In 2012, an interviewer asked the French filmmaker Claire Denis about the genesis of her 1999 movie Beau Travail—a fevered vision of jealousy and desire loosely adapted from Herman Melville’s “Billy Budd” and set in Djibouti amid an all-male troop of French legionnaires. She had been reading a poem of Melville’s called “The Night March,” she answered.

It’s a lost battalion of soldiers, lost in the night without their commandant or captain or whatever, without a commander…They don’t know where they’re going. The only thing they can see is the moon reflecting on the metallic pieces of their guns.

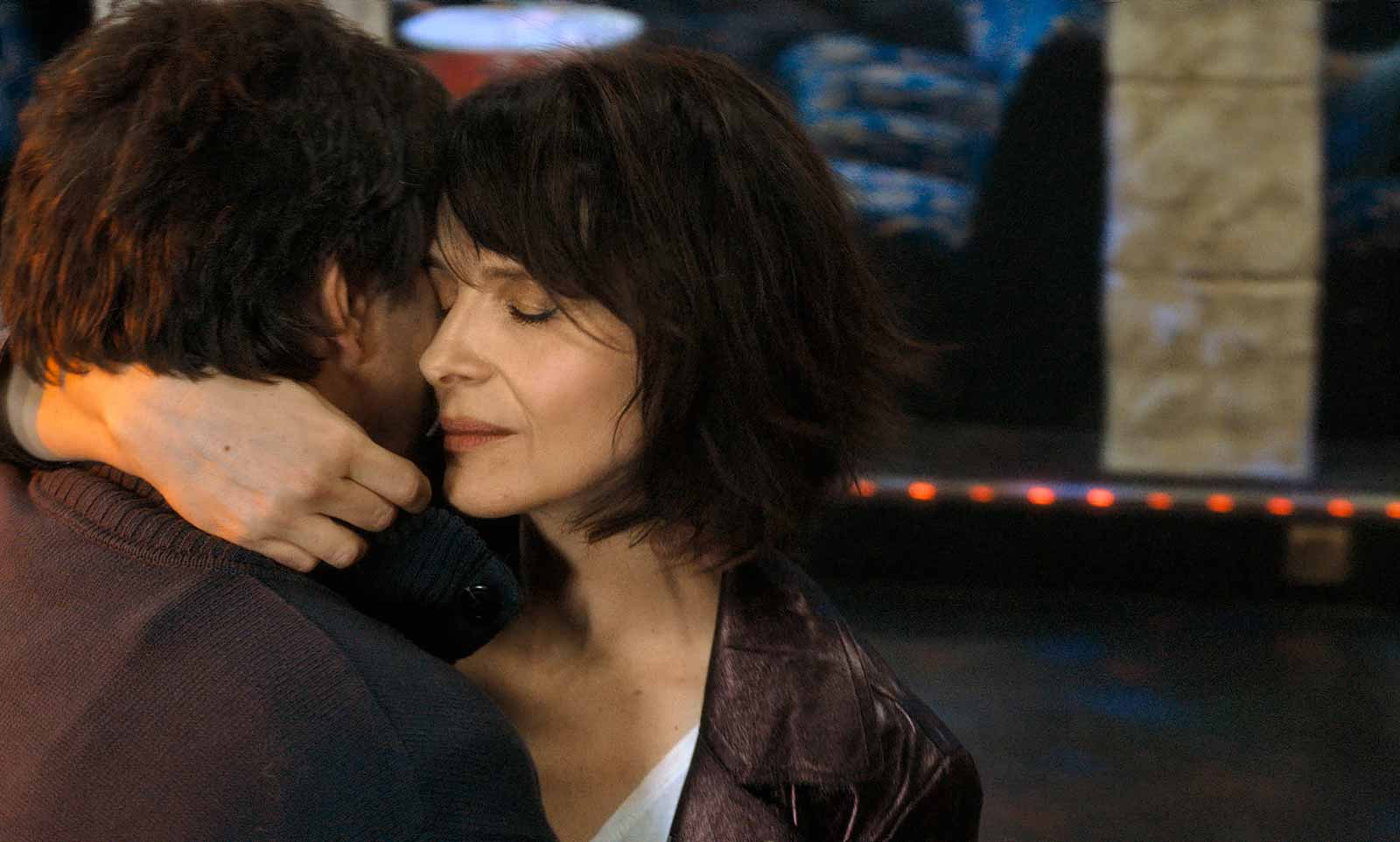

It was an answer that said as much about Denis’s films as it did about the brief poem that inspired it. Her thirteen narrative features suggest how many ways it is possible, as a filmmaker, to dislocate your characters from comfort and clarity and strand them in dark places where they can’t find their way. Only in Beau Travail did this dislocation involve a military group like the one Melville evoked. Her other films center on immigrants of color in Paris, white Europeans in Africa, men who desire one another in secret, and women like Isabelle (Juliette Binoche), the divorced middle-aged painter at the center of Denis’s new film Un beau soleil intérieur (retitled Let the Sunshine In for the US), who spends the movie looking for a passionate, enduring love.

Desire is both a source of momentum for these characters and a wellspring of confusion and instability. “There’s a chemical reaction between men and women,” says a baker’s wife to the young man who lusts after her in Nénette et Boni (1996), and the people in Denis’s movies often seem linked by invisible channels of longing. They smell one another, admire one another from afar, dance around one another, and in the process lose their footing in the worlds they occupy. To want to get close to another person, for Denis, is to venture into strange and unknown territory.

For much of Denis’s early career, her films could be counted on for sustained visual pleasure. They were enveloping, sensuous creations no matter what lost or frustrated lives they showed. When she chooses, Denis can still make movies of lush beauty, like her 2008 family drama 35 Shots of Rum; but her recent output has tended to be pricklier, more abrasive, and less immediate in its rewards. Un beau soleil intérieur—in which Binoche’s character negotiates her relationships with five men over an indeterminate number of months—is both Denis’s most overtly comic film and one of her least predictable in tone. It suggests the extent of her willingness to commit to the logic of a character’s alienation and risk whatever frustrations and surprises it brings.

*

Denis was born in Paris in 1946. Almost immediately after her birth her parents re-located to Africa, where her father eventually started working as a colonial administrator; he nonetheless supported the national independence movements that swept the continent during his daughter’s childhood. She grew up in Cameroon, Somalia, Djibouti, and Burkina Faso. The family moved every two years, she told one interviewer, because her father “couldn’t stand our not knowing about geography.”

For a decade starting in the mid-1970s, she worked as an assistant to film directors, including Wim Wenders, Jim Jarmusch, and the Serbian provocateur Dušan Makavejev, who once instructed her to spend a night with a radical Viennese anarchist collective that specialized in extreme, scatological performance art. “I wasn’t afraid because I was unreachable,” she later said, “not because I am a pretentious person but because I have a dreamy distance with reality, which is not a really good thing.”

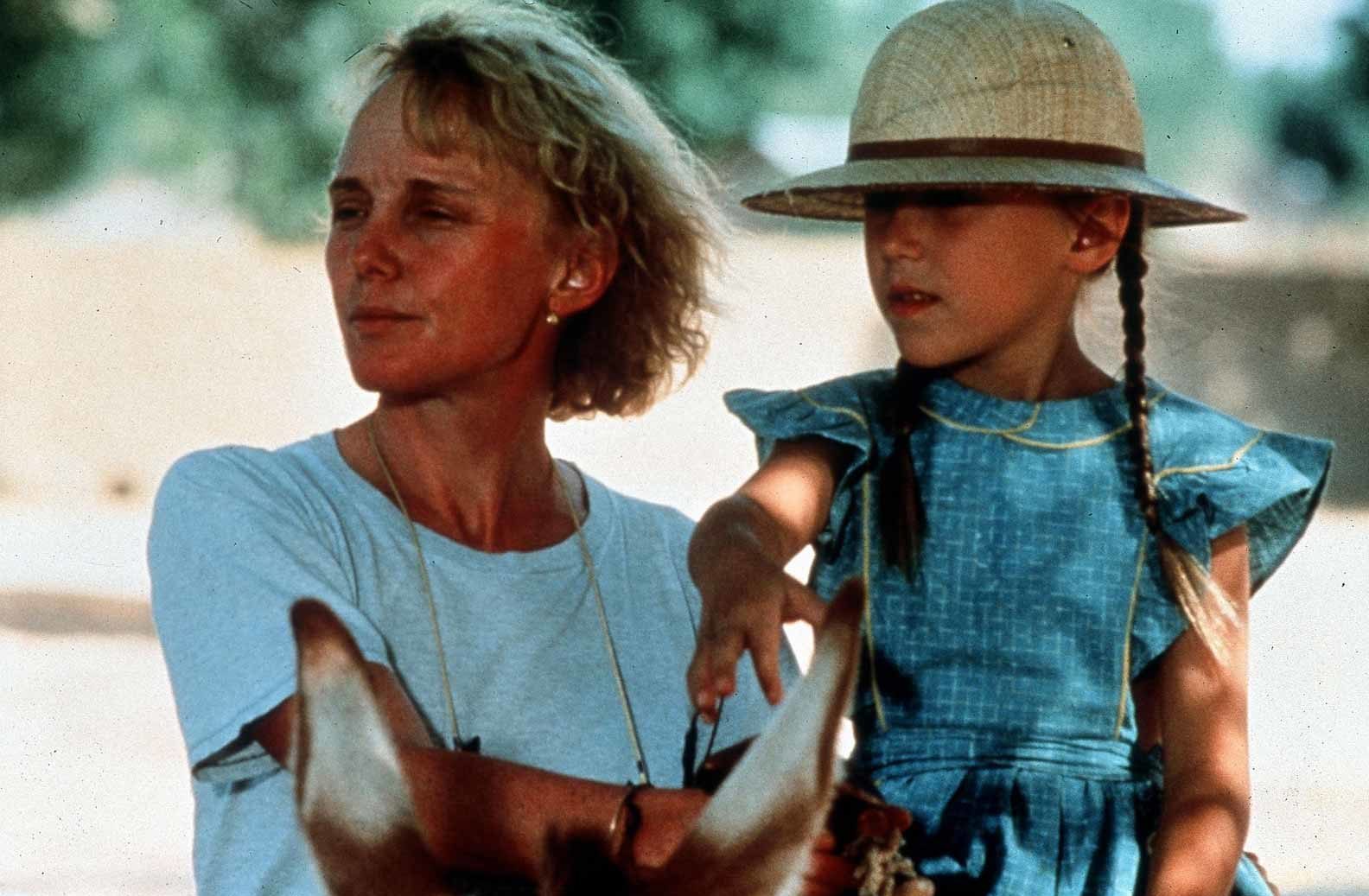

Denis’s childhood in Africa became the basis for her first feature, Chocolat (1988), which dwelled on the tensions among a white administrator’s wife in colonial Cameroon, her young daughter, and their black manservant (played with formidable quietude by the Ivorian actor Isaac de Bankolé). After a pair of documentaries, on the Cameroonian dance band Les Têtes Brulées and the filmmaker Jacques Rivette, there followed one of the most startling runs of inspiration in contemporary cinema. Over her next five films, Denis introduced us to a series of indelibly lonely characters: the two immigrant friends—one Beninese, the other West Indian—who join a cockfighting ring in No Fear, No Die (1990); the young Parisian man from Martinique who kills old women by day and puts on dreamy, enveloping drag shows by night in I Can’t Sleep (1994); the suburban teenage girl who ends up driving through a forest at night with an American GI in U.S. Go Home (1994); the combative siblings at the center of Nénette et Boni (1996); and the career legionnaire brought to ruin by his obsession with a younger recruit in Beau Travail.

Advertisement

By her second feature Denis had already moved away from the handsome, formal medium-shots that dominated Chocolat. Her collaboration with the cinematographer Agnès Godard—which began with I Can’t Sleep and has continued over ten films since—led her further into new stylistic terrain. Under their direction, the camera tends to stay close to its subjects rather than establish spatial continuity across cuts or place actors relative to one another; wider shots like the ones in Chocolat are held in reserve to punctuate long strings of tight, intimate images. Denis treats the people in her movies as free-floating bodies, concentrating on their shoulders, upper arms, or earlobes, cutting to close-ups of their faces in intense moments of feeling or thought. In some scenes, her camera seems supremely self-possessed, dancing around its subjects with grace and ease. In others, it moves with nervy hyper-assurance or vulnerable disorientation. In still others, it mimes lust for the people it films and follows them closely enough to smell their perfume or sweat.

The camera moves, in other words, much as her characters do. The people in Denis’s films rarely have much to say. Instead, they cultivate intense physical presences and communicate by gesture, movement, and eye contact. The five narrative films Denis made in the 1990s all turn on dance scenes or moments of wordless communion set to pop songs: Jocelyn (Alex Descas) leaping around with his prize chicken to “Buffalo Soldier” in No Fear, No Die, for instance, or the wild, cathartic dance with which Denis Lavant’s disgraced officer lets loose at the end of Beau Travail. Similar scenes recur in Denis’s recent work. When Isabelle starts dancing on her own to Etta James’s “At Last” to seduce a handsome loner in Un beau soleil intérieur, it’s as if she’s undergoing a rite of passage that nearly all of Denis’s protagonists have had to face.

*

One of Denis’s few films to lack a dance scene was her most recent, Bastards (2013), an unrelentingly dreary transposition of William Faulkner’s Sanctuary to contemporary Paris. It’s startling to see her follow that film about political corruption, incest, and sexual abuse with what the critic Amy Taubin has not inaccurately called a “bedroom farce.” But this is not the first time Denis has used one movie to treat the wounds its predecessor left. In 2001, she made a graphic body-horror film called Trouble Every Day, in which a man and a woman afflicted with a mysterious drive to cannibalize their sexual partners feed on anonymous lovers to keep from devouring their spouses. (“It is how a kiss becomes a bite,” Denis said.) More disquieting than the movie’s unpleasant subject is the identification it forces between us and these predatory characters. The camera stalks one of their victims—a young chambermaid—at close range through a hotel hallway, lingering on the nape of her neck with something like its own hunger.

Denis followed that harrowing film with what remains her most tender, delicate, and mischievous work. Friday Night (2002) centered—like Un beau soleil intérieur—on a Parisian woman at a juncture in her romantic life. We meet Laure (Valérie Lemercier) as night falls on the city and leave her twelve hours later. It is through her eyes that we take in the many fleeting details that move the film along: the boxes she arranges in her bare apartment as she gets ready to move in with her boyfriend; the traffic jam in which she gets stuck during a mass transit strike; the handsome stranger (Vincent Lindon) to whom she offers a lift; the cigarettes he smokes; the condom machine he uses when they stop at a late-night coffee shop; the trappings of the motel room she rents with him; the movements of his body as he discards his jacket and shirt.

We never meet the boyfriend she’ll presumably rejoin after her one-night stand, and as the film goes on he hardly seems to matter. What counts is the texture of Laure’s disorientation as she gives herself up to an unexpected adventure and savors its rarity and strangeness. Nearly all of Denis’s films before Friday Night concluded with a scene of death or defeat. This one ends on a slow-motion vision of its heroine smiling enigmatically and sprinting through the streets of Paris at dawn.

Advertisement

*

The first shot of Un beau soleil intérieur warns us not to expect similar comforts here. For about fifteen seconds, the camera—again under Godard’s supervision—cranes directly over Isabelle’s prone body as she lies sprawled on a bed. We’ve begun the film, we realize, not from her line of sight but from that of the grizzled banker we see looming over her a moment later. The clumsy, unsatisfying sex scene that follows between them could hardly be further from the extended, luxurious lovemaking passages in the second half of Friday Night. She gets tired of his graceless performance and tells him to finish. When he picks up on the impatience in her voice, he goads her into slapping him and leaves her sitting in tears, after which Denis takes us to a brief scene of Isabelle lying in bed alone, watching her curtains glow in the sun.

Over the course of the film Isabelle will fend off this crass figure’s subsequent advances, fall in and out with her ex-husband, and get involved with three more, mercurial men: a sleazy, alcoholic actor fed up with his marriage (Nicolas Duvauchelle), a quiet loner named Sylvain (Paul Blain) whom she meets in a small-town bar, and a handsome, shy member of her art-world circle listed in the movie’s credits only as “the thin man” (Descas, in his ninth performance for Denis). How much time the movie covers is up for speculation. “Let’s not worry about knowing if a scene took place yesterday, the day before that, or last year,” Denis said she told Angot as they wrote. “There are thirty-four blocks in the life of this woman… Who knows how much time separates them?” A cut might signal the end of a relationship (as it does with Sylvain) or the start of a possible new one (as it does with Descas’s character). On the other hand, it might signify nothing more than a change of scene. Little could be farther from the compressed, one-night timeframe within which Friday Night played out.

Watching Un beau soleil intérieur, you can feel Denis testing how many elements in a movie—tone, structure, timeline, roster of characters—can be left unstable in the service of capturing a single person’s estrangement. Only once does this bedroom farce return to an actual sex scene: a foreshortened encounter between Isabelle and her former husband that ends when one of his seduction moves—teasingly sucking his finger—repels her. (“It’s like you’re copying something you saw,” she tells him.) What interests Denis is not sex itself, but how Isabelle and her fellow Parisians navigate around sex in the movements of their bodies and the words they deploy.

The words deployed in Un beau soleil intérieur might seem to matter more than the sparse and often incidental dialogue that filled Denis’s earlier films. There are certainly more of them. This is Denis’s second collaboration with Angot, after a short film from 2014 called Voilà l’enchaînement, and the script they wrote together turns on long verbal confrontations between Isabelle and her lovers. Denis and Godard adapt to these talky passages with a grace they rarely brought to scenes like the stilted expository dialogues in Trouble Every Day. They inhabit them so well, calling such attention to the actors’ gestures and physical presences, that you wonder if the words themselves are the point.

For all we hear Isabelle say, only a stray remark of Duvauchelle’s well into the movie reveals that she has a young daughter, who appears once onscreen through a car window. Much else about Isabelle’s life and career goes unreported or unexplored. Instead, as in Denis’s previous films, we get acquainted with her through sheer physical proximity over time. She can be sympathetic and exasperating, righteous and snobbish. She flies into a righteous rage at the conceited art-world men with whom she takes a weekend country trip; she also takes to heart her friend’s blithe, elitist dismissal of the working-class man she’s soon after involved with. Were we to encounter her in a different film, she might not be entirely likeable. But Denis and Binoche commit so wholeheartedly to tracking the movements of Isabelle’s consciousness that we hardly ever ask ourselves how fond of her we are. Her desires give the film its energy and rhythm; she’s rarely offscreen and we miss her the moment she is.

*

It is difficult to think of a character in Denis’s previous work who sets her sights on a kind of happiness so enduring and deep. Most of her protagonists chase transitory encounters, fleeting connections, and brief reprieves from the loneliness that is their steady lot. The caring, almost wordless one-night stand in Friday Night was the sort of blissful encounter that most of them aspire to. Isabelle has no patience for such short comforts. She wants not just a body for the night but a partner, a soulmate, a spouse. She would have asked more of Vincent Lindon’s stranger in Friday Night than that film’s heroine did; in a movie like this, his silence and reserve might have been frustrations rather than charms.

Because Isabelle demands more out of the unsatisfactory men who surround her, she also requires new commitments from Denis: a worldlier, more urbane attitude toward love and sex; a sharp eye for male pretension; a tolerance of long scenes in which people talk to get acquainted. Above all, she requires a new tone, one with a discomfiting mixture of whimsy and sourness. In Un beau soleil intérieur a joke might be followed by a moment of joy (like the one Isabelle basks in after her first evening with Duvauchelle’s character), only for the atmosphere to sharply turn ugly or bitter. One brief scene shows Isabelle taking the Metro back from lunch with a female friend and muttering to herself about the woman’s self-satisfied account of her settled love life.

Previous Denis protagonists did not generally have mood swings. They stayed immersed in deep reservoirs of longing and solitude—of which an extreme case was the reclusive ex-mercenary that Michel Subor played in The Intruder (2004)—or slowly worked themselves up to some great act of violent release. Few of them ever seemed, as Binoche does in her extraordinary performance here, to be carrying themselves up and down on waves of energetic hope and bitter disappointment. But none of them wanted quite so much.

From time to time, Denis has asked us to consider the possibility that the remarkable sensitivity she gives her characters is precisely what leaves them lost and estranged. They react to other bodies too intensely, as Lavant’s doomed officer does to Grégoire Colin’s handsome young recruit in Beau Travail, or as the urban cannibals in Trouble Every Day do to the people they desire. Denis’s films often turn on scenes that call into question the way of seeing they themselves encourage. Is it healthy, they ask, to cultivate the feverish attentiveness these characters keep up?

Un beau soleil intérieur ends with another of these scenes. Isabelle visits a fortune-teller (Gérard Depardieu), who assures her that she’ll find love if she keeps herself “open.” She repeats the word to herself and seems to wonder if it’s such good advice. Openness to the men who swirl around her has thus far made her restless and miserable. The same could be said of the extreme receptiveness to light, sound, and touch that Subor’s mercenary cultivates in his wooded home in The Intruder, or of the second sense that Descas’s divorced train driver develops for his adult daughter’s feelings in 35 Shots of Rum. Being “open” has rarely done Denis’s characters much good. That they don’t want—or know how—to live otherwise is the problem to which her movies keep returning. In 2004, when she mentioned her own “dreamy distance with reality,” her interviewer told her that he thought it was a good quality for making films. “But for life it is not,” she insisted.

Let the Sunshine In opens today in the US, and is playing in select theaters.