Weapons are metaphors. We use them in figures of speech (the pen is mightier than the sword) and as figures of speech (stick to your guns). The weapon-as-metaphor suffuses contemporary culture but it is perhaps nowhere more present than in the Marvel Universe. Thor’s boomerang hammer, Spider-Man’s sticky tech—they’re ripe with symbolism. In the franchise’s new blockbuster movie, Black Panther, Ulysses Klaue, a South African arms dealer with a missing arm, unzips his pants in the middle of a South Korean casino and pulls out a hefty curved slab covered in brown paper. It’s labeled “FRAGILE.” He slams it on a table and smirks. It is a joke so old that one of the earliest etymological variants of the word “weapon,” the Old English “wæpnan,” also meant “penis.”

Klaue’s phallo-weapon is the detached head of a pickaxe made of vibranium, the precious metal and major resource of the African Kingdom of Wakanda. It’s unclear whether the original item was a tool or a weapon, used for mining or murder—not that there’s much of a difference to Klaue, who also adapts an old Wakandan mining tool into a gun that he attaches to the end of his stump. This hand-gun, so to speak, later causes an explosion of cash. “I made it rain,” Klaue laughs hysterically at his own joke as bills float down around him.

This is the kind of double, or triple, entendre we expect from a comic book film, so familiar we pretty much slide over all that it implicates: masculinity, power, violence, money, and even the sly hint of overcompensation for a fragile ego. But the way that Black Panther uses weapons—the way it plays with them and makes them metaphors—becomes far more interesting as it proceeds. It is the crux of the film’s plot and affords some of its most striking visual and dramatic effects. Weaponry also predictably contours the film’s politics, and perhaps less predictably, its ethics.

The first weapons we see conform to type: T’Challa (a stoic Chadwick Boseman) barges in on his ex-girlfriend Nakia (a radiant Lupita Nyong’o) at work. She’s a spy in the midst of a night mission to “bring our girls home,” rescuing them from a Nigerian terrorist group dressed in army uniforms, riding in covered cargo trucks, and carrying automatic firearms. Bullets ricochet brightly across the dark screen as T’Challa, in his bulletproof panther suit, defeats the terrorists with martial arts. He receives last-minute help from Okoye (Danai Gurira), his bodyguard and general of the Wakandan special forces, the Dora Milaje, who calmly uses her golden spear to kill off a surviving gunman.

Okoye’s fierce loyalty and statuesque beauty are matched only by her skills as a spearwoman, which she shows off to marvelous effect in the sequence in the casino. Disguised in a vermillion gown and an uncomfortable wig—which she snatches off and tosses into an adversary’s face, turning feminine distraction literal—Okoye stabs and throws and pulls her spear from corpses with graceful panache. In a subsequent car chase, as her assailants shoot at the vehicle she’s in, Okoye sums up the traditional Wakandan hierarchy of weapons: “Guns,” she rolls her eyes. “So primitive.” It’s a clear riposte to Klaue, the film’s token bad white guy, who says he steals vibranium from Wakandans because “you savages don’t deserve it.” It’s no accident that “vibranium” contains the word “brain”—the secluded Wakanda, never colonized, is secretly the most advanced country in the world, under the cover of being a “nation of farmers.”

Black Panther’s speculative fantasy does not simply reverse these stereotypes about Africa; it complicates them. We see plenty of Wakandan weaponry that might be considered “primitive” or “savage”: swords, daggers, scimitars, shields, and even beasts—trained, armored rhinoceroses that seem part horse, part tank. Central to Wakandan rites of succession is a ceremony of hand-to-hand combat, in which warriors from the various tribes in the country challenge T’Challa for the throne. The film stages two of these gladiatorial battles on the very edge of the Warrior Waterfalls—a deathly gorge below, a mountainous amphitheater above. Before the fight begins, the heir to the throne must drink a potion that strips him of the power of the Black Panther—a physical power that comes, like a natural steroid, from a vibranium-infused plant called the Heart-Shaped Herb, which is cultivated by the Wakandan royal court. Given only wood and metal weapons and his bare hands to fight with, he is reduced from a demigod to a mere mortal, or more precisely, to a man.

Advertisement

All but one of T’Challa’s challengers are male, as would be expected for a rite of passage revolving around brute strength. The kingdom seems to be based on bloodlines—only tribal royals are allowed to challenge the throne, and at no point is a woman seriously considered as a possible candidate for the monarchy. There is a hint otherwise when the battle is thrown open to any last challengers: T’Challa’s younger sister, Princess Shuri (Letitia Wright), raises her hand. Indeed, in the comic, Shuri actually wants to challenge her brother for the throne and (potential sequel spoiler) she later takes his place when he’s in a coma. But in the film, we get a quip about an uncomfortable corset instead, as if to deflect the obvious phallocentrism of the Wakandan monarchy.

The joke is funny, though, and suits Shuri’s personality: she is the techno-genius of Wakanda, a brilliant teen whiz who, as one challenger puts it, “scoffs at tradition.” Wright, clad in mesh hiphop gear, is a sheer delight in the wise-cracking role, and she stands in for the innovative side of Wakandan weaponry. She relishes demonstrating “updated” gadgets to her brother (“just because something works, does not mean it cannot be improved”), which range from Kimoyo Beads, used for medical and communication purposes, to a gleaming black suit that materializes from a metal necklace and spreads over the body at a moment’s notice. Later in the film, we see other neat futuristic devices that merge the rudimentary with the digital in the name of defense: “gauntlet” boxing gloves, spinning “ring blades,” and even Basotho blankets that turn into force-field shields.

The substrate of all these weapons is vibranium itself, which in the Marvel Universe is the strongest metal on earth (Captain America’s shield contains some) and, at the same time, has a curious—and symbolically rich—property: it can absorb, store, and disperse kinetic energy. As Shuri explains, T’Challa’s suit collects the force of every whack it withstands, holding it in place “for redistribution.” It takes bullets, blows, and bombs—which charge it with energy that he then booms back out into the world. Vibranium has the potential to be a new energy source, to soak up nuclear fallout, to mitigate climate change. In Black Panther, it’s mostly just a weapon, and a MacGuffin—the thing everyone wants that triggers the action.

But as a metaphor, vibranium also taps a cluster of black tropes, including the longstanding theme of “vibration” in Afrofuturist art and the historical gutting of Africa’s mineral resources. Its capacity for “redistribution” can be allegorized politically, but in two opposed ways that comprise the main conflict of the plot. Should Wakanda share vibranium as a technology, redistribute it as a resource to oppressed people around the world? Or should Wakanda share vibranium as a weapon for retributive justice, eye-for-an-eye, tooth-for-a-tooth, by any means necessary?

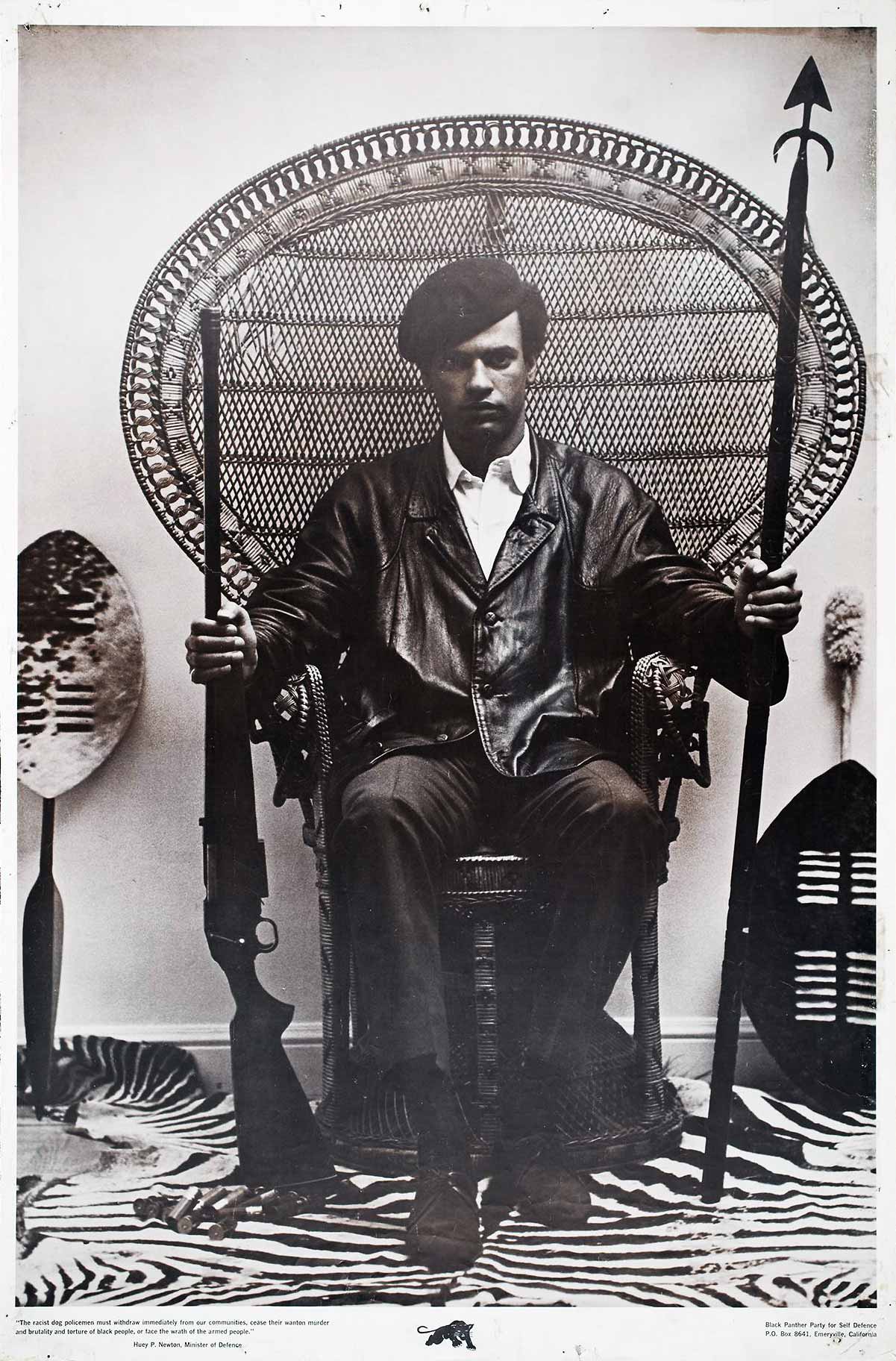

This last phrase, made famous by Malcom X, is never uttered in Black Panther. But it hovers over the film—and its marketing—as the verbal equivalent of one of the most potent visual symbols of the Black Power movement. Black berets, black afros, black leather jackets, and big, black guns: that’s how we recognize the Black Panther Party, which was formed just months after Stan Lee and Jack Kirby named their new comic book hero thus. Huey P. Newton, who took the name and the mascot from the Lowndes County Freedom Organization, said it was a fitting symbol because a panther doesn’t strike first, “but if the aggressor strikes first, then he’ll attack.” This reasoning, uncannily like a description of vibranium, did nothing to change the widespread view that the Black Panthers were themselves the aggressors. In fact, the retaliatory logic of the Panthers turned the legacy of American violence back on itself—the Second Amendment right to bear arms included.

The true antagonist of the film, Erik Killmonger, in a luminous—no, numinous—performance by Michael B. Jordan, is a Black Panther of the American sort. He speaks a pithy, cutting black vernacular, he likes his guns, and he comes from Oakland, California. We learn that he is African American in the most literal sense—the son of a black American woman and a Wakandan royal, N’Jobu, who was radicalized by the suffering he saw among black people in America. When N’Jobu sold vibranium arms to facilitate revolution, his brother King T’Chaka killed him; Killmonger vows to avenge his father’s death by killing T’Challa.

Advertisement

As violent and vengeful as he is made out to be, Killmonger has as much claim to the title—of the film and as the King—as T’Challa does. Like Milton’s Satan, this villain steals the limelight: Killmonger is a fallen son and a traitorous ally—and a charismatic revolutionary, to boot. After he beats T’Challa and wins the throne, he declares his aim to arm the masses across the world so that they can “rise up against their oppressors,” finally granted the firepower and resources they have historically lacked. This mentality is apparently abhorrent to the Wakandans, who cry, “That is not our way.”

But I kept wondering: what is the Wakandan way, exactly? T’Challa chides Killmonger for becoming like his enemies and protests that Wakandans will never serve as “judge, jury, and executioner to people who are not our own.” Yet T’Challa comes very close to doing just that to both Klaue and Killmonger. An abandoned son, “a monster of [their] own creation,” Killmonger forces Wakandans to confront their reliance on the very structures that led to his rise to power—all the ones that implicate each other: masculinity, power, violence, capital.

Beyond the fictional world of the movie, a new and worthy initiative called Wakanda the Vote is registering audience members to vote in the next US elections. But, like Thor’s Asgard, and unlike most African countries, the mythic Wakanda is not an electoral democracy. It is a bloodline-based monarchy backed by a wrestling match with the logic of a ritualized coup d’état. At one point, Nakia says tearfully, “The King is dead,” and you can almost hear the standard response, “Long live the King”—instead, Killmonger later declares, “I’m the King now.” And he is correct—that is precisely what a political process built on physical prowess would yield. Might isn’t always right.

In Shuri’s terms, Wakanda needs an “update.” The nation may have escaped the ravages of imperialism, but not its logics of partition and power. Indeed, Wakanda bears a strong resemblance to the nation against which its “culture” is most explicitly pitched: the United States of America. The characteristics the nations seem to share include: isolationism (weaponized defense against outsiders); blood logic (eugenics-tinged social hierarchies and nepotism); violence (hand-to-hand combat and a propensity for civil war); and capitalism (we see a Wakandan marketplace where fried meats, woven baskets, and old tech are sold).

Killmonger is not just a lost Wakandan son or a murderous gangbanger; he is also a Special Ops Navy Seal with an MIT degree and training in disrupting foreign governments during transfers of power. He outlines his mercenary résumé: “I’ve killed in America, Afghanistan, Iraq… I took life from my own brothers and sisters right here on this continent!” Every kill he has sold (a monger is a seller) has presumably been executed with a firearm. As if in imitation of the bullets he’s embedded in others, he decorates his torso and arms with little round scars. They have an “African” look to them. They could be beads or a mancala game or leopard’s spots or just scars—cicatrization is a common form of body modification across the continent. But they also reminded me of branding and tabulation charts, that is, the weaponry of the transatlantic slave trade.

The slave trade is the heartbreak at the core of the film, the unhealable wound, the schism between Africa and America. Killmonger’s longing to bridge that gap glows off him. The way he says “hey auntie” and “wass up” and even “princess” to his Wakandan relatives teeters on the line between ironic distance and genuine homesickness. His final battle with T’Challa takes place in a kind of high-tech Underground Railroad, an inversion of the bare-hands brawls at Warrior Falls. Before Killmonger drives a blade deeper into his own chest, he asks to be buried “in the ocean with my ancestors that jumped from the ship because they knew death was better than bondage.”

Killmonger is riddled with murder in both senses. One of Coogler’s magnificent accomplishments as a director is that, at times, when we look at Erik Killmonger, we see Oscar Grant. The scars on one black man’s body are the bullet holes in the other’s. Just before Killmonger makes his request to join the corpses lining the bed of the Atlantic, T’Challa makes a final offer: “Maybe we can still heal you.” Killmonger replies: “Why? So you can just lock me up?” I longed in that moment for Chadwick Boseman to give us one of his subtle frowns and say: “Oh, we don’t have prisons in Wakanda.” After all, one of the most famous prison abolitionists in the world, Angela Davis, was once a Black Panther. But that would be a “what if…?” too far for an American comic-book franchise.

After Killmonger’s anguished death, it seems a weak gesture for T’Challa to set up a neighborhood outreach program in the Oakland apartments where his father murdered his uncle. This conclusion taps the roots of the Black Panther Party’s community programs, but it chooses respectability over revolution, donations over decolonization. The Wakandan Outreach Center offers a toothless, or perhaps declawed, ideology, built on gentrification (will there be outreach for the ousted tenants?) and the vaguest liberal cant: “social outreach” and “science and information exchange.” In a post-credits sequence, we see T’Challa announcing to a sort of United Nations, under the watchful eye of the CIA, that Wakanda will now share its technology with the rest of us.

The Wakandan technology I would want to get my hands on is both the most cutting-edge and the most subtle; Shuri simply refers to it as her “sand pit.” Like an Afrofuturist iteration of 3D printing, a black sand (perhaps granular vibranium) coalesces into inhabitable shapes—a car, a plane—that remotely navigate real vehicles. (Fittingly, the token good white guy, a CIA agent, pilots a drone-like one to bomb other fighter planes.) At one point, armor appears to grow out of Shuri’s sand pit. At another, black sand seems to be the basis for 3D video calls, creating a sculptural hologram of the person you’re speaking to in the palm of your hand. The opening sequence of the film, in which we learn the founding myth of Wakanda, uses an analogous form of graphic animation. Shimmering black grains rise and fall from a bed of volcanic sand to form transient pointillist figures and architecture. Adaptive, improvisational, and interactive, black sand mediates between nature and tech, the ancient and the futuristic, the simple and the complex, the individual and the collective.

It is an apt figure for Black Panther’s aesthetic. Movies often flatten real African cultures into two-dimensional imagery—stereotypes in stereo, a quilt of clichés. But Wakanda, as everyone keeps reminding us, doesn’t exist. This gave Ryan Coogler free rein to create a country in the subjunctive mode: what if…? Given a blank canvas, he chose to sculpt and embroider various materials, genres, and tones. Black Panther is Shakespeare meets Shaka Zulu, Too $hort in Timbuktu. The film mingles myriad cultures, fashions, geographies, and (a quibble) accents from across the black diaspora. But even my skepticism about the casting of non-Africans fell away in the face of this glorious Pan-African cornucopia: actors with heritage from Guyana, Zimbabwe, Kenya, Uganda, Nigeria, South Africa, Côte d’Ivoire, the US, and the UK. Audience reactions have been equally diverse, not only in location but also in feeling—the critical debates as lively as the joy. The politics of representation in Black Panther’s diasporic casting and audience may be more powerful, in the end, than its shortcomings in theorizing a truly representative democracy.

In this sense, Wakanda’s black sand is more than a cool visual effect and a gorgeous syncretic aesthetic—it expresses an ethos. Metaphorically speaking, it is a kind of black matter—infinite potential, infinite power—or a crowd of black bits that gather and disperse, that allow us to inhabit others’ experiences, that take on different colors and form a multicultural mosaic, that distribute and redistribute energy among the many. Rather than reflecting or distorting a world, this technology builds a world… and then lets it fall away. I cannot think of a better metaphor than black sand for a diaspora, a word that comes from a “scattering” yet has come to signify unity and solidarity.

How long before Marvel further weaponizes and monetizes it? I’m not hopeful. As this last week in the US has shown—this last month, year, decade—we still live in a culture where masculinity, power, violence, and capital hold hands, hold sway, and hold us hostage. Weapons may be metaphors. But weapons are also just weapons.

Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther is now in theaters.