It was just over a week after a coalition of populist and right-wing parties won a majority of votes in Italy’s parliamentary election, and the former senior adviser to President Donald Trump sounded positively besotted as he gushed about the manliness and brio of Benito Mussolini. “He has all that virility,” Steve Bannon told The Spectator of London. “He also had amazing fashion sense, right, that whole thing with the uniforms.”

Given his own sartorial and hygienic proclivities—layering collared shirts and looking as though he hasn’t showered for days—it was strange to behold Bannon extolling interwar Italian couture. Social media feeds lit up with quips about the homoerotic subtext of Bannon’s Mussolini crush. This may have been an unexpected instance of a connection made between fascism and gay masculinism, but it is hardly without precedent. Gay men, closeted or otherwise, have featured prominently in fascist movements—despite the seemingly obvious contradiction between their sexual orientation and a political program that has usually been explicitly hostile to it. Ernst Röhm, for a time arguably the second most powerful Nazi leader, was gay—as were several senior figures in his paramilitary organization, the Sturmabteilung (SA).

In the postwar period, Michael Kühnen, a prominent German neo-Nazi who died of AIDS, noted that homosexuals were “especially well-suited for our task, because they do not want ties to wife, children and family.” Nicky Crane, a street-fighting activist in the British National Front, performed in gay pornography. The Austrian far-right leader Jörg Haider, a married family man, died in a drunk-driving accident on his way home from a gay bar, while the most famous book by the French National Front supporter Renaud Camus is Tricks, a chronicle of his one-night stands with men.

A contemporary American figure who has married a macho gay male identity with ultra-reactionary politics is Jack Donovan, a neo-pagan advocate of “anarcho-fascism” and a leader of the Wolves of Vinland, a Norse revivalist “tribe” whose members gather in forests to smear mud on themselves and sacrifice animals. Donovan is a self-described “barbarian” who despises femininity; in a 2006 book, he disavowed the term “gay” in favor of “androphile” (he now says he self-identifies as bisexual). Donovan has recently distanced himself from his former associations with white nationalism and alt-right leaders like Richard Spencer—though he still describes Spencer as a friend, someone “witty and stylish” with “balls.” Donovan’s disdain for effeminacy did not, however, prevent him from joining the self-described “faggot” Milo Yiannopoulos in a 2016 edition of the right-wing gadfly’s Breitbart-hosted podcast to discuss “their roles as gay provocateurs.”

Another prominent gay man on the far-right scene is James J. O’Meara, author of The Homo & the Negro, which, according to its publisher, “argues that the Far Right cannot effectively defend Western civilization unless it checks its premises about homosexuality and non-sexual forms of male bonding, which are undermined not just by liberals and feminists, but also by Judeo-Christian ‘family values’ advocates.” O’Meara is a proponent of the belief that Jews are engaged in a centuries-old conspiracy against Western civilization, for which libidinous and demonic blacks provide the muscle.

Although these figures have occupied, to a comical extent, extreme poles on the spectrum of gay male identity, from fey to butch, what they have in common is a callous disregard for those whom they consider their social, physical, intellectual, racial, or cultural inferiors. Their very visibility as avatars of the far right attests to the fact that, to a great extent, their openly avowed homosexuality makes them outliers in their movement. Far more often, historically and certainly today, gays have identified with the left. The nineteenth-century English poets Edward Carpenter and John Addington Symonds were passionate socialists who, in the universality of homosexuality, saw a means of transcending class barriers. “The blending of Social Strata in masculine love seems to me one of its most pronounced, & socially hopeful features,” Symonds wrote to Carpenter in 1893. “Where it appears, it abolishes class distinctions… If it could be acknowledged & extended, it would do very much to further the advent of the right sort of Socialism.”

In his 1871 ode to America’s young democracy, Democratic Vistas, Walt Whitman—whose ministrations to wounded Union soldiers were motivated by more than mere platonic interest—wrote of “Intense and loving comradeship, the personal and passionate attachment of man to man.” In a speech supporting the ill-fated Weimar Republic some fifty years later, the not-completely-heterosexual Thomas Mann remarked upon “that social eroticism which plays so large a part in Whitman’s democratism.” No one took to the “social eroticism” of democracy with more egalitarianism or vigor than the British Labour MP Tom Driberg, long suspected of being a spy for the Soviet Union. “What he wanted above all,” Christopher Hitchens once told me, “was to give free blowjobs to the working classes.” Today, while the influence of conservatives on the modern gay rights movement is too little acknowledged, the vast majority of gay activists identity with the progressive left.

Advertisement

Despite this fairly obvious empirical truth, fascism’s flourishing in predominantly male milieus has long led commentators to posit that there is an intrinsic homoeroticism in fascism’s veneration of masculinity and corresponding disdain for femininity, even that there is something homosexual about fascism itself. In her 1974 Review essay “Fascinating Fascism,” for example, Susan Sontag observed that “fascist art displays a utopian aesthetics—that of physical perfection.” While “left-wing movements have tended to be unisex, and asexual in their imagery,” fascist iconography holds a particular allure for gay men, she wrote, as “extreme right-wing movements, however puritanical and repressive the realities they usher in, have an erotic surface” that idealizes the male form.

But an erotic attraction to politicized masculinity exists among only a small portion of right-wingers who happen to be gay. And given the way in which the medical and psychiatric professions long cast homosexuality as a social pathology, the theory of fascism’s inherent if latent homosexuality is rightly a contentious one. Throughout the twentieth century, both the extreme left and the hard right used accusations of homosexuality as a political smear, as a means of indicting their opponents as degenerates. In the early 1930s, Soviet propaganda portrayed homosexuality and fascism as naturally connected. The Brown Book of the Reichstag Fire and Hitler Terror, a Communist-produced tract that was translated into two dozen languages, alleged that the Dutchman found guilty of burning down the German parliament in 1933, Marinus van der Lubbe, was gay—a “vain, publicity-seeking tool” of “homosexual SA leaders.” (Nazi propaganda, meanwhile, portrayed the Reichstag Fire as a Communist plot.) In the same year, Stalin made male homosexuality a criminal offense in the USSR, and the Russian writer Maxim Gorky went so far as to proclaim: “Eradicate the homosexual and fascism will disappear.” (Upset at the gay-baiting of his leftwing comrades, the German writer Klaus Mann, son of Thomas, bemoaned how “People are in the process of making a scapegoat out of ‘the homosexual,’ the anti-fascists’ equivalent of ‘the Jew.’”)

The association of homosexuality with fascism was not limited to the extreme left. In a wartime study entitled The Mind of Adolf Hitler, published by the Office of Strategic Services (the OSS, forerunner of the CIA), the psychoanalyst Walter C. Langer hypothesized on the supposed attraction fascism held for homosexuals:

The fact that underneath they feel themselves to be different and ostracized from normal social contacts usually makes them easy converts to a new social philosophy which does not discriminate against them. Being among civilization’s discontents, they are always willing to take a chance of something new which holds any promise of improving their lot, even though their chances of success may be small and the risk great. Having little to lose to begin with, they can afford to take chances which others would refrain from taking.

In the aftermath of World War II, the theorists of the Frankfurt School—themselves refugees from Nazi Germany—further developed this psychological theory of male homosexual affinity with fascism. Gay men, they proposed, longed for a pre-Oedipal father figure to instill order and discipline: a Führer. Totalitarianism and homosexuality “belong together,” wrote Theodor Adorno—though the elision here, from fascism specifically to totalitarianism in general, was telling. As Cold War paranoia took hold of American society, homosexuality came to be associated less with fascism and more with the new menace of Communist subversion and treason. The Lavender Scare of the early 1950s, which saw thousands of suspected gay men and women summarily fired from federal employment, proceeded apace with the Red Scare of McCarthyism. As the Columbia historian of sexuality George Chauncey put it: “The specter of the invisible homosexual, like that of the invisible communist, haunted Cold War America.”

The Cold War witch-hunt of homosexuals was cruel and unwarranted. The best conclusion about this twentieth-century left-right tussle of blame and smear is that homosexuality itself has no ideology, no intrinsic political bias. But just as today many gay people see their sexual orientation as conducive to a left-wing political identity, according to which membership in a marginalized minority group instills one with a progressive social conscience, so for a much smaller number (almost exclusively of gay men) has homosexuality been central, or at least not incidental, to why they have placed themselves on the extreme opposite end of the political spectrum. And for this peculiar cohort, that political positioning seems to hinge upon the same axis of affect as attracts many gay people to the left: whereas the latter preach a love for the masses, the former feel an aversion to them. For those already in the mode of believing themselves superior by virtue of their sexual desire—in O’Meara’s words, “Homos indeed form a natural elite”—it is not a stretch to consider their race or nation in the same, supremacist light. If fascism has had an allure for gay men, it is anti-egalitarianism that provides the connective tissue.

Advertisement

*

This belief that homosexuality belongs to an elite caste, whose select adherents are members of an exclusive fraternity existing above the heterosexual masses and destined for greatness, is a theme recognizable in several prominent homosexual writers and figures throughout history and across cultures. The gay American architect and early Nazi enthusiast Philip Johnson, displayed, according to the author Marc Wortman, “a personal snobbery toward mass democratic society.” (Upon the German invasion of Poland, Johnson wrote that “The German green uniforms made the place look gay and happy,” albeit using “gay” in the earlier, non-homosexual sense of the word.) D.H. Lawrence expressed a hatred for democracy (“Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity,” he wrote, was a “three-fanged serpent”) and posited a Nietzschean understanding of same-sex relations, contending that “nearly every man that approaches greatness tends to homosexuality, whether he admits it or not.” Bemoaning the demise of dandyism, a way of life hardly exclusive to homosexuals but one disproportionately adopted by them, Baudelaire had blamed, “the rising tide of democracy, which spreads everywhere and reduces everything to the same level,” which “is daily carrying away these last champions of human pride.”

The idea of a homosexual elite allied with an authoritarian politics was initially advanced in the form of the Männerbund (men’s associations) of late Wilhelmine and Weimar Germany. In his cultural history of that era, Gay Berlin: Birthplace of a Modern Identity, the historian Robert Beachy details the surprising political diversity of early homosexual activists, many of whom were far right nationalists. The aftermath of World War I “helped to catalyze strains of masculinist ideology,” he writes, as “demoralized German troops” returned home “to explore the homosocial friendship and same-sex eroticism they had discovered in the trenches.” While the most renowned figure from that period remains the sex researcher Magnus Hirschfeld, a cosmopolitan, Jewish Social Democrat (whose 150th birthday will be celebrated May 14 at a symposium in Berlin), he existed alongside a coterie of hyper-masculine, authoritarian-minded writers and thinkers who “helped to assimilate homoeroticism to a nationalist, anti-democratic politics.”

Hirschfeld’s Scientific-Humanitarian Committee was far ahead of its time in positing homosexuality as a fixed identity, and his Institute for the Science of Sexuality, of which the Committee was part, was promptly destroyed by the Nazis after their seizure of power in 1933. Whereas Hirschfeld was interested in exploring the whole diverse array of sexual and gender expression—a panoply including lesbianism, “transvestism” (a term he invented), and effeminacy among gay men—the architects of the Männerbund prized masculinity, of which no purer form could be found than in the Frontgemeinschaft (front-line comradeship) of the World War I trenches. One of the intellectual leaders of the movement, Benedict Friedländer, contended that homosexuals constituted a class of Übermenschen, driven to greatness by the revolutionary nature of their forbidden desire:

Any repression of deep-seated physiological or physical tendencies harms the body and spirit… Consequently, we can understand why the great men of post-classical and recent times have so often sinned against both custom and the law on this particular point [homosexuality]: had they accommodated themselves on law and custom and sinned against their own nature, they might not have accomplished the achievements that have made their names immortal.

One organization promoting such theories, its sense of superiority elucidated by its very name, was the Community of the Special. Founded by the writer Adolf Brand, who had also started the world’s first regular gay publication, Der Eigene (“The Unique”), in 1896, the Community of the Special aimed to create “an elite vanguard of superior German men,” according to Beachy, “who would lead [a] renewal” of German nationalism. “Implicit was a strong suspicion of Weimar democracy and Reichstag debate, as well as latent and often explicit anti-Semitism,” as non-traditionally masculine homosexuals were conflated with lesbians, Jews, Communists, and Social Democrats as enemies of the German volk. In 1923, when campaigners were advocating the repeal of Paragraph 175 (the Wilhelmine-era law proscribing homosexual conduct, which the Nazis would later use to persecute gay men), the Community of the Special abstained—on the grounds that it did not want to divide conservative nationalist forces on this issue of sexuality as France began its postwar occupation of the Ruhr valley.

Another prominent Männerbund figure, Hans Blüher, wrote a three-volume study celebrating the homoeroticism of the Wandervögel, a German proto-boy scouts. When conservatives attacked him, Blüher overcompensated by adopting an extravagant German nationalism, eventually becoming one of the most notorious anti-Semites of the Weimar era. (According to historian Claudia Bruns, Blüher was one of the first figures to use the term Konservative Revolution to describe the array of reactionary forces that eventually toppled the Weimar Republic.) Figures like Friedländer, Blüher, and Brand were not a mere curiosity among politically active homosexuals in Germany at the time. Beachy cites a 1926 survey of 38,000 members of the League for Human Rights, one of Weimar’s leading homosexual organizations, which found that 12,000—roughly one-third—belonged to volkisch right-wing parties.

The most infamous figure to emerge from the milieu of the German Männerbund was Ernst Röhm, a barrel-chested, scar-faced veteran of World War I and co-founder of the SA, the gang of Nazi thugs colloquially known as “Brownshirts.” Surrounding himself with young, virile men looking for a fight, Röhm didn’t hide his homosexuality and, initially, his close friend Adolf Hitler was willing to tolerate it. (Part of the reason the Nazis incinerated the archives of the Institute for the Science of Sexuality so quickly after assuming power, Hirschfeld later surmised, was to destroy the records he had amassed from homosexual members of the SA who had volunteered for his studies.) But eventually Hitler began to see the SA leadership as a threat to his absolute power. In 1934, he ordered “The Night of the Long Knives,” in which Röhm and dozens of his SA comrades (some allegedly found in bed with one another) were executed.

Though the Nazi leadership carried out the Night of the Long Knives to eliminate a rival power base, it later claimed a desire to stamp out homosexual debauchery as an ex post facto justification for the purge. “A sect that was at the heart of a conspiracy not only against the normal conceptions of a healthy people, but also against state security” was how Hitler described Röhm and his circle. The image of the SA as a den of homosexual iniquity has lived on in popular culture; in his 1969 film The Damned, Luchino Visconti depicted the Night of the Long Knives as a gay bacchanal culminating in a gangland-style slaughter. It has also served more slanderous purposes: while the myth of a homosexual inclination to fascism may have originated with socialists and Communists, it has today been revived by some ultra-conservative polemicists intent on branding Nazism an outgrowth of progressive social and sexual values. Scott Lively, a pastor who has called for the criminalization of public advocacy of homosexuality,” has also co-authored a revisionist tract claiming that Nazism was a homosexual conspiracy. Dinesh D’Souza, who had the temerity to tweet last year that “Hitler was NOT anti-gay,” contends that the “Nazi atmosphere” of the early 1930s “far more closely resembles that of the Village Voice or the Democratic National Convention than it does the National Review or the Trump White House.”

The gay flirtation with Weimar-era rightist movements would end tragically, of course, not just for those homosexuals who joined Nazi ranks in the mistaken belief that Hitler would create a New Order in which they would be protected, but also for the thousands of gay men imprisoned and killed under the Nazi regime. “The many homosexual men who embraced the Nazi cause misapprehended the centrality of Nazi racialist doctrine and how homosexuality appeared to threaten it,” Beachy observes. “Viewing Nazis as the literal embodiment of the homoerotic Männerbund, many were blinded by the homoeroticism of the masculinist ideologies.”

*

For Jack Donovan, though, the ultimate paragon of “homofascism” (my term, not his) is not Röhm but a quite different martyr to the cause. Prominent on Donovan’s website, amidst pages promoting books entitled Becoming a Barbarian and The Way of Men, is a section devoted to Yukio Mishima. One of Japan’s most influential postwar writers and certainly its most popular among Western audiences, Mishima was astoundingly prolific. By the time of his dramatic death by suicide in 1970 at the age of forty-five, he had authored eighty plays, twenty-five novels, and acted in multiple films. Widely-tipped to win the Nobel Prize for Literature, Mishima earned the accolade “Leonardo da Vinci of contemporary Japan” from an Associated Press correspondent. He was also, and remains, a major intellectual influence on the Japanese nationalist far right.

According to Mishima, the “moral confusion of the postwar period” in Japan could be attributed to the abolition of the Emperor system and abandonment of the country’s martial virtues. In many interviews and essays, Mishima rehearsed his arguments against democracy and in favor of authoritarian rule. “At the end of freedom is the fatigue and boredom of the welfare state,” Mishima declared, lamenting the move away from feudalism—with its rigid hierarchies and social conventions—to liberal democratic capitalism, which granted freedoms that the vast majority of people were too irresponsible to exercise. The postwar debasement of the samurai code had led to the feminization of Japan, degenerating a land of warriors into a “nation of flower arrangers.” Under American occupation and cultural influence, Japan had become a “lukewarm land” that was “drunk on prosperity” and reduced to “an emptiness of spirit.”

In 1968, with the support of the Japanese government, Mishima created his own paramilitary, the Tatenokai (or “Shield Society,” whose English abbreviation just happened to be SS). Its purpose was to restore an appreciation for the militarism and emperor worship that were discredited after leading Japan into the hellfire of World War II. “Mishima dreamed of a better world,” Donovan writes admiringly, “a world where the Emperor was a god on Earth protected by Mishima’s own spiritual army, the Tatenokai.”

Though it goes unsaid in Donovan’s encomia, it can hardly be a coincidence that the American pagan tribalist is drawn to the long-dead Japanese author because of the latter’s exploration of homosexual themes. Mishima never publicly acknowledged himself as a homosexual, abjuring the modern identity the word imputes, and married a woman with whom he fathered two children. But his first novel, Confessions of a Mask, describes the sexual awakening of a young gay man, and Mishima never did anything to dissuade readers from concluding the book was autobiographical. (Nor did he do much to dissuade other gay men. “Mishima first caught the eye of the faggot contingent of the Occupation of Japan in 1945,” Faubion Bowers, General Douglas MacArthur’s gay personal interpreter, recalled in a tribute published after Mishima’s death.) In Confessions, the barely-disguised protagonist writes of his first orgasm, stimulated by Guido Reni’s painting of the martyred Saint Sebastian. That image, simultaneously erotic and violent, would transfix Mishima for the rest of his life and inspire much of his work and philosophy.

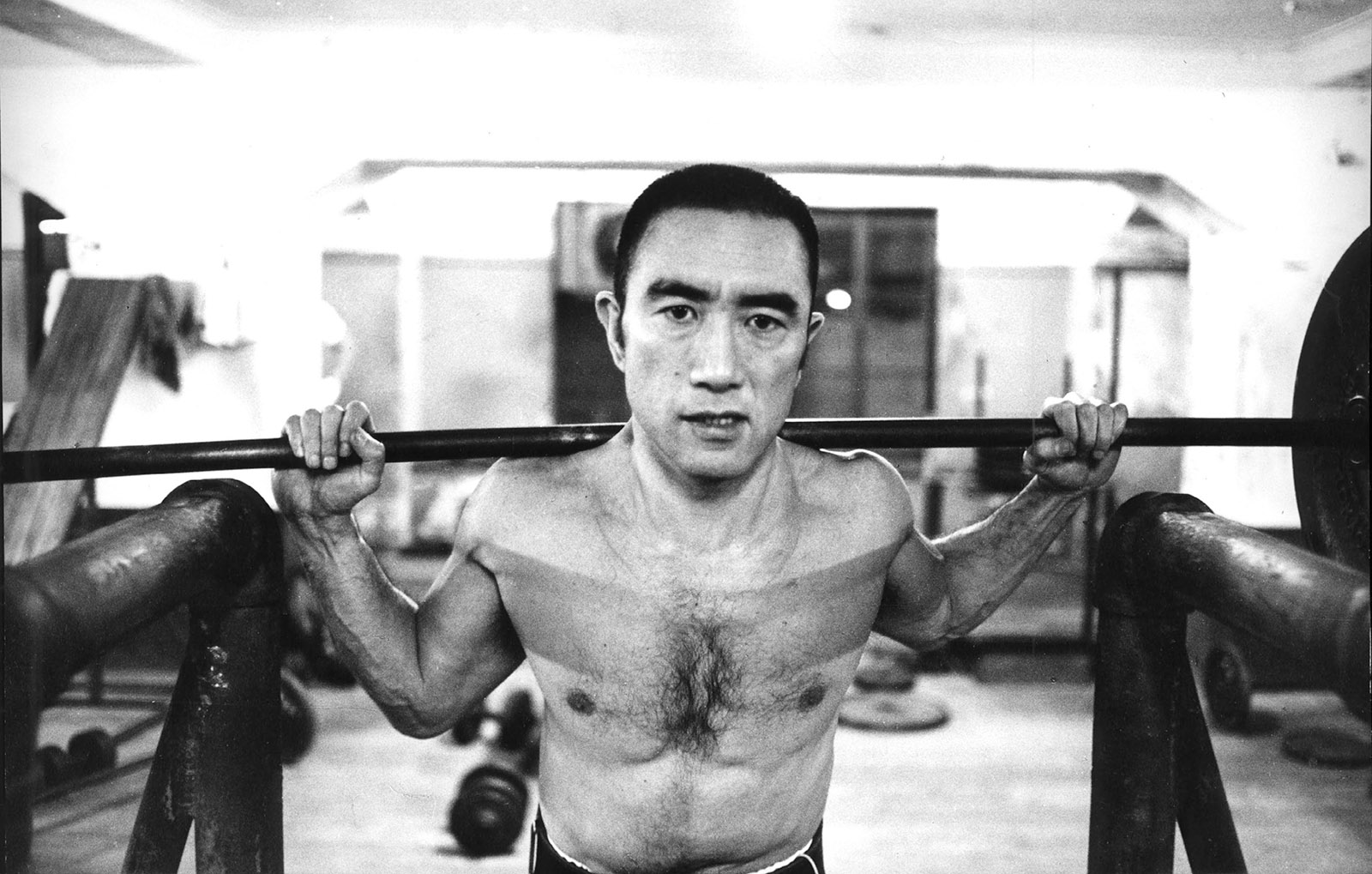

To wit, beauty and martyrdom, and the intertwining of the two, obsessed Mishima. (Another biographer recalled Mishima describing himself as a “beauty’s kamikaze squad.”) From the age of thirty until his death, Mishima devoted himself to bodybuilding, boxing, and Kendo (a form of Japanese fencing), and he proudly displayed his physique for homoerotic photo shoots, once even posing as the figure that had haunted him since childhood: Reni’s Sebastian. (Another, of him leaning seductively against a Honda motorcycle in a pair of briefs, could have easily appeared in a gay beefcake magazine.) In the 1968 essay “Sun and Steel,” Mishima explained the importance of attaining “physical perfection” in his pursuit of becoming a “man of action” with a “romantic impulse toward death.” As for those who mocked his fascistic vision, “the cynicism that regards hero worship as comical is always shadowed by a sense of physical inferiority.” Discussing that essay in the Review in 1971, Gore Vidal cattily concluded that “I only regret we never met, for friends found him a good companion, a fine drinking partner, and fun to cruise with.”

The decrepitude of old age—an aesthetic failing, above all—was one reason Mishima decided to kill himself at the age of forty-five. The others had to do with his politics and life philosophy. On November 25, 1970, Mishima attempted to rouse Japan from its liberal-democratic exhaustion with an act of futile martyrdom. Along with four members of his Shield Society, decked out in uniforms of his own design (which, Bowers wrote, “always reminded me of nothing so much as the costumes Nixon wanted for his private, ceremonial guard”), Mishima paid a visit to the Tokyo headquarters of the Japanese Self-Defense Forces. After the quintet tied the commandant to his chair and barricaded the office doors, Mishima stepped out onto the balcony to tell a group of incredulous soldiers assembled below that he was launching a coup to restore the Emperor and to revoke the country’s American-imposed pacifist constitution:

We have seen postwar Japan stumble into a spiritual vacuum, preoccupied only with its economic prosperity, unmindful of its national foundations, losing its national spirit, seeking trivialities without looking to fundamentals, and falling into makeshift expediency and hypocrisy.

Eliciting only bemused confusion and laughter from the soldiers below, Mishima went back into the office, where he performed the ritual act of seppuku: kneeling on the office floor, he disemboweled himself with a knife, after which one of his young comrades (and rumored lover) severed his head with a sword.

Donovan’s Mishima tribute site is entitled, apparently without irony, “Headless God.” On another tribute page, Donovan can be seen posed in the manner of Mishima preparing to commit his final act, bowing with hands on knees before a shotgun in the place of a sword. “No one remembers moderation or half-measures,” Donovan writes. “GO ALL THE WAY.” In Mishima, Donovan sees a heroic figure who was devoted to physical perfection, shared his disgust at the unheroic mediocrity of modern existence, and sacrificed his life for a cause. Mishima was “a man who transformed himself, who followed his own aesthetics and ideals to their natural final conclusion,” Donovan writes. “Americans tend to think of suicide in terms of retreat, but Mishima’s suicide was quite the opposite. It was bold and brave. How many readers could truly say they would cut their own stomachs open to make a point?”

What postwar Japan and a feckless Emperor were to Mishima, multicultural, postindustrial America and the showman Trump are to Donovan. “Sooner or later, white American men are going to have to deal with the fact that daddy isn’t coming home,” a resigned Donovan wrote in a 2016 piece entitled, “No One Will Ever Make America Great Again.” Mishima remains a figure of admiration for right-wing extremists of many stripes. His visage adorns the trucks of Japanese nationalists who blast propaganda slogans outside the Chinese and Korean embassies, and other fans include: the Bosnian Serb war criminal Radovan Karadzic; the gay lead singer of the neo-folk band Death in June (named after the Night of the Long Knives and accused of promoting fascist messages in its lyrics and insignia); and Dominique Venner, the French far-right author who committed suicide in Notre Dame cathedral on the eve of France’s legalizing same-sex marriage in 2013. After Venner’s death, his publisher compared him to Mishima and stated that Venner’s last book would be titled A Western Samurai.

Mishima’s attraction to fascist ideas was more than merely aesthetic. Langer’s analysis that, because “underneath they feel themselves to be different and ostracized from normal social contacts,” homosexuals make “easy converts to a new social philosophy” like fascism was obviously an egregious generalization. But the thesis that some gay men have been attracted to fascist ideology in pursuance of forming a reactionary homosexual vanguard is not necessarily wrong as applied to certain individuals, one of them being Mishima. Through his worship of the body, obsession with male beauty, misogyny, and contention that homosexuals formed an elite, Mishima developed something of an overarching theory as to why gay men belonged on the far right: as a despised and misunderstood minority, they should fear democracy and ally with the forces of reaction, ingratiating themselves with an authoritarian order.

The closest Mishima ever came to advancing this theory explicitly was in his novel, Forbidden Colors, which he published in 1951 at the age of twenty-five. It tells the story of an aging and virulently misogynistic writer, Shunsuke, who tries to exact revenge on the female sex by persuading an impressionable and impossibly beautiful young gay man named Yuichi to engage in affairs with various women and break their hearts. Much of the story takes place amidst the gay demimonde of postwar Tokyo, its bars and private parties, with which, per Vidal, Mishima was intimately familiar.

“He was coming to the inescapable conclusion that society is governed by the rule of heterosexuality, that endlessly tiresome principle of majority rule,” Mishima writes of Yuichi early in the novel. Everywhere he looks, the young man sees the ravages of this “majority rule,” or democracy, and feels nothing but contempt. Cruising for sex in a park, he is struck by the “ironic charity that a public place like this, symbol of the principle of majority rule, should benefit such a small number of people.” Not even the day of rest is spared from this misanthropic analysis. “A homosexual’s Sunday is pitiful. On that day, all day, no territory is theirs,” Mishima observes:

Go to a theater, go to a coffeehouse, go to the zoo, go to an amusement park, go to town, go out to the suburbs even; everywhere the principle of majority rule is lording about in pride. Old couples, middle-aged couples, young couples, lovers, families, children, children, children, children, children and, to top it off, those blasted baby carriages—all of these things in procession, a cheering, advancing tide.

Clearly, this written before the advent of brunch.

To Mishima, homosexuals constituted a superior class, unburdened by any longing for noisome, useless women. A heterosexual character “berated himself that he was so plebeian as not to possess so refined a nature” that would incline him toward homosexuality. At the bar where Yuichi goes, Mishima writes, the patrons “dreamed a dream of a simple truth… that man loves man would overthrow the old truth that man loves woman. Only the Jews were a match for them when it came to fortitude… The emotion proper to this tribe gave birth to a fanatical heroism during the war.” Here, Mishima embraces the concept of the warrior homosexual—a concept that can be traced to the ancient Greeks and was also prevalent among the Samurai—a man whose romantic and erotic love for his comrades make him a superior fighter.

Suicide is not the taboo in Japan that it is in the West, and Mishima remains a figure of renown in his native land. To a bemused Western observer like Vidal, however, the writer, his works, and his staged exit had the air of high camp. At the height of the AIDS crisis in 1987, a gay activist named Michael Swift published a satirical essay entitled, “Gay Revolutionary,” which gently mocked Mishima’s homosexual supremacism. Addressed to a homophobic society, it declares, “We shall raise vast private armies, as Mishima did, to defeat you. We shall conquer the world because warriors inspired by and banded together by homosexual love and honor are invincible as were the ancient Greek soldiers.” Though this author clearly saw Mishima as a silly and slightly menacing character, he also noticed something noble in the Japanese writer, a righteous defiance that could prove useful for a community fighting societal hatred and disgust in the face of a deadly epidemic. “Highly intelligent, we are the natural aristocrats of the human race, and steely-minded aristocrats never settle for less,” the essay continues. “Those who oppose us will be exiled.” Among his other posthumous accomplishments, Mishima may be the only figure in history appropriated as both a gay and a far-right icon.

As was, and remains, the case for other gays on the far right, Mishima’s embrace of authoritarian politics emanated from a disaffection with society, a disaffection he also expressed through his fiction. According to the literary critic Peter Wolfe, the “cultural and spiritual alienation” experienced by the homosexual characters of Forbidden Colors is “a function of [their] being gay.” Such a sense of alienation is one that all gay people, as sexual minorities in societies that do not fully accept them, inevitably experience. The question for the modern homosexual, in this analysis, is whether he considers “being among civilization’s discontents” a reason to alter or reify the society he inhabits.

From D.H. Lawrence to the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century German Männerbund, Yukio Mishima to Jack Donovan and beyond, some homosexual men have chosen the latter approach. Rather than join with other disadvantaged groups and victims of discrimination in working toward a more equitable society—as the modern gay rights movement eventually did—these men endorsed slightly more inclusive forms of authoritarianism that would tolerate them. Their extreme anti-egalitarianism has echoes in certain unsavory aspects of modern gay culture—namely, an obsession with physical perfection (derogatorily termed “body fascism”), conformism (the “Castro clone”), exclusivity (from the “no fats, no femmes” of post-Stonewall personal ads to the “no blacks, no Asians” provisos ubiquitous on gay dating apps), and misogyny (expressed not only in a revulsion toward women but also in the suppression of one’s own femininity). Much as “homofascists” have erected a series of supremacist hierarchies—of male to female, white to non-white, Aryan to Jew, imperial rule to liberal democracy—so have they positioned homosexuality as superior to heterosexuality.