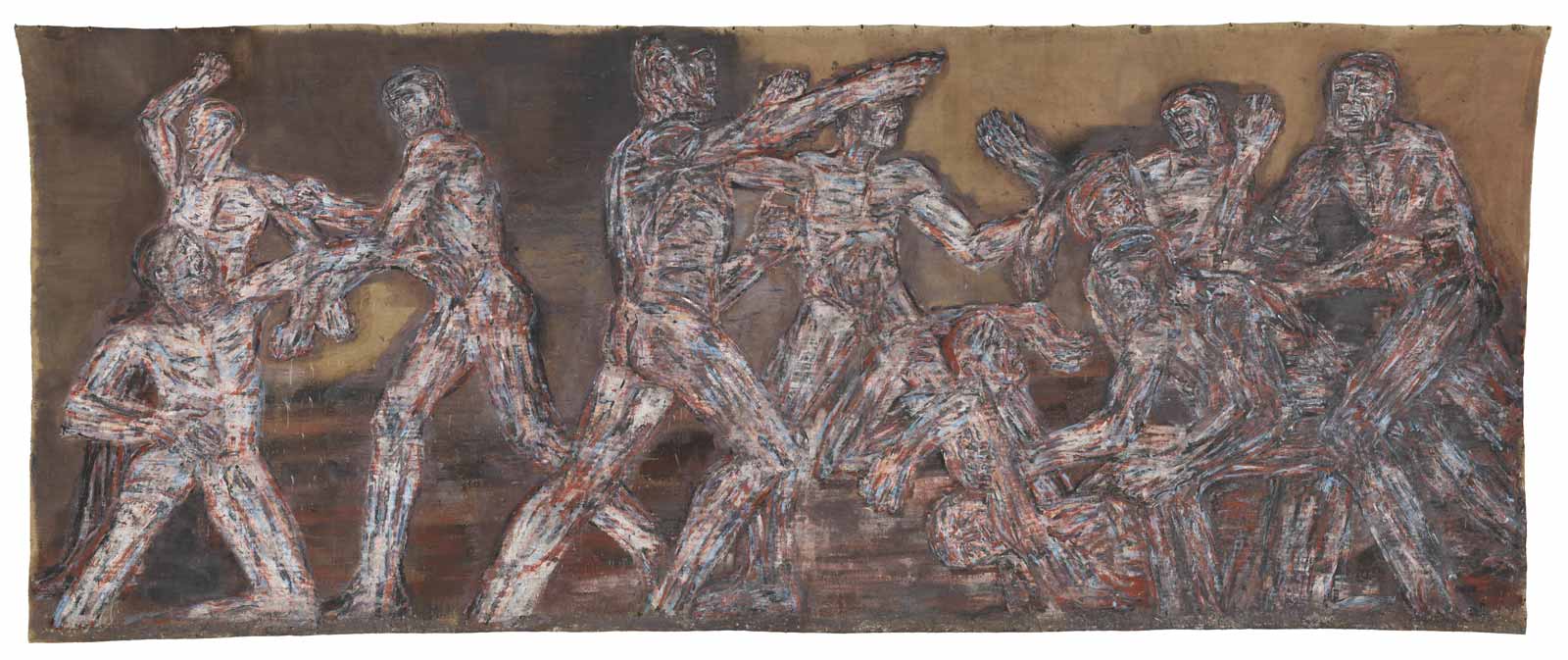

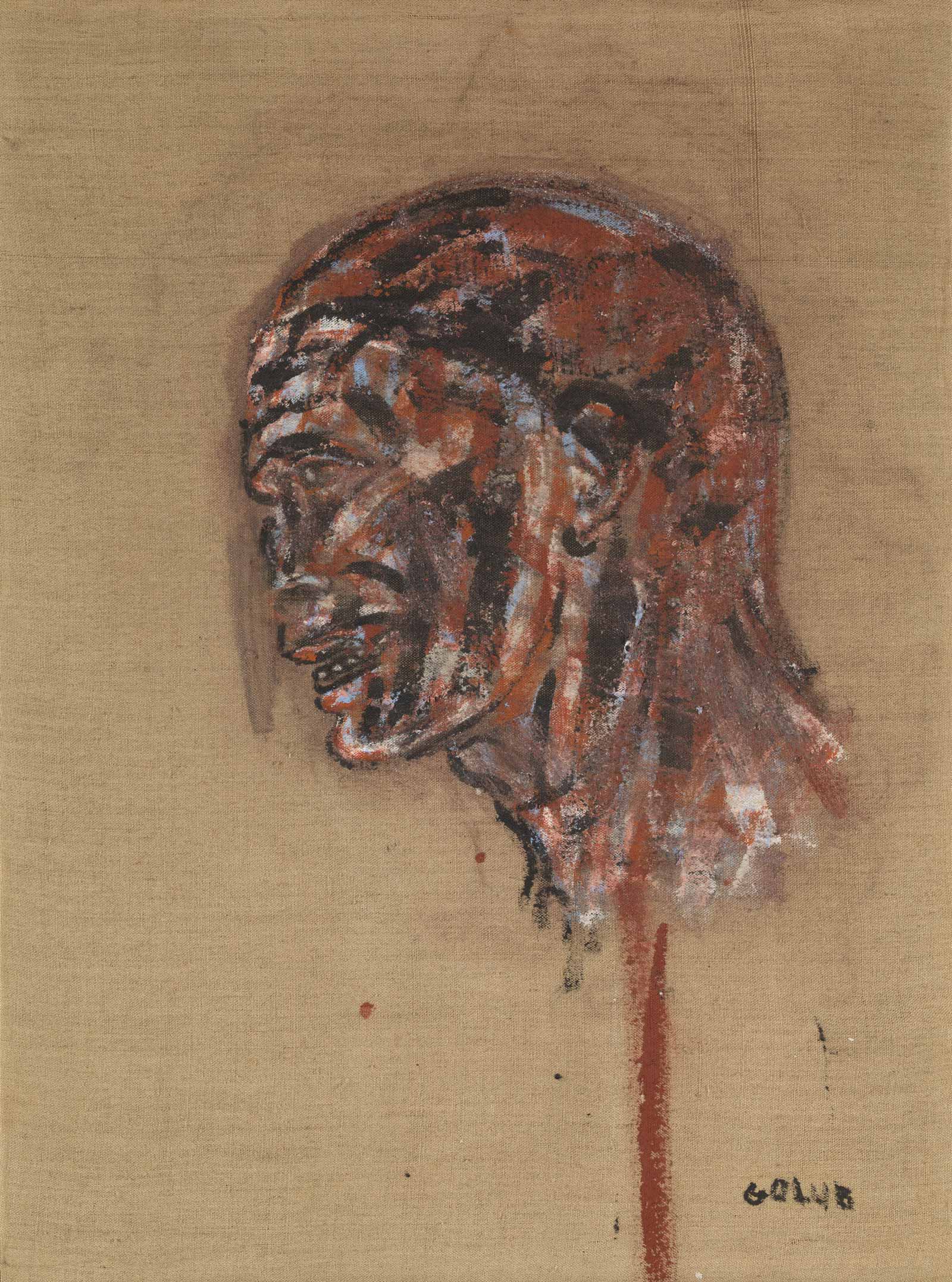

Leon Golub sometimes said he painted monsters, but mostly he painted men. In Gigantomachy II (1966), the huge, scabrous centerpiece of “Raw Nerve,” a selective survey of Golub’s work now at the Met Breuer, ten men entangle themselves in an awkward melee, their bodies unclothed but not quite naked—napalmed, maybe, would give a better sense of it. The artist bullied his canvases, scraping, flaying, and pounding their surfaces—legendarily with a meat cleaver. He favored the hues of wounds: blood reds, bruised blues, the tones of cauterized flesh. The unprimed linen canvas for Gigantomachy II, unframed and ten feet tall, resembles the beaten skin of a giant’s war drum.

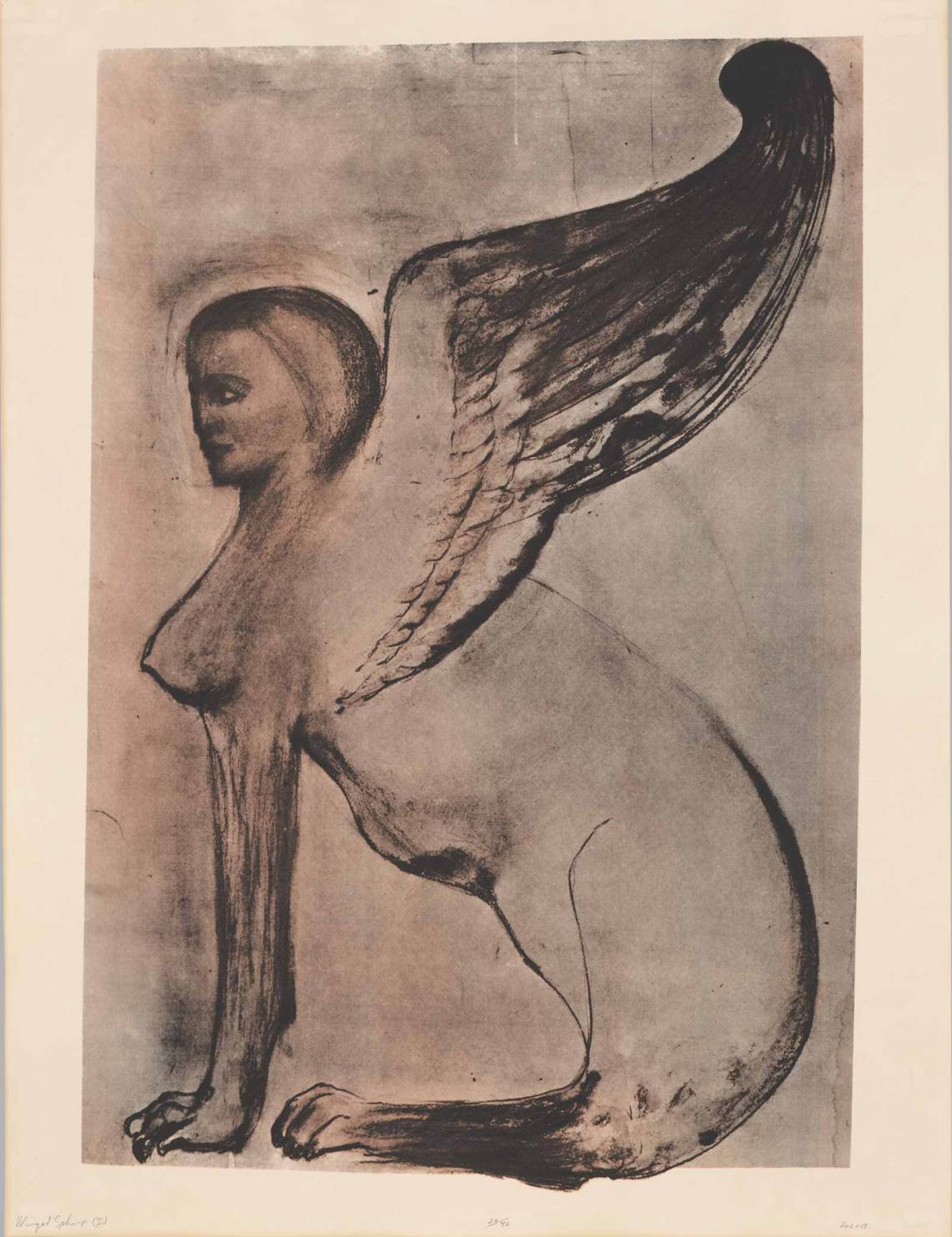

“Raw Nerve,” which spans seven decades and comprises mostly lesser-known paintings, drawings, and lithographs, shows the painter’s affinity for antiquity, juxtaposing his tableaux of soldiers, mercenaries, and other powerful men with the traditions of ancient Roman and Greek art, as well as other classical genres. Although their scale references early history paintings, which typically sought to heroize characters from a specific past, Golub’s works repeatedly portray men enacting violence in settings mostly stripped of period detail, as if to suggest that history itself can be reduced to men behaving cruelly.

Born in 1922, Golub knew he wanted to become an artist as a teenager, standing in front of Guernica for the first time when it traveled to Chicago. Picasso’s grim horizon, with its consuming dimensions and political urgency, would help orient Golub throughout his career. After serving in World War II as a cartographer, he began to paint alongside a loose collective of Chicagoans known as the Monster Roster, whose work, through allusions to mythology and existentialism, evoked an acrid postwar futility. It was at this time that he met Nancy Spero, a feminist and antiwar artist whom he married in 1951.

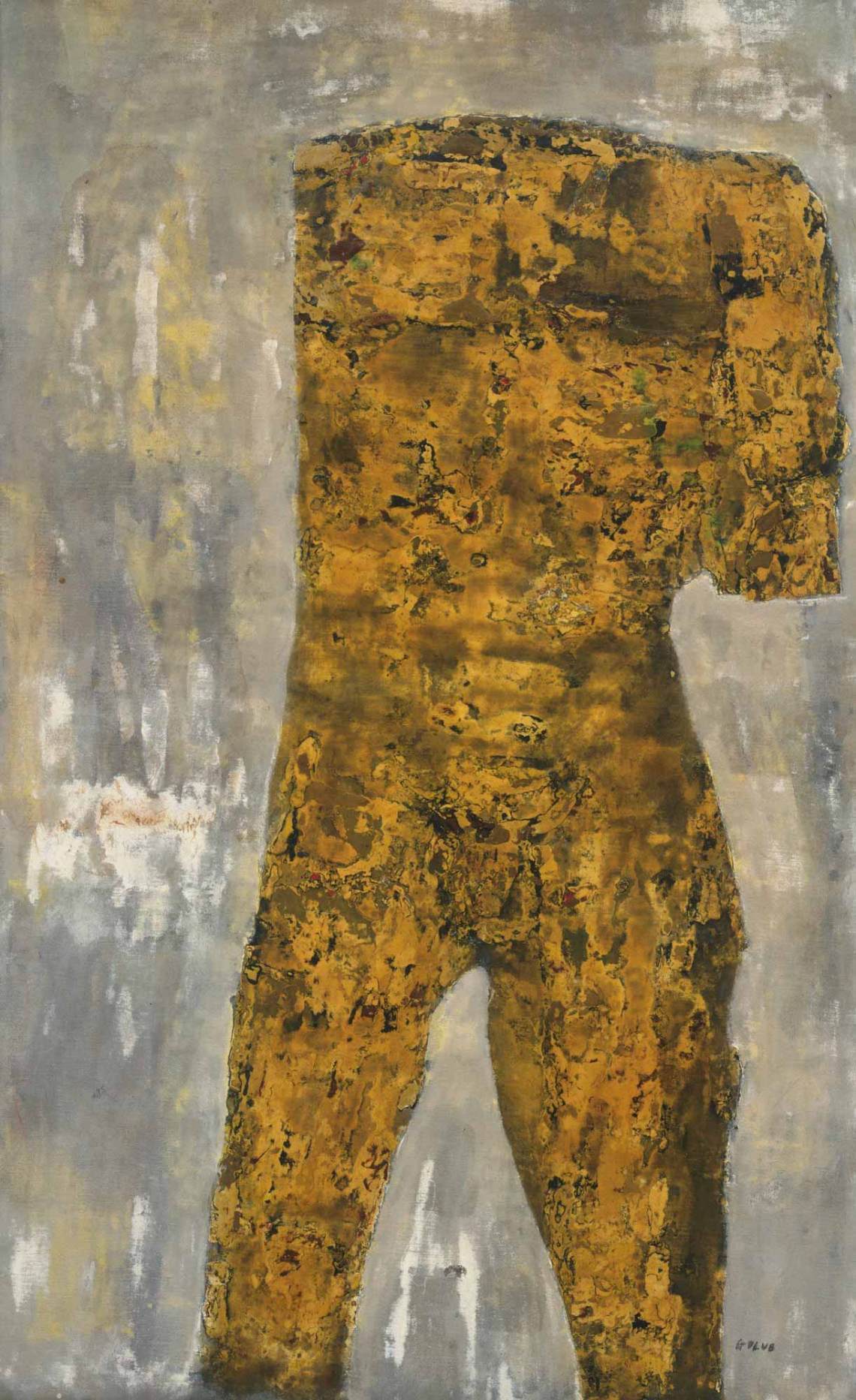

Golub then resettled for a few years in Europe, where he took in the vestiges. One can already see him engaging with archaic traditions in the first gallery, most startlingly in a 1960 lacquer painting of a torso inspired by the ruins at the Great Altar of Pergamon (its frieze inspired his five-painting Gigantomachy series). A charred stump of a man that glistens with caked golds and blues, the torso recalls Rilke’s description of Apollo, “suffused with brilliance from inside,/like a lamp, in which his gaze, now turned low,/gleams in all its power.”

As Golub learned, power blinds. During the Vietnam War, he and Spero joined the Art Workers’ Coalition, alongside organizers like Lucy Lippard and Robert Morris, to protest art museums they considered complicit in war and injustice. In 1969, the Coalition picketed museums like the Guggenheim, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art for their administrative indifference to the conflict in Vietnam. The group, in addition to pressuring these venues into addressing the war in their programming, demanded free admission and an initiative for community inclusion.

In 1970—the same year Golub painted the head of a Vietnamese person impaled on a pike rendered with one cherry-colored brushstroke—members of the Coalition demonstrated in front of Guernica at MoMA in an effort to persuade Picasso to retract the painting. As long as the piece was displayed in an institution refusing to challenge corruptions of power, the Coalition figured, its political value was emptied. Unfortunately, the Met Breuer exhibition does little to elaborate this history with grassroots activism. Golub’s reservations about the art world and his place in it obliquely inform works like the unrepresented Interrogation and Mercenaries series from the Eighties. These images, whose characters often lock eyes with the beholder, reckon with both the moral duty and failures inherent in being a witness to the world. Looking at his paintings, one cannot help but feel like a bystander.

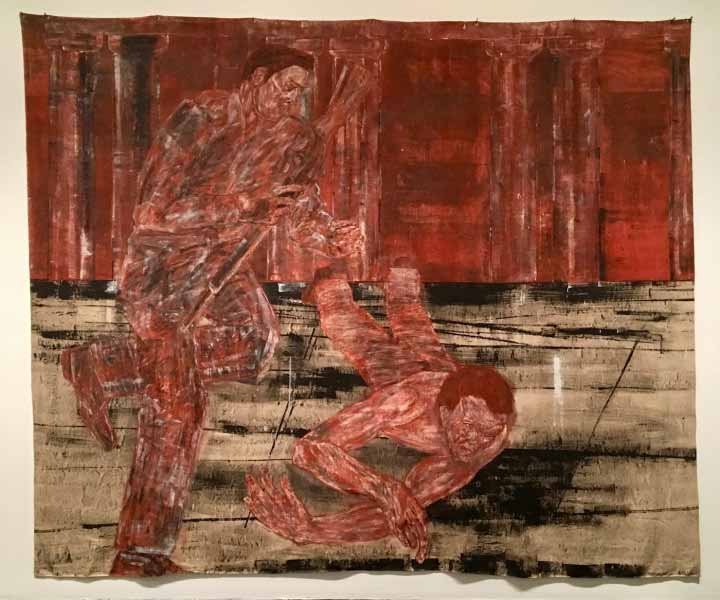

Abstraction vexed him. He saw it as irresponsible amid so much turmoil. In 1966, when Golub was starting his Gigantomachy series, Barnett Newman was painting canvases of similar scale almost completely red. Golub would later incorporate this kind of Color Field painting into his scenes of brutality, as in his White Squad series (1982–1987), eleven paintings that depict Salvadoran death squads standing in front of bright red voids, their victims often on the ground, recumbent. This project is represented here solely by White Squad VIII (1985), where an armed mercenary marches toward his target, a man who seems to be attempting to squirm out of the canvas, rinsed almost entirely in dark ruby. The victim’s face—agonized and crumpled—betrays the compassion that animates Golub’s paintings. It’s humans that have, more than any other species, the vastest capacity for violence as well as empathy, an equipoise Golub interpreted with queasy ambivalence.

Advertisement

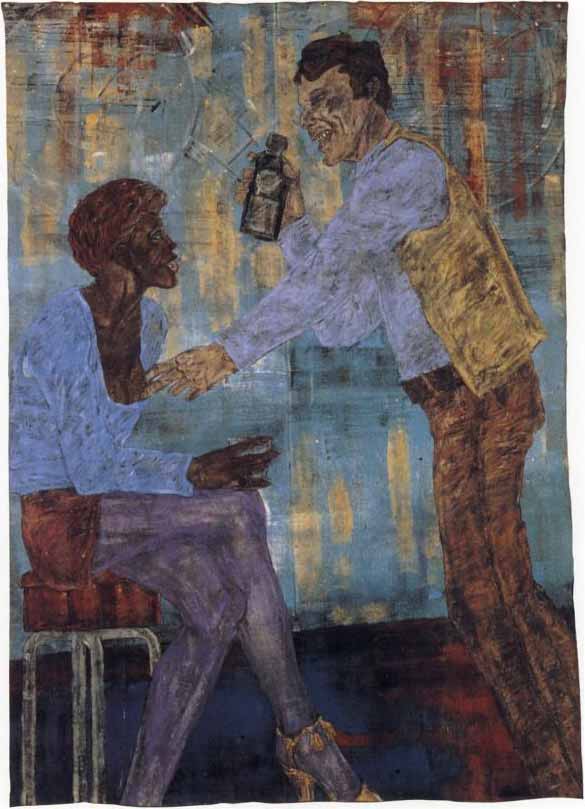

Less fatal encounters are also staged. In a 1986 work nearly the size of a billboard, two black women wait on a bench placed in front of a beige square. One looks up at a white man who is loitering against a pastel blue wall, his head angled away, a gesture of committed ignorance—or is it evasion? Another work, from 1983, introduces us to a ghoulish mercenary. His right hand holds a bottle, his left reaches toward a seated woman’s breast. The wallpaper is a smeared grid of blue and yellow. Perhaps Golub worked closer to the modes he disdained than he realized. If the people he depicted were to walk (or crawl) out of the frame, the viewer would be left with Abstract Expressionist objects, the frustrations and frictions between people dissolved, the works reduced to decor.

Golub died in 2004. In his later efforts, to which the show devotes a room, the paint is less layered, the canvases emptier. We find small, erotic nudes; sparser vanitas; a smattering of menacing phrases alongside figures and on pages in vitrines. The unfinished quality of these works perhaps owes less to a spiraling cynicism than to the limits of an aging artist. A sense of overall incompleteness is underlined by curatorial misjudgments; because this selection tries to represent a bit of everything, it’s difficult at times to grasp how pieces within a series relate to one another.

Nevertheless, the decision to hang Gigantomachy II at what is both the exit and entrance of the exhibition—immediately confronting one with its thrashing limbs and contorted faces—feels necessary. The word gigantomachy means a struggle between gods and giants, but revisiting them at the end, battle unresolved, the figures don’t seem godly at all. Only human.

“Leon Golub: Raw Nerve” is at the Met Breuer through May 27.