This is the third in a series featuring past highlights of The New York Review, to celebrate the magazine’s fifty-fifth anniversary.

“In 1969, the Year of the Pig, participants in what is known as (descriptively) youth culture or (smugly) hip culture or (incompletely) pop culture or (longingly) the cultural revolution are going through big changes,” Ellen Willis begins, writing at the end of that year on Dennis Hopper’s film Easy Rider and Arthur Penn’s Alice’s Restaurant. Willis identifies “a pervasive feeling that everything is disintegrating, including the counter-culture itself.” Her essay is at once a contemporary report on the state of American culture and a retrospective look at the Sixties, grappling with what she calls “the overpowering sense of loss, the anguish of What went wrong? We blew it—how?”

In 1970, Jason Epstein, one of The New York Review’s founders, filed a long report on the trial of the Chicago Seven, charged in federal court with conspiracy and incitement to riot at the 1968 Democratic National Convention. Allen Ginsberg took the stand as a witness; his testimony included chanting the Hare Krishna mantra over the objections of government lawyers, the playing of a harmonium, and the recitation of poems by Blake and Whitman as well as his own “Howl.”

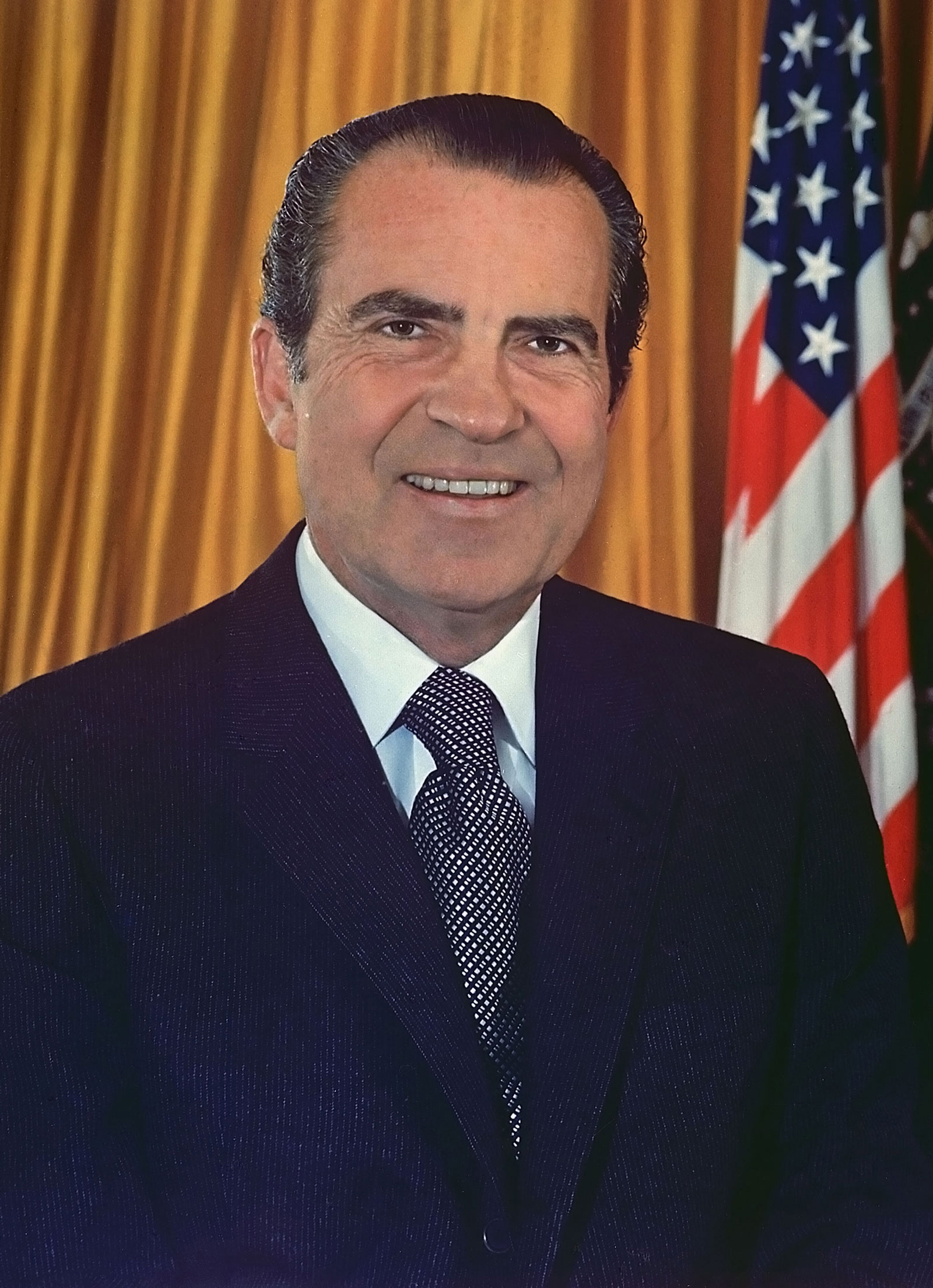

In the third selection below, published in the Review in the fall of 1971, Hannah Arendt considers a subject of some relevance to our present era: lying in politics.

1969

See America First

Ellen Willis

(University of Minnesota Press), courtesy of Ellen Willis’s family; click to enlarge

Neither Easy Rider nor Alice’s Restaurant ever considers a political solution to the social chaos. The most Guthrie can conceive of is individual resistance; he wonders at one point whether he would have the courage to refuse induction. Fonda and Hopper never think politically at all. The temptation is to credit the media with a sinister plot to give the impression that there is no alternative to individualism, but that is a convenient copout. In private life Guthrie, Fonda, and Hopper are all more or less apolitical and the movies reflect their personalities. Furthermore I’m not at all sure that their attitude is not shared by the majority of adherents to the hip life style. It may be that those of us who still have some faith in collective action are simply indulging an insane optimism. Nevertheless, it is clear to me that if we want to survive the Seventies we should learn to draw strength from something more solid than a culture that in a few years may be just a memory: “Remember hair down to your shoulders? Remember Janis Joplin? Remember Grass, man? Wow, those years were really, uh, far out!” »

1970

The Chicago Conspiracy Trial: Allen Ginsberg on the Stand

Jason Epstein

THE COURT: I have admonished you time and again to be respectful to the Court. I have been respectful to you.

MR. KUNSTLER: Your Honor, this is not disrespect for anybody but—

THE COURT: You are shouting at the Court.

MR. KUNSTLER: Oh, your Honor—

THE COURT: Shouting at the Court the way you do—

MR. KUNSTLER: Everyone has shouted from time to time, including your Honor. This is not a situation—

THE COURT: Make a note of that, please. I have never,—

MR. KUNSTLER: Voices have been raised—

THE COURT: I never shouted at you during this trial.

MR. KUNSTLER: Your Honor, your voice has been raised.

THE COURT: You have been disrespectful.

MR. KUNSTLER: It is not disrespectful, your Honor.

THE COURT: And sometimes worse than that.

THE WITNESS: O-o-m-m—m.

[A climactic moment in Ginsberg’s testimony. Mr. Kunstler had indeed raised his voice, so had Judge Hoffman. The atmosphere was extremely tense, with marshals on the alert and the courtroom itself verging on chaos. Suddenly Ginsberg began to chant and the courtroom was instantly silenced.]

THE COURT: Will you step off the witness stand, please, and I direct you not to talk with anybody about this case or let anybody speak with you about it until you resume the stand at two o’clock, at which time you are directed to return for further examination.

MR. KUNSTLER: He was trying to calm us down, your Honor. »

1971

Lying in Politics: Reflections on The Pentagon Papers

Hannah Arendt

When we talk about lying, and especially about lying among acting men, let us remember that the lie did not creep into politics by some accident of human sinfulness; moral outrage, for this reason alone, is not likely to make it disappear. The deliberate falsehood deals with contingent facts, that is with matters which carry no inherent truth within themselves, no necessity to be as they are; factual truths are never compellingly true. The historian knows how vulnerable is the whole texture of facts in which we spend our daily lives; it is always in danger of being perforated by single lies or torn to shreds by the organized lying of groups, nations, or classes, or denied and distorted, often carefully covered up by reams of falsehoods or simply allowed to fall into oblivion. Facts need testimony to be remembered and trustworthy witnesses to be established in order to find a secure dwelling place in the domain of human affairs. »

Advertisement