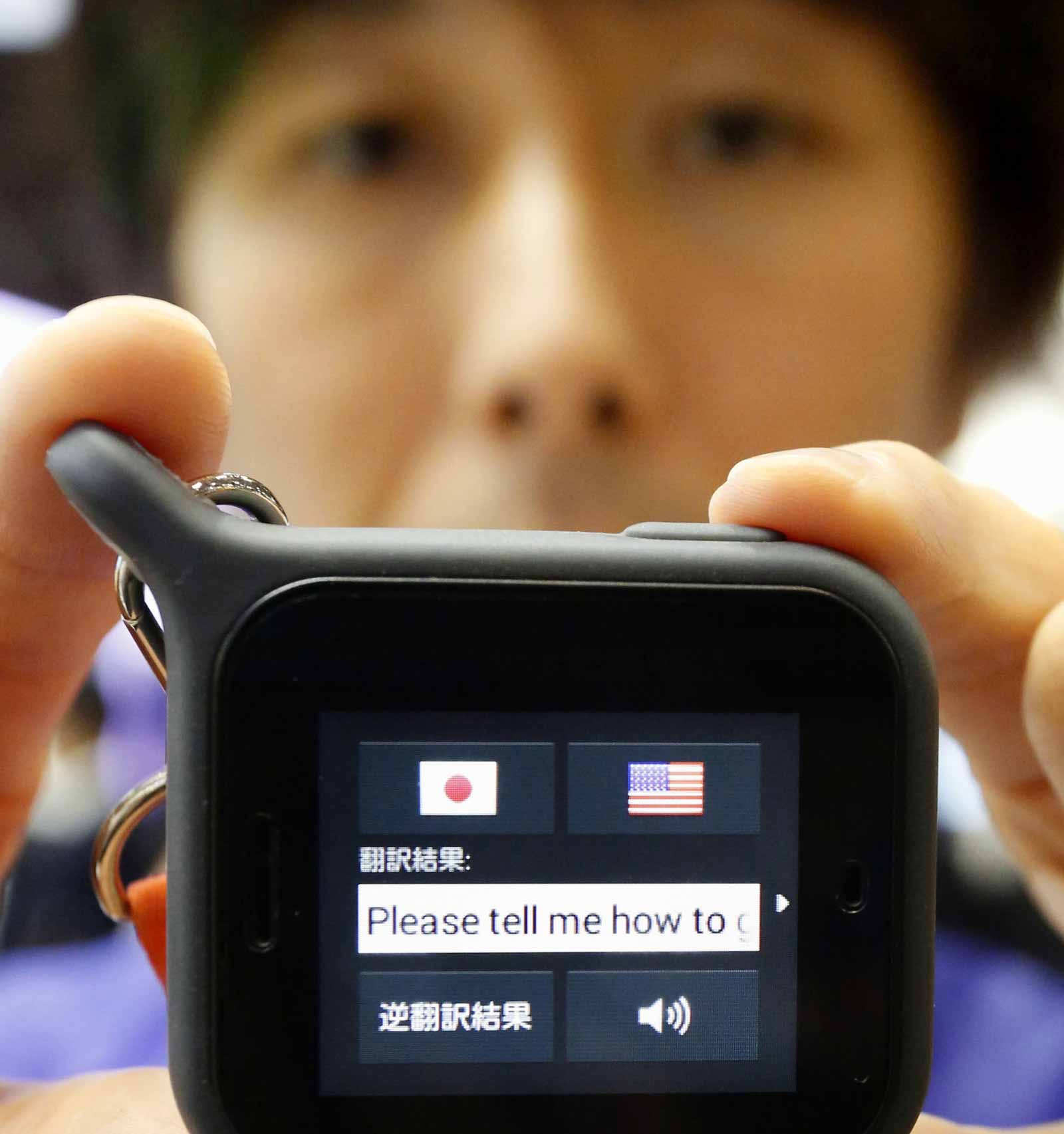

A few days before I left for a trip to Japan with my husband, I signed up to rent a translation device called Pocketalk. According to a press release from January, when the device debuted at the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, Pocketalk “learns as you go, fits in your pocket, and allows for customers to speak in full conversations, not just statements.” (It begins shipping to the United States this month.)

I was looking forward to friendly, meaningful interactions like the one in the Pocketalk promotional video, in which an American man and a girl who is, one assumes, his daughter are window-shopping at a bakery, or maybe a candy store, and are mystified by the goods in the window. The shopkeeper—an older Japanese woman in an apron—appears. “Why is that green?” the girl says, speaking into the small handheld device that is the size and shape of a well-used bar of soap and pointing at something that looks like a small bunch of grapes or verdant donut holes on a stick. Almost immediately, the machine broadcasts a string of Japanese words.

On hearing this, the shopkeeper smiles broadly. She understands! The girl and her father smile back. They understand that she understands! The shopkeeper takes the Pocketalk from the girl and speaks into it in Japanese. “Because they are made with herbs,” we hear the machine say after a bit, and everyone nods as if this makes perfect sense.

“Whether you’re traveling for business or pleasure, being able to speak the local language maximizes the trip,” the CEO of Sourcenext, the company that makes Pocketalk, was quoted in the press release from CES. “It’s like having your own personal interpreter and allows you to confidently travel the world.”

That, in a limited way, is the aim of the Japanese government, which has been pouring billions of yen into the development of artificial intelligence-based translation apps and gadgets in preparation for the 2020 Summer Olympics, hoping they will encourage tourism. “The [internal affairs] ministry wants to provide real-time machine translation services… to help visitors who may feel hesitant about coming to Japan because of the language barrier,” I read in the Japan Times (from a 2015 report). Apparently, they are making progress. A government-funded translation app named VoiceTra that was tested during the Tokyo marathon is now employed by the Japanese patent office. As Eiichiro Sumita, a developer of VoiceTra, told me in an email: “It has made clear recently that AI can improve translation accuracy largely even for the translation between far distant languages.”

I picked up my Pocketalk at the same kiosk in the Narita airport where I was renting a wifi hotspot. I needed the hotspot to use the machine, which relies on an Internet connection to access the databases where artificial intelligence sorts through millions of common words and phrases, looking for ones that best match the ones I spoke into it. It uses those matches to translate what I, or my Japanese counterpart, are saying. That’s the theory, anyway. In practice, as anyone who has used Google Translate knows…

“All bets are off,” I said to my phone using the VoiceTra app when I was still in the US, and asked it to translate my words into Japanese, which it did. But when I checked what the app said I’d said—VoiceTra has a useful reverse translation feature—it wasn’t that at all. Instead, it was a single word: “Sure.” So, all bets were off, though I was still hopeful that a dedicated translation device would do better than an app on my phone.

The funny thing is that once I was in possession of the Pocketalk, I couldn’t make myself use it. Not at the hole-in-the-wall sushi place on our first night in Tokyo, where it felt more natural to point and mime than put a small electronic device between me and the sushi chef. And not at the 7/11 store, trying to figure out which bottled green tea was sweetened and which was not as customers queued behind me, eager to pay for their takeout jam-pan meals and cigarettes and get out of there. And not in the hotel. And not at the train station. And not in the taxi. And not at the ramen shop. I could go on.

Finally, as I was walking through Yoyogi Park in Tokyo one morning, I saw a woman and an Akita standing beside a poster that seemed to indicate that the dog did some kind of therapy work. I was too curious not to stop. I turned on the Pocketalk and said, “Beautiful dog.” I wanted to ask if I could pet the dog, but the device hadn’t yet translated “beautiful dog,” and I didn’t want to confuse it. “We have to speak to the machine concisely and targeting the microphone precisely,” Eiichiro Sumita had cautioned me in his email. “If you don’t do that, the speech recognizer takes a long time and returns erroneous results and translator generates crazy sentences.” Eventually, “beautiful dog”—or possibly something else—came out of the device in Japanese, so I tried to pass the Pocketalk to the woman just as in the promo video. She looked at it, and me, skeptically, and did not take it. She did say something, though it was probably not, as the Pocketalk announced, “special king dog.”

Advertisement

One reason Japanese is a difficult language to translate, Sumita told me, is that “people often omit subjects because Japanese people understand each other without mentioning subjects.” In this case, I think we were both clear that the subject was the dog, which sat there patiently and unconcerned. No doubt, it was well-acquainted with the problems of translation. As I turned to leave, a woman standing nearby spoke up. “This is a specially-trained hearing-aid dog,” she said in perfect, British-inflected English. “They are here to raise public awareness.” I thanked her and put the Pocketalk away. It was days before I took it out again.

“Why are you wearing a rubber Donald Trump mask?” I asked a Japanese man two rows behind me at an amphitheater in Kyoto. A band was playing on stage, and people were coming and going, and this man was standing up in the back, impersonating Donald Trump, or making fun of Donald Trump, or channeling Donald Trump—it wasn’t clear which. I wanted to know, and so (I think) I asked him. I did not preface my question with any sort of introduction. I just walked up to him, spoke into the Pocketalk, asked the question, and waited. And waited. Lag time is an issue with translation apps and devices.

“If people use the AI translator correctly, it returns translation in fairly short time without disturbing conversation,” Sumita told me. But fairly short is subjective. Seconds—fifteen seconds, twenty-five seconds—can stretch out uncomfortably when you have approached a stranger, spoken a foreign language into a little black gadget in your hand, and are waiting for it to reveal why you are standing there. No words emerged. Maybe it was too noisy, maybe there were no matches to the words “rubber Donald Trump mask.” The man shooed me away, gesturing in the universal language for me to get lost. I guess my finger must have been on the Japanese-to-English button as I retreated to my seat, because suddenly, unbidden, the Pocketalk spoke. “The dream of the right is Ginza,” it said. (Ginza is a wealthy enclave in Tokyo.)

Not long after that, my husband got a blister on his foot and lanced it with an unsterilized needle from one of those sewing kits you sometimes find in hotel bathrooms. After lecturing him on the dangers of MRSA, I took off for the pharmacy, Pocketalk in hand, in search of something like Neosporin. Medical emergencies—of which this was not one yet—were one reason the Japanese government was funding translation apps and devices. According to that 2015 Japan Times article, it was planning on installing AI-based translation services in hospitals.

“Do you have antibacterial ointment?” I said to the Pocketalk, then aimed the device at the young man behind the cash register. Some words came out of the machine. The clerk looked confused. I tried again. Actually, I asked the same question, the same way, three times and each time got the same response. (For the record, that is not how machine-learning works.) It occurred to me that my words were too precise, so I switched them up. “Do you have medicine for a cut?” I asked. “Cut,” the clerk said in English, bypassing the device. “Cut,” I repeated. “Ah,” he said, and led me to a mouthwash display.

Back in Tokyo, we made a pilgrimage to Akihabara, the epicenter of Japan’s tech world. We muscled our way through the crush of young people swarming in and out of electronics and manga stores, to look at the latest versions of talking toasters and AI-enhanced televisions and robotic coffee-makers. Here was one version of the future, where everything at home, and at work, and in your life more generally will be controlled off-site, somewhere, by something. This future was sleek and well-designed—and why not lie down in a bed that knows your sleep habits better than you do? Why not travel the world speaking into a machine that beams your words up to the cloud and beams them down again using chunks of other people’s conversations?

Advertisement

On the hectic fourth floor of the famous Radio Kaikan complex, I followed some signs that led to a desk where a young man stood with a cardboard sign hung around his neck: “I use a voicecast machine and can talk in English,” it said, next to a picture of the Pocketalk. I took out my machine to show him I had one, too; I was eager to have, at last, a real conversation with someone who understood how this exchange was supposed to go. So many questions formed in my mind. Was the manga department, with its floor-to-ceiling comic books, trading cards, and posters, always so crowded? Why was everyone there male? How popular were domestic robots? Were talking toasters multilingual? Could he recommend a good yakitori restaurant in the neighborhood?

But I decided to start by asking him about the machine. “I would like to talk with you about your Pocketalk,” I said. Mine had run out of power, so I spoke into his. Words came out in Japanese, but either they were too faint to be heard above the din or they made no sense, and he shrugged. “How do you like this translation machine?” I tried. Nothing. “Does this thing work pretty well?” I asked. He finally seemed to understand what I was getting at, and spoke quickly into the device.

“I have no information about that,” he said.