Not long after their arrival to the United States, the Bauhaus instructors Josef and Anni Albers went looking for America and found it… in Mexico.

Driven from Germany when the Nazis closed the Bauhaus in 1933, the Alberses accepted invitations to teach at Black Mountain College in North Carolina; beginning in 1935 and over the next thirty-two years, they made some fourteen road trips to Mexico, visiting, revisiting, and documenting pre-Columbian ruins at Monte Albán, Mitla, and Uxmal among other sites, some of which were in the process of excavation, while also taking note of traditional adobe buildings.

Tucked into the Guggenheim Museum’s tower gallery on the fourth floor, the exhibition “Josef Albers in Mexico” makes Albers’s appreciation evident, juxtaposing his studies, typically drawn on graph paper, with both his finished artwork (mostly paintings, one lithograph) and his fastidious arrangements of tiny on-site photographs. Serially organized in irregular grids, and sometimes including picture postcards, these photo-collages (never previously exhibited) appear to be Albers’s means of assimilating what he saw. By breaking down architecture and façades into basic patterns, they also provide a way to analyze his art. (In her contribution to the exhibition catalog, the show’s curator, Lauren Hinkson, suggests that “the iterative logic of the camera” may have been as influential as the buildings themselves.)

The show’s pedagogical aspect is appropriate, given Albers’s distinguished career as a teacher at the Bauhaus, at Black Mountain (where students included Robert Rauschenberg, Ray Johnson, and Cy Twombly), and finally at Yale (where the eccentric minimalist Eva Hesse and the psychedelic poster artist Victor Moscoso were star pupils). But the work here is also very beautiful—not least in its economy. Frugality was part of the Albers aesthetic. The modestly-sized works have ample room to breathe.

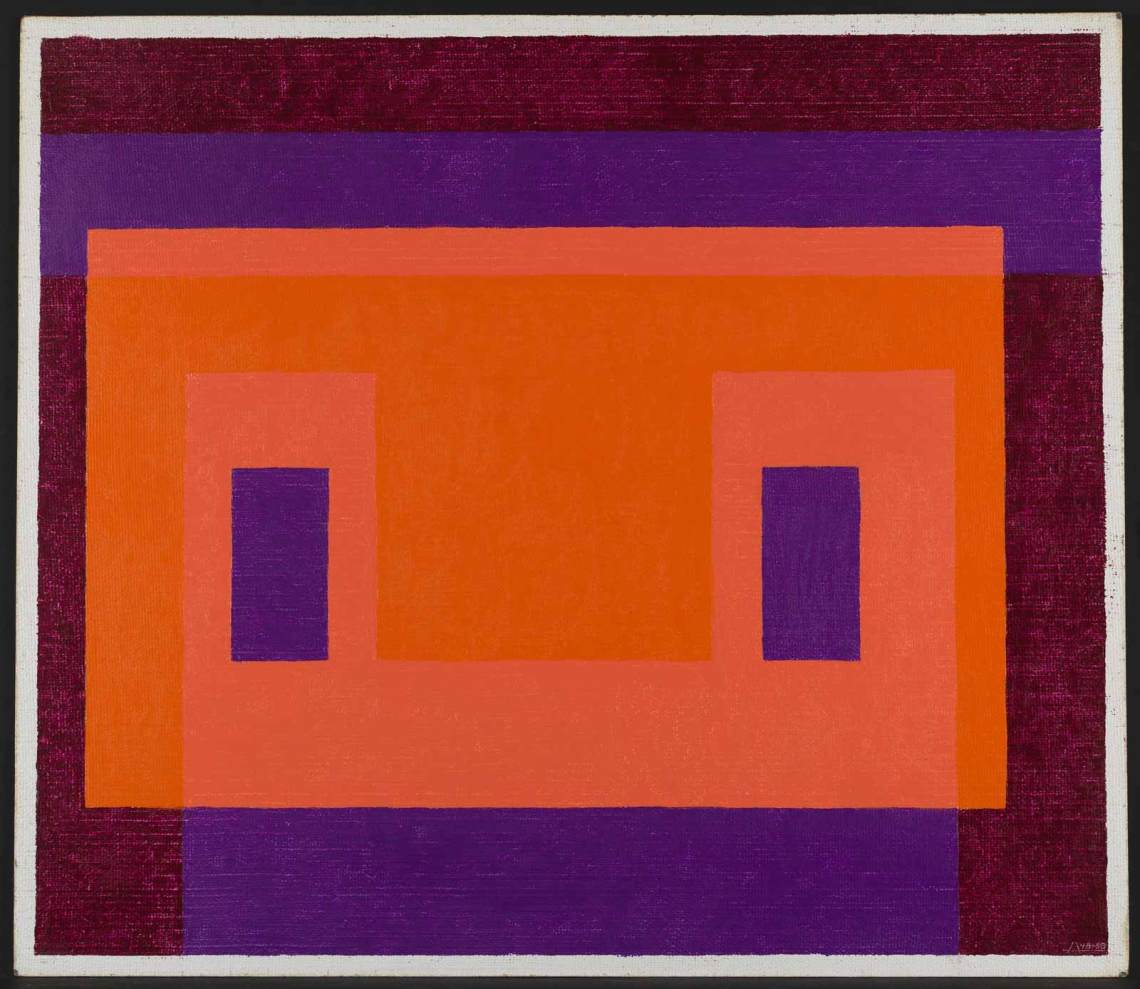

The welcoming view of the subtly four-colored Variant/Adobe, Orange Front (1948–1958) has a checkerboard structure seemingly inspired by the window-in-wall architecture of Mexican pueblos. (It also suggests an architectural drawing of two pyramids from an aerial perspective, and was a form sometimes seen on Mexican rugs.) Made between 1946 and 1966, using a set range of compositions and formal elements, the 250 Variant/Adobe paintings and drawings presage Albers’s larger and better-known Homage to the Square works, which, according to some, also arose from an interest in vernacular adobe façades.

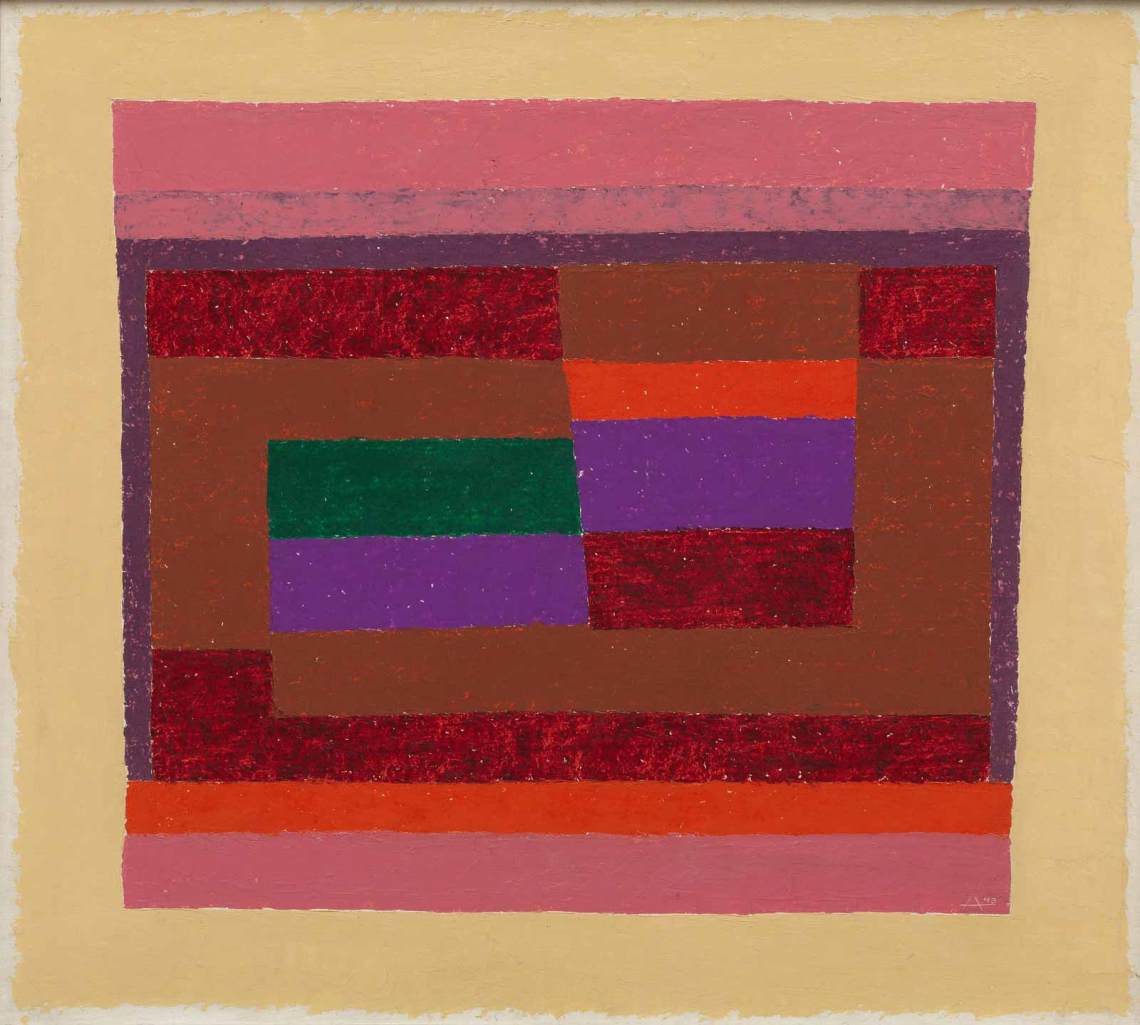

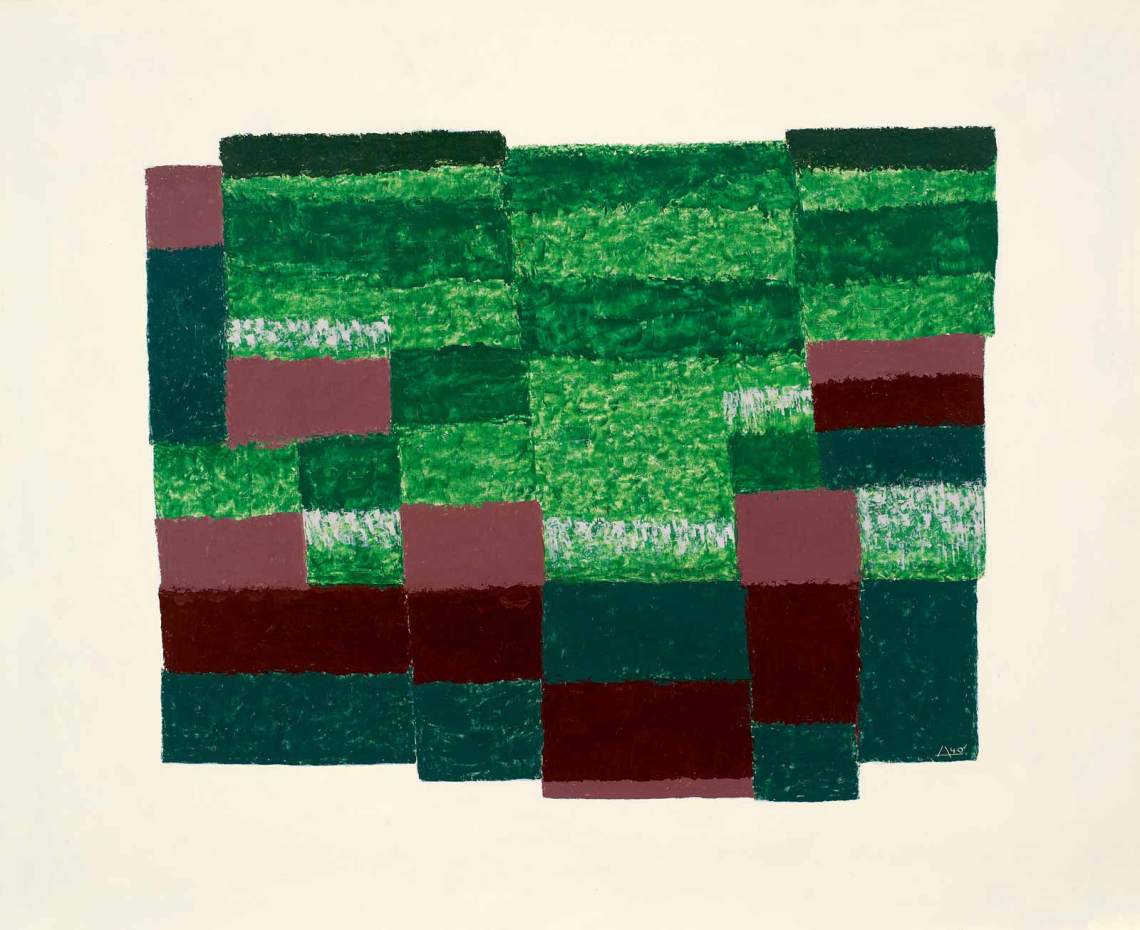

Some Viriant/Adobe paintings are austerely festive. The deep green, rich brown patchwork of Tierra Verde (1940) evokes the Mexican landscape as it might appear from a great height. The same year’s To Mitla is an amazingly gemütlich crypto-pueblo that—with a cluster of deep red, maroon, and purple rectangles clustered between a baby blue “sky” and the chartreuse earth—would be colorful even by Mexican standards. Adding hot pink to Albers’s palette, Memento (1943) is still more vibrant.

Albers’s photographs of carved stone façades and symmetrical courtyards pay homage less to the square than to the genius of Mayan or Zapotec engineering—as well as the power of strong diagonals. Mexico provided Albers with an alternate classical tradition. The show includes several rigorous line studies clearly inspired by the ziggurats of Monte Albán and Chichén Itzá. Compared to his best-known work, Albers’s early geometric abstractions and many of the Mexican paintings are distinctly free-form (some, from the 1930s, might be described as jazzy), and are frequently concerned with the representation of three-dimensional space. By 1950, Albers is concentrating almost entirely on flatness, rectangles, and the interaction of different colors.

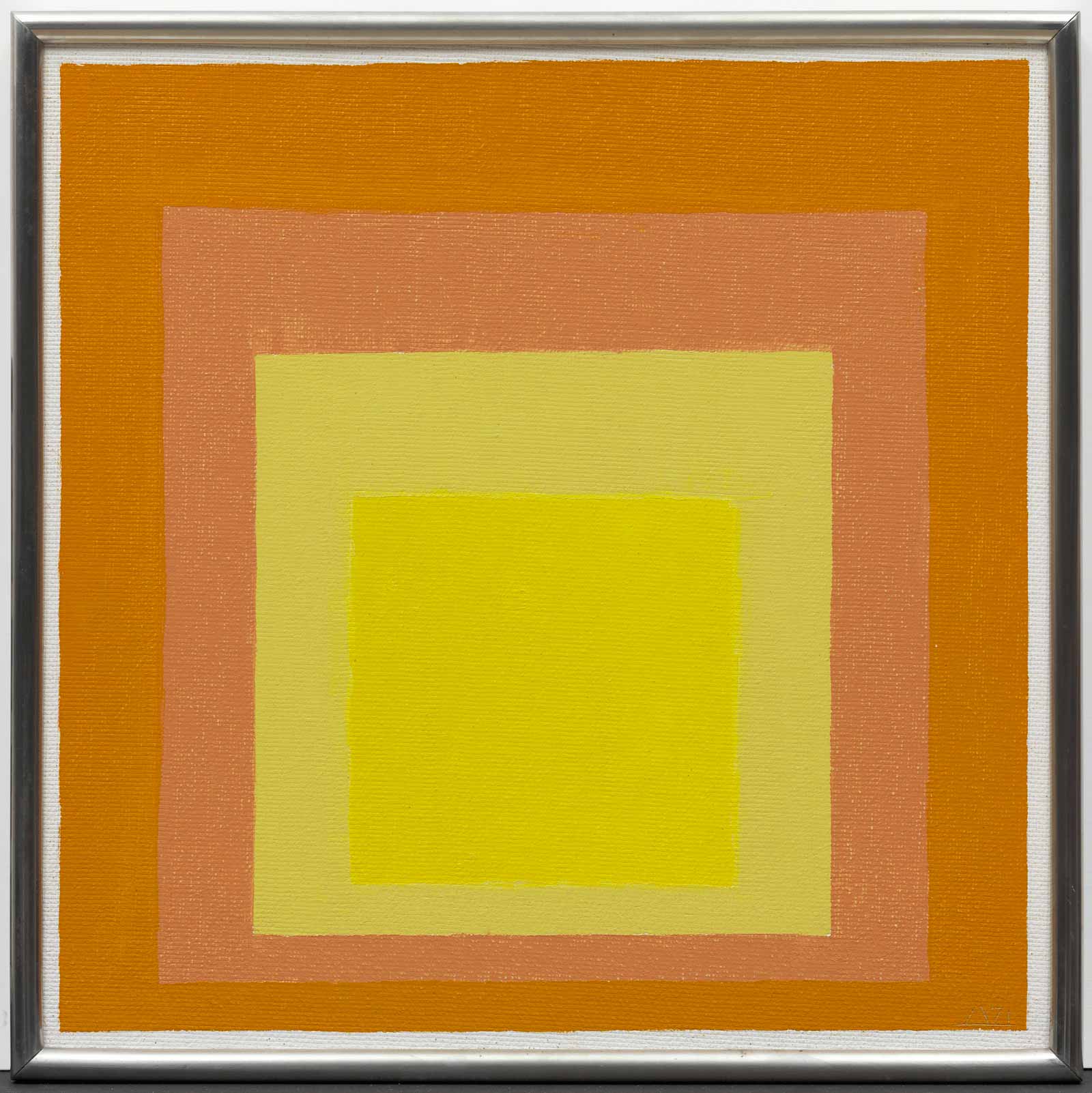

Albers’s oil on Masonite paintings, whose dimensions rarely exceed (or even reach) two feet by two feet, are both arrogant and unassuming in their simplicity. As anti-expressive as they are, the artist’s hand is nonetheless detectable; some contemporaries, like the hyper-fastidious minimalist Donald Judd, otherwise one of Albers’s champions, found them “slightly too loose and painterly.” Others considered them inconsequential, as Harold Rosenberg appeared to suggest in a Partisan Review interview with the sociologist Melvin Tumin, in which he compared Albers’s aims with those of Barnett Newman. Allowing that both men were excellent painters, Rosenberg explained that the heroic Newman “is involved with the question of the absolute in relation to man,” while Albers, perhaps too corny for Rosenberg to take altogether seriously, “is involved with color relations.” (Albers, who saw his art as “spiritual creation,” once sent word to Rosenberg that angst was overrated.)

Advertisement

Newman, whose most confrontational work (even inspiring physical defacement) is the series of four large-scale paintings titled “Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue,” sought to produce awe-inspiring icons. With some 2,000 versions of Homage to the Square, Albers mass-produced by artisanal means modest objects of contemplation that are closer to mandalas (which is perhaps how his disciple Moscoso came to see them) than paintings. I would like to think that, as well as working on what seemed to him an inexhaustible set of circumscribed variables, Albers was inspired by American democracy and a utopian belief that everybody might have an Homage to ponder on the wall. (In fact, Albers’s squares were imitated as a panel design for mid-Sixties dress fabrics, but that’s another story.)

It’s touching to find one of the Albers’ Pemex Road maps of Mexico in a vitrine, alongside a guidebook and some of the postcards they sent to friends. And as invigorating as it is to see a half-dozen iterations of Homage to the Square occupying one gallery of “Josef Albers in Mexico,” it is disconcerting that the Guggenheim show omits any trace of Anni Albers (aside from a few photographs of her), even though she accompanied her husband on every one of his trips to Mexico and produced work that, like his, was clearly inspired by what they saw.

A weaver rather than a painter, Anni Albers was an established artist in her own right with a solo show at MoMA in 1949; and her work is elsewhere currently enjoying a revival of interest—in his New Art City, Jed Perl describes her as “the greatest weaver of the [twentieth] century.” It’s confounding, then, not to see even the one example of her “pictorial weaving” reproduced in the exhibition catalog. It seems improbable that the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation would have wished to withhold her work. In the absence of any explanation, her erasure from this otherwise magnificent show smacks of sexism, or snobbery, or both.

“Josef Albers in Mexico” is at the Guggenheim through April 4.