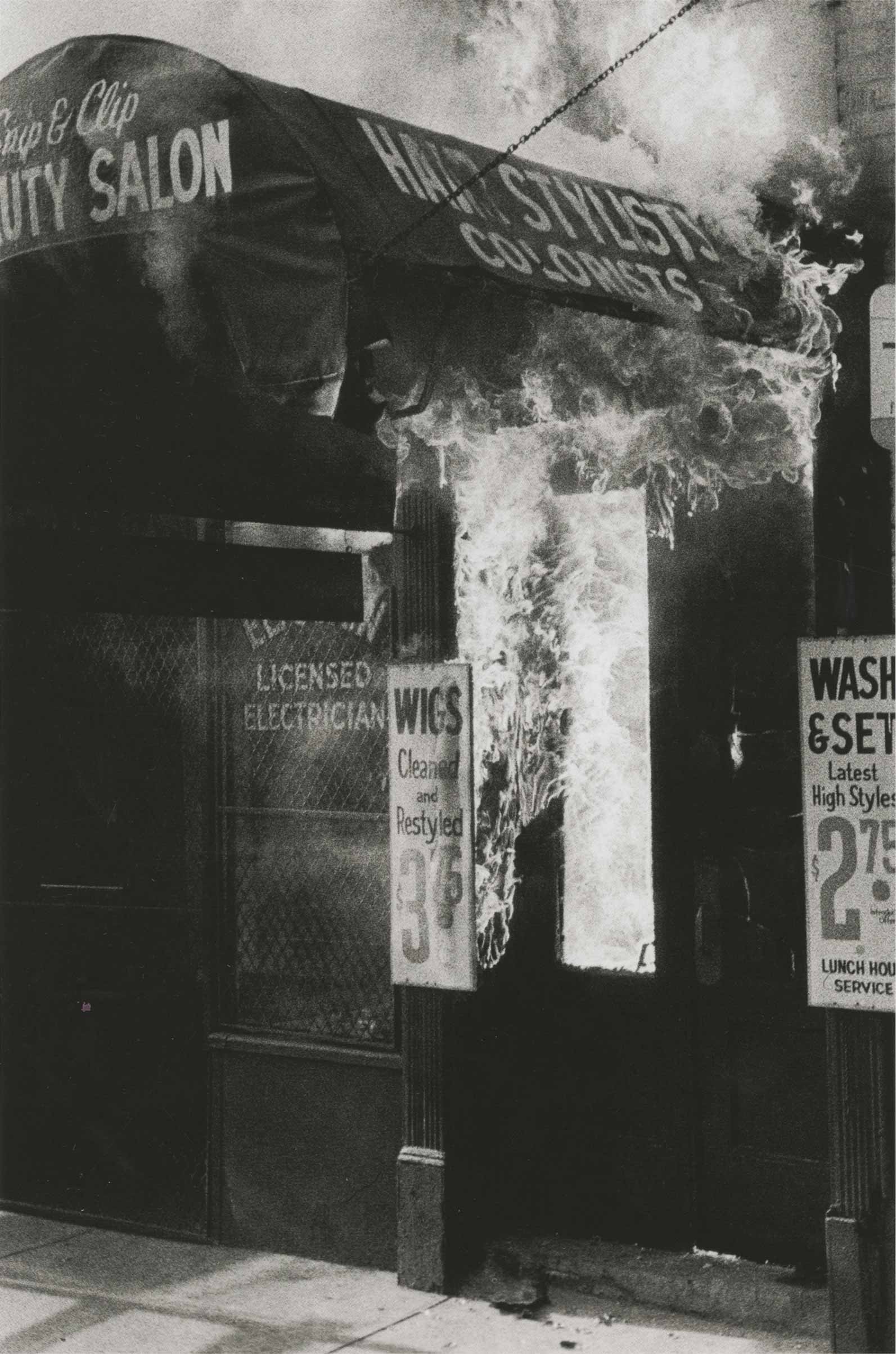

It happened in 1968. Ralph Gibson, a young photographer who had recently moved to New York from California, was walking down 6th Avenue when he saw a beauty salon engulfed in flames. That image, of flames devouring the awning and storefront—which, ironically, also had a sign boasting a “licensed electrician”—below a halo of billowing smoke obscuring the sky, would become one of the most arresting photographs in his first book, The Somnambulist (1970).

It also demonstrates how Gibson’s images are deeply tied to the symbolic and the subconscious: his mother, whom he credits as the greatest creative influence in his life, had died a few years before in a fire that destroyed the beauty parlor she owned and operated. This picture was the vehicle that allowed him to finally feel and express the depth of his grief. In a recent conversation with French gallerist Thierry Bigaignon—whose gallery is currently showing an exhibition of Gibson’s photographs—Gibson explained that when his mother died, he’d been so stunned that he could not cry. “The moment after I took the photograph,” he said, “I burst into tears.”

The Black Trilogy, a recent reissue of Gibson’s early self-published books, brings together The Somnambulist (1970), Déjà-Vu (1973), and Days at Sea (1974) in one volume. By making available books that had, over the years, become hard to find, the trilogy offers an occasion to reexamine Gibson’s singular career.

Born in 1939, by age twenty-seven Gibson had, like Richard Avedon, gone through an apprenticeship at the US Naval Photography School, as well as stints working as an assistant to Dorothea Lange and Robert Frank. He also worked briefly with Magnum Photos, shooting assignments for the agency. He quickly realized, however, that he did not want to be a photojournalist: he had no interest in capturing “events.” He wanted photographs that would last, that expressed his innermost emotions and were worthy of contemplation. Rather than adopting what he saw as the aggressive attitude of a photojournalist, he opted for a still, attentive stance akin to meditation, letting appearances engulf him: “I am not the music; I’m the radio through which the music plays. So I follow the work, I don’t lead the work. I go where the work sends me.”

Like a child who creates a medieval castle from a cardboard box, Gibson uses humble, everyday subjects—a pen, a shoe, a glass, a spoon, a mirror, a chair—to create dramatic and cinematic scenes. Gibson’s father was an assistant director to Alfred Hitchcock, and Gibson used to bike to the Hollywood studios, where he was an occasional extra. Surrounded by 1940s film stars like Grace Kelly and Rita Hayworth, he developed an admiration for the female form.

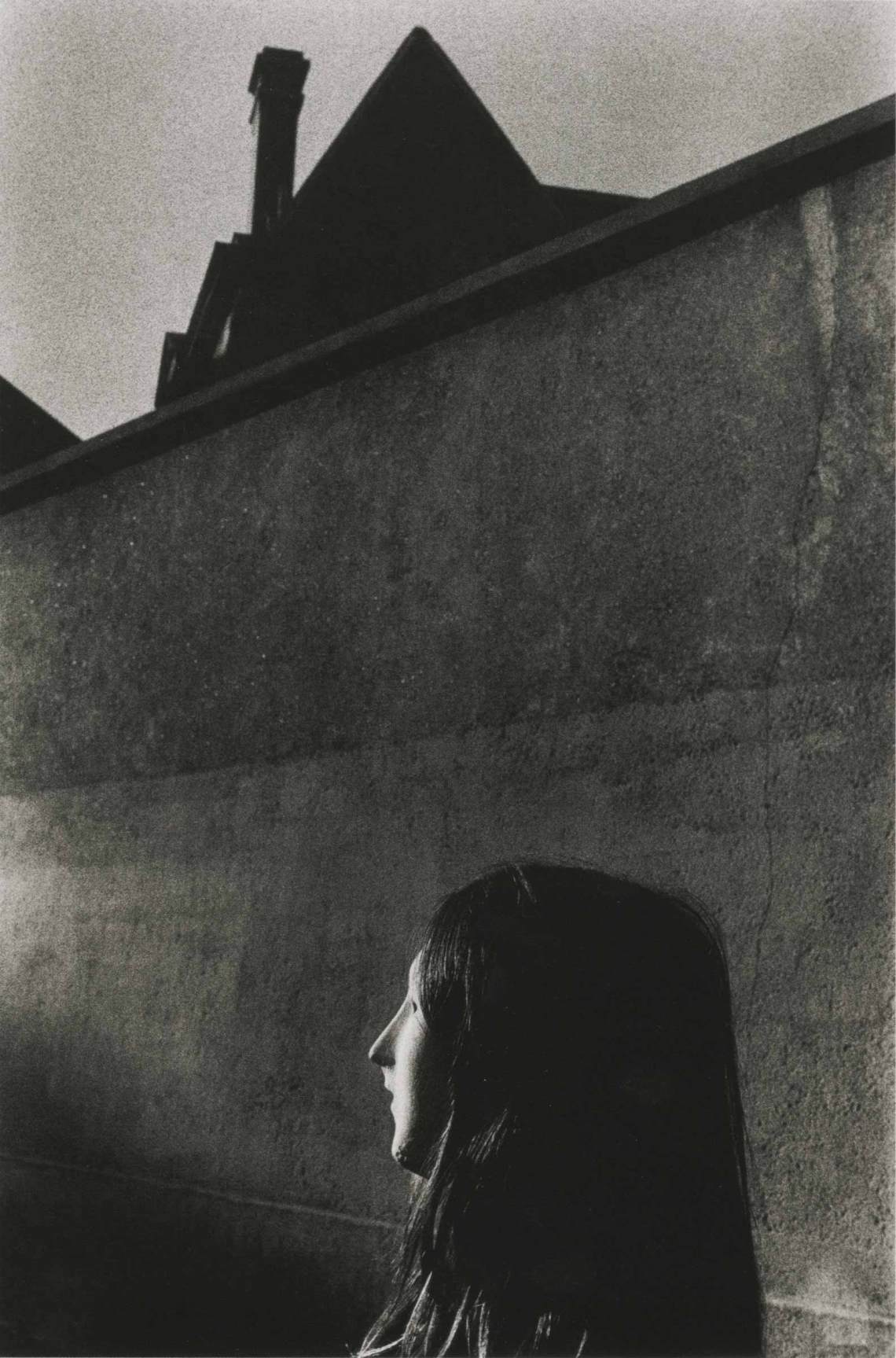

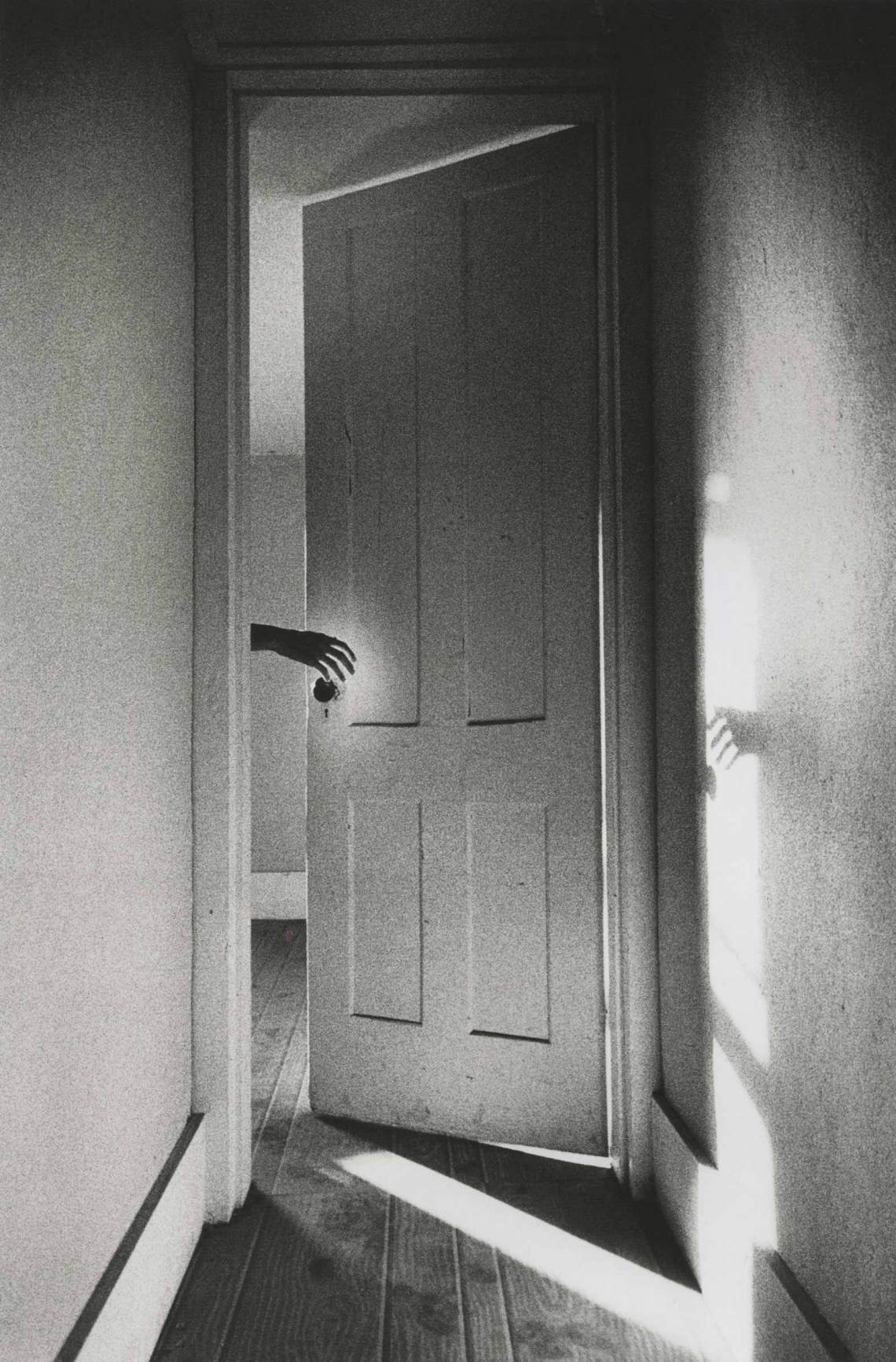

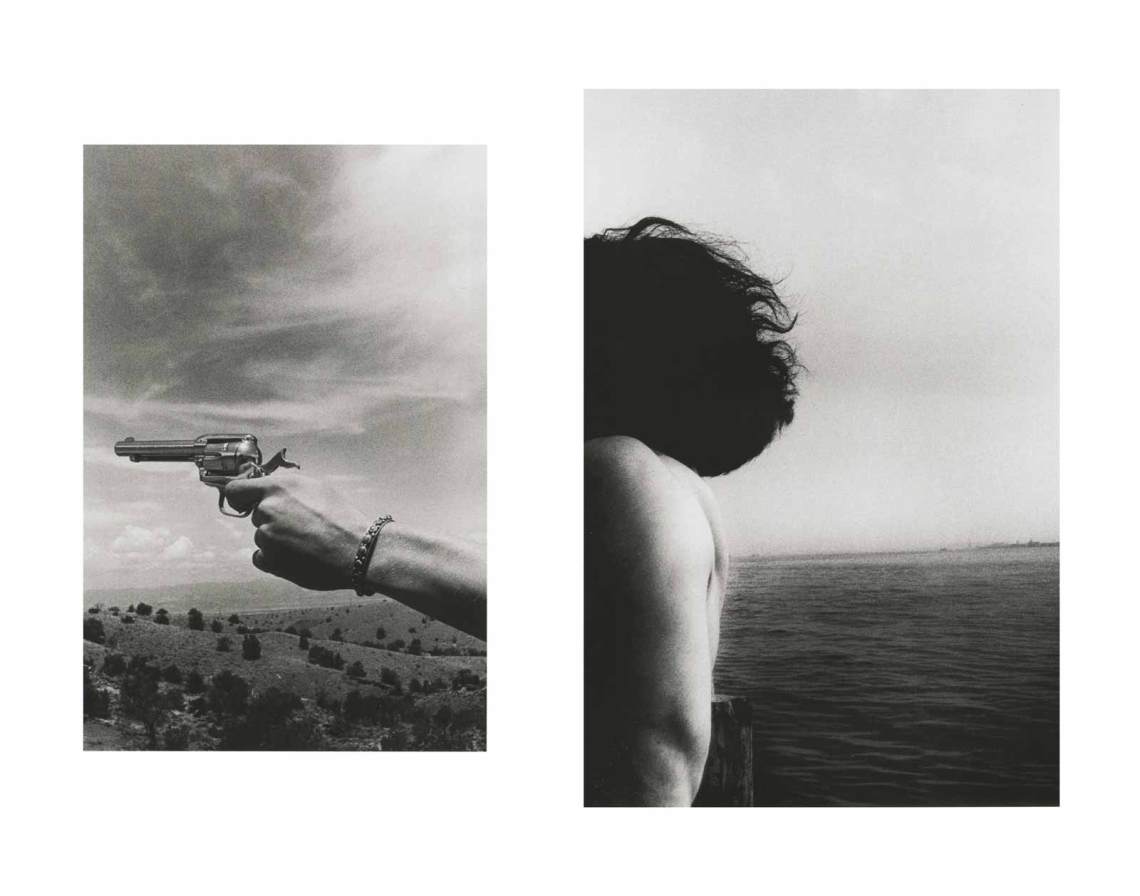

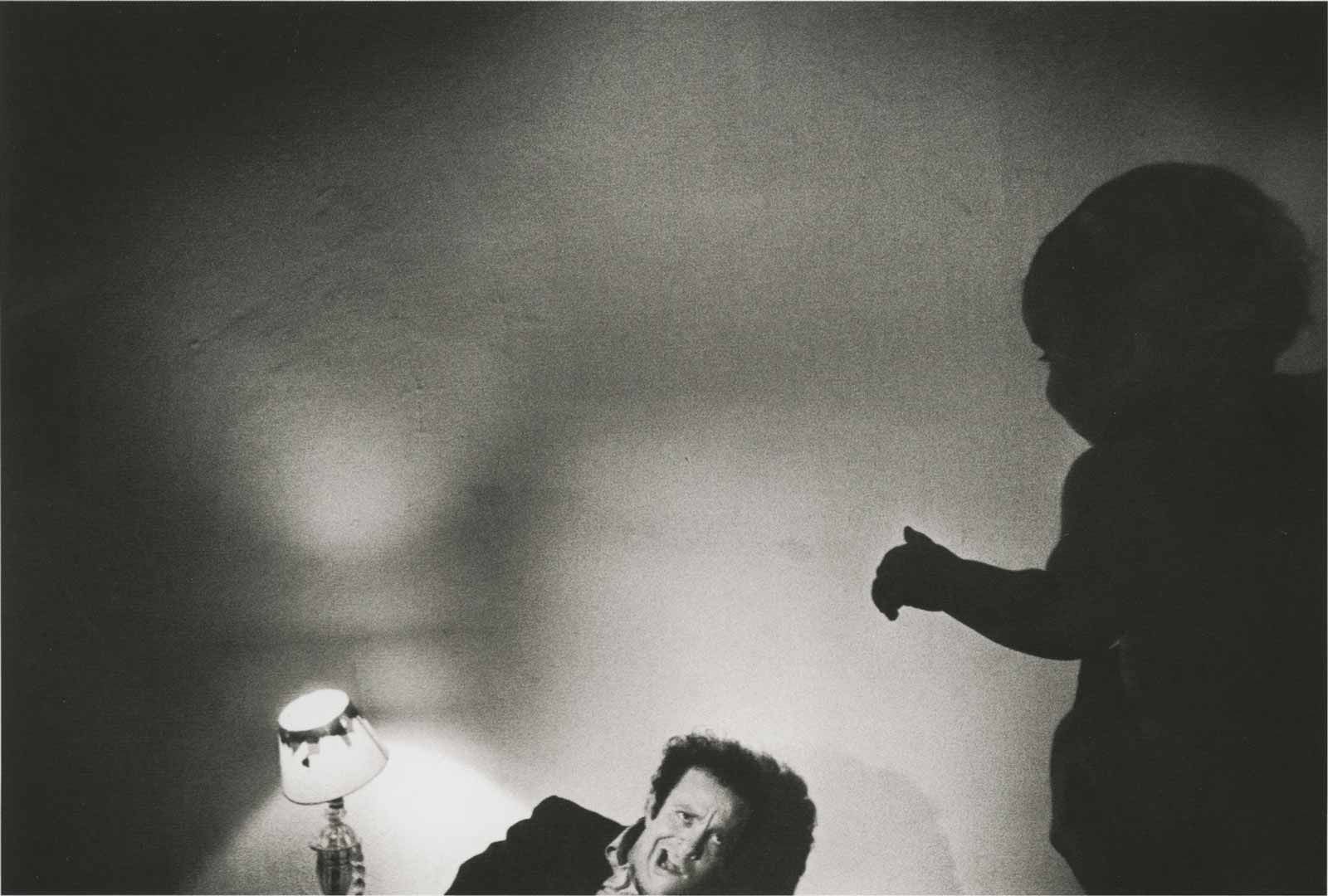

Gibson was also fascinated by the tight frames of Hollywood film stills. Long before he became aware of the work of Alain Resnais and Jean-Luc Godard, he acknowledged the influence of Orson Welles’s chiaroscuro and his deep-focus cinematography, in which all the elements in the image are sharply detailed, and where the frame, incorporating low-angle shots, is dominated by clearly defined shadows that create a sense of mystery and suspense through concealment. Gibson’s images, with their mysterious visual clues, often evoke a crime film or film noir.

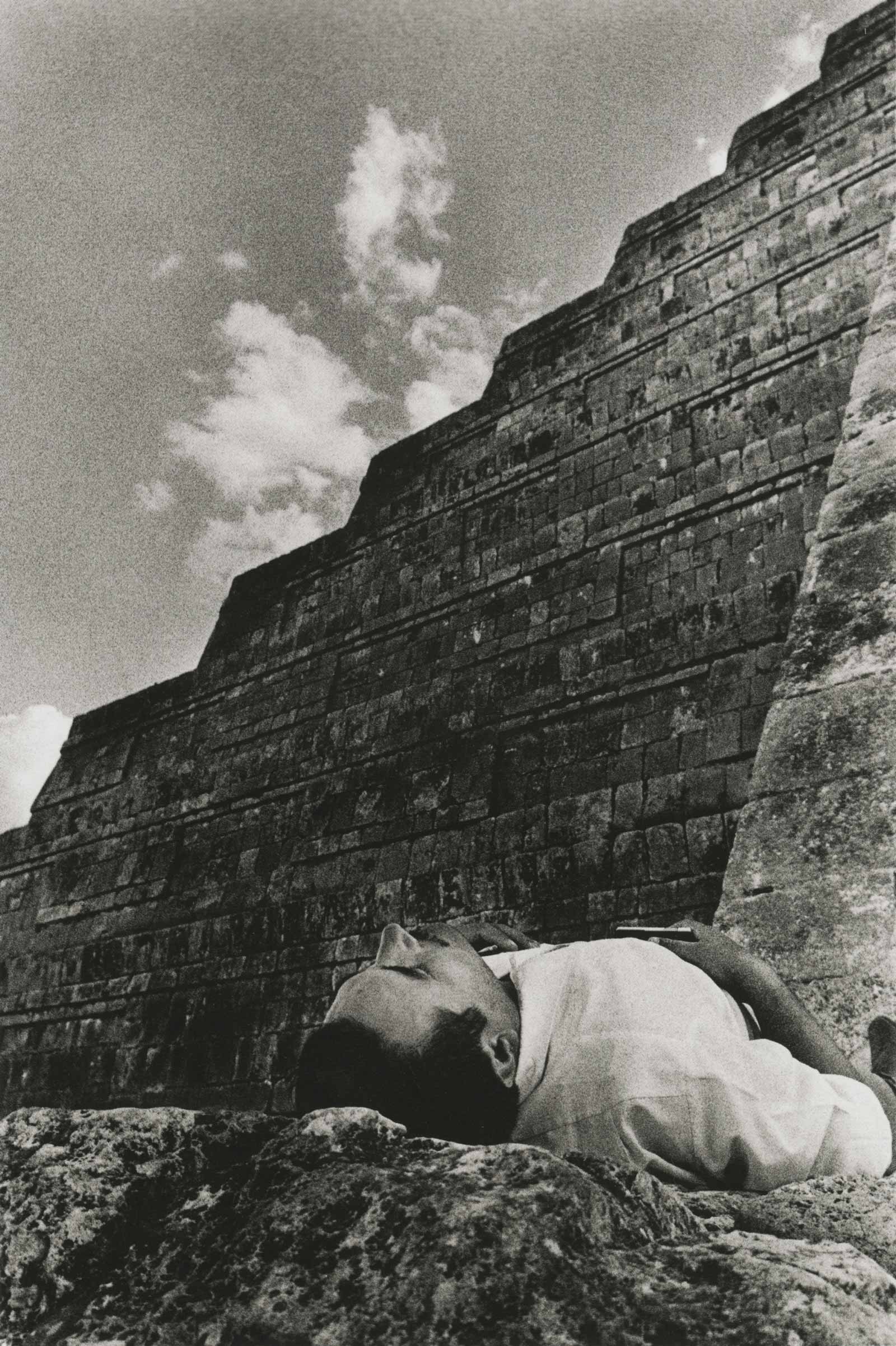

Literature has also been a major inspiration for Gibson. The concise yet detailed styles of two of his favorite writers, Jorge Luis Borges and Marguerite Duras, influenced his photography. For instance, a photograph from Déjà-Vu, probably a self-portrait, features a man sleeping at the foot of an Aztec pyramid, like the priest-hero of Borges’s story “The Writing of the God.” As in another Borges story, “The Garden of Forking Paths”—where the center of the labyrinth is never discovered, only more paths uncovered—the more time one spends in Gibson’s hypnotic images, the more lost one becomes.

In 1970, after The Somnambulist had been rejected by several publishers, the thirty-year-old Gibson took a risk: already nine months late with his rent at the Chelsea Hotel, his Leica in hock, he went $4,000 further into debt to produce The Somnambulist and start his own imprint, Lustrum Press. It would be followed by two more of his own books, Déjà-Vu (1973) and Days at Sea (1974). He was moving away from the sort of work showcased by John Szarkowski’s landmark 1967 MoMA exhibition “New Documents”—which focused on new, at times sardonic, documentary photography from Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, and Garry Winogrand. Along with William Klein, Robert Frank, and others, Gibson is credited with reimagining the modern photo book, transforming it from its more illustrative, thematic approach to a deeply personal, artistic form where the sequence is based on free association rather than chronology or narrative.

Advertisement

His own images exist in a suspended, frozen time and space; they are more allegorical than illustrative, visionary rather than simply visual. Music permeates Gibson’s bookmaking, where the stream-of-consciousness sequences entail subtle echoes, riffs, leitmotivs, and, above all, the sound of silence in the ample spaces left to white. A gifted guitarist, in 1974 he made the album New Skin for the Old Ceremony with Leonard Cohen.

Lustrum also published celebrated monographs dedicated to then little-known artists Larry Clark (Tulsa, 1971), Robert Frank (Lines of My Hand, 1972), Danny Seymour (A Loud Song, 1972), Mary Ellen Mark (Passport, 1974), Duane Michals (Sleep and Dream, 1984), as well as thematic books that brought together a wide array of photographers. Nude: Theory (1979), for instance, contains photographs and essays by Manuel Alvarez Bravo, Harry Callahan, Lucien Clergue, Kenneth Josephson, Andre Kertész, Duane Michals, Helmut Newton, and Gibson himself.

“It was very strange,” Gibson has said, recalling the moment his books began to gain interest, before he’d ever exhibited his work. “I went from an impoverished nobody to all of a sudden being on my feet. I was getting a lot of press, doing lectures and workshops, and selling the occasional print.”

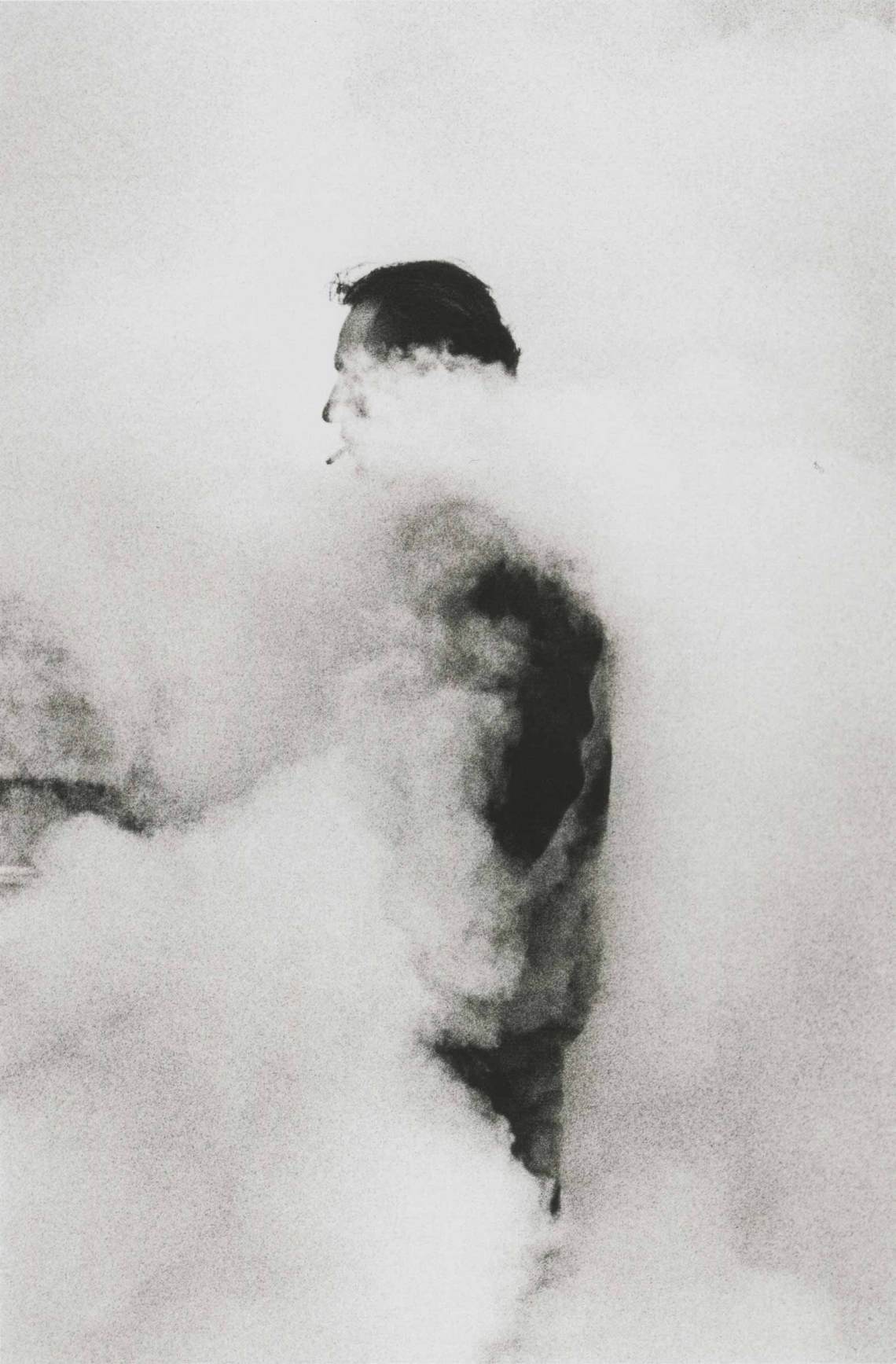

Except for his portraits of fellow artists Mary Frank and Mary Ellen Mark, people in The Somnambulist are mostly seen from the back or with their features partially obscured. Faces become more prominent in Déjà-Vu, and in Days at Sea, the female body reigns supreme. In all three books, shadows become shapes, taking on lives of their own, playing as great a part as the figures themselves. In an image from The Somnambulist, a man’s face, with a terrified expression, is relegated to the bottom of the frame while the gigantic, dense shadow of a small child towers menacingly over him.

Though The Black Trilogy offers a new generation of viewers exposure to Gibson’s pioneering works, I can’t help having mixed feelings about the new publication. Is it because of the format—taller than the original books? The stiff covers? Or simply because this is a thicker volume, and some of the sense of preciousness and intimacy of the original Lustrum editions has been lost? The Black Trilogy feels more like a catalog than a book, a collation rather than a revelation, and Ralph Gibson’s intrepid photographs may have lost some of their magic in the process.

The Black Trilogy, with text by Gilles Mora, is published by Editions Hazan in Paris and the University of Texas Press. “Vu, Imprévu,” an exhibition of Ralph Gibson’s photographs, is on view at the Galerie Thierry Bigaignon in Paris through May 12.