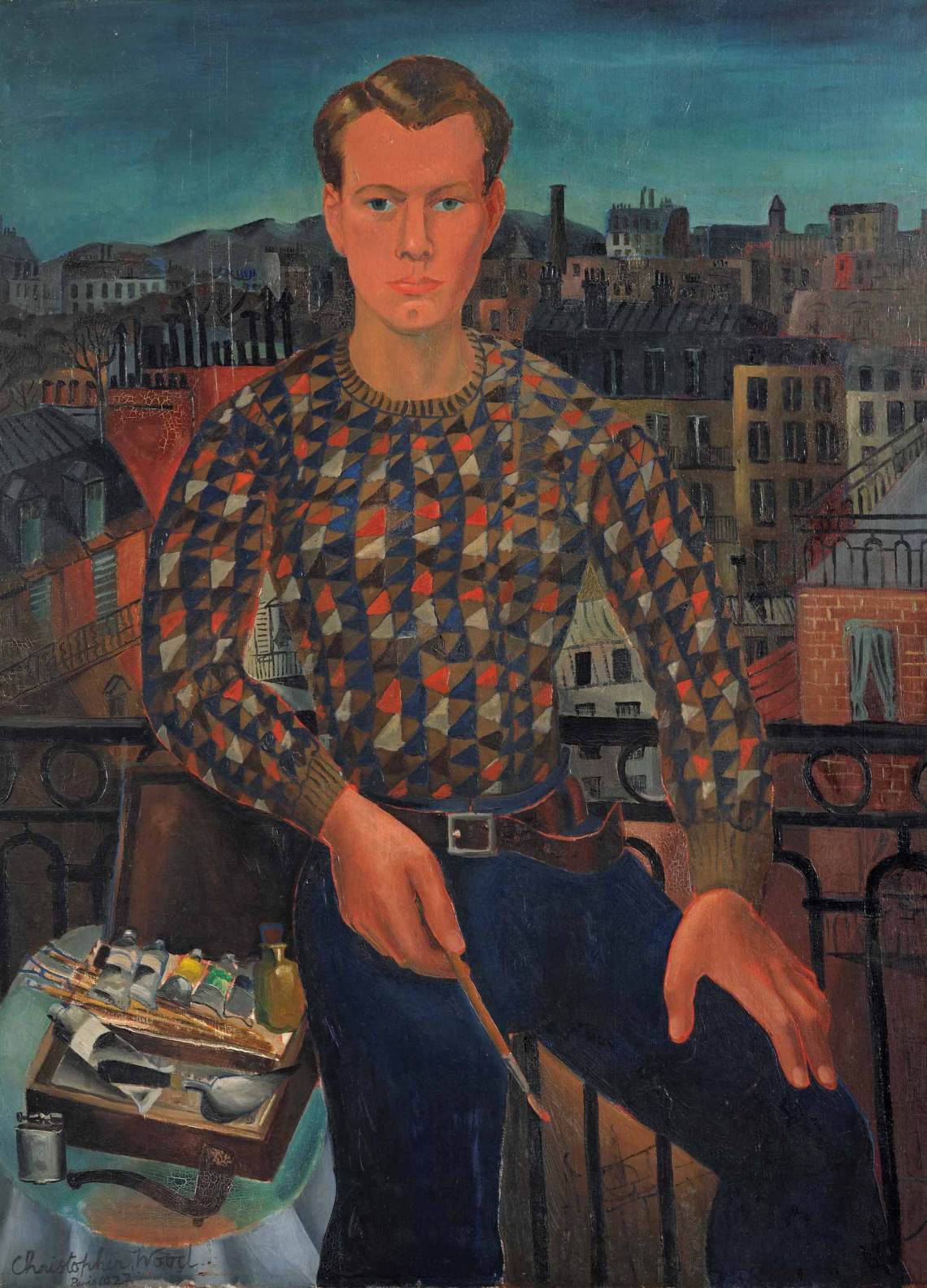

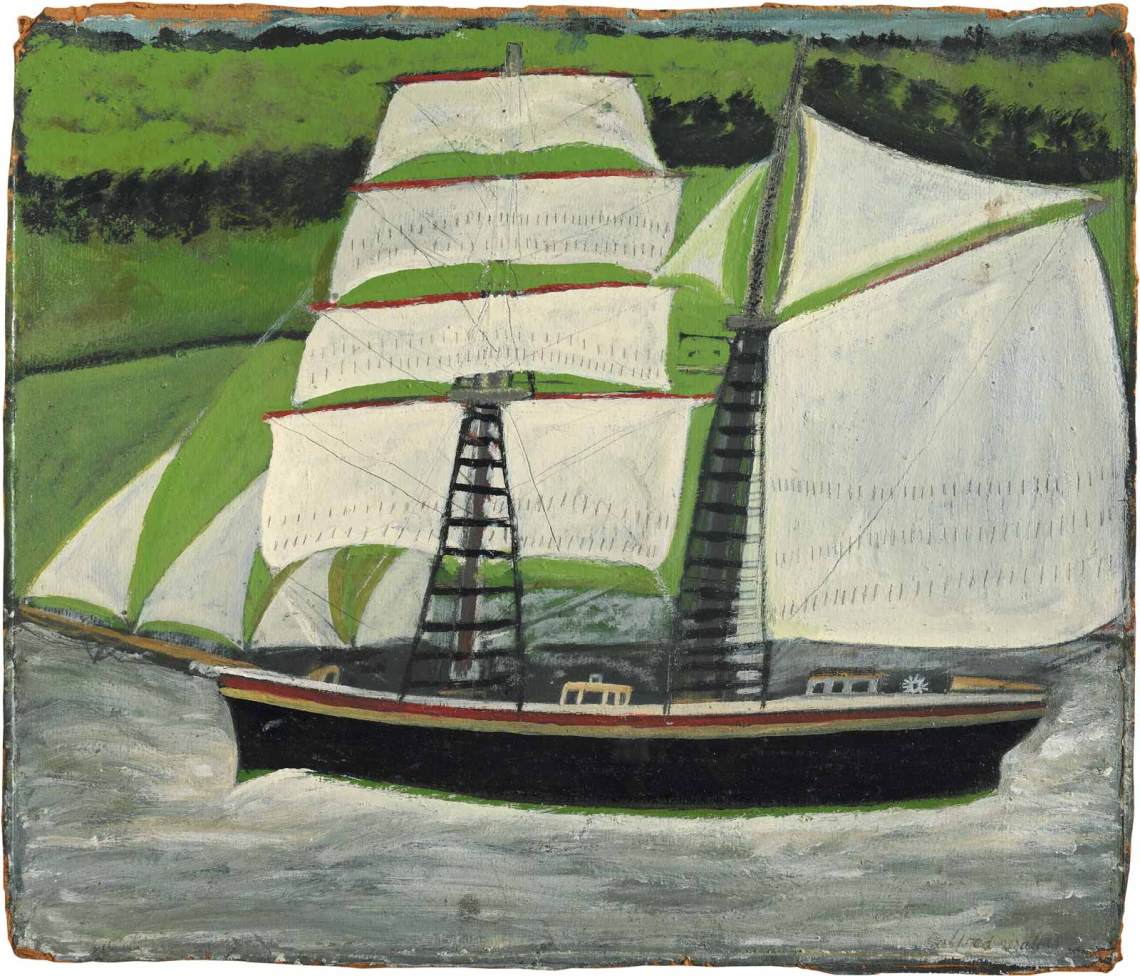

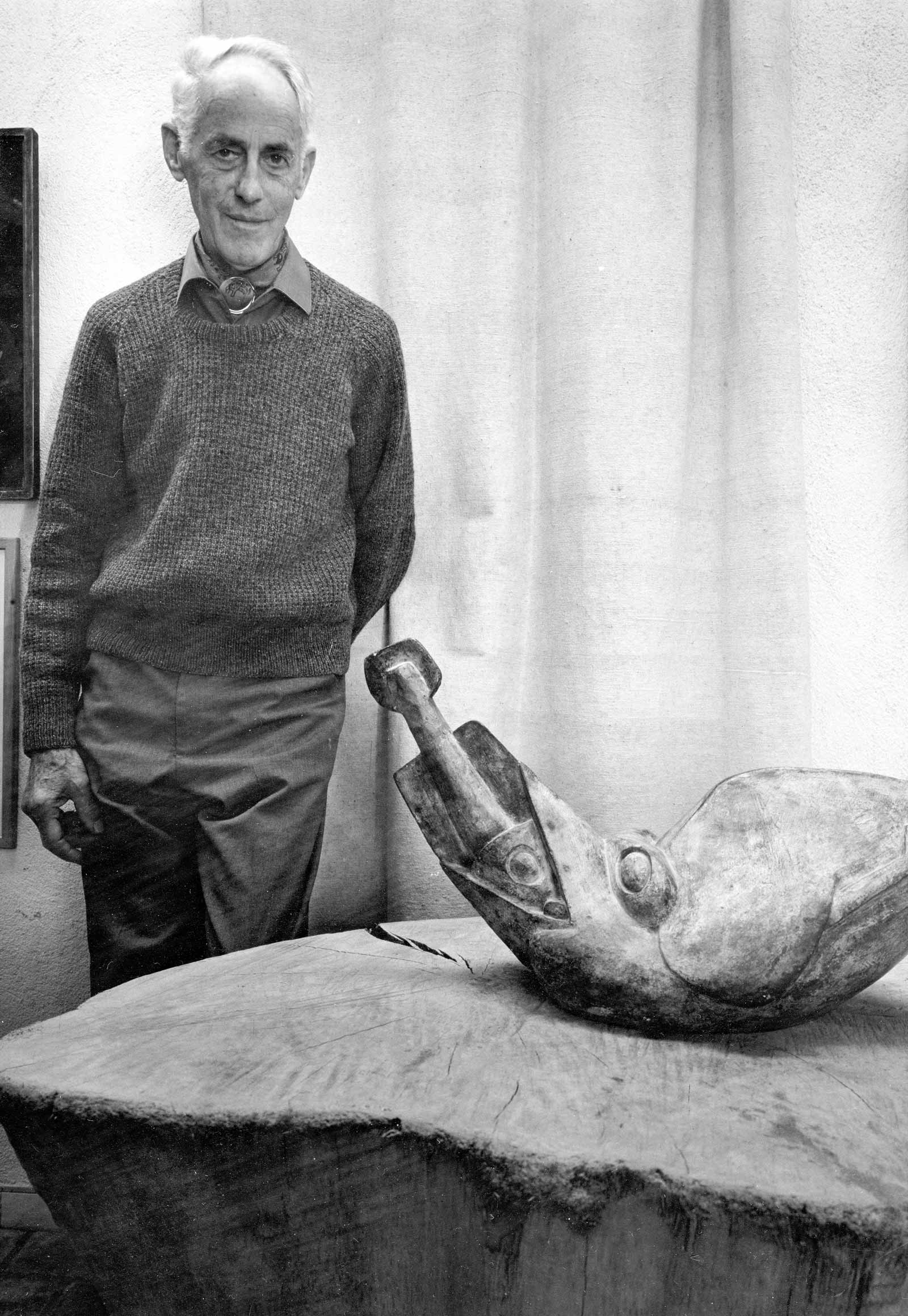

In the mid-1950s, having amassed an impressive private collection of contemporary art, Jim Ede—who began purchasing during his stint as a curator at the Tate in the 1920s and 1930s—was looking for somewhere to display his spoils. He began by buying the works of painters he knew: Ben Nicholson, Christopher Wood, and David Jones. Alfred Wallis famously used to send Ede paintings in bulk by post, sometimes as many as sixty at a time, price fixed according to size, from which Ede could choose the ones he wanted. To these were added works by Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Constantin Brancusi, Barbara Hepworth, and Henry Moore among many others. Ede had no interest in a traditional gallery space but instead envisaged “a living place where works of art would be enjoyed, inherent to the domestic setting, where young people could be at home unhampered by the greater austerity of the museum or public art gallery, and where an informality might infuse an underlying formality.”

Kettle’s Yard, four old slum cottages, tucked away behind St. Peter’s Church in Cambridge (named after the Kettle family, who had built a short-lived theatre on the site back in the 1700s), became the location of Ede’s experimental vision. He renovated them and unpacked his collection, around which he and his wife, Helen, set up home, thenceforth holding an “open house” every afternoon during the university term, when students were encouraged to drop by, admire the art, read the Edes’ books—and, if lucky enough to be invited, perhaps partake of a cup of tea and a slice of toast with marmalade. Part of the charm of Kettle’s Yard has always been the juxtaposition between old and new. The exterior of the row-houses was preserved as part of the renovation, and while certain original fixtures remained inside—the brick fireplaces, for example, and the hefty wooden beams supporting the ceilings—around these the Edes created a distinctly midcentury modern space.

The couple made this their home for over fifteen years, during which time their regular open houses were accompanied by music performances, expanding over time to include chamber concerts, contemporary music, and student recitals. In 1966, the Edes handed over Kettle’s Yard to the University of Cambridge, though they continued to live there, Ede in the role of “honorary curator.” When, seven years later, in 1973, the responsibilities involved became too great—Ede was then in his mid-seventies, and Helen’s ill health became increasingly problematic—the Edes relocated to Edinburgh (Helen’s home town and where they’d first met, at art school), officially bequeathing the house to the university.

Having reopened in early February of this year after closing for about two years for extensive renovation, the arrangement at Kettle’s Yard today is a little more institutionalized than during its heyday. Entry is free, but it’s organized by timed ticket, which can only be purchased in person and on the day of the visit (a limited number of tickets will soon be available to book in advance online). All the same, the current director, Andrew Nairne, clearly hasn’t lost sight of Ede’s original vision. There’s no tea or toast (unless you pay for it in the newly installed café), but you are invited to get up-close and personal with the collection (within reason, of course). You can take a seat in any of the myriad chairs dotted throughout the house to better admire your surroundings—plenty of pictures have been hung at seated eye level so as to encourage such lingering—and the library boasts a vast wooden table for easy perusal of the Edes’ book collection.

Such freedom seems less than advisable when you’re ushered into the first, rather pokey low-ceilinged ground-floor rooms, but ascend to the first floor and it’s a different story. A roomy, light-filled space opens out, leading seamlessly into what was the first of the house’s extensions, added in 1970 and designed by Sir Leslie Martin, then head of the architecture school at the University of Cambridge and co-designer of London’s Royal Festival Hall (the architectural history of Kettle’s Yard is as impressive as the collection housed there). An additional gallery space was also added at the same time, itself enlarged on multiple occasions over the course of the following two decades, and it’s this, rather than the house itself, that has been the subject of the latest overhaul.

Advertisement

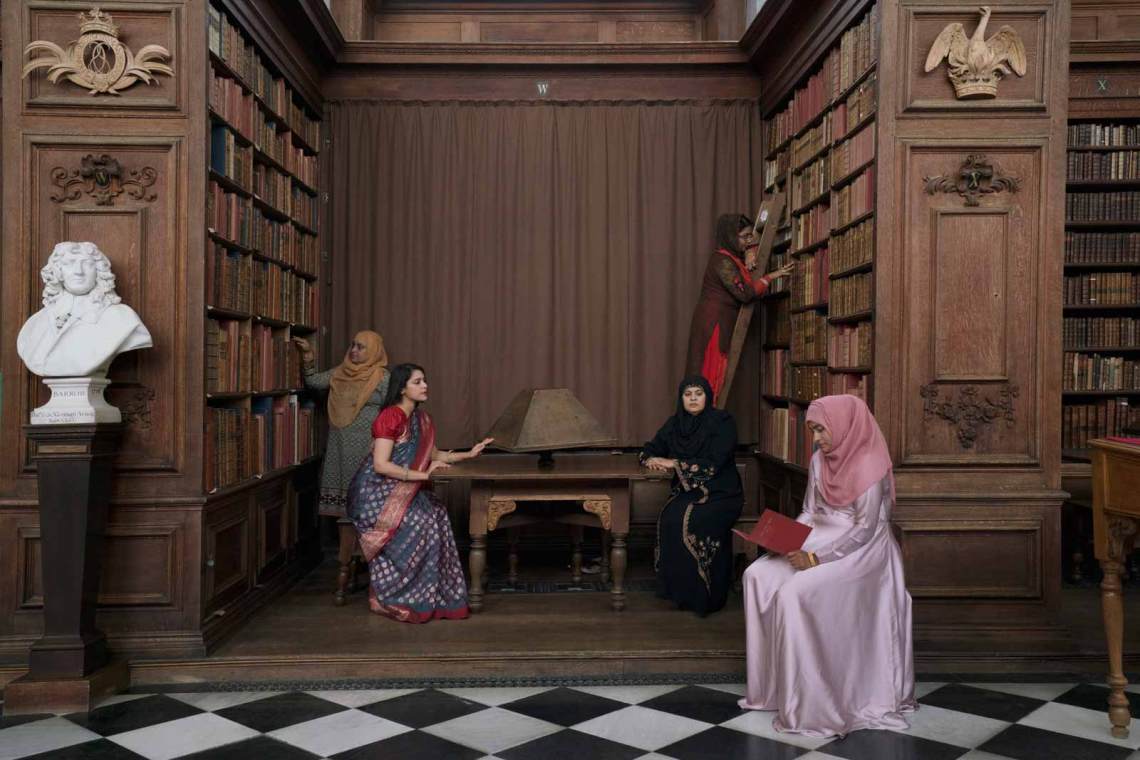

Now, in addition to the original house, visitors also enjoy a new separate education wing and gallery space, currently housing an exhibition that collects the works of thirty-eight contemporary artists, called “Actions. The image of the world can be different,” which emphasizes art’s capacity as a social and political force. There’s also a new open-plan entrance area, shop, and café, all of which is elegant and inviting, but not particularly noteworthy—especially next-door to Ede’s extraordinary creation. The gallery and education wing’s generic concrete floors, vast white walls, and steel-lined staircases could belong to any contemporary UK institution, which is perhaps unsurprising given that it’s the work of Canadian-born architect Jamie Fobert, best-known for the recent extension at Tate St. Ives.

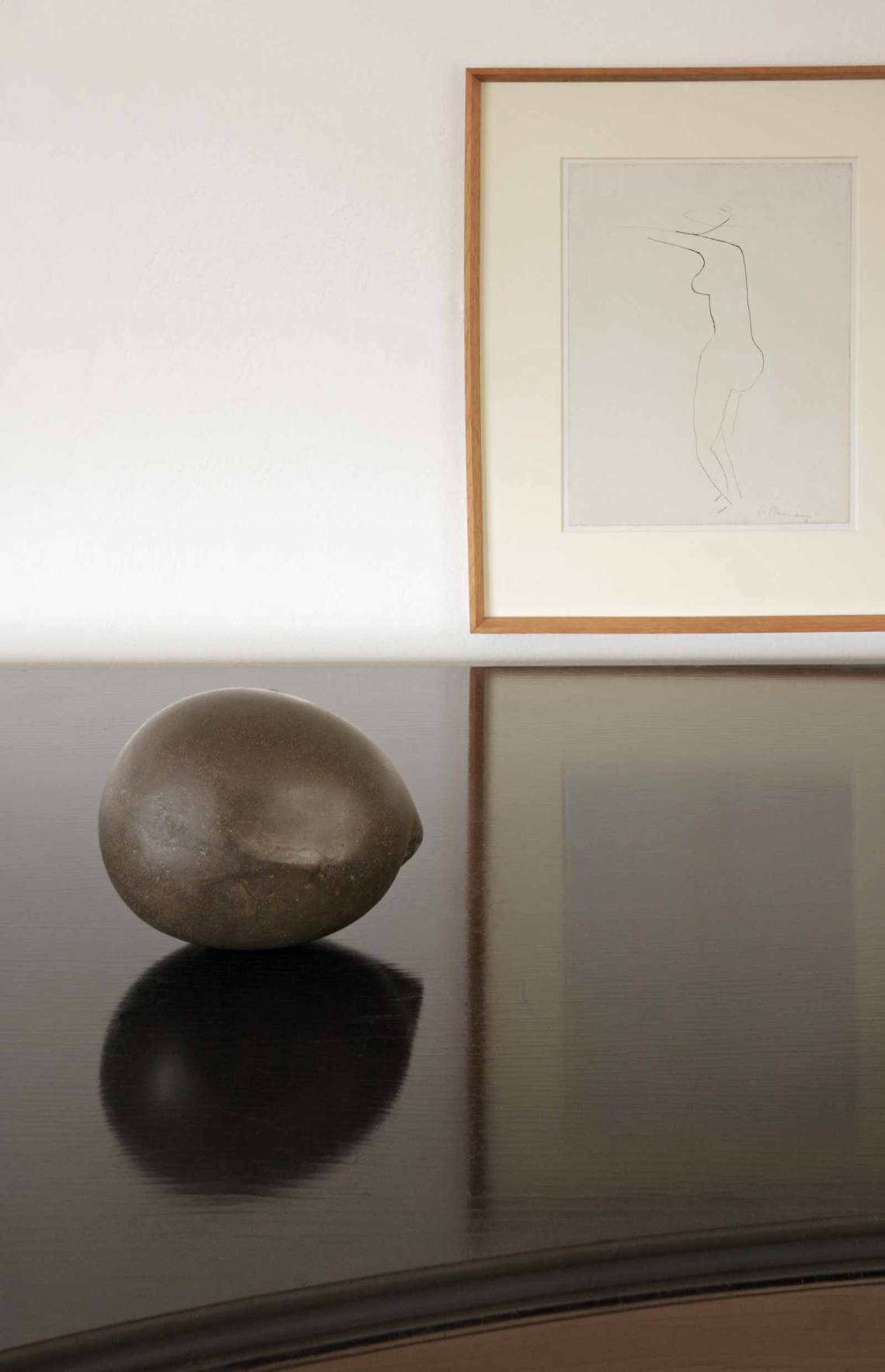

The success of the Edes’ unique vision lies in part with the carefully contrived unobtrusiveness of their curation. Consider this snapshot of the sitting and dining room: among the Alfred Wallises, David Joneses, and Christopher Woods hung about the walls, the whorl of a delicate spiral of pebbles precisely arranged on the low wooden table in the window alcove is reflected in the corkscrewed grooves of the large, dark-stained wooden cider press screw that stands on the other side of the room, the same motif then repeated in the spiral staircase, glimpsed through the doorway in the hall, that ascends to the Bechstein Room above.

Thankfully, a similar attention to detail has been taken with the curation of “Actions.” The thoughtful positioning of a few select works beyond the four walls of the new gallery establishes a sense of continuity between the museum’s history and its present. Sculptor and installation artist Cornelia Parker has adorned the window panes of Helen’s bedroom with streaks—of rain, or of tears?—drawn with chalk from the white cliffs of Dover. In the downstairs extension, an arrangement of ceramicist Edmund de Waal’s porcelain pays homage to Ede’s own carefully placed pieces.

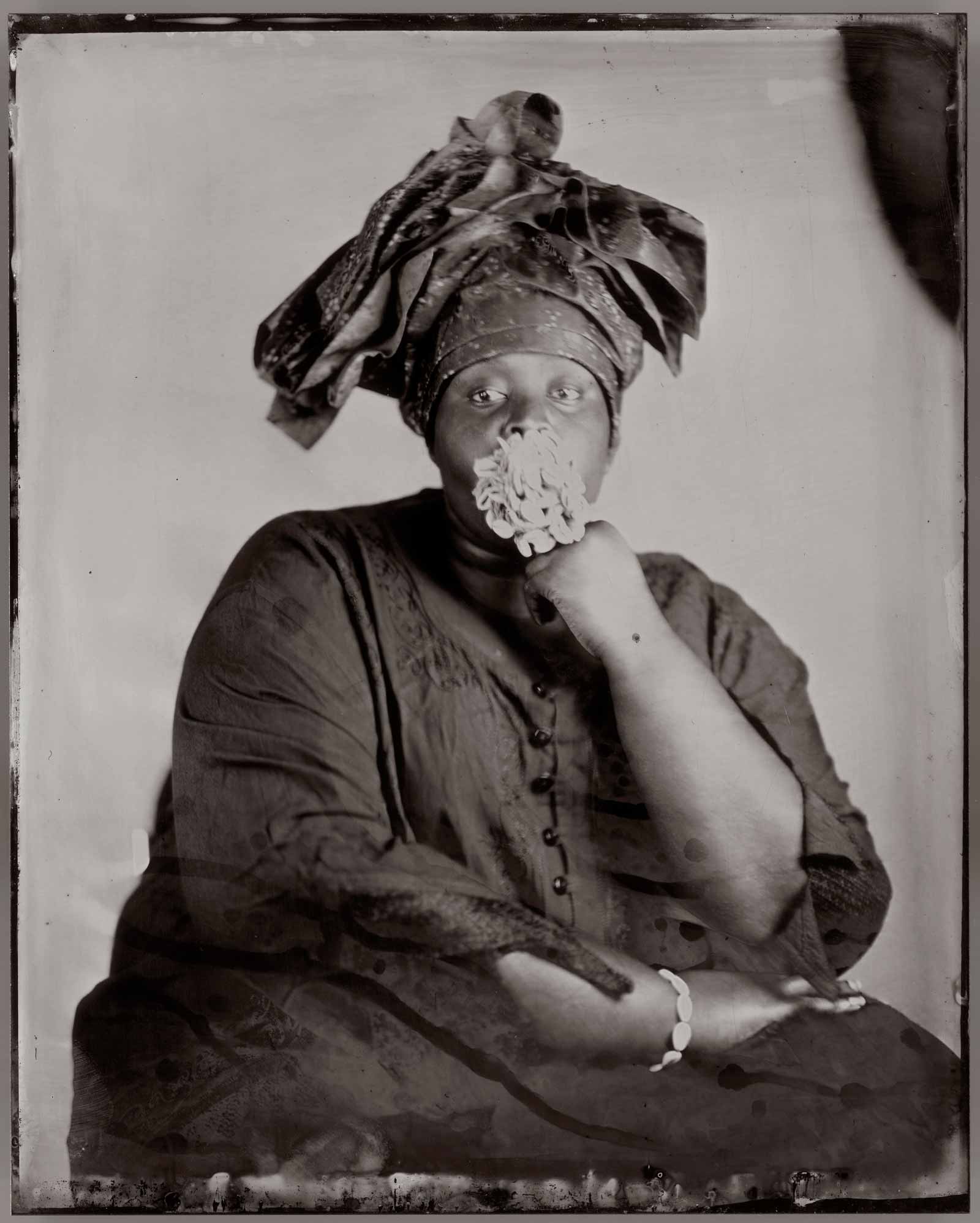

Meanwhile, back in the new gallery, where most of “Actions” is displayed, it’s another example of past-meets-present that caught my attention: Khadija Saye’s striking wet plate collodion tintypes, a method of early photography. Limon, Peitaw, Teere, and Nak Bejjen, four stunning photographs from Saye’s series Dwelling: in this space we breathe—each of which depicts a different traditional Gambian spiritual ritual—are eerily reminiscent of the spirit photos so popular at the end of the nineteenth century, light pooling like liquid or shimmering like smoke around the female subject in each frame. They’re ghostly in more ways than one, as they were taken shortly before twenty-four-year-old Saye—an artist at the very beginning of what looked set to be a brilliant career—died in London’s Grenfell Tower fire last summer.

Admiring the many Gaudier-Brzeska sculptures displayed around the house, I was struck by the parallel between the French-born, London-based sculptor—killed in action in 1915 at the tender age of twenty-three—and Saye’s untimely fate. In 1927, Ede purchased close to the entire estate of Gaudier-Brzeska—sealing Ede’s reputation as a collector in the process. Thereafter, Ede dedicated himself to winning for the French sculptor the recognition Ede felt his talent deserved, an act of memorialization implicit in Nairne’s inclusion of Saye’s work.

It is widely acknowledged that Ede’s own traumatic experiences of fighting in the trenches of World War I irrevocably shaped his vision for Kettle’s Yard as a sanctuary for both people and art. To spend a few hours there is to realize just how much such a space is still needed today.

Kettle’s Yard is open Tuesday through Sunday. “Actions. The image of the world can be different” is on view through May 6.