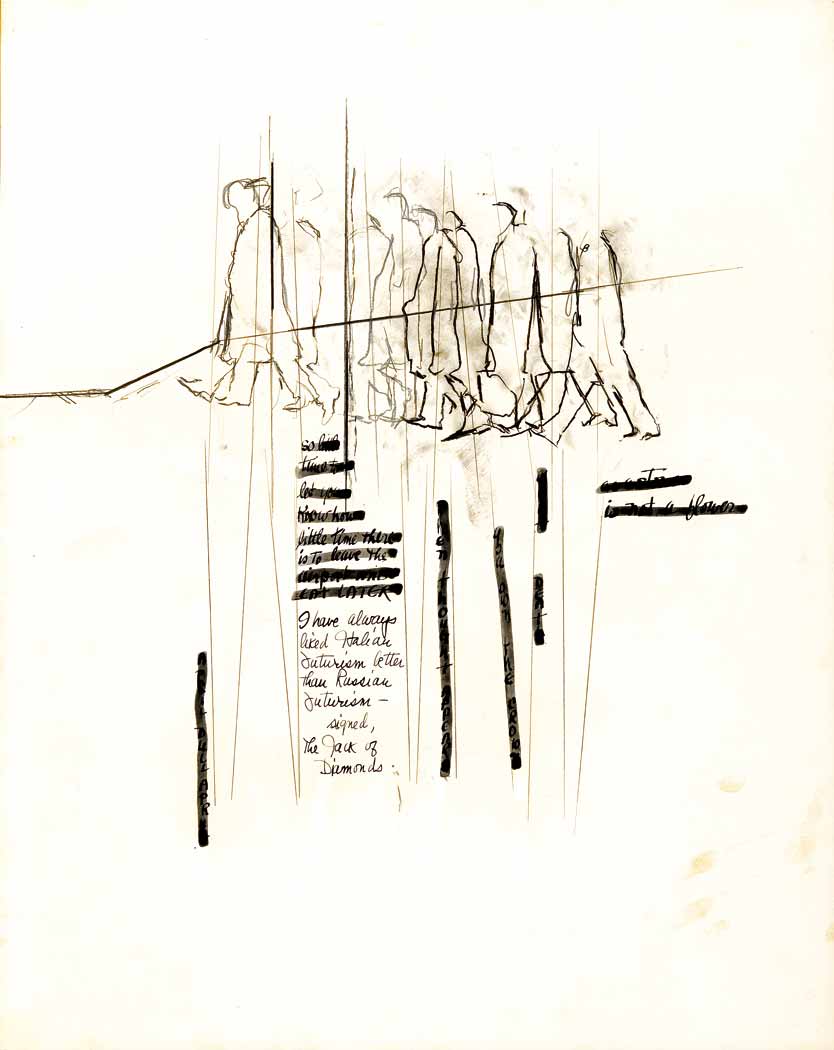

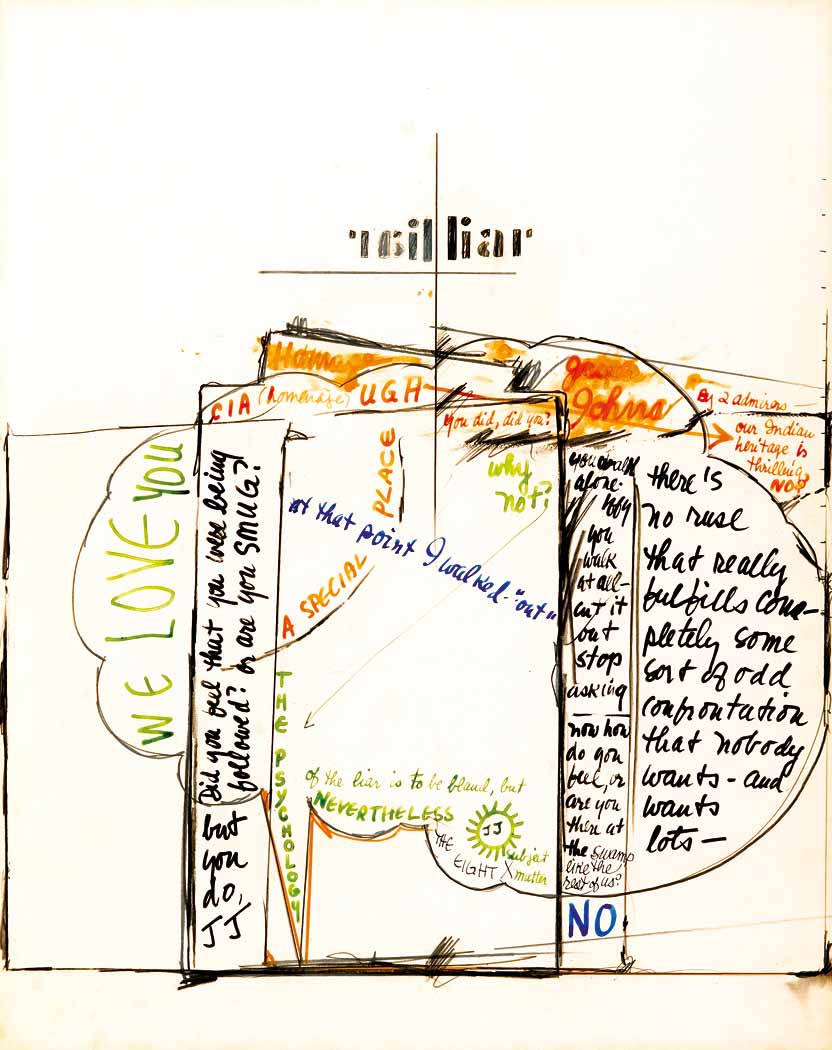

Their collaboration seems shadowed by the figure of Jasper Johns. Sheet 6 is headed by the stenciled word “liar,” which is also mirrored—mirroring and stenciling both being typically Johnsian moves. Beneath it, “Homage to Jasper Johns” appears half wiped-out, as if it were a mistake meant to be seen. (Throughout Words & Drawings, handwritten words—ranging from intensely lyrical poetic fragments to stray conversational fragments and lists of names—are O’Hara’s, stenciled words are Schifano’s: words that are also drawing.) Liar is the title of a 1961 work by Johns, a study for a painting that was never made—and it was done directly after a painting that Johns did finish, In Memory of My Feelings—Frank O’Hara (1961). In the Johns, the title word is mirrored top to bottom, rather than left to right as with Schifano and O’Hara. The inverse word represents a wooden block that would have been used to stamp the word into the painted surface below; the critic and art historian Leo Steinberg saw this as “an allegory about the hinge between life and art.”

In Schifano’s drawings, urban life is insistently evoked, often in the form of walking crowds of people—yet it seems almost infinitely distant: the people are empty outlines in an intangible space. Life has been swallowed by art. The schematic quality of things is not cold, but melancholic. On the last page, signed “goodbye, Harry xxx,” everything seems to be blowing up in a mushroom cloud.

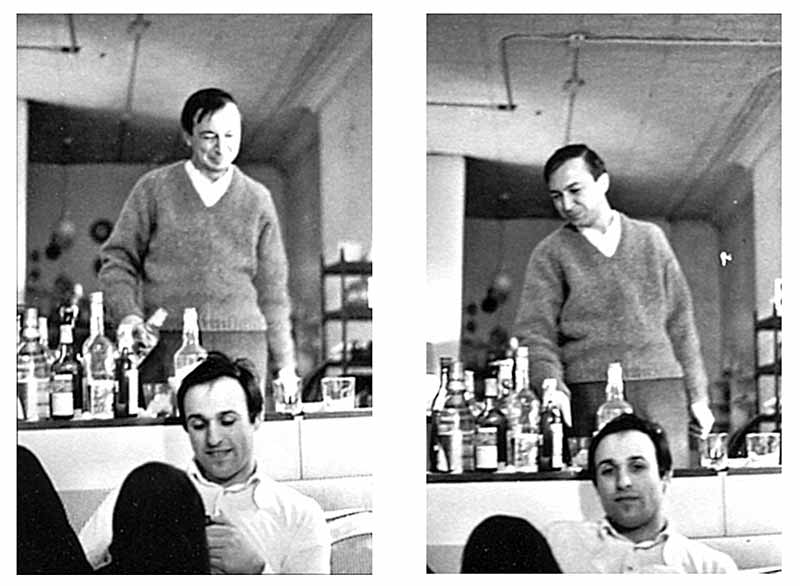

But the end of the book is not the end of the collaboration. Temporarily, at least, Schifano was getting ready to replace the paint brush with a camera as his main tool. He spent much of the 1960s making experimental films. But here, we see him observing the city and its people with a still camera. Take away Words & Drawings, take away the mostly excellent texts, by Pallenberg, Rubinstein, Colombo, and others, and the volume published by the Archivio Schifano would still be precious for the more than 150 mostly black-and-white photographs by the painter: incredibly atmospheric views of the city, its streets, its teeming inhabitants, suggesting a voracious appetite for new sights. Looming angles show the buildings as seen by one who excitedly cranes his neck in all directions.

More intimately, we meet the denizens of New York’s overlapping poetry and art scenes—John Ashbery, Bill Berkson, Paul Blackburn, Joe Brainard, Gregory Corso, Edwin Denby, Allen Ginsberg, LeRoi Jones (later, Amiri Baraka), Kenneth Koch, Taylor Mead, Patsy Southgate, Jane Wilson, and, of course, O’Hara, Johns, and Warhol, too, among many others. These portraits reflect a slower, more insinuating gaze than the street scenes, seconding Colombo’s observation about Schifano’s subtle way of entering social situations: “He would gallop toward a new prey, then slow down and circle it… He participated even without listening.” In this scene, it was easy to circulate. “Almost everyone was someone else’s friend,” recalls Colombo. Schifano’s images put you in the midst of a long-ago party, and like the America he and Pallenberg imagined, it now seems a dream, another world.

Frank O’Hara Mario Schifano Words & Drawings is published by the Archivio Mario Schifano.