When the painter Tsuguharu Foujita departed from Paris in 1931, he left a farewell letter for his friend the surrealist poet Robert Desnos. Foujita wrote about his third wife, Youki, whose legal name was Lucie Badoud. She also happened to be Desnos’s lover. Foujita, who was bound for Rio de Janeiro with the dancer Madeleine Lequeux, asked his friend to care for Youki and bequeathed to her all of his paintings, those of the era featured in “Foujita: Painting in the Roaring Twenties” at the Musée Maillol. At that time, Foujita was a highly successful painter associated with the bohemian circle of Montparnasse, later called “The School of Paris.” Throughout the 1920s in Paris, Foujita cut an arresting figure: a Japanese modernist as willing to trade on his own foreignness as he was to blend into his Parisian surroundings. “There are not a lot of artists,” author of the 1925 monograph on Foujita Michel-G. Vaucaire wrote, “who have reached a remarkable situation: of passing for a French painter in the eyes of the Japanese and for a Japanese in those of Westerners.”

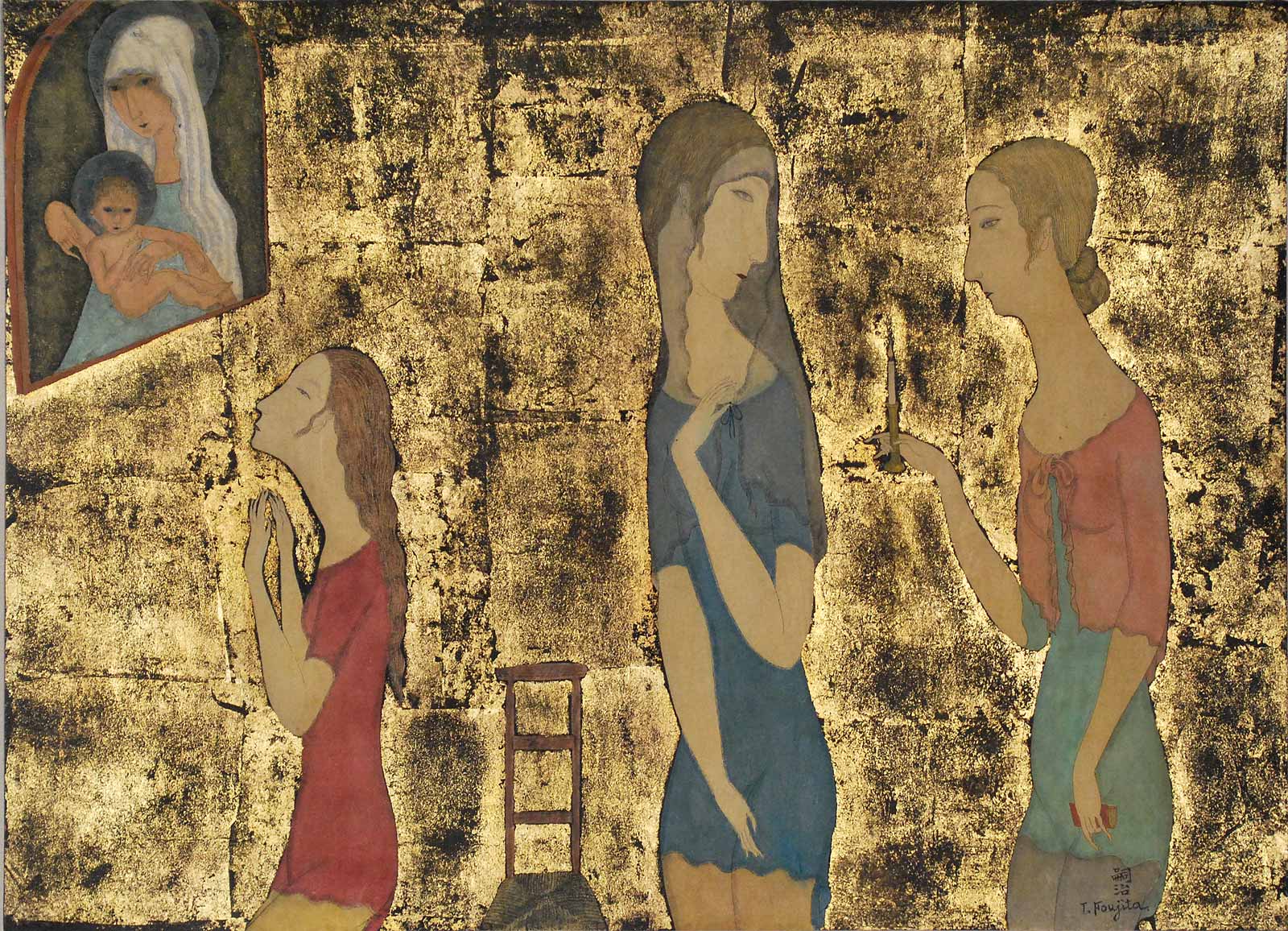

Born in 1886 into an aristocratic military family in Tokyo, Foujita moved to Paris in 1913. At the Louvre, he copied old masterworks, particularly gold-leafed Madonnas. He became close friends with the painters Chaïm Soutine and Amedeo Modigliani. Foujita’s second wife, the artist Fernande Barrey, was one of Modigliani’s models. Among Foujita’s early works, from 1913–1924, are haunting and somber cityscapes of Paris—for example, L’entrée de la cour de l’atelier, 5 rue Delambre (1921). Unlike those of the Nabis or the Fauves, his paintings were drained of color, almost like photographic prints; he attempted neither abstraction nor cubism. It’s one of this exhibition’s fascinating surprises, noted in Anne le Diberder’s catalog essay, that from 1914 onward, Foujita knew the photography of Eugène Atget; by 1920, he possessed copies of both Paysages et documents and La Topographie du vieux Paris.

By the late 1910s, Foujita’s aesthetic had taken one of its many turns. He made a series of ink drawings and watercolors on paper, mostly of women. These borrowed from Japanese composition, with figures that resembled those of Modigliani—perhaps at times too much, such as in La Dégustation (1917), in which two entwined figures share a small carafe and cup. This mixture of European models and Japanese sensibilities is his most consistent stylistic quality in an otherwise varied oeuvre.

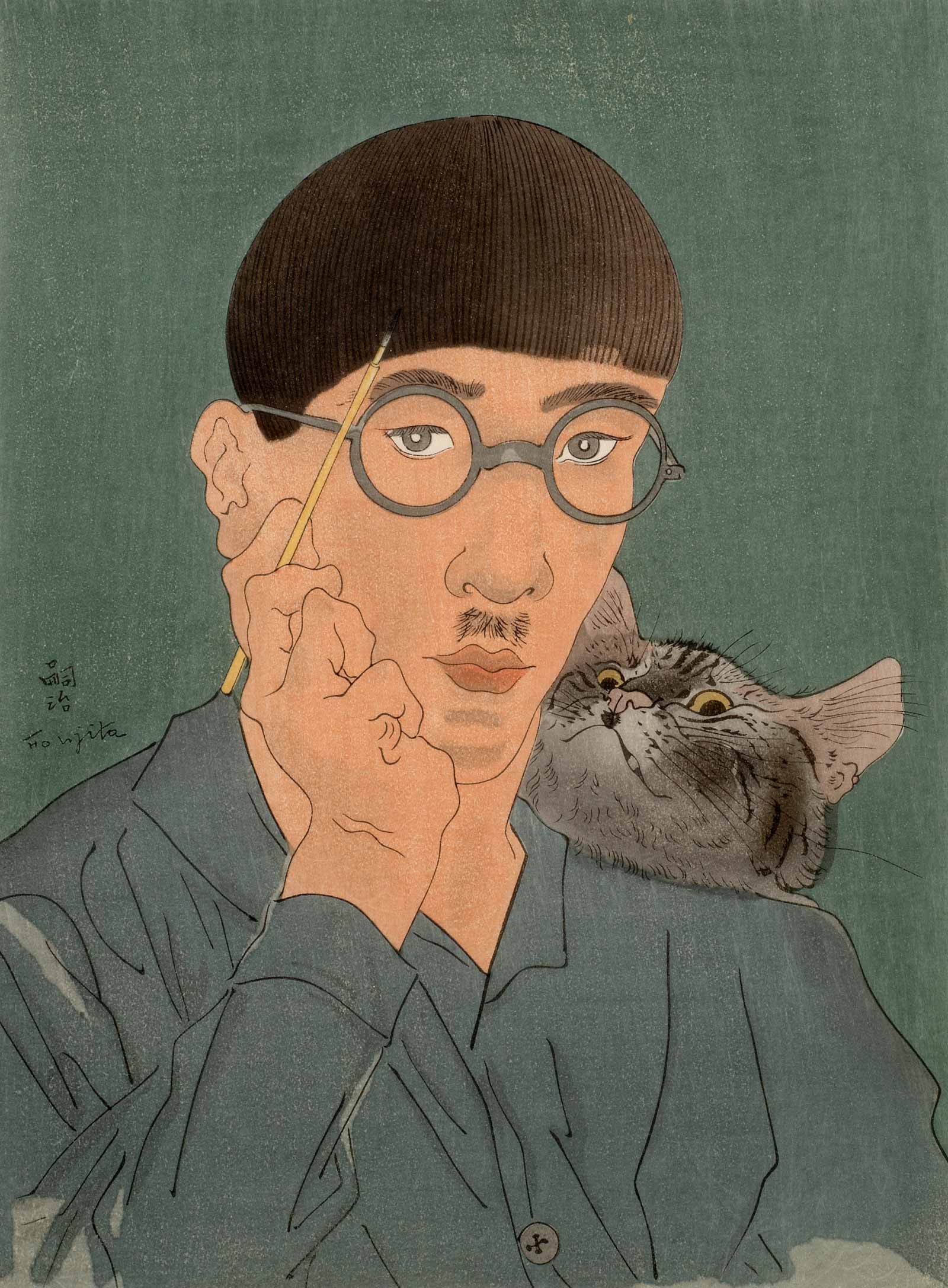

In the 1920s, he found his greatest success with oil paintings and ink and pencil drawings of women, particularly portraits of Youki. While he was celebrated for these works, in retrospect his self-portraiture from that decade is even more captivating. At the Musée Maillol, those vibrant self-portraits, sometimes including cats, are displayed across from photographs of Foujita taken by his friend André Kertész, showing the artist on the telephone, reading, drinking from oversized jugs, or being playful. In photography and self-portraiture, Foujita fashions himself as a character. Perhaps that is why his work still feels alluring and contemporary, although it is sometimes uneven in quality: despite the inconsistent stylistic transformations Foujita himself is constantly present.

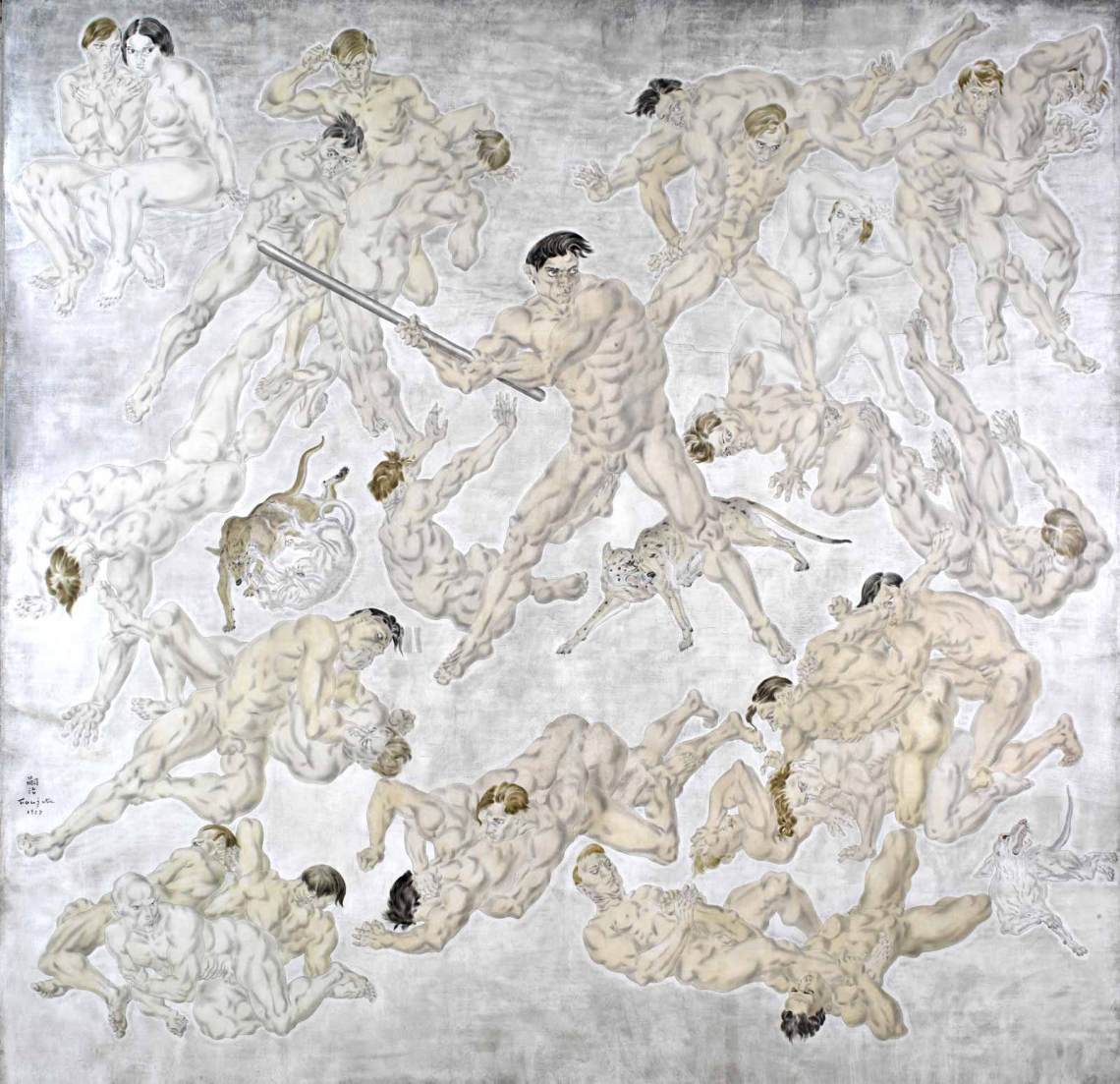

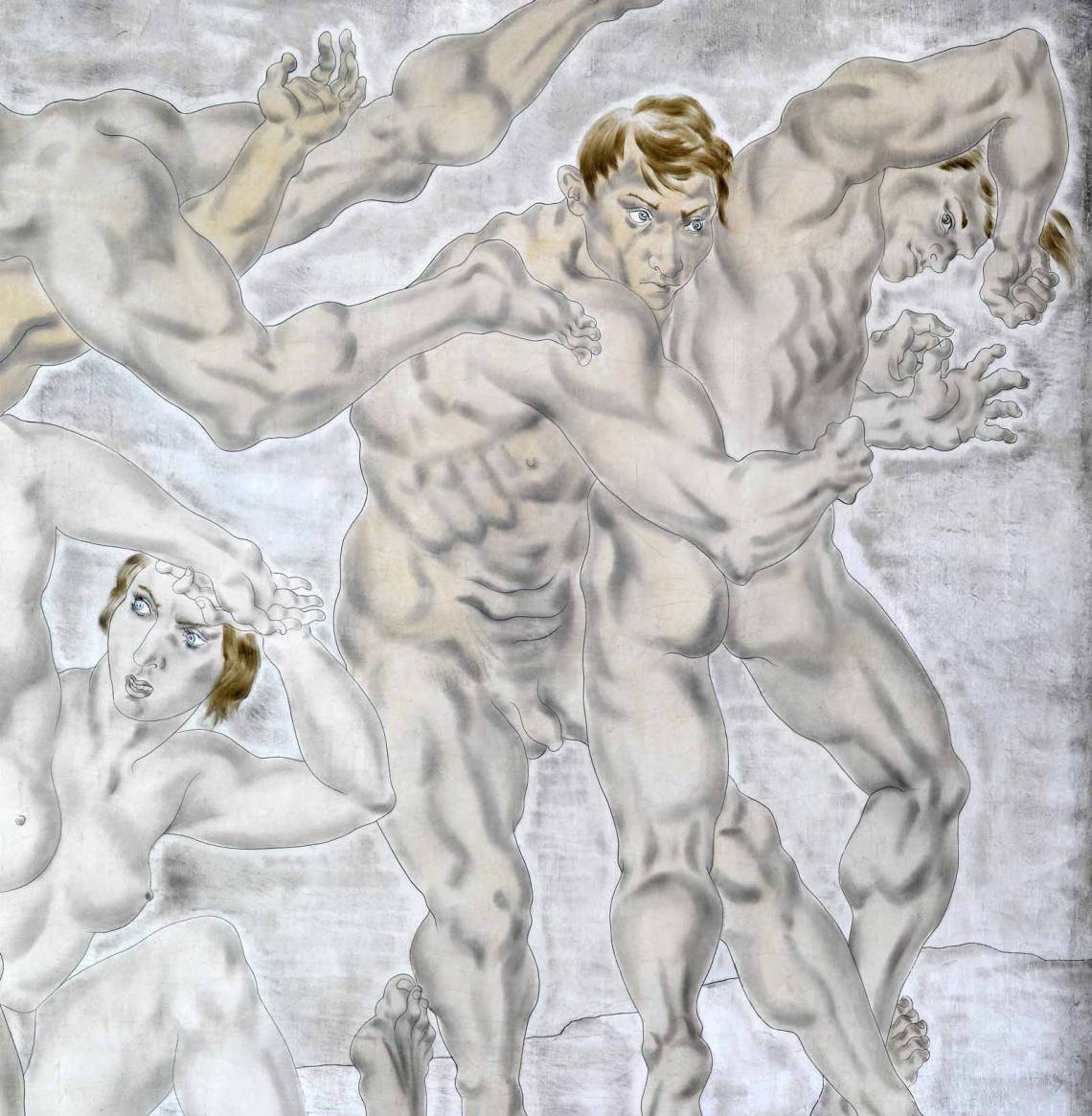

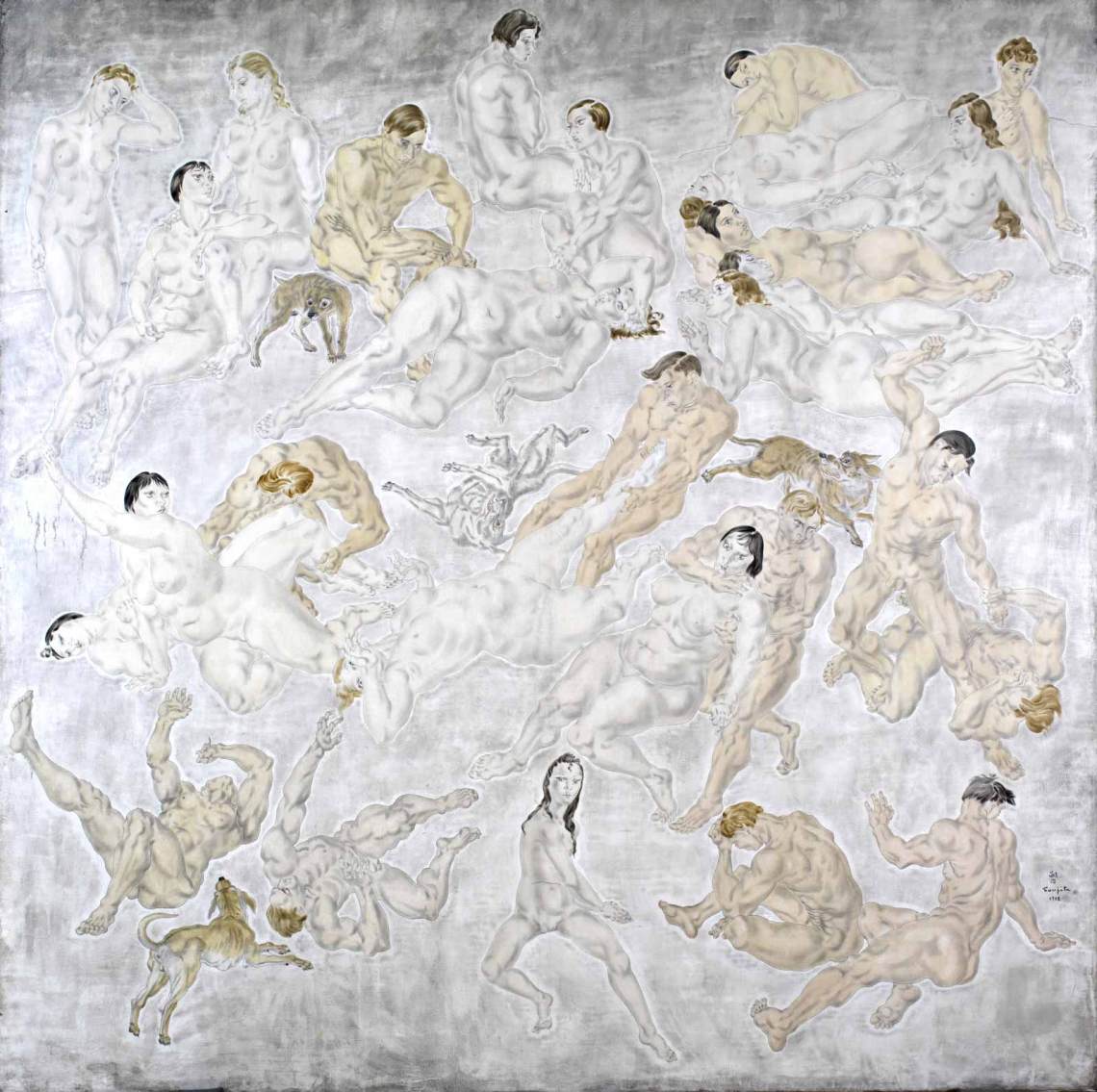

At the height of his popularity, in 1928–1929, Foujita received two commissions in Paris. Grande Composition (1928) is his large-scale, four-panel masterpiece, featuring an arrestingly bizarre menagerie of humans and animals. Its approach merged Michelangelo’s attention to human musculature with lions and tigers in cages, as well as free-roaming dogs and cats, that are reminiscent of classical Chinese and Japanese painting. A year later, the other commission, Décor du Cerle de l’Union interalliée, was a stark contrast to Grande Composition; the exquisite Décor was, instead, a traditional Japanese landscape painting with animals, in a manner that could have come from centuries earlier. While the difference between the two speaks to Foujita’s versatility, it also leaves an impression that he was willing to take on any commission, and execute it in any style.

After leaving France in 1931 and spending years travelling in the Americas, he returned to Japan where he sided with the Empire during its fascist period. In 1950, Foujita emigrated to France because his imperial sympathies made it difficult for him to remain in his homeland after its defeat. Five years later, he was naturalized as a French citizen, converted to Catholicism, and even took the Western name Léonard. It’s ironic that, during that decade, the Fourth and then the Fifth Republics of France were ferreting out their own fascist collaborators (from the wartime period of the Vichy government), and yet welcomed their Japanese prodigal son. He took up residence in Villiers-le-Bâcle, a town southwest of Paris, and focused on religious paintings, particularly the murals of a chapel in Reims, completed in 1966 two years before his death.

One painting included in the exhibition from his wartime years in Japan is particularly poignant. Removed from the modernism of his Montparnasse days, Foujita, sept ans is a realistic self-portrait based on a childhood photograph, a somber-looking image in the sepia-tone colors he applied in his work of the 1910s. It’s hard not to see the painting as rueful, imbued with a longing for the past, although it’s unsure which or what kind of past.

“Foujita: Painting in the Roaring Twenties” is at the Musée Maillol through July 15.