There is a photograph of my late grandmother and me posing in profile, showing off our similar sloping noses. As a teenager, I was deeply self-conscious of my nose. But in the company of my grandmother, whose daring style and self-possession I admired, I sensed that I might, one day, view it as an asset. I looked to images of my grandmother as a young adult—slim, with long legs and a coy smile—as a totem of hope for my future self.

In the exhibition “Selves and Others: Gifts to the Collection from Carla Emil and Rich Silverstein,” on view now at San Francisco’s Museum of Modern Art, there is a self-portrait of Sophie Calle called The Plastic Surgery (2000), in which a close-up photograph of the artist’s face is supplemented with text that begins, “When I was fourteen, my grandparents suggested that I needed plastic surgery.” The image is neatly cropped, just below her eyebrows and above her neck, magnifying the artist’s nose. Calle’s family, like my own, is Jewish. Raised in postwar Paris, steeped in a culture marked by anti-Semitism, her family was evidently less accepting of stereotypically Jewish features than my own, American family was.

Drawn from gifts to the museum from Emil and Silverstein, “Selves and Others” presents a varied if fragmentary account of 150 years of photographic history. Portraits of family members, lovers, co-conspirators, idols, and dear friends are divided into four themes, such as “Psychology and Mood,” “Connecting with Strangers,” and “Masquerade.”

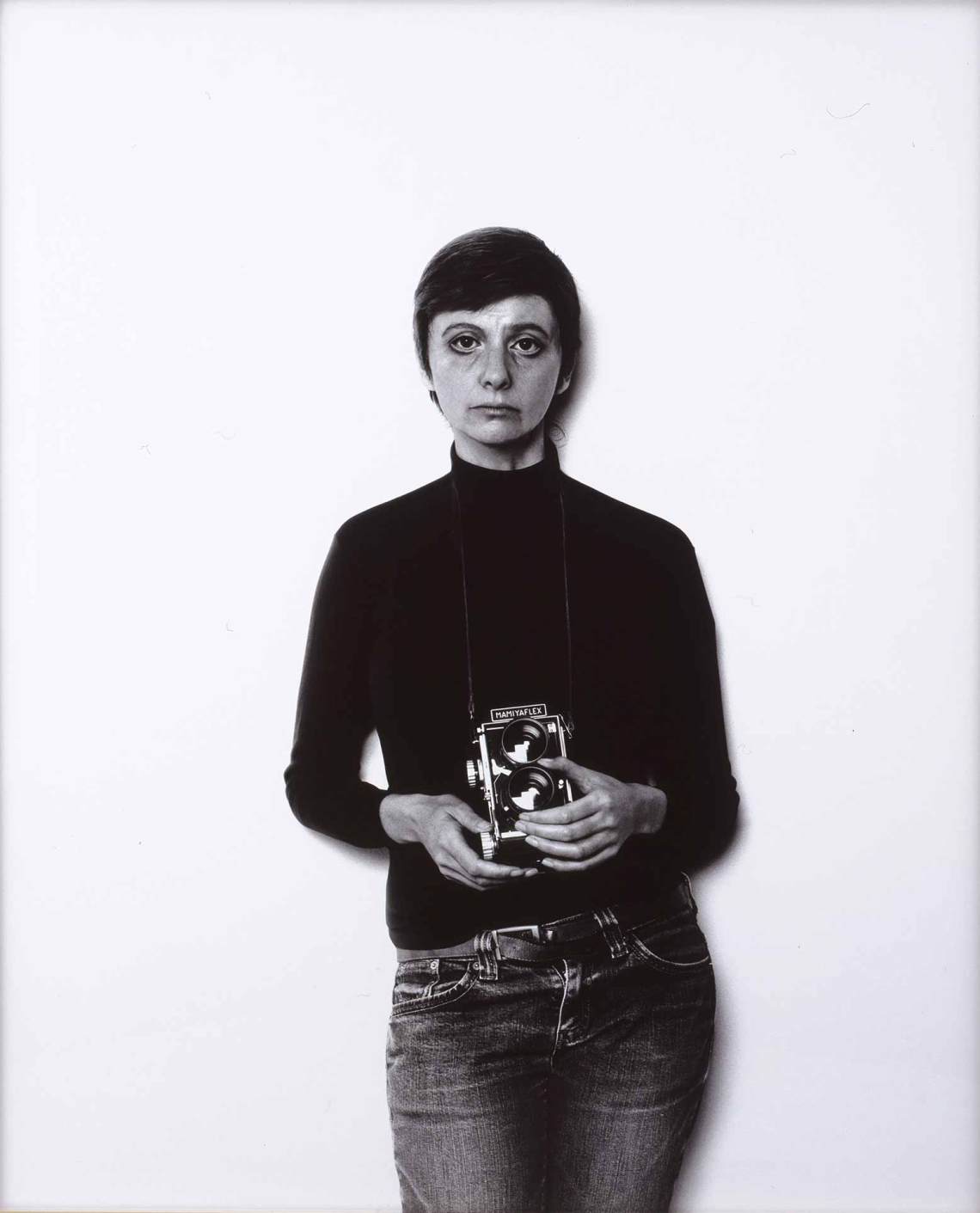

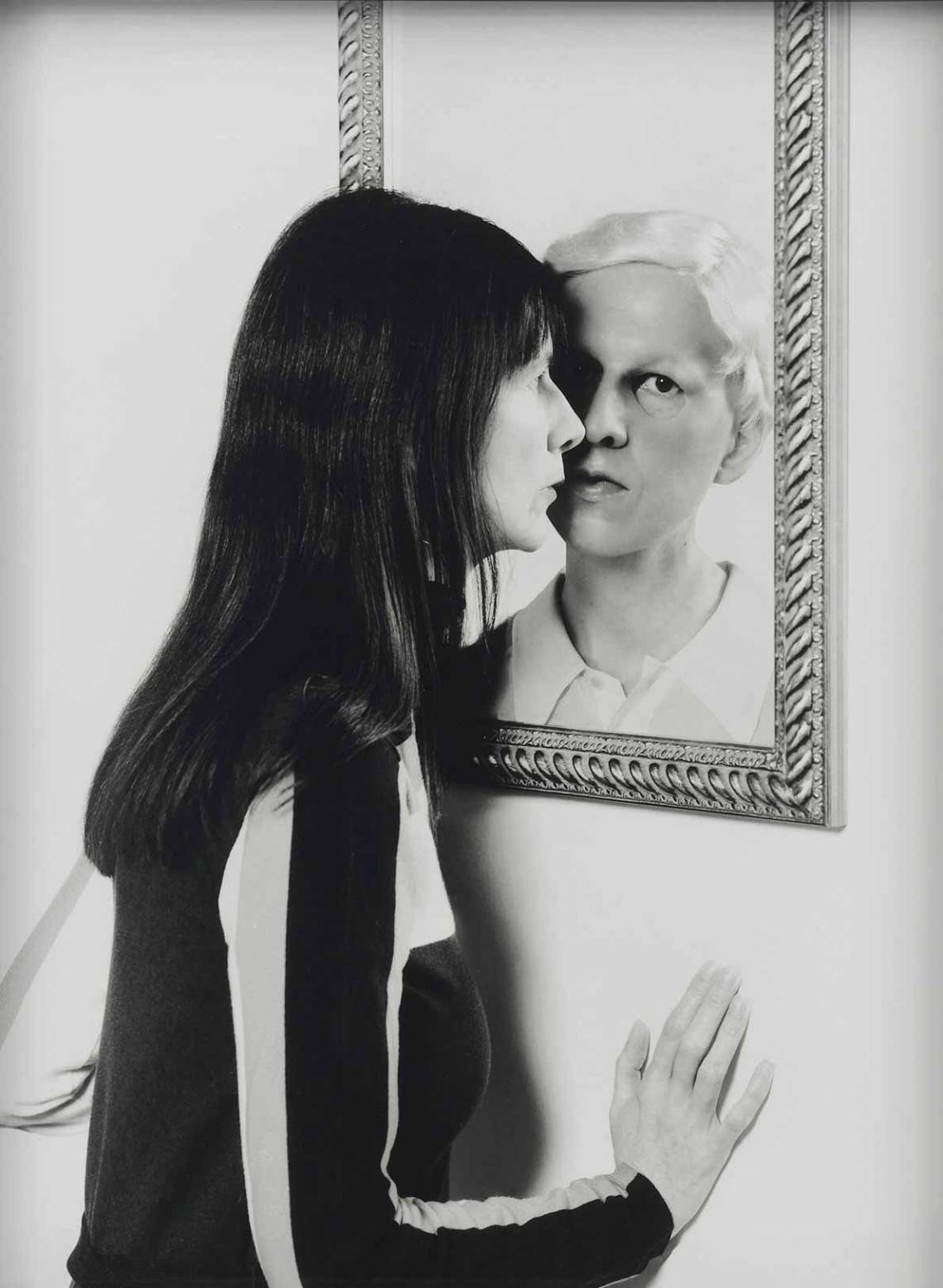

Well-known works by marquee portrait photographers—Cindy Sherman, Diane Arbus, and Lee Friedlander—dot the gallery walls, but it’s the British conceptual artist Gillian Wearing whose photographs demand viewers’ attention. (An enlarged version of Wearing’s Self Portrait as My Mother Jean Gregory (2003) is what visitors see upon entry to the exhibition.) In her “Family Portrait” series, Wearing uses custom silicone masks, era-specific wigs, and makeup to transform herself into her mother and father. In other works from the series, not included in this exhibition, she poses as her sister, grandmother, and seventeen-year-old self.

In Self Portrait as My Mother Jean Gregory, Wearing wears a prim blouse with pointed collars, her hair coiffed short. The artist is forty years old, but she poses quite convincingly as her mother at twenty-three. Giraffe-necked and with an upright, almost rigid posture, her direct, unflinching gaze is unnerving. If not for the subtle lines along her eye creases and jawline, it would be nearly impossible to detect that she is wearing a mask. The image effectively depicts two different people, subverting and expanding the sense of what a self-portrait can be. Though, technically, the photograph is of Wearing, the mask she wears conceals and obscures any distinguishable features; besides her eyes and neck, little of the artist’s physical self is actually visible. Throughout the series, Wearing’s identity is contingent on the identities of her parents, a material actualization of the way children inherit their parents’ behaviors. In the portrait of Wearing as her father, she becomes a formal, self-assured man; as her mother, she becomes a woman of another era, constrained by a particular set of familiar yet dated beauty standards. As Wearing embodies each of her family members, she becomes untethered to her own identity and instead takes on a sort of collective familial identity.

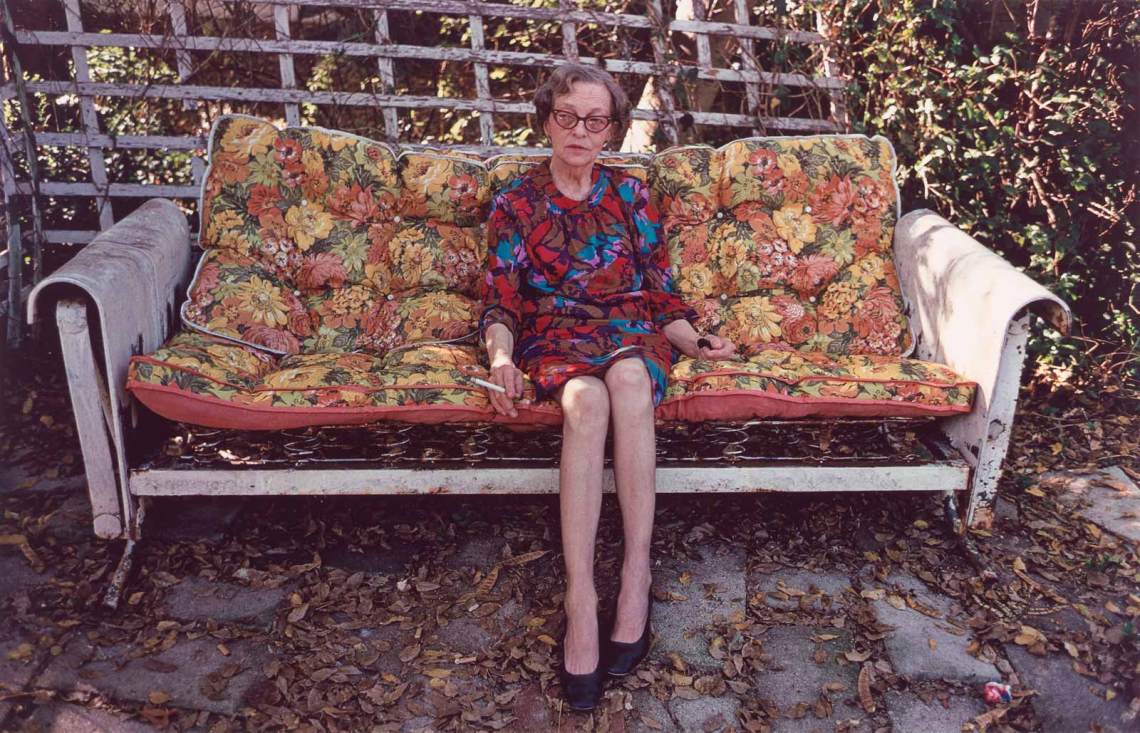

Cindy Sherman’s celebrated “Untitled Film Stills” (1977–1980) series is comprised of double-portraits as well, but it departs from Wearing’s series in its wide range of subjects. Whereas Wearing impersonates specific people she either knows intimately or admires from afar, Sherman poses as archetypal characters—the ingénue, the working girl, the bored housewife—that are reflective of culture more generally. As Sherman has said, “I am trying to make other people recognize something of themselves rather than me.”

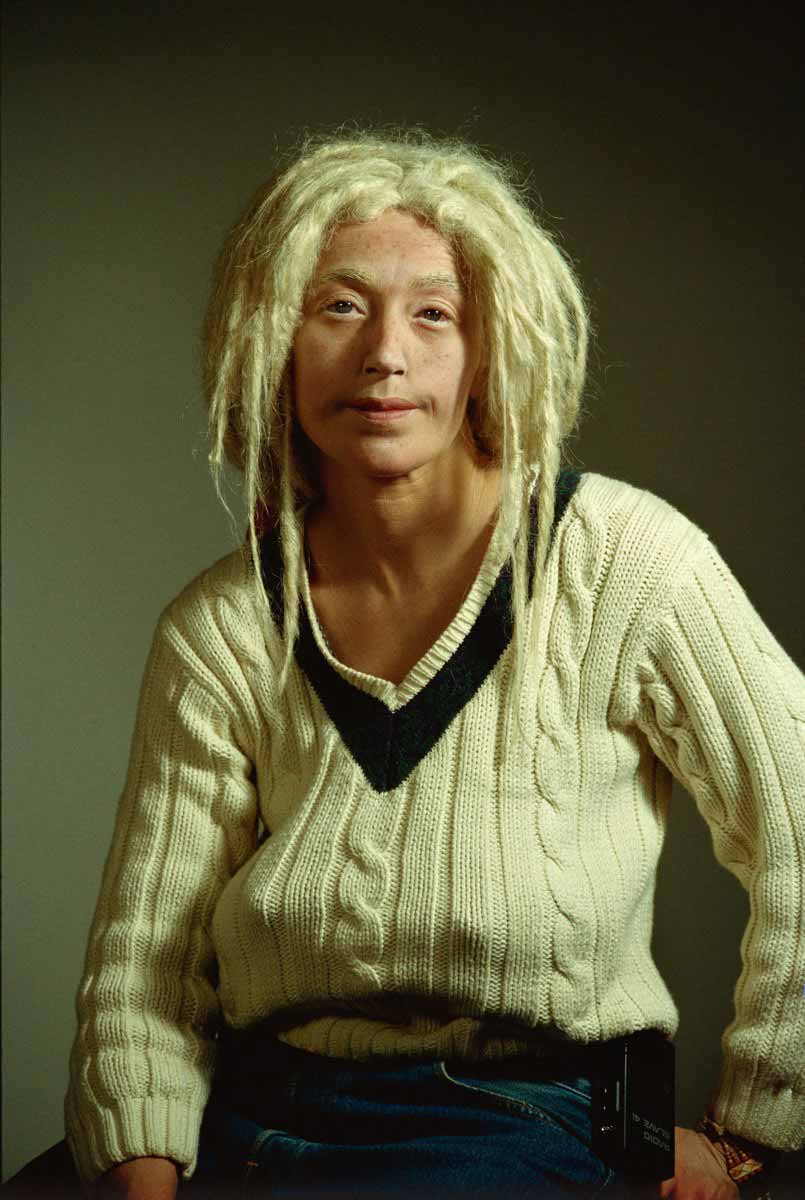

Posing as artists Diane Arbus and Claude Cahun, Wearing is able to explore another dimension of herself not found in the family portraits. As curator Erin O’Toole explained in an interview, “The lore of Arbus is something a lot of younger women artists of Wearing’s generation were attracted to.”

In Carrie Mae Weems’s Untitled, from The Kitchen Table Series (1990), the artist relaxes and leans toward a woman brushing her hair. Full wine glasses and cigarette packs strewn across the table contribute to the scene’s overall sense of warmth and intimacy. The relationship between the two women is vague: if they are not related, their position suggests that they must at least be close friends. In this scene, simple actions—grooming, drinking, smoking—signal that the subjects belong: in this room, near each other, and to themselves.

Advertisement

“Selves and Others” is at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art through September 23, 2018.