How do you open an art gallery of your own in New York City, where real estate costs defy gravity, and focus on emerging artists of color who don’t yet fetch the kinds of prices necessary to cover commercial rent—while also selling to people who don’t think of themselves as buyers or collectors of art?

It was a question that vexed curator and writer Stephanie Baptist in the four years after she returned home to the US from the UK, where she had been working as the inaugural head of exhibitions and public programs for Tiwani Contemporary, a London gallery specializing in artists from Africa and its diaspora. Baptist thought back to her work as a graduate student at Goldsmiths, where she had been interested in transforming unused spaces—from abandoned parking lots to city blocks directly under elevated subway tracks—as platforms for arts and culture in underserved communities.

In 2017, staring at the walls of her apartment on the top floor of a Crown Heights brownstone, she realized that her own living room held an answer. Last June, she moved the furniture out and held her first gallery opening, christening the five-hundred-square-foot space “Medium Tings”—“medium” as a play on both art materials and on the size of artwork that can fit in a living room, and “tings” to pay reverence to the Caribbean roots long planted in the Brooklyn neighborhood, one in the throes of gentrification and its fallout.

Medium Tings—and Baptist’s home—is on Eastern Parkway, like the nearby Brooklyn Museum of Art, around which a controversy ensued after the museum recently hired a white consulting curator for its African Art collection. The residents on Baptist’s block reflect the neighborhood’s demographics, with Caribbean Americans, observant Jews, and now white transplants, among others.

She chose for her opening show to feature the artist Jonathan Gardenhire, whose portfolio she had reviewed when he was still an undergraduate at Parsons in 2015. At a time when many Americans were talking about the policing of young black men, she saw Gardenhire’s deeply personal exploration of young black masculinity through photography as powerfully engaging the political moment. Gardenhire’s show was followed by the work of Lagos-based installation artist Temitayo Ogunbiyi and American photographer Arielle Bobb-Willis. Since it opened, Medium Tings has counted nearly six hundred visitors (the gallery is open only on Sundays or by appointment) and has sold work ranging from $125 to $5,000, to first-time buyers as well as art professionals. (Baptist advertises through her mailing list and social media.)

Baptist readily acknowledges that she’s hardly alone in working to support diversity by showing the work of artists of color, nor is she unique in trying to create exhibitions that draw audiences beyond the usual art-going crowd. “I’m part of an ecosystem of independent spaces that are pushing for more diverse narratives, and to provide platforms that allow artists the flexibility and freedom to explore and engage what they want,” says Baptist. Neither is she the only one to turn her home into a gallery—a tradition with a long history, increasingly common today, and embraced by practicing artists as well. In Brooklyn, other mixed residential-gallery spaces include an outpost of the well-established San Francisco gallery Jenkins Johnson, as well as Welancora and Fou—all multifloor homes.

Medium Tings notably offers the validation of a gallery show to artists who are mostly under thirty. Albeit in a living room, the shows are still curated, professionally exhibited (Baptist repaints her walls to best offset the works), and documented. The artists may have already shown work in coffee shops or in pop-up spaces, but at Medium Tings, their art is seen by larger audiences and collectors, often for the first time. New collectors are initiated at Medium Tings, as well. Several of the artists Baptist has shown, as well as those who have bought from the gallery, credit the intimacy of the living room itself, which allows people to visualize these works on their own walls after seeing them displayed in rooms not unlike their own. (Baptist has also just partnered with Art Money to allow buyers to pay with installment plans.)

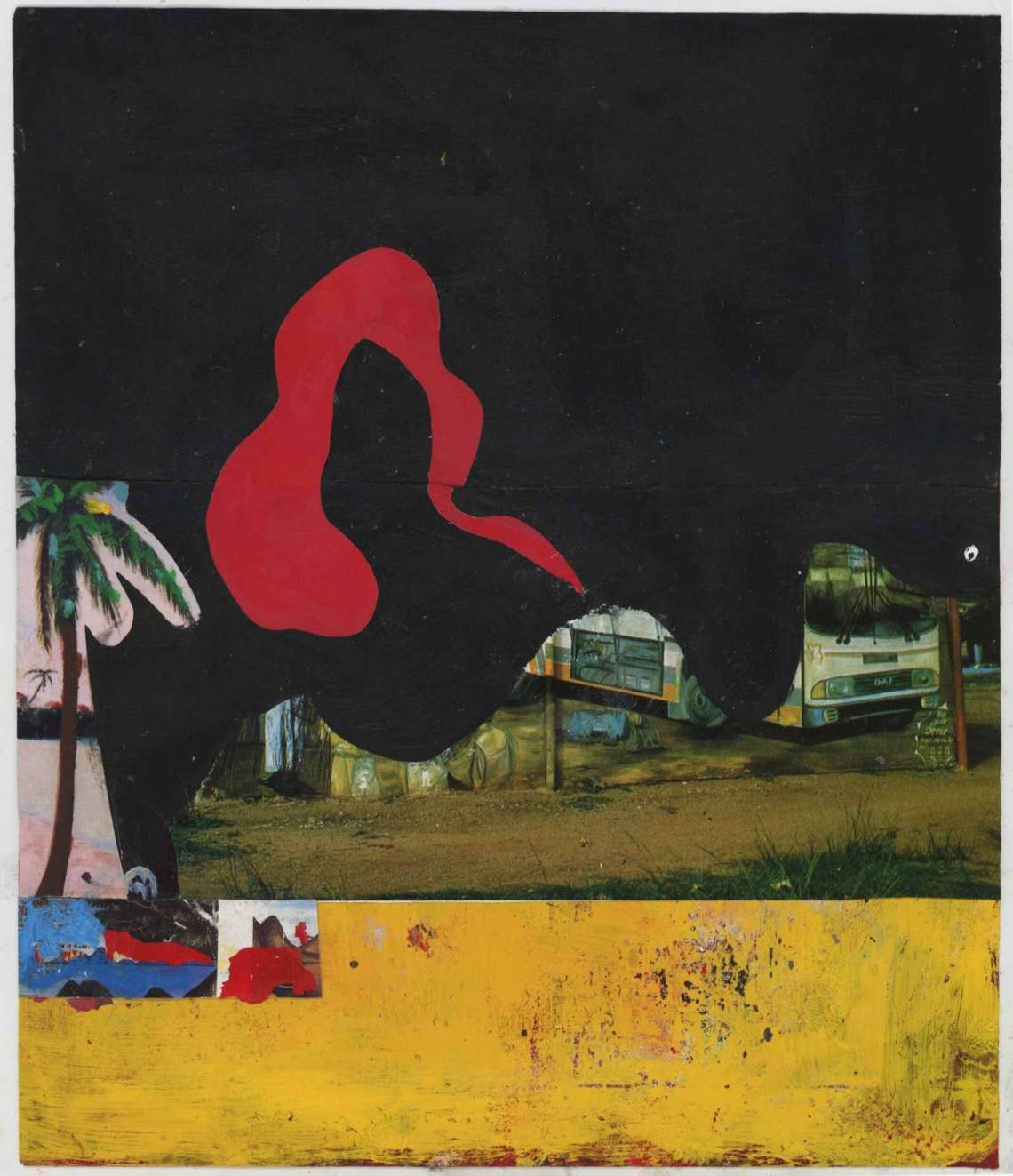

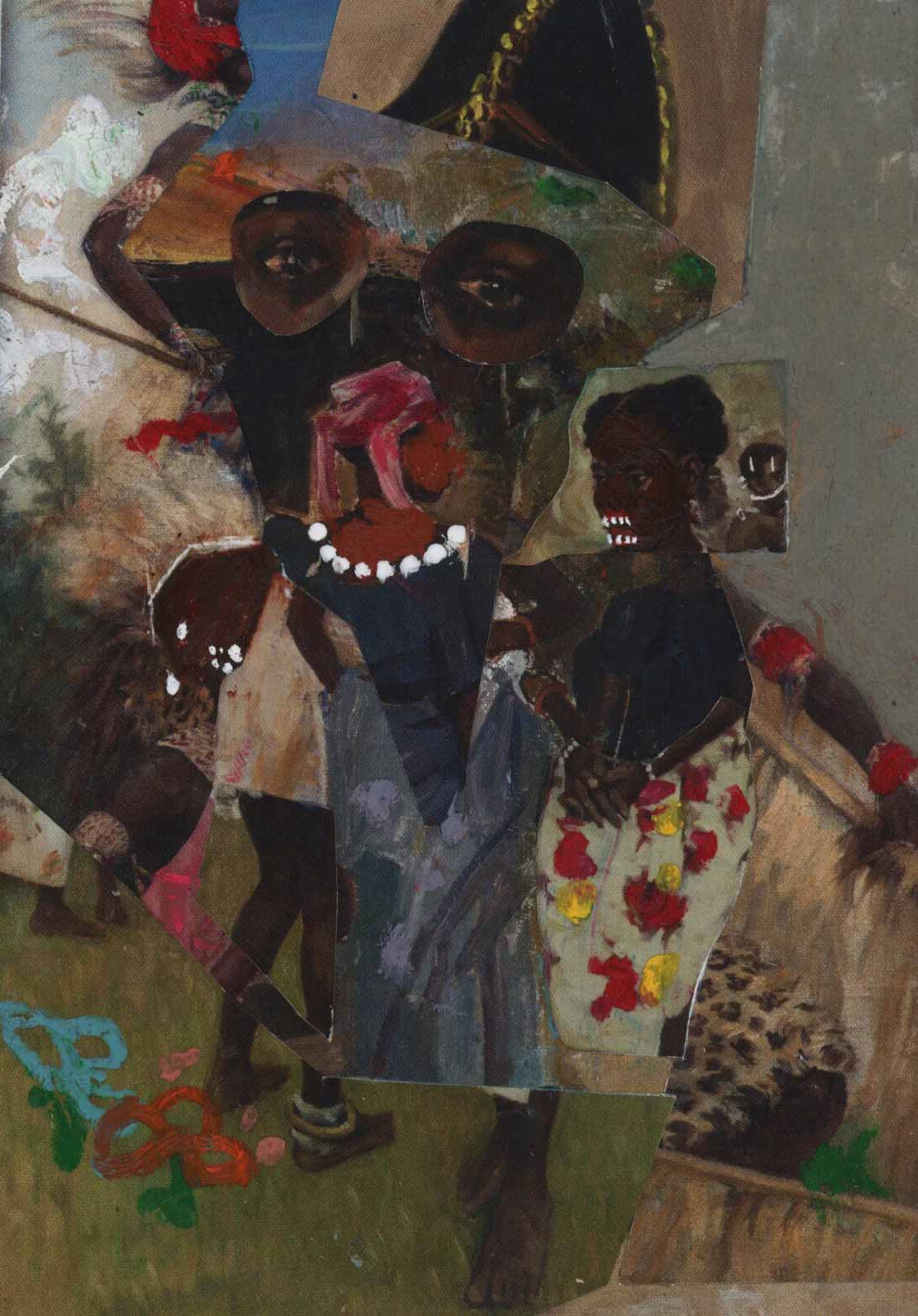

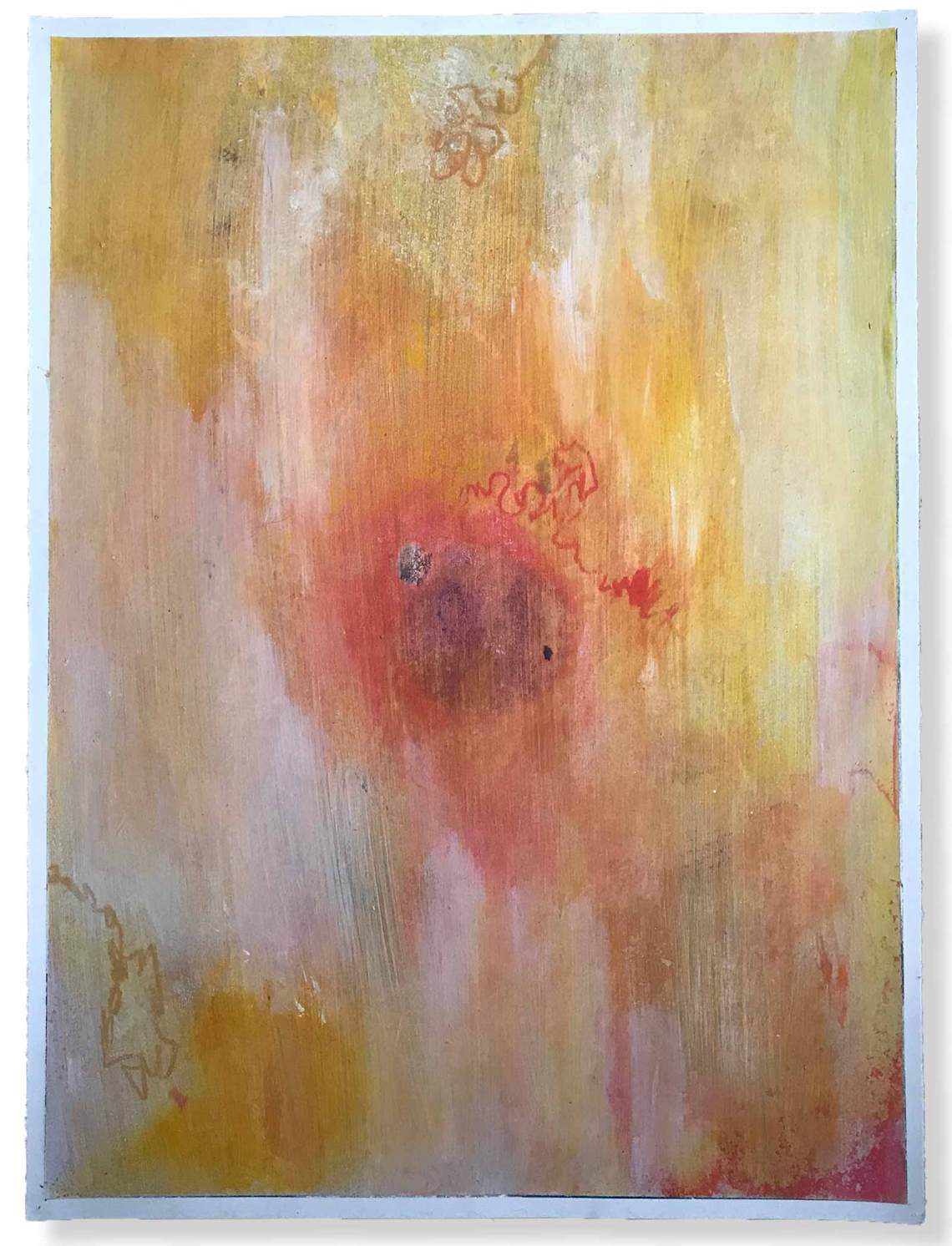

On one of the first spring-like Sundays this year, Baptist worried the weather might dissuade people from coming indoors. Instead, the opening of “Beauty in the Unknown” was packed with over a hundred people, both locals and visitors from out of state. Some were devotees of the gallery’s refreshingly curated Instagram account who were visiting for the first time. Others joined off the street out of curiosity. The two-person exhibition features the work of Brooklyn-based artists Milo Matthieu, twenty-seven, and Austin Willis, twenty-four, both self-taught. The former is a collage painter, the latter a painter who uses raw pigments and spices such as turmeric and paprika on his canvases.

Advertisement

Matthieu’s works evoke unidentifiable environments, though certain images recur: a floating sun, grassy knolls, a gold cone. He fractures bodies and figures in grotesque configurations that are both gruesome and enticing. Willis’s work is at first glance more abstract, and quieter—yet, up close, the way his pigments appear pounded into the canvas suggests a kind of aggression. Baptist paired the two artists because of a shared sense of urgency she recognized in their works. They had never met before, but both were enthusiastic about the pairing once they saw their work on the walls. Their styles, though different, clearly complement each other. Several visitors at the opening thought all the work belonged to one artist.

While both are young black men working, like any artists, in response to their environments, the abstract nature of Matthieu’s and Willis’s works insists that their canvases be considered primarily for their beauty, skill, and technique. Whereas corrective interventions intended to address the underrepresentation of black artists often prioritize work with more obvious references to identity, the artistry on display at Medium Tings foregrounds the technical virtuosity and achievement of the work itself.

Back-to-back shows will keep Baptist busy until summer’s end, when she plans to pause and consider what’s next. “Medium Tings is an incubator for me as much as it is for the artists,” she says.

“Beauty in the Unknown” is at Medium Tings every Sunday from 1PM to 5PM, and by appointment, through May 13, and will be followed by an exhibition featuring performance artist Ayana Evans.