In June 2014, after three Israeli teenagers went missing from a settlement, Israel launched Operation Brother’s Keeper, one of the most sweeping manhunts in the nation’s nearly seventy-year history. The dragnet, in which Israel arrested hundreds of Palestinians in the West Bank without charge, ended eighteen days later when soldiers discovered the murdered Israeli teenagers’ bodies under a heap of rocks. In keeping with Jewish tradition, the families buried their sons the next day. As the nation mourned, three Israelis seeking revenge abducted a sixteen-year-old Palestinian, Muhammad Abu Khdeir, while he was walking to his local mosque in Jerusalem after a pre-dawn meal during the holy month of Ramadan. He was bludgeoned and then burned alive. A fifty-day armed conflict between Israel and Hamas ensued, in which Israel bombarded the overcrowded Gaza Strip with airstrikes that exacted a high civilian death toll, killing over 500 children.

The climate in Israel was tense and bellicose. As Hamas fighters fired rockets from Gaza at central Tel Aviv, right-wing Israeli nationalists assaulted antiwar protesters while chanting “Death to Arabs!” and “Death to leftists!” Veteran artists and public figures were labeled as traitors and received threats for even expressing regret at the loss of Palestinian children’s lives. One of Israel’s best-known poets, Natan Zach, now eighty-seven, told the Israeli website Walla! at the time: “The reason I no longer write in the papers is that I’m afraid someone will grab me on the street and beat me.” A month after a cease-fire was agreed, Israel’s then foreign minister, Avigdor Lieberman, decided it was time for his ministry to cut off all future support for the Israeli dancer and choreographer Arkadi Zaides for a work that allegedly vilified Israel’s military.

Zaides’s Archive is a solo dance piece set against a backdrop of video footage of Israeli soldiers and settlers in the West Bank. The footage was provided by B’Tselem, an Israeli group that documents human rights abuses in the Occupied Territories and has become anathema to the Israeli political establishment. Last year, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu canceled a meeting with the German foreign minister, Sigmar Gabriel, after Gabriel met with representatives of B’Tselem and Breaking the Silence, an anti-occupation organization of former Israeli soldiers who publish testimonies about their service in the West Bank and Gaza. (Israel’s cabinet is currently promoting one bill that would ban members of Breaking the Silence from speaking in high schools, and another that would effectively outlaw them.)

“The moment I was linked to B’Tselem, that was it,” said Zaides, who was born in Belarus and moved to Israel at the age of eleven. “It’s black and white. They said, ‘He is damaging to soldiers and that’s it.’ None of them had seen the work.” In Archive, Zaides appears on stage in front of a giant screen, looking on with the audience as he projects excerpts from years of material captured by Palestinian civilians armed with cameras. In one scene, a soldier cocks his gun and retreats; in another a settler, his shirt tied around his face, throws stones. Zaides then simulates their movements, gestures and sounds in perfect synchronization. “I look at bodies of Israelis and put them in my own body. By this action, I question what is happening to our collective body,” he told us from Belgium, where he is now part-based, dividing his time between there and France.

Before the Foreign Ministry pulled its funding, the piece had already encountered local resistance. In 2014, after pressure from a few right-wing activists, as well as from a group called Mothers of Soldiers Against B’Tselem, the municipality of Petah Tikva, a working-class city just outside Tel Aviv, called on its local museum to shut down a video installation of Archive. The museum stood its ground, but when Zaides began performing the show in small theaters around Israel, protests were organized. One, in Jerusalem, became violent: audience members were verbally abused and physically assaulted outside, while Zaides himself needed a police escort. When, in 2015, Zaides was due to perform Archive in Paris, Israel’s justice minister, Ayelet Shaked, asked the French ambassador to Israel to shut it down on the grounds that it showed “terrorists as victims and IDF [Israel Defense Forces] fighters defending Israeli citizens with their bodies as criminals.” Later that year, Miri Regev, a newly appointed minister of culture and sport from Netanyahu’s Likud Party who had lambasted Zaides’s show before assuming her post, removed the ministry’s logo from the list of sponsors and promised to review its support.

Advertisement

Zaides went on to raise outside funds and perform Archive abroad without the foreign ministry’s money. “My work has become more radical because things have gotten more radical,” he added. “It’s not just politicians; it’s a social phenomenon. A lot of these voices are coming from the bottom up, and the politicians are reacting.”

Netanyahu, who is now Israel’s second-longest-serving prime minister, oversees the country’s most overtly right-wing government in history—one dominated by settlers and nationalists who reject a two-state solution, deny that an occupation exists, and openly seek to bolster Jewish power at the expense of democratic practices. In recent years, Israel’s parliament has passed a series of combative, censorial laws, including legislation limiting the funding of human rights organizations and, most more recently, a law barring entry to foreign nationals who actively call for boycotting Israel. In early 2018, Israel published a blacklist of twenty organizations whose leaders it has barred from entering the country because of their advocacy for the boycott, divestment, and sanctions movement.

It is hard to reconcile this political landscape with the breezy, mostly hedonistic atmosphere in the gay-friendly coastal city of Tel Aviv. Often referred to as “the bubble,” Tel Aviv has always been the country’s de facto cultural hub. A clutch of makeshift artist studios and contemporary art galleries, many of which participate in the prestigious Art Basel and Frieze fairs, operate there alongside a number of cinemas playing independent films. Art and the nation have always been inextricably linked; the national theater, Habima, was formed before the state was founded, and the ceremony proclaiming the establishment of the State of Israel took place on May 14, 1948, at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art. But the tacit acceptance of pockets of dissent—once touted as proof of Israel’s vibrant democracy and diversity—is vanishing even from this liberal redoubt.

“I’m used to a life in which there is some invisible wall separating my personal, everyday life from my life as a writer and as a public figure,” said Etgar Keret, one of Israel’s most internationally acclaimed authors, when we met him in a quiet, sun-drenched café in North Tel Aviv. “In the last Gaza War, I felt this wall collapse, and suddenly there was no separation between my two identities. To some, I wasn’t just someone thinking differently but a traitor who had exposed his true face and was trying to destroy his own society and country.”

Keret is married to the actress and filmmaker Shira Geffen, with whom he won the Cannes Film Festival’s Caméra d’Or award in 2007 for their movie Jellyfish. During the 2014 war, Geffen asked the audience at a screening of one of her films at the Jerusalem Film Festival to stand for a minute of silence to mark the killing of four Palestinian children by an Israeli missile on the beach in Gaza that day. Facebook groups and comments soon sprang up that included debates about the best way to attack her. A barrage of personal threats ensued. “The message for artists is that nothing good can come from being outspokenly politically left-wing,” said Keret, “but in many cases, something bad can come out of it.”

The Israeli actress Einat Weizman, an unassuming woman with jet-black hair and fair skin, is a local celebrity for her roles in romcoms and a popular 1990s TV show. Today, Weizman says she can no longer work in Israeli theaters. During the summer of 2014, she describes becoming a target of vicious harassment and incitement after a Facebook user posted a 2006 photo of her wearing a T-shirt that read “Free Palestine.” The timing and the language of the post made it seem as if the photo had been taken during the war. “I was Facebook-lynched,” she says. “I got thousands of hate messages, from people who wanted to kill me and rape me. And because they knew me in Israel as an actress for twenty years, it moved from Facebook to the streets.”

Weizman told us that people in her neighborhood had shouted and spat at her, forcing her to ask friends to escort her. “I had to process this experience somehow because my mental state was not good,” she said. The turmoil led to the play Shame, which she wrote and directed in 2015. Since then, she has decided to produce explicitly political work focused on Palestinian stories. “I think the situation in Israel is so dramatic and apartheid especially is so bad that I need to take a clear stand,” she told us, “and I’m doing theater just for this reason.” Last year, a play she wrote called Prisoners of the Occupation was rejected by an annual fringe theater festival in the northern Israeli city of Acre. The play, based on Weizman’s research into the history of Palestinian hunger strikes in Israeli prisons, tells the story of Palestinian prisoners through their letters. “Every fourth Palestinian man was, will be, or is serving a prison sentence,” she said. “For Israelis, the occupation is fences and walls and checkpoints, but for Palestinian society the occupation results in prison.”

Advertisement

In an unprecedented move, the festival’s steering committee, which includes Mayor Shimon Lankri, a Likud member, voted to exclude the play from the program, claiming it could provoke tensions in the mixed Arab-Jewish city. Fellow artists who were to participate in the festival, members of the artistic committee, and, ultimately, the artistic director all resigned from the festival in protest. But Culture Minister Regev applauded the decision, saying, “The Palestinian narrative will not be funded by the Israeli government or public funds,” and suggested Weizman “go to Ramallah” and put on her show there.

Regev, who previously served as IDF spokesperson and chief military censor, is a rising star in the governing Likud Party, and some believe she is ambitious to succeed Netanyahu. Notorious for her incendiary, populist rhetoric, she once called African asylum seekers “a cancer in our body.” In January, she posted a video to Facebook of herself with members of Beitar—a soccer club known for its anti-Arab racism—as fans chanted in the background at the rival Arab team, “May your village burn down.” (The video has recently been removed.)

Like many in the ruling coalition, Regev is openly against the establishment of a Palestinian state and has proposed annexing parts of the West Bank. But unlike a majority of her cabinet colleagues, who are from more privileged Ashkenazi backgrounds (that is, Jews of European descent), she is a Mizrahi woman of Moroccan descent from a housing project in the working-class town of Kiryat Gat. (Mizrahim, or “easterners,” are Jews from countries in the Middle East and North Africa, some of whom trace their origins back to Spain and Portugal.) She curries favor well with voters, many of them Mizrahim like herself, in part because she fuses her political agenda with her promise to upend the monopoly that the Ashkenazi elite, historically more identified with the peace camp in Israel, has had on the country’s cultural establishment. “I have never read Chekhov,” Regev has declared, flaunting the fact that her cultural reference points are not those enshrined in the Israeli canon, which has marginalized the history and culture of non-European Jews. (In 2016, the Education Ministry formed a committee to integrate more Mizrahi heritage into Israel’s history textbooks.)

Osnat Trabelsi, a Mizrahi producer and filmmaker who has made groundbreaking documentaries that focus on Palestinian life under occupation—like Arna’s Children, about a theater for kids in the West Bank city of Jenin run by a Jewish woman—is on the opposite end of the political spectrum from Regev. Even so, Trabelsi believes that, as problematic a figure as Regev is, Ashkenazi men in positions of power have often treated her in patronizing and racist ways. “I don’t agree with her on many things,” she said, “but I cannot ignore the fact that she raises issues you could not talk about before.” Trabelsi says that in her thirty-year career the decision-makers she has met on the film and television boards have all been Ashkenazi men. For her, Regev’s ascent has exposed both Ashkenazi-Mizrahi and male-female disparities in Israel’s culture industry—if only on the level of rhetoric. “She hasn’t really made a change,” said Trabelsi. “Where are the film funds in the north or south of the country?” The more significant effects of Regev’s tenure, Trabelsi thinks, have been due to her hard-line rightist politics, since fewer and fewer political documentary films are being made—“there is fear, there is self-censorship.”

In her position as the country’s leading cultural watchdog, Regev has taken every opportunity to cut funds, or threaten to do so, to artists or institutions she deems harmful or offensive to the state. One of her first acts as culture minister was to levy financial penalties on theaters, dance troupes, or orchestras that do not perform in the settlements—and provide bonus payments to those that do. She has also said that she wanted to pull funding from several established national arts festivals because of performances involving nudity and from fringe theaters presenting subversive content. Although successive attorney generals have told her that her interference infringes on freedom of expression, that has not stopped her from crusading on the motto “freedom of expression, not freedom of funding.”

Since 2015, Regev has been a party to measures that effectively closed down the Al-Midan repertory theater, which self-identifies as the only Palestinian-Arabic theatre within the 1948 borders. Established in 1994, the small Haifa-based theater runs on an annual budget of about $1 million (of which 65 percent comes from the government, the rest from ticket sales). Much of the theater’s public funding has been withheld since 2015 when the company staged “A Parallel Time,” a play about six political prisoners in an Israeli prison, of whom one, a musician, has been granted permission to marry. The other prisoners try to make him an oud as a wedding gift, and we watch as they struggle to contrive the parts for it. The playwright, Bashar Murkus, created the piece from materials and letters from the prisoners—among them, Walid Daka, a Palestinian serving a life sentence for the kidnapping and murder of an Israeli soldier, Moshe Tamam, in 1984.

The play was performed dozens of times in Arabic, but it was when Hebrew subtitles were added that opposition arose. At first, pressure came from right-wing activists and the Tamam family, who protested outside the theater and called on the city to shut down the play, claiming that it supported terrorism. Then a barrage of attacks from the government followed. The Haifa municipality, which provides 40 percent of the theater’s budget, froze Al-Midan’s funds. A month later, Regev followed suit, cutting her ministry’s 25 percent contribution. The education minister, Naftali Bennett, rescinded the play’s eligibility for subsidized performances in schools. After Al-Midan sued the city, a court eventually determined there was no legal basis for withholding funding, and it was eventually reinstated.

During that time, according to the theater, a terrorism victims’ association supporting the Tamam family filed some forty-five complaints with Israel’s NGO registrar, alleging mishandling of funds by the theater. Not a single one of these claims was validated, but the comprehensive audit to investigate meant that funding for the theater was frozen for eighteen months. Even after Al-Midan cleared those bureaucratic hurdles, at the end of 2016, and began to receive its municipal funding again, the Culture Ministry still held out. “Miri Regev works for us; we pay her salary,” said Amer Hlehel, an actor and former artistic director of Al-Midan, who met with us in a café on Haifa’s main boulevard. “We are the people, the citizens, the taxpayers, and she is there to serve us.”

Despite a legal obligation to restore funding, Regev has yet to comply. “Occupation is not always a land grab; it’s also collecting your taxes but not paying your budgets,” remarked Al-Midan’s board chairman, Jozef Atrash. The Culture Ministry’s latest argument is that Al-Midan has lost its funding because it failed to fulfill its quota of performances. “If you’re a theater and you’re not working like a theater,” said Galit Wahba Shasho, the director of the Culture Ministry, who runs day-to-day operations for Regev, “you won’t be granted government money.” This appears to contradict an agreement reached in 2016 that the theater’s reduced operations during the budget freeze would not affect its eligibility for funding. Al-Midan has petitioned Israel’s Supreme Court to resolve the issue.

We met with Wahba Shasho in her spartan Tel Aviv office after learning that Minister Regev herself would not be available for the interview we’d requested. A woman sat in the corner silently monitoring our conversation, and Wahba Shasho kept a ministry press officer named Heli Samama-Fadida on speakerphone from Jerusalem while we were there. In answer to our questions about the ministry’s problems with Al-Midan and with Einat Weizman’s work, Wahba Shasho repeated that artists can do what they want but if they want state support, they must abide by “the letter of the law.” She repeated the phrase nineteen times during our interview. “Regev wants to legislate a more authoritative law that would draw a distinction between freedom of speech, which we all believe in and all hold up to,” said Wahba Shasho. “But if you want to get government money, you cannot go against the existence of the State of Israel.” When the interview concluded, both Samama-Fadida and Wahba Shasho demanded that we supply a copy of our recording.

Regev boasts of raising budgets for marginalized groups outside the center of Israel, including Palestinian citizens, who comprise over 20 percent of the country’s population. “Regev has tripled the budget to Arab culture,” Wahba Shasho said, “because she is motivated by cultural justice and equality.” Regev has indeed raised the ministry’s total annual budget from 650 million shekels to nearly 1 billion. But according to Jafar Farah, head of the Mossawa Center, an organization that promotes civil and equal rights for Israel’s Palestinian citizens, Regev increased the budget for Arab culture from 11 million to 34 million shekels only under the compulsion of a high court order in 2015, resulting from a 2012 petition by Mossawa. Even after the increase, Farah says, the Arab share of arts funding is still just 3 percent of the Ministry’s budget.

For Farah, talk about expanded budgets overlooks the lack of basic infrastructure for Palestinian artists. “The money is meaningless since there is no Arab museum, no school for Arab theater, no Arab fund for cinema. The way the system works, a Palestinian filmmaker cannot dream in his own language,” he said, noting the absence of Palestinians on any of the film committees that allocate funds. “If you have a dream in Arabic, you need to translate it into Hebrew—and this already damages it. The majority of great Palestinian filmmakers left because they couldn’t get the funds.”

Some draw parallels between the cultural climate here and that in the United States in the late 1980s, when conservative politicians used transgressive or provocative work by the photographer-artists Robert Mapplethorpe and Andres Serrano as an excuse to call for ending federal funding of the arts in general. The self-appointed crusader in this cause, Senator Jesse Helms, singled out Serrano, in particular, as a “jerk” who was told not to “dishonor our Lord” for his image of a crucifix submerged in urine, Piss Christ.

“The crux of contemporary censorship is the funding aspect,” said Chen Tamir, the curator of Tel Aviv’s Center for Contemporary Art. “Just as in the American culture wars, public funding here is being manipulated to become a mechanism of censorship.” Following Helms, Regev has proposed a law—dubbed the Loyalty in Culture Bill—that would give the culture minister the authority to deny funding to arts institutions on broad grounds that involve voicing criticism of the state of Israel. (Similar powers already belong to the Finance Ministry; Regev seeks to arrogate them for herself.) Introducing the bill on the floor of the Knesset in January 2016, Regev declared:

I will not be an ATM. I have a responsibility for public monies, and this law would grant me the authority to exercise my responsibilities and to deny support for institutionalized violations of the law.

Regev’s bill awaits final passage, but she has not hesitated to use the levers of power already at her disposal to influence institutions that were once accustomed to creative independence. Unlike the US, Israel has no real culture of philanthropy. Taxes are high and people expect the government to provide for them—a vestige of the country’s socialist origin story—including culture and the arts. “There are only a handful of good contemporary art institutions, commercial galleries, and funders or other partners that can facilitate the creation of artwork,” said Tamir. “So if you’re an artist whose work might jeopardize an institution, you’ll really have to struggle to find ways of funding and showing your work.”

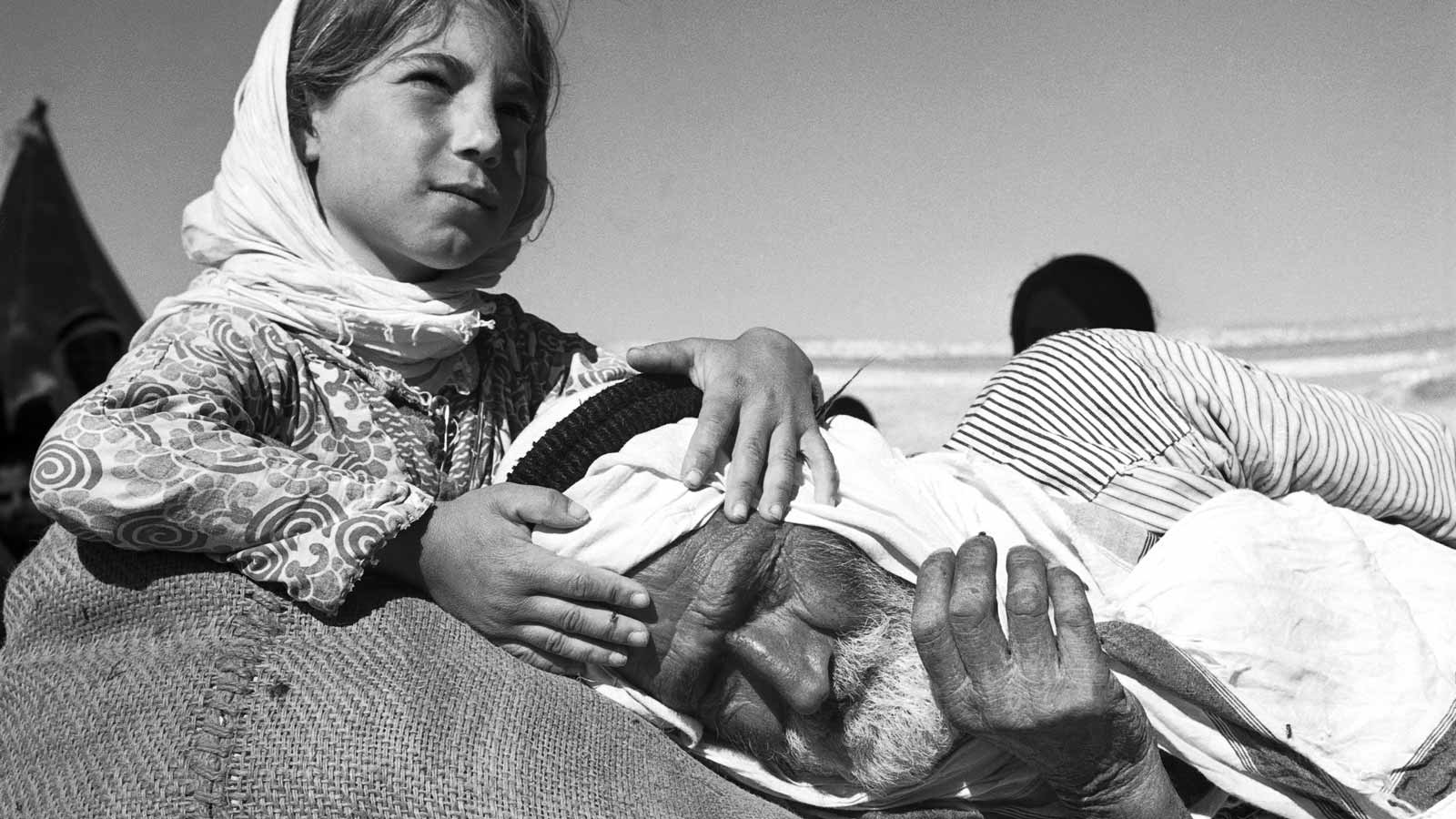

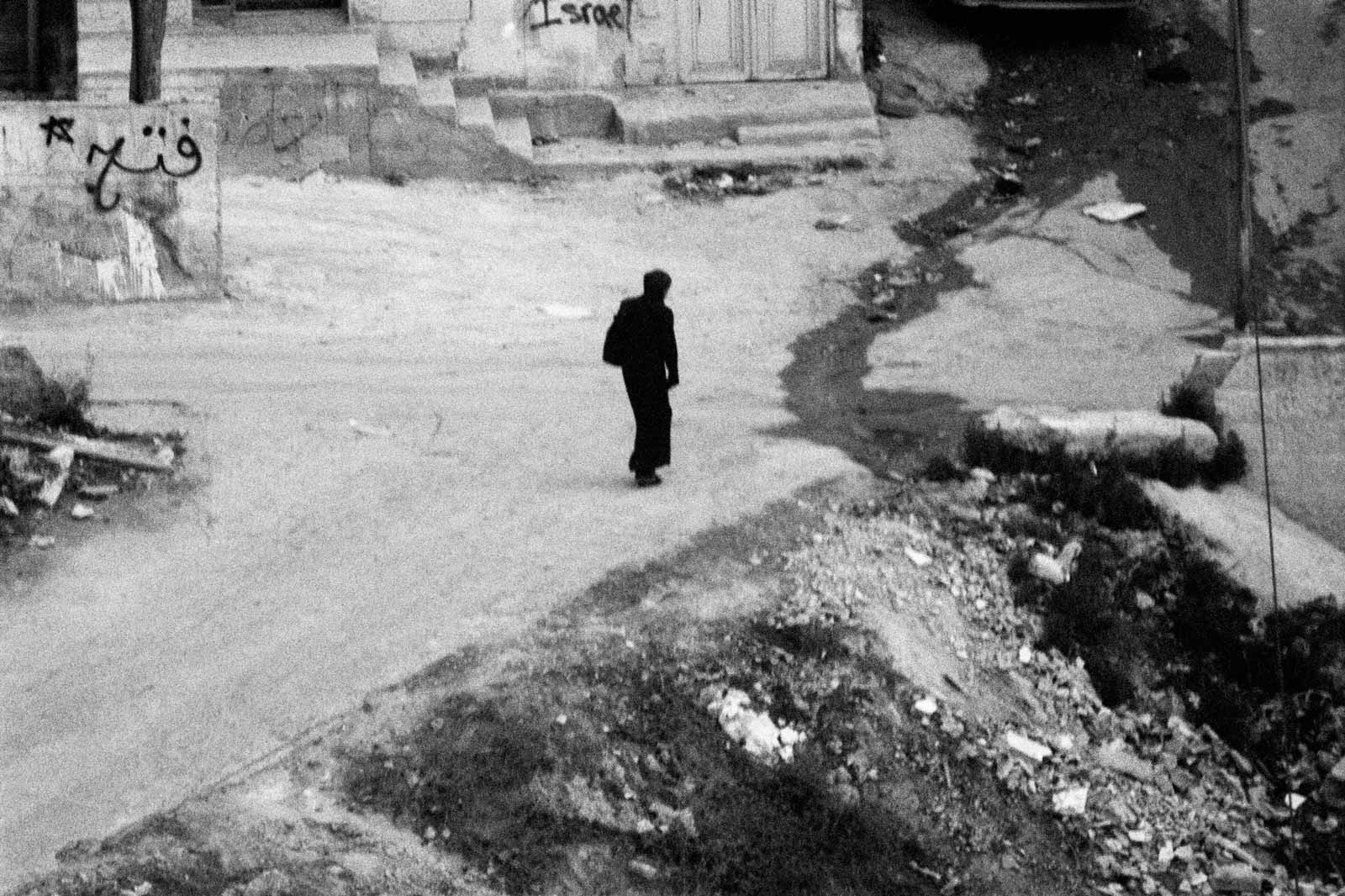

The ubiquity of state funding—and most institutions’ dependency on it—mean that it is virtually impossible to create work in Israel without coming into contact with the government. Natasha Dudinski is the artistic director of “48mm Film Festival,” an annual event that curates and screens movies locally about the Nakba (“catastrophe” in Arabic), the word Palestinians use to describe the consequences of the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, primarily the forcible displacement of 700,000 Palestinians. The social justice organization Zochrot (“remembering” in Hebrew), which founded the festival in 2013, has faced police harassment over its work to raise awareness about the destruction of Palestinian villages during Israel’s War of Independence. To maintain its artistic and political independence, “48mm” has never sought or accepted money from the Israeli government. Although the festival has always been a punching bag for right-wing politicians, Dudinski fears that even the festival’s financial independence may not be enough to protect it from Regev’s efforts at censorship.

In November, just two weeks before the festival was to begin, Regev asked Finance Minister Moshe Kahlon whether the Tel Aviv Cinemateque could be fined for holding screenings as part of “48mm,” asserting that the use of a screening room was an in-kind donation that violated the existing law that prohibits marking Israel’s Independence Day as the Nakba. Although Kahlon demurred on this point, other screening partners of the festival, such as the Arabic-Hebrew Theatre in Jaffa (also known as Al-Saraya), which caters particularly to the country’s Palestinian population, withdrew their participation for fear of government retribution. “It was really hard for me to see Al-Saraya giving up because of fear,” Dudinski said. “And it’s not only them—the situation is weakening everybody and giving the government more power because they see what they can do.”

The photographer Miki Kratsman has covered the Israeli-Palestinian conflict for more than three decades. His body of work includes the 2010 project Targeted Killing, in which he used a long-range camera lens to mimic photographs taken by a drone of unsuspecting Palestinians, and a more recent series, developed with a grant from Harvard University, which consists of thousands of portraits of Palestinians in the Occupied Territories. That project was slated to appear alongside a show on refugee camps by the Chinese dissident artist Ai Weiwei at the prestigious Tel Aviv Museum of Art, but the show never took place. After pushing the opening back several times, the museum cited a scheduling conflict, but most Israeli artists considered it a case of self-censorship. “We can teach about Guernica, but we can’t produce our own Guernica,” Kratsman said over lunch near his studio. For Kratsman, the move foreshadows a more serious shift in Israeli society. In the coming years, he said, “it’s going to be about what you are allowed to say and not allowed to say; where you can be and can’t be; with whom you will be able to talk. We are just at the beginning of it.”

For many Palestinian citizens, like the poet Dareen Tatour, that time already arrived. In the early hours of October 11, 2015, a large police force descended upon her parents’ home in a suburban hillside town outside Nazareth and hauled Tatour off to the local police station. Before her arrest, Tatour worked as an office manager at a marketing firm. She had felt compelled at the time to write a Facebook post about the violent deaths of several Palestinians at the hands of Israelis. Her text included the phrase, “I am the next shahid.” In Palestinian culture, the word shahid (martyr) means, first and foremost, a victim. But for Israelis, it is code for suicide bomber. She had also posted a poem on Facebook that included the line “Qawem ya shaabi, qawemhum” (“Resist, my people, resist them”), alongside a video showing Palestinians throwing rocks and burning tires. Tatour says her words were an ode to all Palestinians, but for Israelis tasked with surveilling social media for clues to potential attacks, her words amounted to incitement to terrorism. (Tatour denies that she either incites or supports terrorism.)

At the time of her arrest, Tatour had no idea what it was about. The questions police put to her did not point to any crime. Instead, she was quizzed about her politics, her religion, her writing, and who her friends were. For three weeks, she says, she was cut off from her parents, forced to wear the same clothes she arrived in, and denied every request for pen, paper, books, and TV access. Only during the fourth round of interrogation did she finally understand the grounds of suspicion: “One poem. One photo. One Facebook status,” Tatour says with both indignance and humor.

After nearly a hundred days of detention, Tatour was indicted on November 2, 2015, for incitement to violence and terrorism, and support for a terrorist organization. She has been under house arrest for two and a half years now, initially obliged to wear electronic cuffs around her ankles, and forbidden from using the Internet or even a computer. We met with Tatour two weeks before her case’s closing remarks. She greeted us with a grin from the edge of her parents’ driveway, the farthest point she can travel outdoors alone, wearing a white hijab.

“Until now, I have been asking myself in many of the poems I wrote in prison, Why is poetry being accused?” Tatour said. “They want to paint a picture without occupation. But I live through it. I can’t write what they want. They want me to write that there is no occupation, no Palestinian people. It’s impossible. I am living it.” Tatour has been charged and now awaits the verdict, but says that whether she goes back to jail or not, she has her next book ready to go to press, and is finishing a memoir about her experience in prison. “If we are silent, we get ourselves in a worse situation. We cannot give them what they want.”

While few in Israel have heard of Tatour, Israel’s war on culture has recently found a much more high-profile target. On March 13, Israel’s ambassador to France, Aliza Bin-Noun, boycotted the opening night of the Israeli Film Festival in Paris because the program was headlined by Foxtrot, a feature film about the trauma two parents suffer after losing their son during his military service. The film—directed by acclaimed Israeli filmmaker Samuel Maoz, an IDF veteran of the 1982 Lebanon war—has won the Grand Jury Prize at the Venice Film Festival, swept the Ophir Awards (Israel’s equivalent of the Oscars), and was shortlisted by the Academy Awards (though it fell short of a best foreign film nomination). The story includes a scene in which Israeli soldiers cover up the murder of Palestinians. Although, by her own admission, Regev has not seen the film, she said it “harms the good name of the IDF” and that its selection for leading film festivals is “a disgrace.” And she used the occasion to repeat her threats about funding: “Whoever wants to make a movie like this can do so with their own private money.”

Israel’s Foreign Ministry has supported the Parisian festival since it launched eighteen years ago, and claims never to interfere with artistic content. But this year, the Ministry—headed by Netanyahu, who has subsumed the foreign minister’s portfolio’s into his own—asked the festival organizers to select a less “controversial” film “more suitable for the festive opening evening, which will include an audience of Jewish donors.” When the organizers refused, the Foreign Ministry instructed its ambassador to boycott the event—although the ministry spokesperson, Emmanuel Nahshon, rejected this characterization, insisting, “It is not a boycott; it is an act of protest.” Several weeks after the decision to boycott opening night was made public, the Foreign Ministry apparently softened its opposition by sending a cultural attaché to attend.

When Foxtrot won best film at the recent Ophir Awards, the actor Lamis Ammar, a Palestinian citizen of Israel who starred in the acclaimed Sand Storm (2016), was presenting the best supporting actress award. On stage, she told the audience of her mixed feelings about participating. “The industry has demanded that I conceal my Palestinian identity and political opinions for the sake of the assumed and unassumed racism of the viewers,” she said, going on to relate how she had withdrawn submission of a play she wrote for the Acre festival, out of solidarity with a “censored Israeli artist”—referring to Einat Weizman. “We will not stop creating. We will create with or without funding. From this stage, and if necessary, from prison, like Dareen Tatour.”

It is no accident, she said, that she has been unable to find funding in Israel for her play because “most Israeli art, at the end of the day, serves to justify Israeli wrongdoing, instead of addressing and eliminating it.” Ammar believes there are only a handful of Israeli artists, such as Einat Weizman, who consistently challenge the system. “Everyone is talking about silencing these days because Regev has begun silencing Jews, and it is new for them,” she said, “but we [Palestinians] have been silenced since 1948.”

Another dissident Israeli artist is Udi Aloni, a filmmaker who splits his time between Tel Aviv, Berlin, and Brooklyn. Aloni is the son of Shulamit Aloni, a revered former culture minister and a pioneer of the nation’s civil rights movement. Before his mother’s death, in 2014, he was regarded as untouchable, and the films he made—many of them focusing on the destructive realities of the occupation—were funded by the government. His last, the award-winning Junction 48 (2016), centered on the aspirations of a Palestinian rapper living in Lod, a mixed Arab-Jewish city with high crime rates, and where there have been Israeli demolitions of Palestinian homes. Today, though, in the Regev era, Aloni believes it’s unlikely that he’ll receive state funding again for work that highlights the plight of Palestinians.

“I can’t stop the flood, but I can create Noah’s ark,” he said. “And when the flood destroys all, we will be there to fill the void.”

While Regev has not been able to make good on many of her threats, the rhetoric has created a sufficiently fraught atmosphere that much of her strategy is in effect. She has managed to revamp what was once a small, overlooked ministry into a powerful mouthpiece for the Netanyahu government, putting Israel’s cultural elite on the defensive and setting a precedent for her successors. Regev, who has set her sights on becoming minister of defense in the next government (this would make her the first woman in this role), is just one manifestation of the rightward, nationalist, pro-settler drift of Israeli politics. Although Netanyahu is currently mired in several corruption investigations, and there has been talk of possible early elections, polls show that his Likud Party would nevertheless likely win a plurality of seats in the Knesset—making it easy to imagine his re-election. With no political alternative from the center and left to speak of in Israel right now, any resistance against the Likud agenda from Israel’s small community of artists and intellectuals seems like a voice in the wilderness. And Regev has capitalized on this moment masterfully. While her tenure may not represent a permanent, more coercive and censorious change in how the arts are funded in Israel, she embodies the sea-change in Israeli society, from a country that downplayed its inequities and declining democratic norms, to one that flaunts them.

Research for this essay was supported by the Artis Grant Program.