“Inventur,” the title of the exhibition of German art from 1943 to 1955 currently on display at the Busch-Reisinger Museum at Harvard University, means stocktaking. It refers, according to the curator Lynette Roth, to “the act of physical and moral stocktaking by German artists in the aftermath of war as reflected in the stuff of everyday life.” The name for this sumptuous and wide-ranging collection of works has been carefully chosen to accommodate the diversity of approaches and materials on display, and to sidestep the temptation to explicate German art from this period in light either of pre-war German work or of cold war politics.

The Busch-Reisinger Museum (formerly the Germanic Museum; now incorporated into the Harvard Art Museums) is uniquely placed as the organizer of this important show. Charles Kuhn, the museum’s curator from 1930 to 1968, collected works by many of the artists on view, starting with the acquisition of Fritz Winter’s In Front of Red in 1951, “the first work… [they purchased] by an artist who remained in Nazi Germany during the war.”

Younger generations may not fully appreciate the degree of resistance to Germany in this country (and elsewhere) that persisted for much of the second half of the twentieth century. As Ilka Voermann points out in her essay in the accompanying catalogue, “An Absolutely Unknown Aspect of Modern Art,” the war, Nazi crimes, and their legacy inevitably prejudiced Americans against German art and prompted curators and museum directors to reject proposals for exhibitions. In 1950, the director of the Art Institute of Chicago suggested that were his museum to show an exhibition of contemporary German work, it “would run against great objections.”

The works so handsomely shown at the Harvard Art Museums represent, then, a retroactive restitution of what has been missing from the American narrative of twentieth-century German art. The exhibition is in interesting conversation with several smaller shows currently at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts: “Beckmann in America,” which explores the influence of German émigrés Max Beckmann and Karl Zerbe on the Boston Expressionists, along with “The German Woodcut: 70s into 80s” and “The German Woodcut: Christiane Baumgartner.” Viewers can trace the relation of post-war artistic works in Germany both to what came before and to what came after. Beckmann, for example, was condemned by the Nazis as a degenerate artist and fled Germany for Amsterdam, while the later woodcuts have antecedents, both of medium and content, in the Harvard show. “Inventur” fills a lacuna in our understanding, enabling us to make sense of the sweep of German art in the twentieth century—and it does so with considerable care, taste, and élan.

Many of the artists here will be relatively new to American audiences, which are likely more familiar with pre-war German names—Beckmann, Dix, Grosz, Klee, Kandinsky—and contemporary ones—Baselitz, Richter, Kiefer. The exhibition features late works by Otto Dix, as well as by Fritz Winter (including that first acquisition), and an exhilarating range by Willi Baumeister, with exuberant large paintings such as Growth of the Crystals II (1947–1952) and Large Montaru (1953). The energy, colors, and lines of these later Baumeister works, recalling Kandinsky and Klee, delight—but more unexpected are the small early lacquers he produced, along with Oskar Schlemmer and Franz Krause, in Wuppertal in 1941. Their ethereal beauty in the face of such destruction is itself a type of resistance.

There are, necessarily, works that directly depict or respond more obliquely to the horrors of war: Wilhelm Rudolph’s powerful drawings of Dresden after the bombing; or Erwin Spuler’s Bombed-Out Buildings (1946–1948), a rendition of havoc that, in its uniform repetitions of the buildings’ destruction, approaches dark abstraction; or Karl Hofer’s Night of Ruins (1947), in which buildings themselves have become gaping, almost hysterical, masks. Richard Peter’s photographs capture human resilience amid the rubble, whether at an outdoor mass (Sunday Service, Schäferstr., 1946) or in the form of a young woman in a cheery hat reading against a ruin (Reading Woman Sitting on the Protruding Wall of a Ruin (Johannstrasse Tram Stop), 1946). Perhaps most haunting are Gerhard Altenbourg’s drawings, such as Ecce Homo Dying Warrior (1949), in which the central figure appears almost a torn spider’s web of a man, his carcass inhabited by spindly ghosts. Altenbourg’s drawings enact the trauma that produced them: their devastation is not primarily structural, like that of the actual ruins featured in so many works; rather, it is a devastation of the soul.

Advertisement

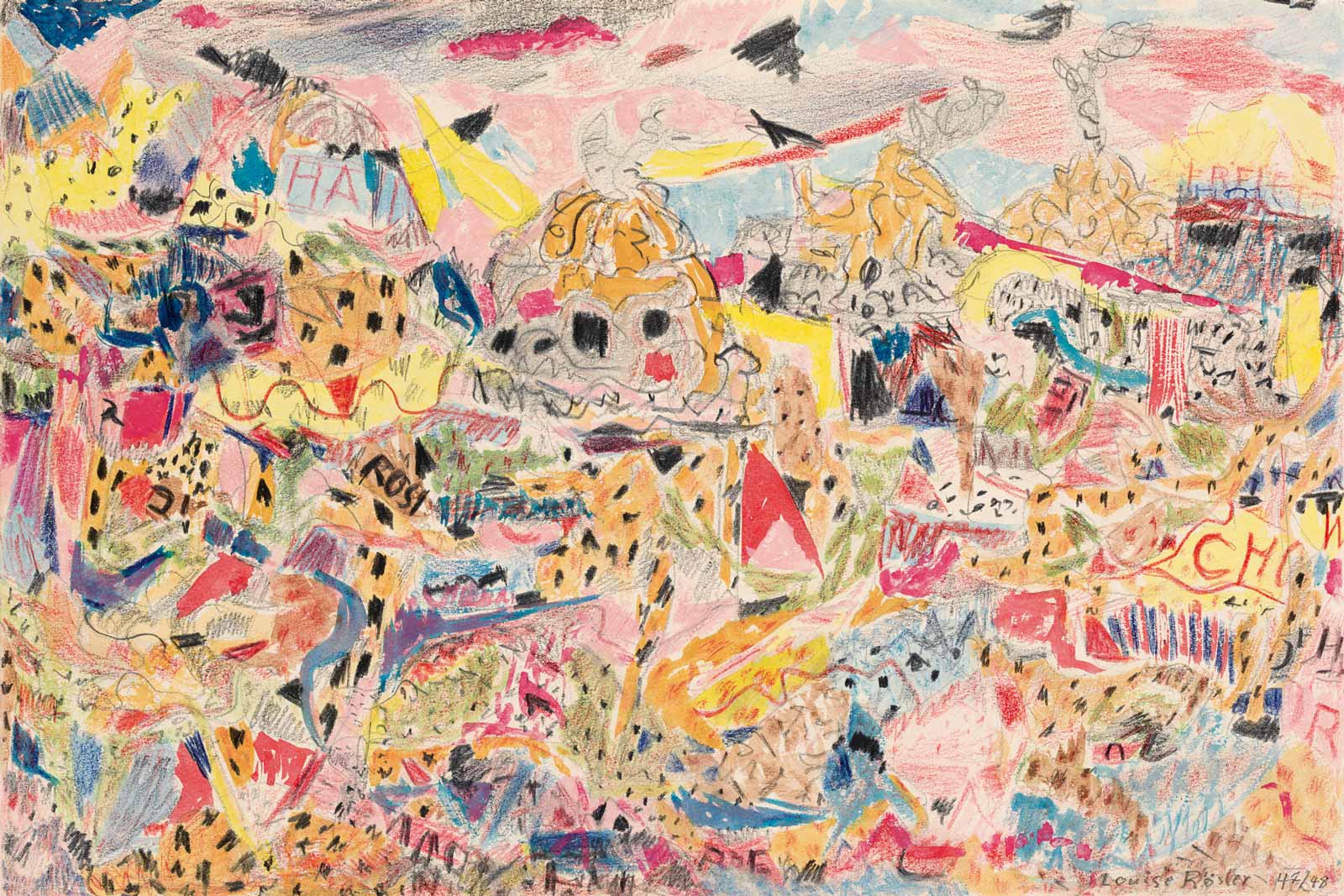

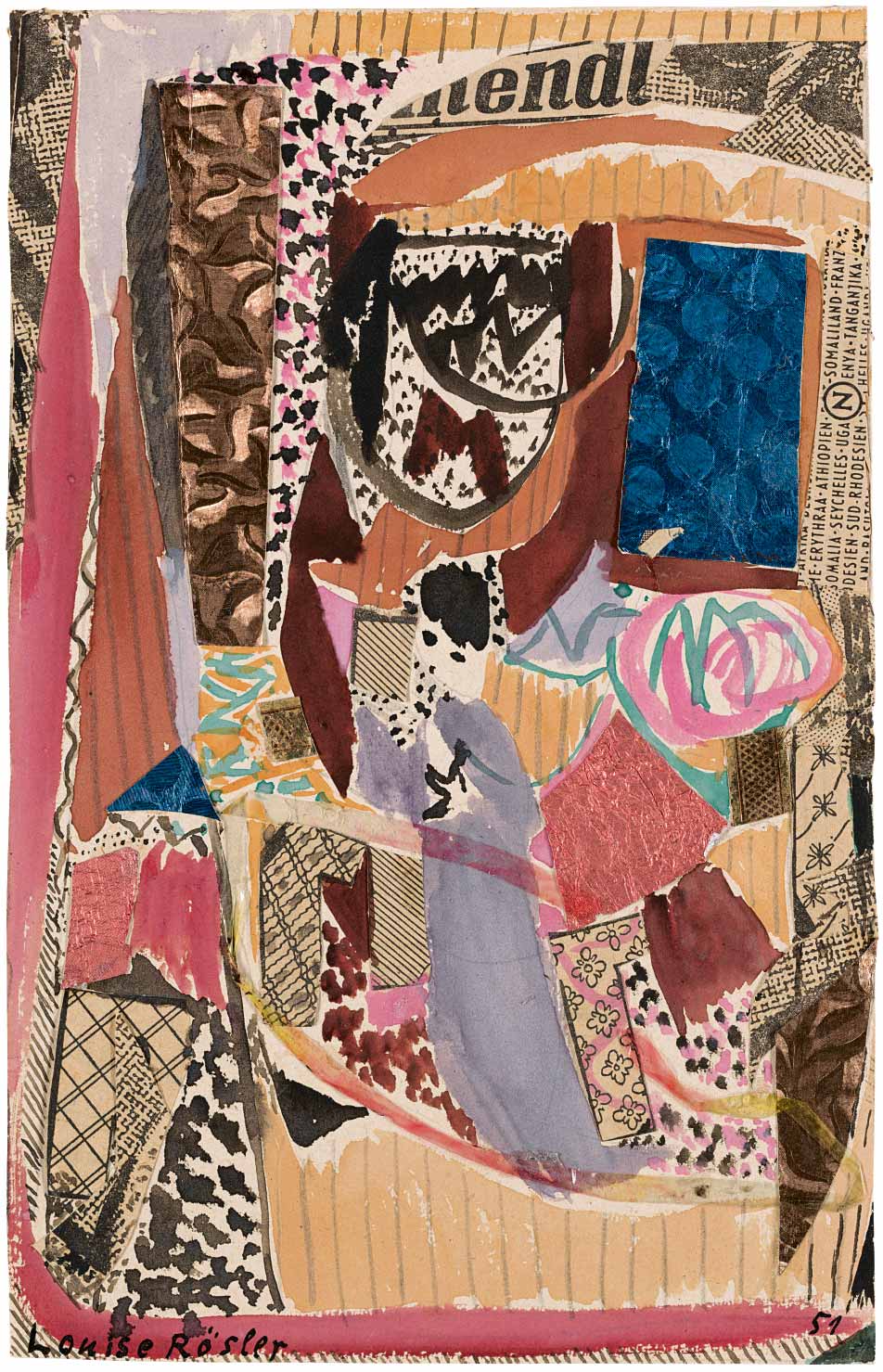

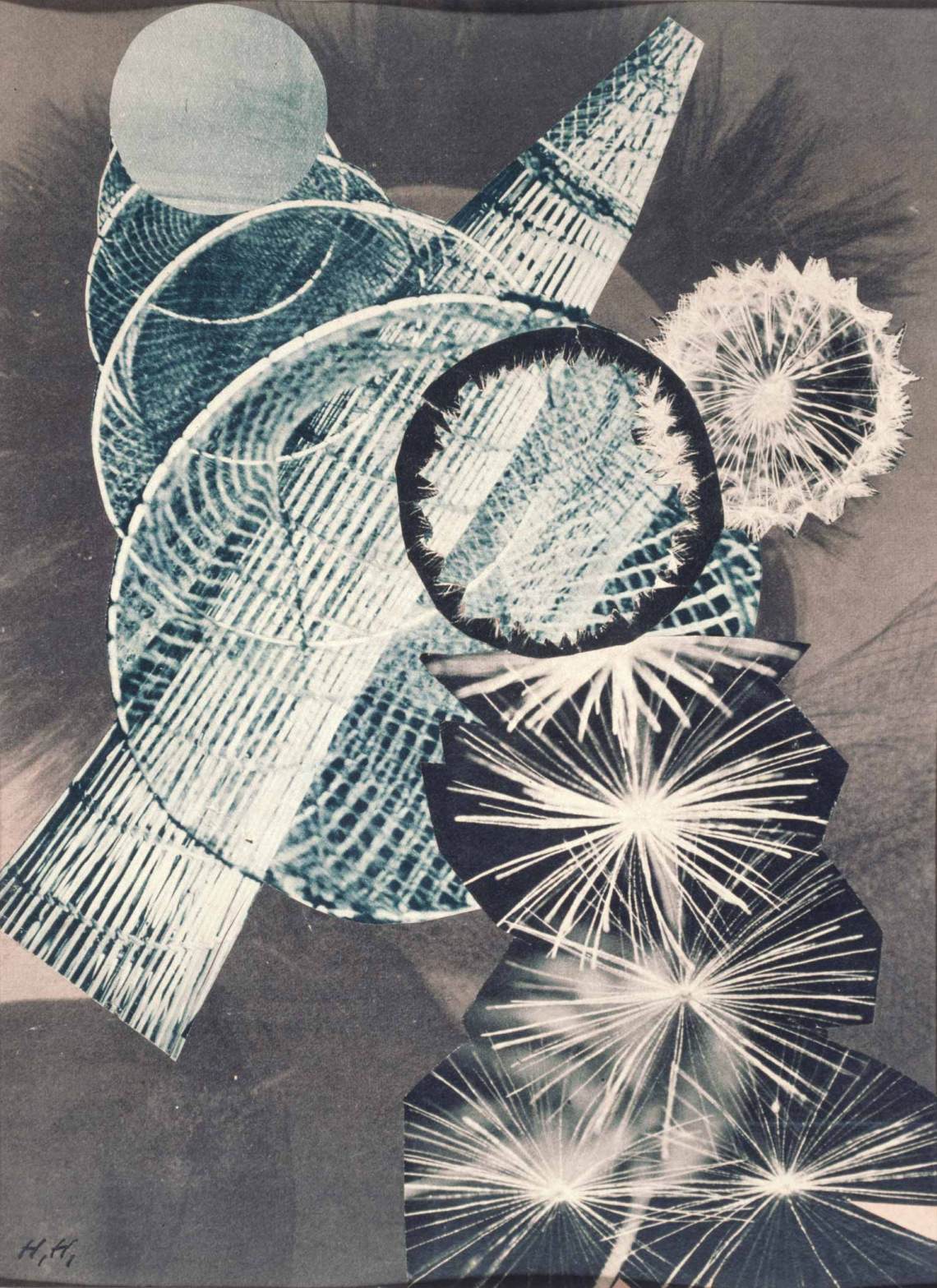

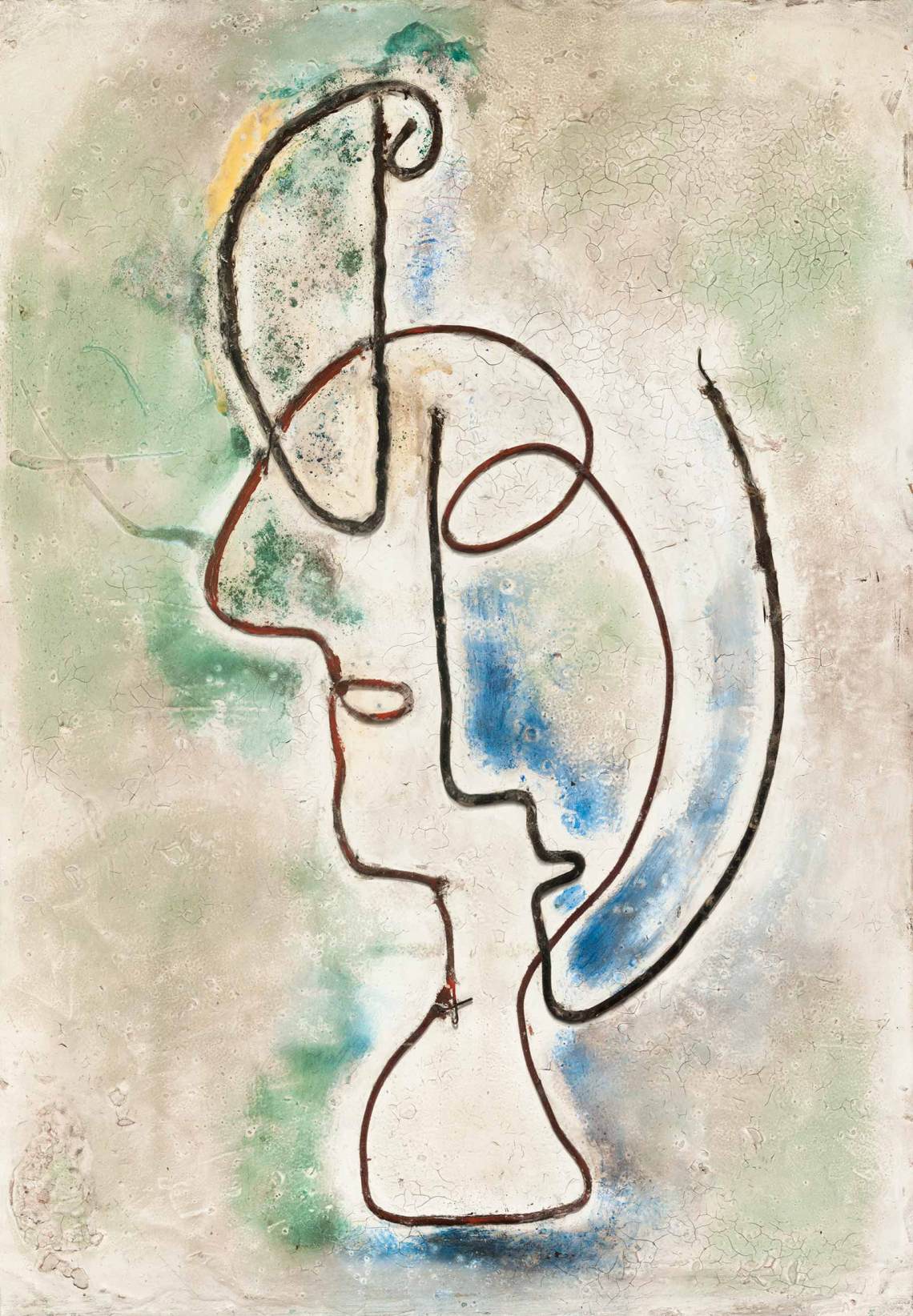

Against this fierce bleakness, we encounter streaks of optimism, even early on—often, notably, from women artists. Louise Rösler’s small-scale earlier works, including Frankfurt Main Station (1943) and her watercolor Frankfurt in Rubble (1947–1948), transmit, through the density of images and, in the latter case, an almost vernal handling of watercolor, an aura of hope. Her use of discarded materials like candy wrappers (as in her delicious 1951 collage The Room) brings a touch of amused and ironic glitter to her work, along with a sense of playful possibility. Jeanne Mammen, with her Picasso-esque abstracts and heads, adopts, in Untitled (Abstract Composition) (1950), a pastel palette with flecks of golden yellow that give off light. And Hannah Höch’s Untitled (Miniatures) express, with Klee-like whimsy, a complex range of emotions as much joyful as grim. Her largest work in the exhibition, a collage entitled Beautiful Fishing Nets (1946), is indeed beautiful: though not colorful, it plays on spirals and firework-like emanations that resemble—and may even be photographs of—dandelion clocks. This could be interpreted as a series of wartime explosions, with a rocket scything across the frame, but as the title indicates, the effect is instead vibrant and optimistic—a visual translation of “make love, not war.”

Such optimism is integral to “Inventur.” As one unnamed artist explained to the curator Charlotte Weidler in 1951: “We don’t want any more destruction. Our view of life is a hopeful one.” Gustav Deppe’s Industrial Plant and High Voltage Picture (both 1949) take an abstracted approach to the increasingly industrialized Ruhr area where he lived, “a kind of inventory of the industrial reality” that nonetheless allows for wit. Hann Trier’s 6 Color Woodcuts (1950)—made from tennis racket cases he discovered in his attic while hunting for firewood—have the appearance of brightly colored human fetuses waiting to be born. Karl Hartung’s Moore-like sculpture Striding (1950), born of the artist’s belief that “today man is fundamentally different from what he has ever been before,” embodies a vigorous optimism in the wake of disaster.

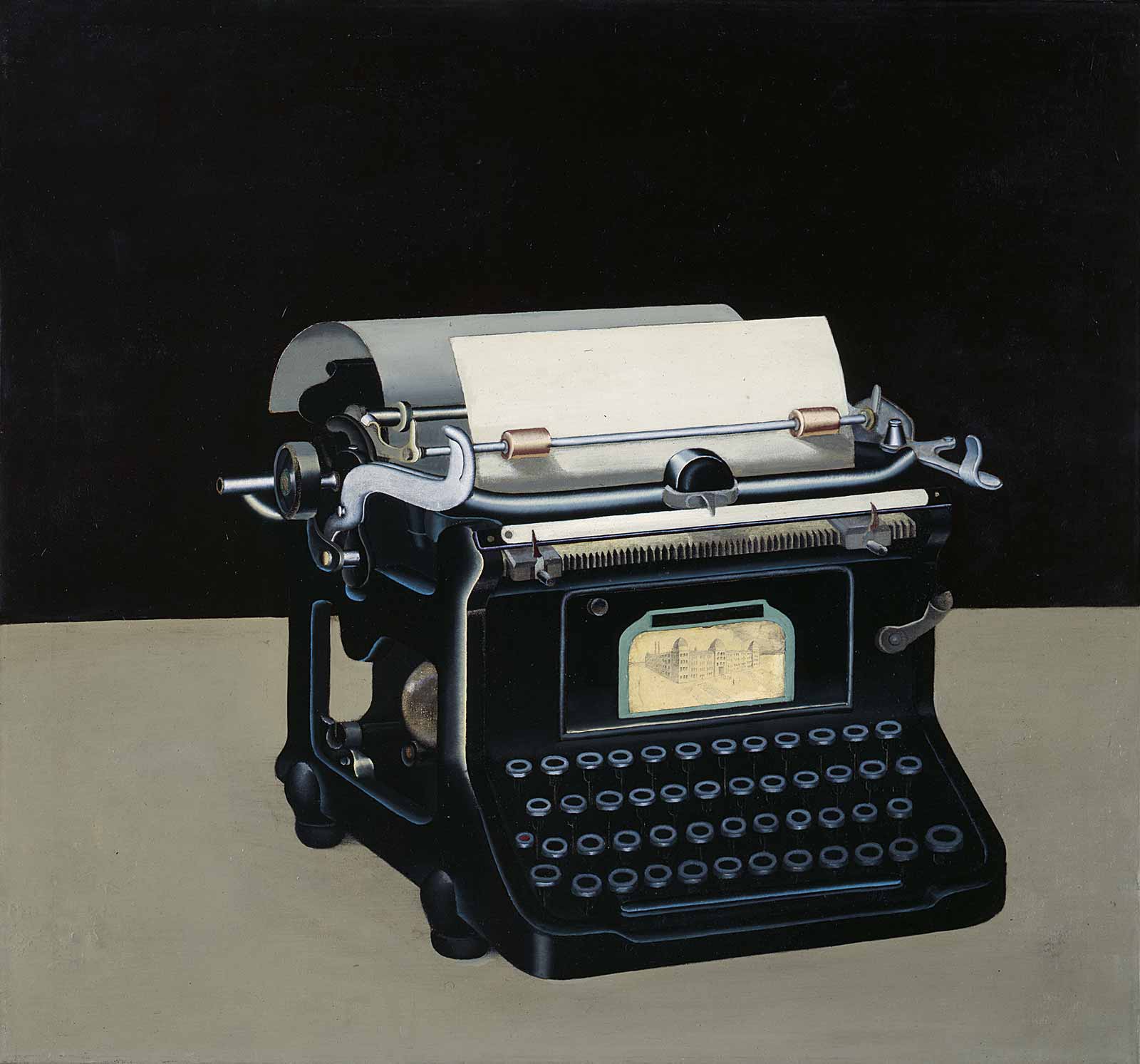

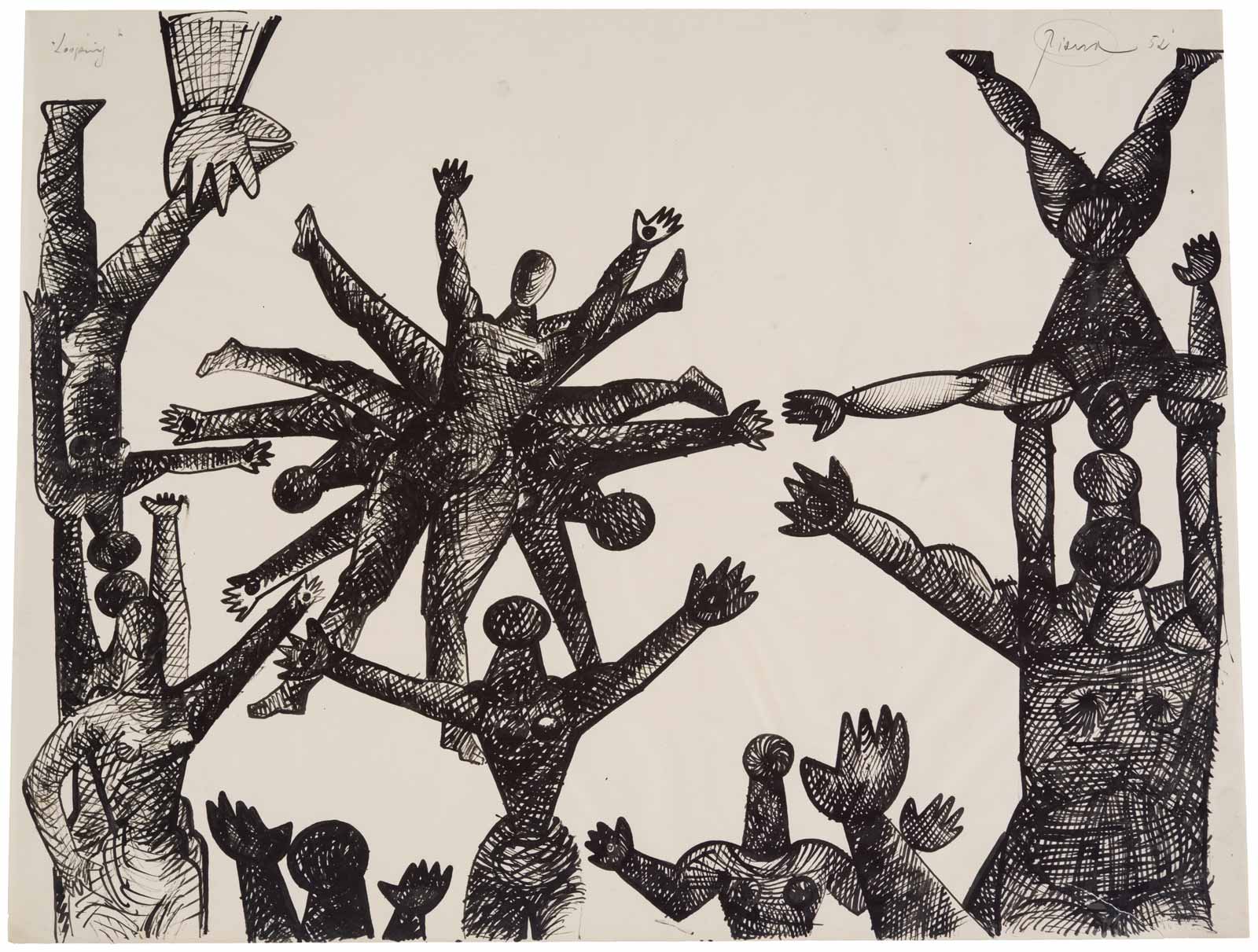

By the time of the first documenta contemporary art show in Kassel in 1955, an evolution was well underway: Konrad Klapheck completed Typewriter (1955), his first “machine picture,” a still-life of a rented Continental brand typewriter, which is considered to be a precursor of Pop art. Ernst Wilhelm Nay’s vital large painting Embers (1951) and Otto Piene’s Flying People (1952) include echoes of the past, but seem, above all, to look ahead. Piene’s acrobats, writes Jungmin Lee in the catalogue, “evoke the sun, an icon that Piene repeatedly referred to as symbolizing ‘zero’ or a ‘new beginning’ in his work.” Hans Uhlmann’s Constellation (1956), a suspended sculpture, similarly expresses a sort of Jetsons-like futurism. Even as it “oscillates between organism and industrial construction,” Uhlmann’s piece evokes, in hindsight, a particular, recognizable step on the consciously sanguine path forward that Germany took out of terrible darkness into the second half of the last century.

“Inventur—Art in Germany, 1943–55” is on view at the Harvard Art Museums through June 3.