Why do mirrors appear so often in Victorian paintings? “Reflections: van Eyck and the Pre-Raphaelites,” recently at London’s National Gallery, suggests an answer. In 1842, Jan van Eyck’s The Arnolfini Portrait (1434) arrived in the gallery. The collection’s first example of early painting from the Low Countries, it caused a sensation with its jewelled colors, precise detail, and careful brushwork, its solemn couple surrounded by an array of symbolic objects. Behind them, a circular mirror showed two men entering the room, implying a world outside the painting, a story not told. Within a week, the painting was copied, badly, in a woodcut for The Illustrated London News, starting a new interest in “Netherlandish” art.

At the time, the Royal Academy Schools occupied the east wing of the gallery, and students were encouraged to admire the collection, particularly the grand Renaissance paintings. But to three students—John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti—the gestures and style of the Renaissance seemed empty and overblown, and by contrast the quiet intensity of van Eyck was a revelation. In 1848, they formed the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Their stated aims, expressed in their magazine The Germ in 1850, were to express genuine ideas, to study nature, “to sympathise with what is direct and serious and heartfelt in previous art, to the exclusion of what is conventional and self-parodying and learned by rote.” In their work, a concern for the “pure” art of the distant past would be combined with subjects from modern life and literature.

Van Eyck’s painting gave them a model, a touchstone, encouraging their painstaking depiction of detail: the gloss on a curl of hair, the pattern in a carpet, the shimmer of a mirror. The curators of the current show note that this interest in verisimilitude coincided with the contemporary fascination with photography, then a new medium, where the curved lens rather than the curved mirror is the “eye” of the artwork. In 1843, a critic in the Athenaeum journal noted that the enriched details of the room in The Arnolfini Portrait “seem to be daguerreotyped rather than painted, such is their extreme fineness and precision.” In an intriguing juxtaposition, the exhibition places a set of daguerreotypes next to Millais’s uncharacteristically formal, even primitive-looking Mrs James Wyatt Jr and her Daughter Sarah (circa 1850), in which the precision of the foreground stands out against prints of Renaissance paintings on the wall behind.

Millais’s debt to van Eyck is clear in his Mariana (1851), with its bed, its censer and glowing lamp, and the rich color of her dress—one preliminary sketch even includes a small round mirror behind the heroine’s head. In Holman Hunt’s The Awakening Conscience (1853), the large mirror on the rear wall reflects a garden we cannot see, the place of innocence that haunts the woman’s mind as she gazes toward it, rising from her lover’s lap. Every detail bears some symbolic weight, asking both for judgment and sympathy: the encased clock, the cat with its prey, the dropped glove, and the music, rendered so clearly that one can read the titles of Thomas Moore’s ballad, “Oft in the Stilly Night,” and Edward Lear’s setting of Tennyson’s “Tears, Idle Tears” on the carpet, whose pattern gestures back to van Eyck again.

The complexities of this painting point to Hunt’s own tumultuous feelings toward the model, Annie Miller. A decade later, reworking his painting Il Dolce Far Niente (1859–1866;1874–1875), he scrubbed out Annie’s head and replaced it with that of his fiancée, Fanny Waugh: the convex mirror gleams behind her, suggesting a different pose, a deepened space of art and domesticity, lit by a glowing fire.

Hunt also paid homage to van Eyck in his drawing of Tennyson’s “The Lady of Shalott.” Cursed if she looks through the window down to Camelot, she can see the outside world only in reflections, which she transfers to her loom: “But in her web she still delights/To weave the mirror’s magic sights.” When she finally turns, entranced by the sight of Sir Lancelot riding by,

Out flew the web and floated wide;

The mirror cracked from side to side;

‘The curse is come upon me,’ cried

The Lady of Shalott.

In a preliminary drawing, Hunt showed her entwined in the loom’s thread, and he encircled the round mirror with smaller roundels telling the story. A few years later, in his lavishly decorative painting of 1857—in which the Lady has kicked off wooden pattens (overshoes) that come straight from the Arnolfini painting—the mirrored knight is matched by religious imagery. For Hunt, the Lady was an artist who abandons her mission when she gives in to her desires. By contrast, in Lizzie Siddal’s little drawing, where the thread breaks in waves toward the shattered mirror, the Lady seems a figure of touching loneliness and longing. Later interpretations darkened the theme: in John William Waterhouse’s 1894 rendering, she stoops and peers against a sunlit, mirrored scene; in Sidney Meteyard’s 1913 painting, the Lady, languid and weary, closes her eyes to the dimly reflected lovers. Increasingly, the mirror images appear more like psychological studies than poetic meditations. In Edward Burne-Jones’s mesmerizing portrait of his daughter, Margaret Burne-Jones (1885–1886), the glass hangs like a dark halo, an image of a distorted world.

Advertisement

The Arnolfini Portrait’s own early history also figures in the exhibition. In the sixteenth century, the painting entered the Spanish royal collection. Later, during the Peninsular War, it was included in the loot captured from Joseph Bonaparte’s baggage train at the Battle of Vitoria in 1813, and was “found” by the Scottish soldier James Hay, who eventually sold it to the National Gallery. Velázquez saw the painting when it was in Madrid, and it is often suggested that this prompted the famous mirror in Las Meninas, or The Family of Philip IV (circa 1656), holding the shadowy, reflected presence of the King and Queen. The current exhibition includes the partial copy of Velázquez’s painting made in 1862 by the Scottish artist John Phillip, which was hung in the Diploma Gallery at the Royal Academy, another mirror to inspire another student generation.

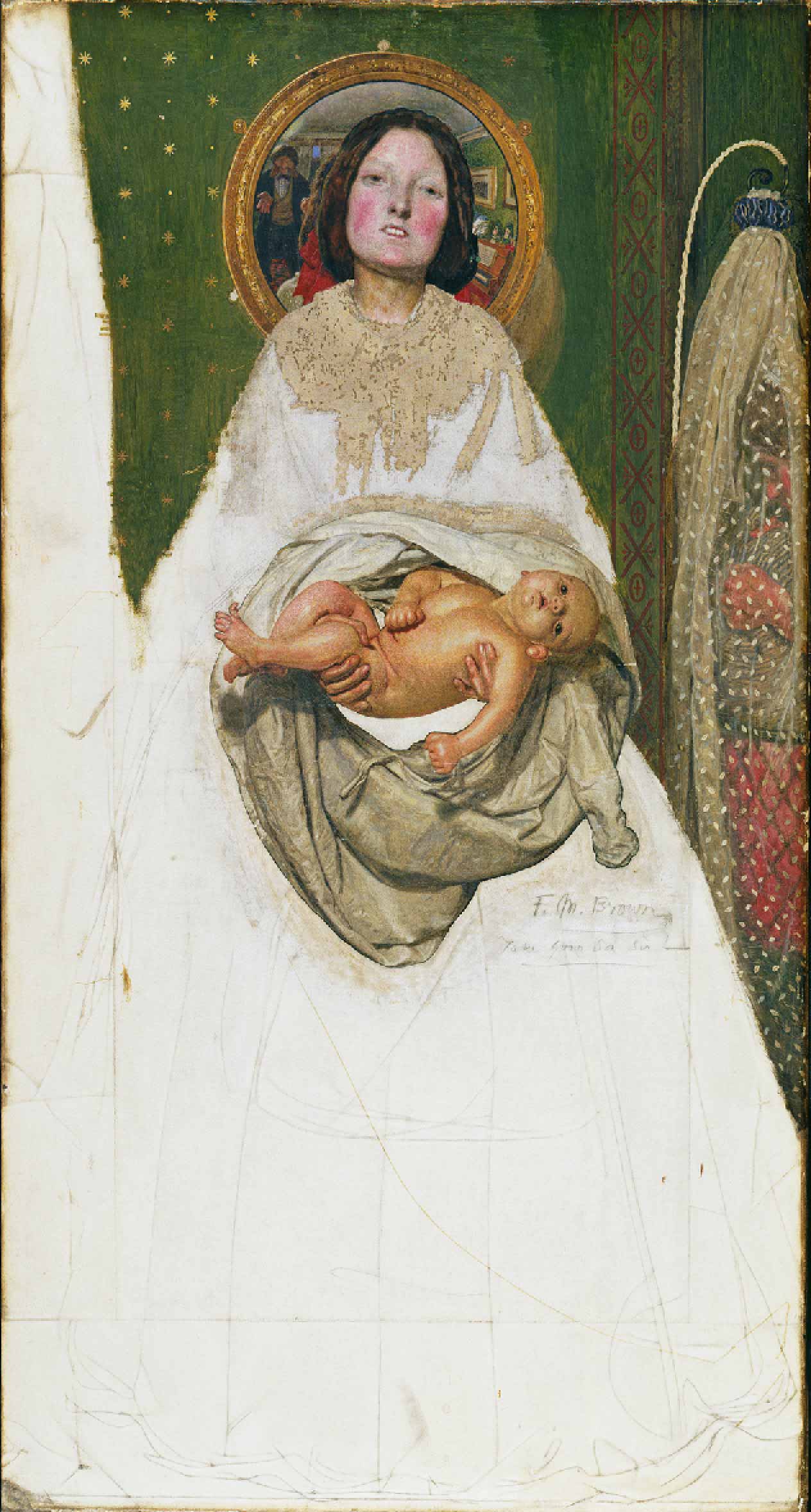

This is not a show of equals—the genius of van Eyck and the implied Velázquez blazes out in comparison to the Victorian works. Instead, the exhibition, beautifully curated and arranged, is more like an illustrated essay, its tight focus on the single detail of the mirror illuminating the lesser artists’ relationship to tradition. Part of the curious pull of these paintings derives from our knowledge that “real” mirrors, or accurately depicted ones, centrally placed, would reveal the artists themselves, in tune with the Pre-Raphaelites’ preoccupation with their Romantic inheritance, which placed the artist and his drama very much at the center of the art. Sometimes, this is the case: William Orpen’s The Mirror (1900) shows his then-fiancée, the Slade model Emily Scoble, solemn beneath her flowery hat: beside her in the mirror, Orpen appears, but with another woman by his side. More often, the artists ask us to see the image they are “reflecting on”—whether it be from a poem or from domestic life, like the father with his arms outstretched in Ford Madox Brown’s Take your Son, Sir! (1851–1892), left brutally unfinished when his small son died. And, of course, as we stand before the pictures, a real rather than painted mirror would reflect ourselves, the viewers, the audience. Bending back the painted light, the mirror reminds us of our presence as witnesses. Beyond that, it points to the slippery relationship between “realism” and imaginative representation, from van Eyck’s time to today.

“Reflections: van Eyck and the Pre-Raphaelites” was at London’s National Gallery from October 2, 2017, through April 2, 2018.