The gripping and dramatic show “All Too Human: Bacon, Freud and a Century of Painting Life” merits its title: it is “all too human” in the tender, painful works that form its core. But “a century of painting life” promises something wider—does it smack of marketing, a lure to bring people in? In fact, the heart of the show is narrower and more interesting, illustrating the competing and overlapping streams of painterly obsession in London in the second half of the twentieth century. It shows us how, in their different ways, painters such as Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud, Leon Kossoff and Frank Auerbach, R.B. Kitaj, and Paula Rego redefined realism. In defiance of the dominant abstract trend, they teased and stretched the practice and impact of representational art. “What I want to do,” Francis Bacon said in 1966, “is to distort the thing far beyond the appearance, but in the distortion to bring it back to a recording of the appearance.” In this show, terms like “realism” and “human” take on new meaning and power.

The exhibition begins, cleverly, with some forebears of these London artists, pre-war painters who looked with intensity at the lives, settings, and landscapes that most affected them, and used paint in a highly personal way to convey not only what they saw, but what they felt. It feels odd, at first, to walk into a show that claims to be about “life” and find a landscape rather than a life-study, yet the urgent, textured use of paint in Chaïm Soutine’s earthy landscapes, as well as his distorted figures and the raw strength of The Butcher Stall (circa 1919), with its hanging carcasses, had a profound impact on Francis Bacon. In a similar way, all the works in this first room reach toward the future: Stanley Spencer’s portraits of his second wife, Patricia Preece, clothed and naked, stare out with the unpitying confidence of Lucian Freud’s early portraits. Sickert’s dark portrayals of London prostitutes—his attempt to give “the sensation of a page torn from the book of life”—anticipate the unsentimental nudes of Freud and Euan Uglow (no relation to me). David Bomberg’s layered, arid Spanish landscapes point toward the scumbled, perspectiveless scenes of Kossoff and Auerbach.

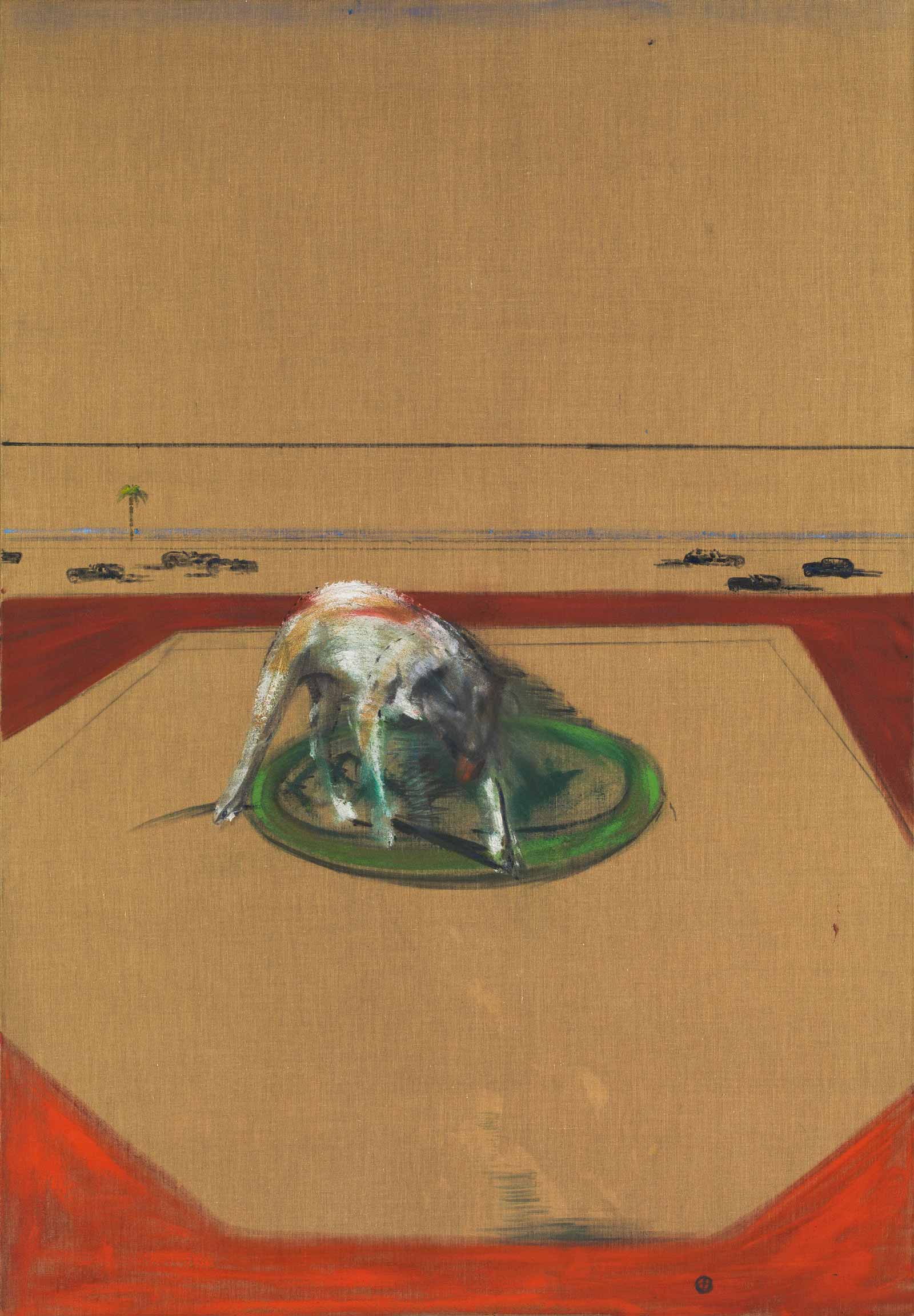

Nothing, however, prepares one for the tender ferocity of Bacon’s isolated, entrapped figures. In the earliest of these, the large canvas of Figure in a Landscape (1945), a curled-up, almost human form appears to be submerged in a desert—we see his arm and part of his body, but the legs of his suit hang, empty, over a bench. This is masculinity destroyed. The sense of desperation is even stronger in Bacon’s paintings of animals, such as Dog (1952), in which the dog whirls like a dervish, absorbed in chasing its tail, while cars speed by on a palm-bordered freeway, or Study of a Baboon (1953), where the monkey flies and howls against the mesh of a fence. In their struggles, these animals are the fellows of Bacon’s “screaming popes”: in Study after Velazquez (1950), a businessman in a dark suit, jaws wrenched open in a silent yell, is trapped behind red bars that fall like a curtain of blood. The curators connect Bacon’s postwar angst with Giacometti’s elongated statues, isolated in space, and to the philosophy of existentialism. Yet Bacon’s vehement brushstrokes speak of energy and involvement, physical, not cerebral responses. In Study for Portrait II (after the Life Mask of William Blake) (1955), you feel the urgent vision behind the lidded eyes. He cares, passionately.

This was a postcolonial as well as a postwar world, a point made abruptly by devoting a room to the work of F.N. Souza, who came to London from Bombay in 1949, and worked here until he left for New York in 1967. Despite Souza’s popularity at the time, and the range of sacred and profane references that link him uneasily to Bacon, his stark religious iconography feels out of keeping with the bodily compulsion of Bacon’s work and the new streams of influence shaping what R.B. Kitaj named “the School of London.”

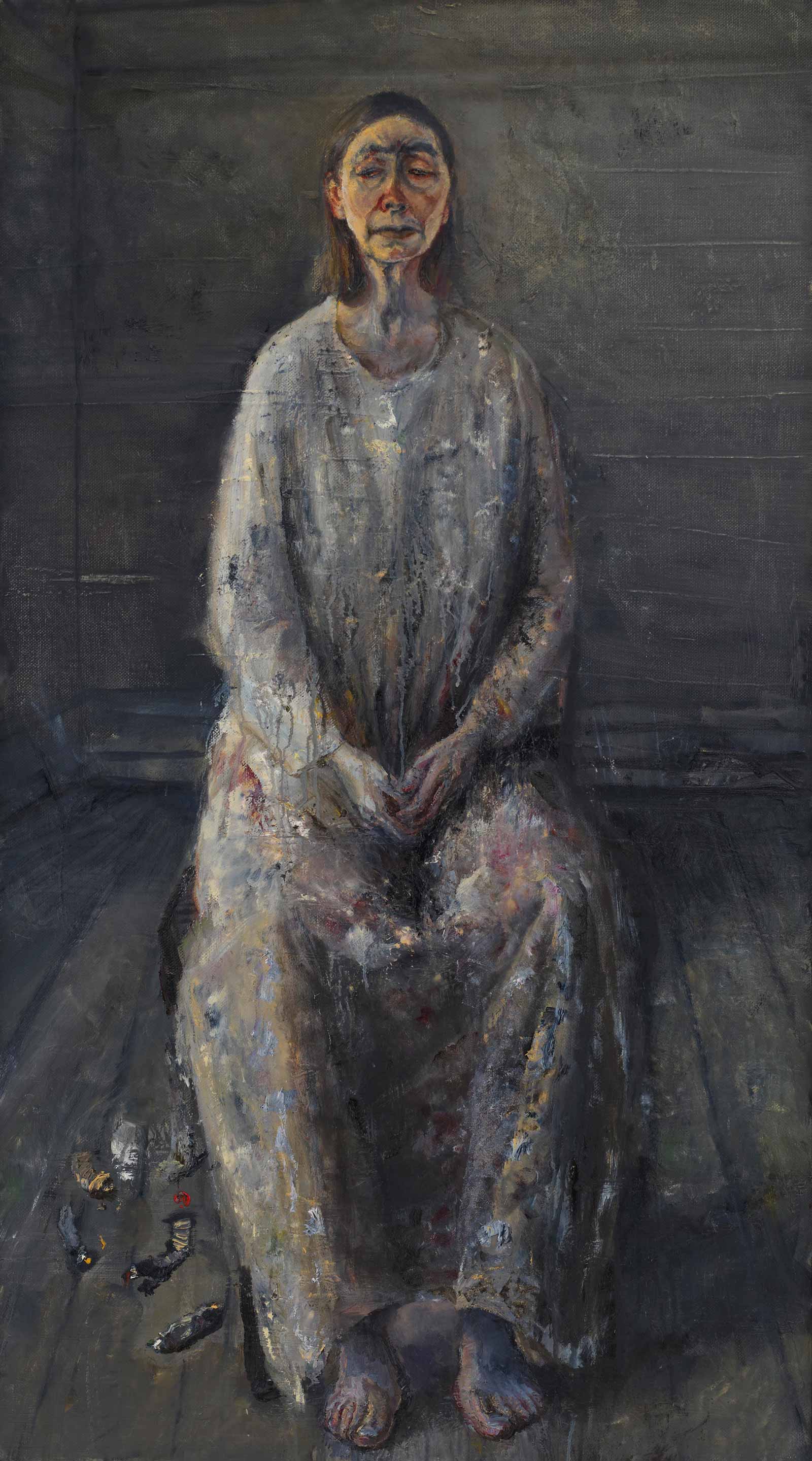

One of these streams flowed from the Slade, where William Coldstream was professor of Fine Art and the young Lucian Freud was a visiting tutor. Here, in a very different way to Bacon, you feel the pressure of flesh. Coldstream believed that artists should work without preconceptions, through minute, painstaking observation, fixing “reality” with measurement, allowing the subject to emerge slowly on the canvas. His Seated Nude (1952–1953) was painted over at least thirty sittings of about two hours each—no wonder the model looks glazed. His pupil Euan Uglow adopted this technique, setting his figures against a geometric grid. It gives them an eerie physicality. (I’m not the only person to stand in front of his 1953–1954 Woman with White Skirt and say, “Paula Rego.”) Uglow is famous for telling a model, “Nobody has ever looked at you as intensely as I have.” Over time, his control of detail and setting became obsessive, but his piercing gaze and careful technique remained, rendering his subjects at once solid and dreamlike, their inner spirit elusive but embodied.

Advertisement

In the 1950s, Uglow’s belief in the value of minute observation was shared by Freud, who admitted, as Emma Chambers writes in the exhibition catalogue, to a “visual aggression” toward his sitters: “I would sit very close and stare. It could be uncomfortable for both of us.” His paintings from this period, delicately wrought with a fine sable brush, are almost hallucinatory in their detail, with a Pre-Raphaelite veracity of sheen and texture. We see the softness of material, the fur of the dog. And how exposed and alarmed his first wife, Kitty Garman, looks in the extraordinary Girl with a White Dog (1950–1951), in her pale green dressing gown with one white, veined breast revealed.

At the same time as Coldstream was instilling in his students the virtues of precision and measurement, David Bomberg was inspiring his pupils at the Borough Polytechnic in South London from 1946 to 1953 with a far freer, more tactile approach. To Bomberg, painting was about the “feeling” and experience of form, not its mere appearance. His own work conveyed the sense of mass in fluid, sensuous oils, and young artists such as Frank Auerbach, Dennis Creffield, Leon Kossoff, and Dorothy Mead flocked to his classes. Often working outdoors, as Bomberg did, Auerbach and Kossoff painted the settings they knew, showing a new London rising from the old, driving across the canvas in slabs of paint and thick encrustations. Auerbach’s Rebuilding the Empire Cinema, Leicester Square (1962) and Kossoff’s Building Site, Victoria Street (1961) are so tactile that they make you want to trace the lines with your hand, while the sticky ridges of Auerbach’s Head of E.O.W. I (1959–1960)—so strong from a distance, so baffling up close—seem as much sculpture as painting.

Again and again in this exhibition, we move from the exchange of ideas and influences to the individual vision. Some works, indeed, are so drenched in emotion that they produce ripples of shock. The intimacy of Freud’s work is intensified when he moves, around 1960, from minute, close-up fidelity to large, expressive brushstrokes. In his later paintings, he catches the twist of muscles, the sweat on the skin, the pride and fullness of bodies in sleep, as in the great Leigh Bowery (1991), showing Bowery, a performance artist with a body of billowy corpulence, with his head slumped gently on his shoulder, or in Sleeping by the Lion Carpet (1996), where Sue Tilley—“Big Sue,” Bowery’s cashier at his Taboo night club and a benefits supervisor at the Charing Cross JobCentre—dozes safely before a predatory image.

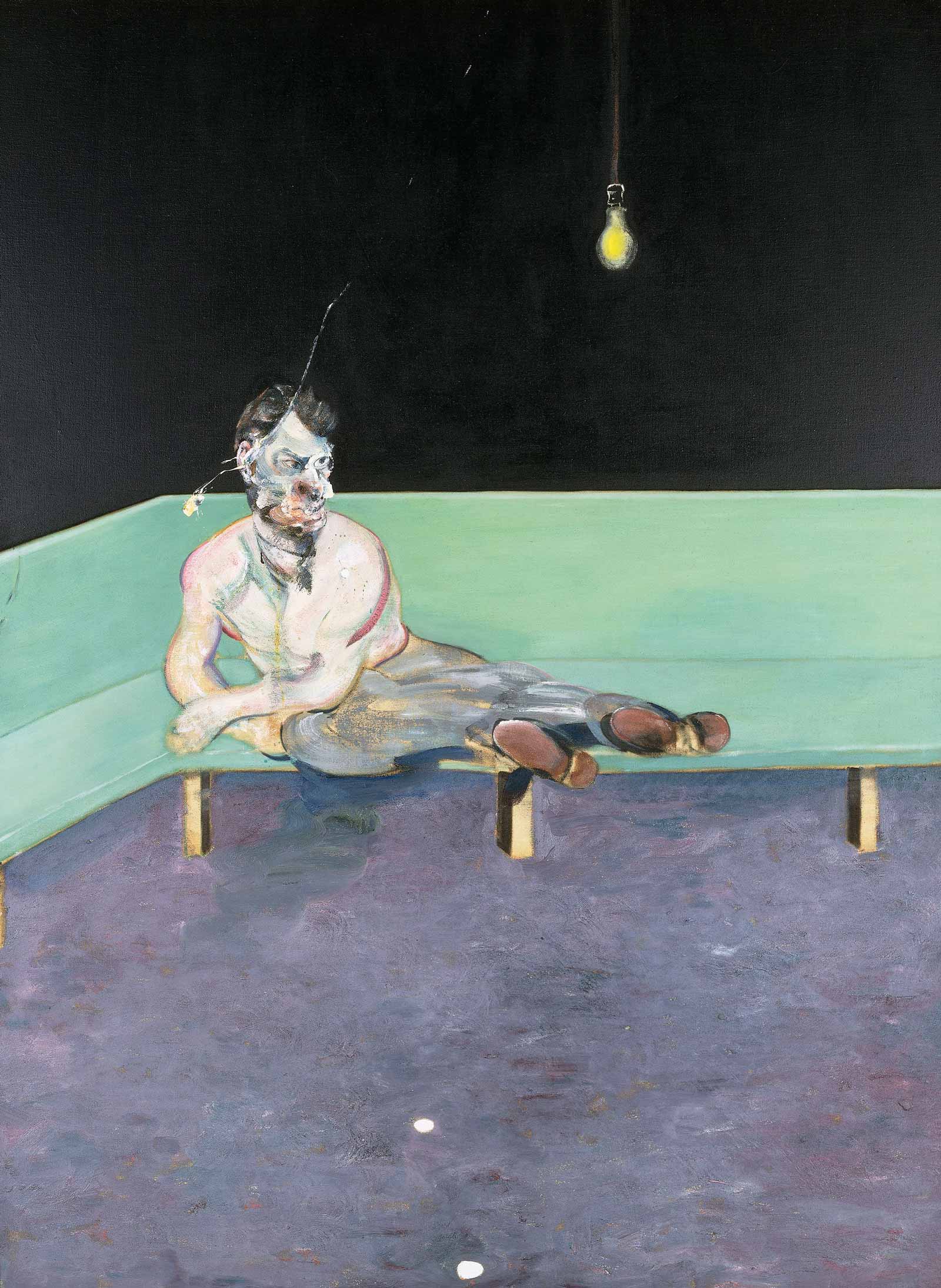

By the 1960s, when Freud was subjecting his models to hours and days of sitting, Bacon was standing back, using photographs rather than live models. One room here shows a selection of portraits he commissioned from the photographer John Deakin. These are direct, intimate, and suggestive, but when Bacon explores the human form, the effect is very different. Bodies and heads become twisted, swollen, contorted. In his Study for a Portrait of P.L. (1962), painted in the year of Lacy’s death, after ten years of their turbulent, sometimes violent relationship, the internal and sexual organs seem to bulge through their covering. Two years later, his Study for Portrait of Lucian Freud emphasized the strong torso, the fierce expression, the unnerving clarity of Freud’s gaze. These are psychological as much as physical studies. In the moving Triptych (1974–1977), an unusual outdoor, light-filled work, the body beneath the umbrella writhes on the deserted beach, as Bacon mourns the death of his lover, George Dyer. But beyond them, the clear sky suggests a slow, painful coming to terms with loss—the promise of new life , or at least oblivion, in the deep blue of the sea beyond?

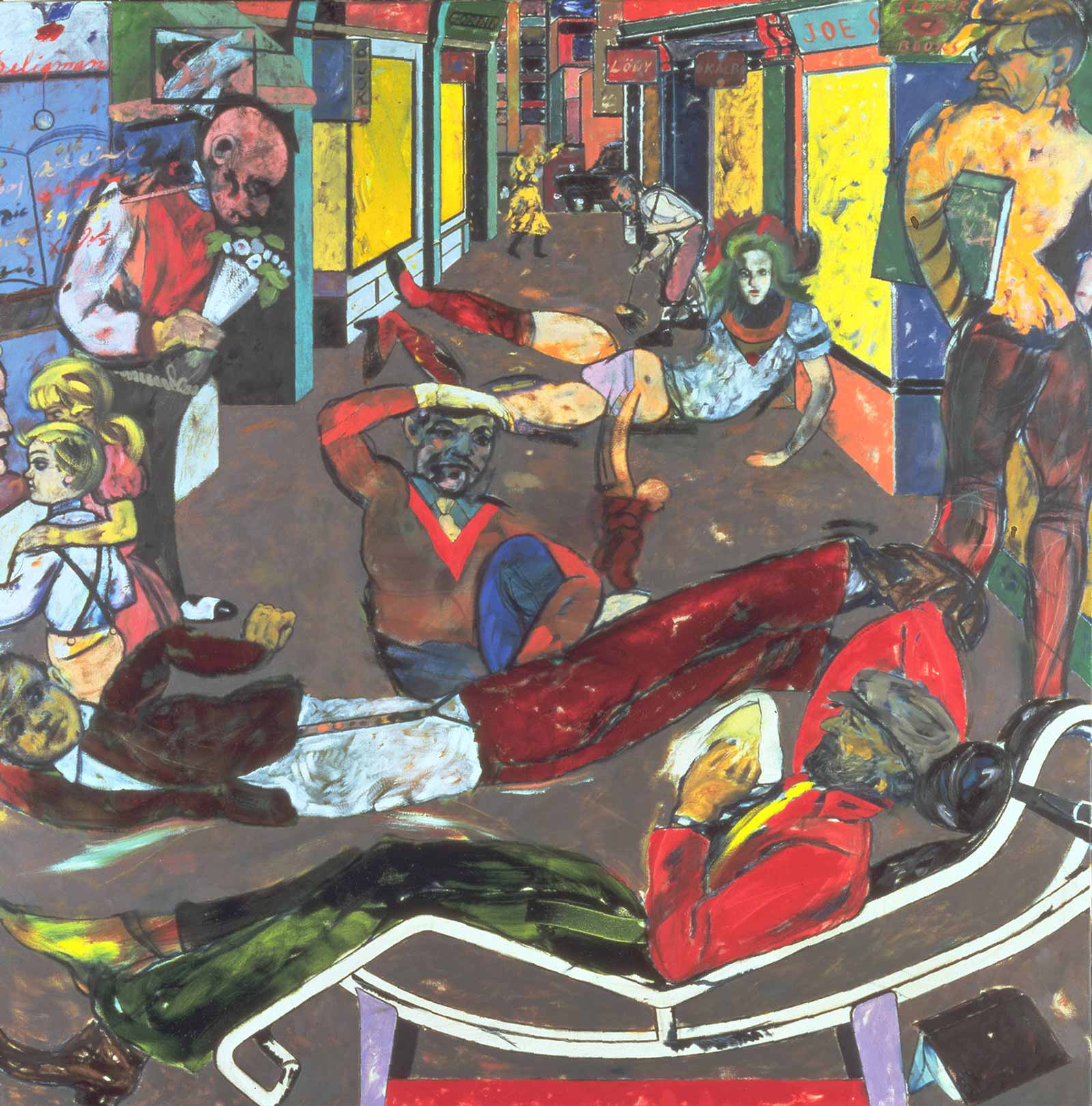

Bacon’s solitary figures are, paradoxically, imbued with a feeling of relationship. The same is true of Freud’s portraits, of his wife, his mother, his daughter, his friends. The intimacy of the family is also part of what it means to be “all too human.” Michael Andrews, for example, intrigued by Bacon’s use of photography, worked from a color photograph of a holiday in Scotland for his darkly beautiful Melanie and Me Swimming (1978–1979), spray-painted in acrylic. This feels like a moment swimming out of time into memory. And sometimes the sociability of London’s artistic life is itself commemorated. In Colony Room I (1962), Andrews painted the Colony Club, where Bacon, Freud, and Deakin drank with Soho’s artists and writers. “Life,” in the sense of a community, also fills R.B. Kitaj’s brilliant group scenes, such as Cecil Court, London W.C.2. (The Refugees) (1983–1984). His crowded, colorful The Wedding (1989–1993) celebrates not only his marriage to Sandra Fisher but his friendships—with Auerbach, Freud, Kossoff, and David Hockney, among others.

Advertisement

Hockney’s work is inexplicably absent here, and so, up to this point in the show, are works by women, apart from a blurry, atmospheric nude by Dorothy Mead. But suddenly, you turn a corner, and there is Paula Rego. The streams of the London School flow together. Rego came from Portugal when she was sixteen to finish her education, and from 1952 to 1956 she studied at the Slade under Coldstream, alongside Andrews, Uglow, and her future husband, Victor Willing. As Victor slowly declined from multiple sclerosis, her painting became increasingly personal. The Family (1988), painted in the last months of his life, shows two women helping him take off his jacket—yet there is a strange undertone here: they seem to be shuffling him into the grave. The feeling is curiously sinister, perhaps reflecting Rego’s awareness that women—always the carers—are often so intimate with death. The little shrine in the background may show George slaying the dragon, but above him stands St. Joan, the martyred, martial saint.

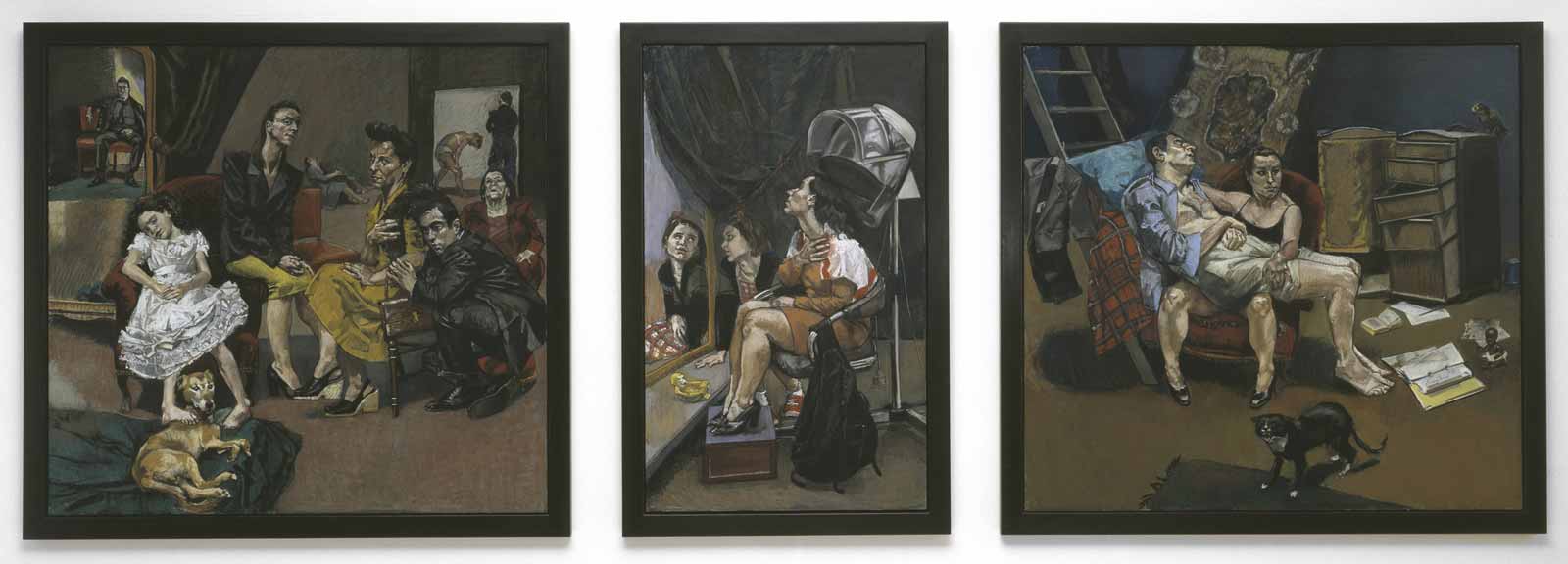

Rego has often used stories to uncover the depths of our humanity, exposing the shattered dreams and desires of women across time. In Bride (1994), the bride lies back awkwardly, as if her wedding dress were a strait-jacket. In the trilogy The Betrothal: Lessons: The Shipwreck, after ‘Marriage a la Mode’ by Hogarth (1999), Hogarth’s moral tale of greed and disease, a mockery of the dream family, is reworked in the fashions of her own childhood.

By contrast, the final room—apart from Celia Paul’s Family Group (1984–1986) and the powerfully interior Painter and Model (2012)—feels like a token addition, a nervous nod to gender and diversity. Jenny Saville, Cecily Brown, and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye are fine artists, but they belong in a different narrative. A misstep, yet “All Too Human” remains an extraordinary exhibition, full of works of deep seriousness and bold, brave fidelity to life. For me, it ends with Rego’s bitingly honest work. With her bold, distinctive use of outline and color, and her mighty sympathy for human pain and longing, her paintings show life in all its senses.

“All Too Human: Bacon, Freud, and a Century of Painting Life” is at the Tate through August 27.