At the Di Donna Galleries on Madison Avenue, the masks of the Yup’ik, an indigenous people related to the Inuit, seem to float off the dark blue walls where they hang, between paintings by Yves Tanguy and André Masson, Joan Miró and Enrico Donati, Victor Brauner and Wolfgang Paalen—all Surrealists, most of whom fled wartime Europe in the 1940s for New York. The connection between the Surrealists’ productions and the Yup’ik artefacts in the installation is never direct: they seem, rather, to have drifted together naturally.

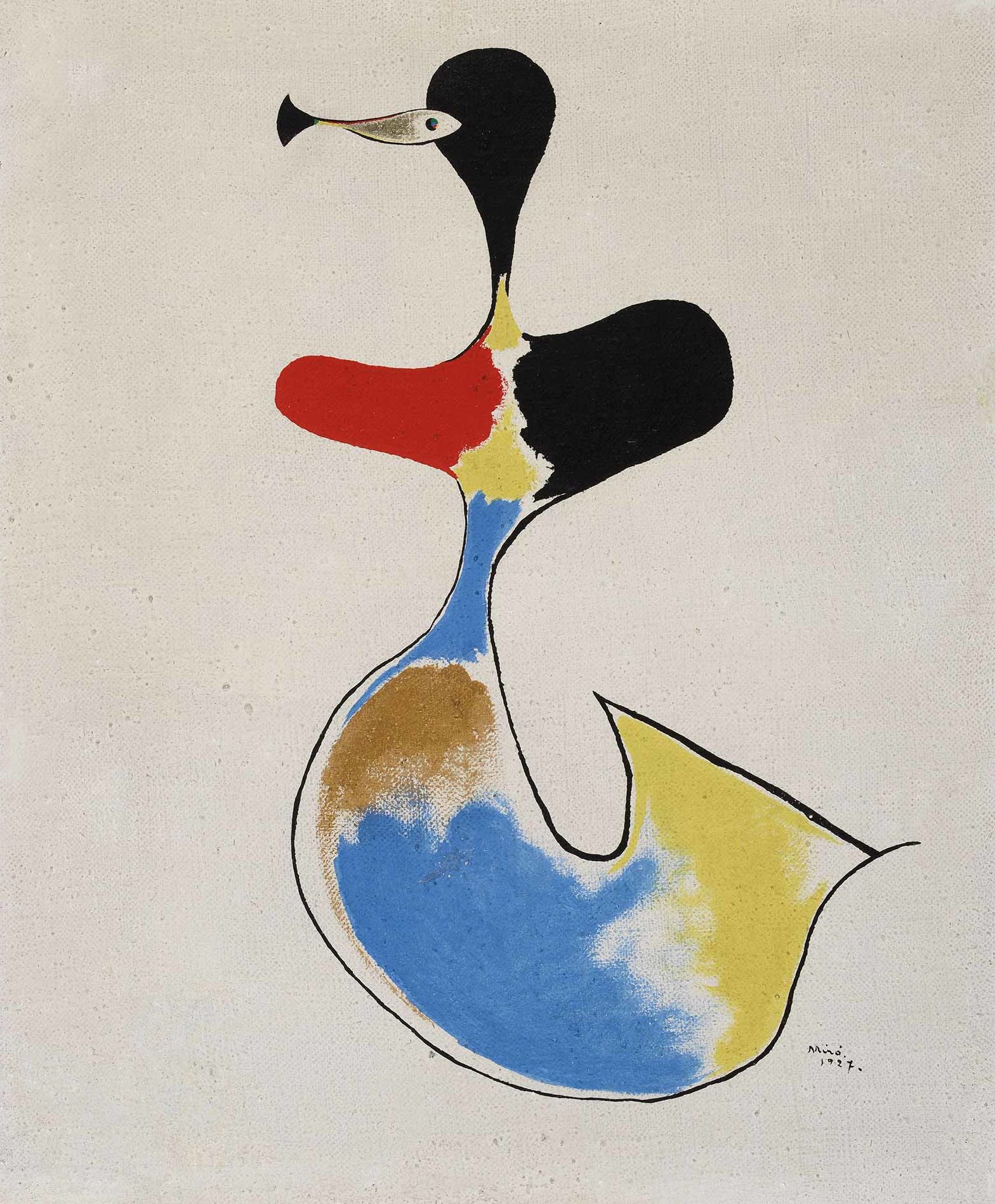

The first mask on entering, from Goodnews Bay, Alaska, which once belonged to André Breton, has one round eye, carved out, and one slanted, like an almond set at an angle. The nostrils are lopsided; one is graced by whiskers, the other by a kind of eyebrow. A little wooden fish is poised to jump into the mask’s mouth. Hands emerge from its temples. Nearby is a painting by Joan Miró—Peinture, (La Sirène) (1927)—in which a flowing curvy figure consists of splotches of color, suggesting an arm or the tail of a siren, with a little fish poised over its face.

The masks are made of driftwood, from villages placed at the mouths of enormous rivers—the Yukon and Kuskokwim—in an arctic landscape with no trees. Spring flooding brought down large trunks, mostly cedar and fir, from the interior. “The mask was put on the dancer,” said Donald Ellis, who co-curated the show with Emmanuel Di Donna, “and as the dancer began to sing and dance, it was activated and became a conduit between the physical and the spiritual world.” The masks often have arms and hands, but never thumbs, so that the conduit would not be able to hold back the spirit summoned by the mask and traveling outward into the world. Many of the masks have a plate on the inside for the dancer to bite so that the mask would appear to float in front of the face. In fact, the Yup’ik term for mask translates to “face in front of the face,” or floating face. It took extraordinary skill to dance with a large mask held between the teeth. The ceremonial dances took place in the qasgiq, or “communal men’s house”—darkened spaces lit by whale-oil lamps in shallow stone bowls.

André Breton and Man Ray had first seen Yup’ik masks in 1935 in Paris at the Galerie Charles Ratton in Paris. But it was Max Ernst who introduced his friends to a trove of them in Manhattan. He was walking down Third Avenue one day when he spotted a spoon from the Northwest Coast in the window of Julius Carlebach’s antiques shop. Ernst’s wife, the painter Dorothea Tanning, told the story: Ernst went in to ask about the spoon and, when he discovered that it was part of a collection of spoons, bought them all from Carlebach. At the time, the Heye Foundation, which had opened the Museum of the American Indian, at Broadway and 155th Street in Washington Heights, in 1922 (now part of the Smithsonian Institution), was having financial difficulties and had decided to deaccession a group of beautiful Yup’ik masks. The masks were sometimes made in multiples, for the multiple participants in ceremonial dances, and George Gustav Heye had collected them that way. Twenty years later, the curatorial staff decided they didn’t need to keep more than one of each.

A man called A.H. Twitchell, an amateur ethnologist with a trading post on the Kuskokwim River in Alaska, had originally acquired many of those masks, and among those who collected them he was the one of the few who had thought of recording the names of the masks and their meaning. He had sold some fifty-five of them to Heye. Out of these, about half were deaccessioned in the 1940s through Carlebach, and almost all, thanks to Ernst’s discovery of his antiques store, went to Surrealists.

The Surrealist painter Enrico Donati recalled that they would pile into a convertible with what he called “a box of beer”—Man Ray, Ernst, Carlebach, and Donati himself—and go up to a warehouse in the Bronx where the pieces were kept. According to Ellis, the Donati family has a photograph by Man Ray of Carlebach, Donati, and Ernst in authentic Indian costumes from the warehouse. Donati slept beneath one of the masks and kept another at his studio. Like Breton, who adopted Donati into the Surrealist circle when they met in New York City, Donati believed it acted on his psyche through his dreams. Also devoted to collecting these artefacts were the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, and the artists Roberto Matta, Georges Duthuit, Isabelle Waldberg, and Robert Lebel, who made some stylized drawings of the masks. Collecting, according to Marie Mauzé in her catalogue essay, “The Yup’ik World and the Surrealists,” was a “means of combating feelings of isolation… for exiles who felt uneasy in North America.”

Advertisement

Freud had opened the way to thinking about the irrational. But just as Picasso’s “primitivism” wasn’t merely esthetic—primitivist objects seemed to contain a kind of power that was renewing all of Western representation—so, too, the Surrealists, like the Renaissance art historian Aby Warburg in his personal immersion in the Serpent rituals of the South-Western Pueblos, were keenly interested in a contact with a spirituality that did not shy away from the mysteries of physical life—through dreams, rituals, trances, magical and religious thinking—or from the paranormal intuitions of schizophrenics. They were drawn to all the ways that conscience might be transformed, and so in shamanism and the taking on of different identities, such as those of animals, through rituals that enacted these identifications with the realm of the dead and of the non-human, or in forms bordering on paranoia. Claude Lévi-Strauss was still young but anthropology, notably in the writings of his master Marcel Mauss, as well as Georges Bataille and Michel Leiris, was clearly the new philosophical discipline. This is how the Surrealist painter Leonora Carrington, living in Mexico City in her eighties, told me she saw the kindly woman who took care of her infirm husband: “I feel as though I were on a raft being pursued by a crocodile and that I must throw bits of food at it so it won’t eat me.” She was appeasing a dangerous beast. The Yup’ik danced as an offering and an entreaty to the animals they would hunt.

Ellis began to collect Native American art when he was seven, and started tracking down Yup’ik artefacts in the hands of Surrealists, or their heirs, thirty years ago. In the process, he found a lifelong friend in Donati, who lived to be ninety-nine and told him more than once, “Donald, the minute they shut the door on the hearse, the masks are yours!”

One of those very masks was the South Wind or Complex Mask, of which Ellis said:

The Yup’ik lived in the harshest conditions. Everybody would have been touched by starvation at some point. If they failed to catch a whale in season they would have a very difficult winter. The long thin sticks represent rain, and the wind is represented by the tube. The Yup’ik danced to appease animal spirits. In the dance they summoned the south wind because when the wind moved from north to south it meant the coming of spring, when the ice broke and the whales returned.

Donati apparently believed that his South Wind mask watched him work. It surprised him, when he visited younger painters’ studios in Brooklyn, to see nothing but canvas and paint, so different from the Surrealists’ studios, which were like wunderkammer, with fossils and rocks, and tribal arts—“objects of inspiration,” as Donati called them. “It’s not so much about the way that the artists looked at the masks, but about the way the masks looked at the paintings,” Ellis says.

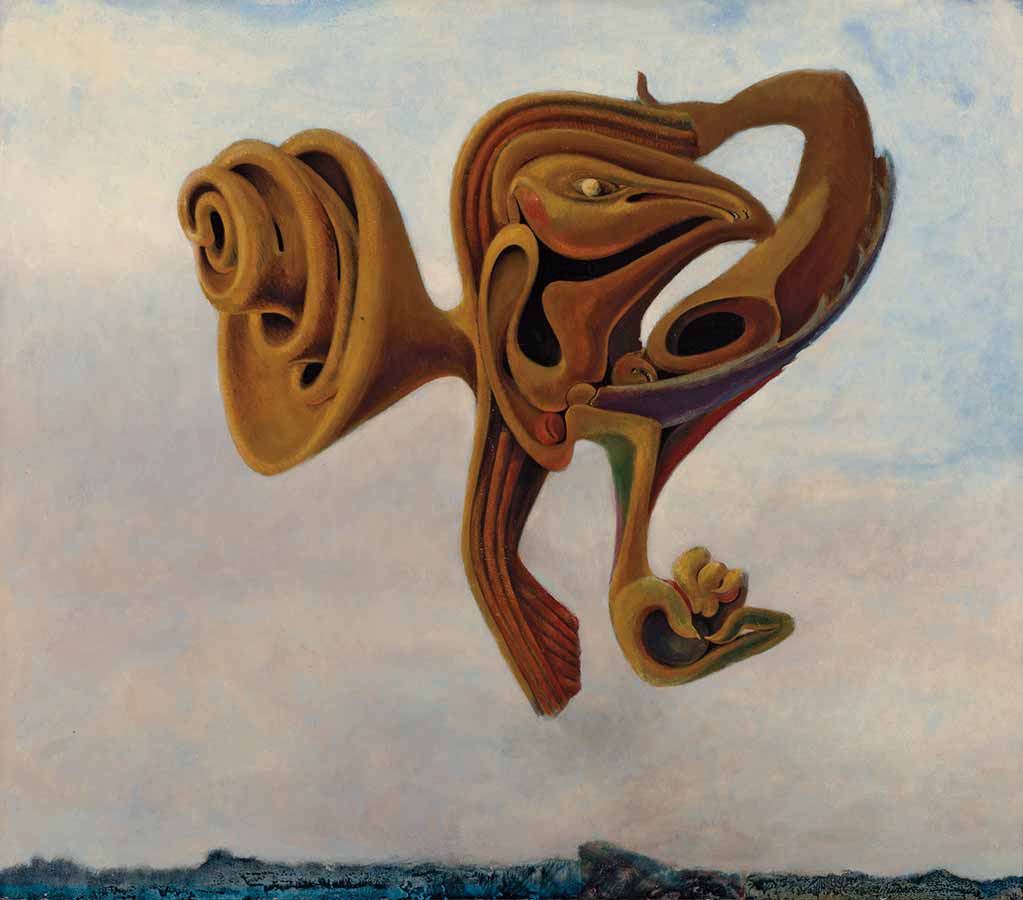

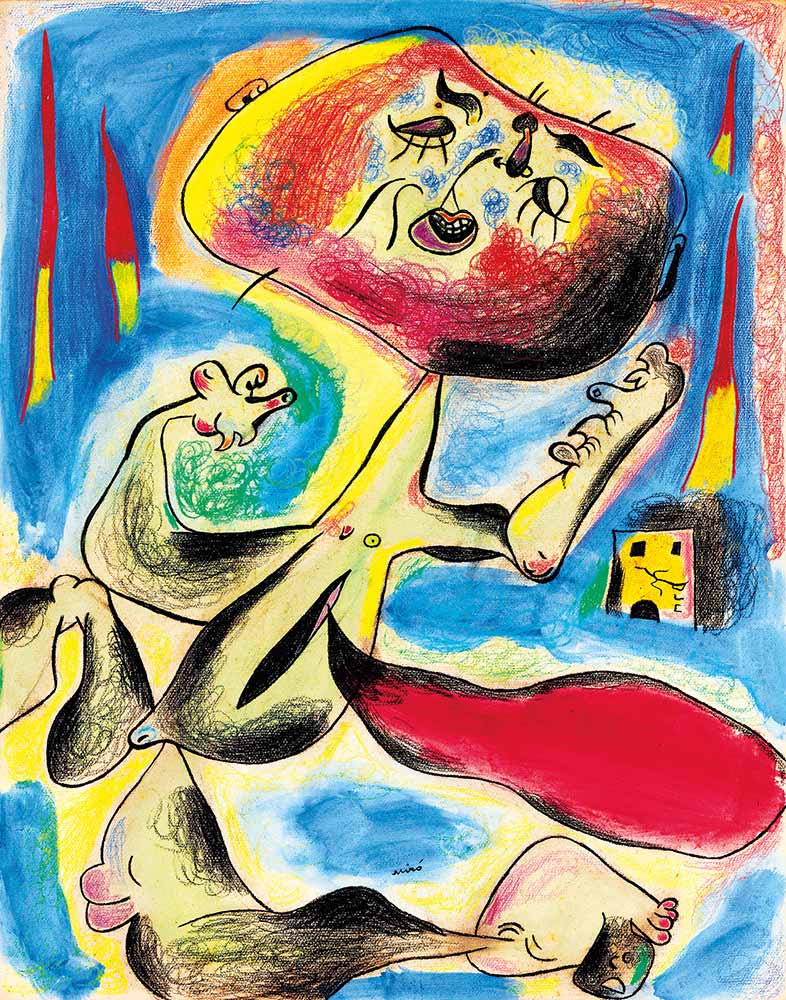

Miró’s Tête et oiseau, conceived in 1981, and one of the largest sculptures in the show, rests on two rough wooden blocks. A dry pumpkin shell with a long, bent nose, and no other facial features, affixed to a tall wooden plank, is a mask-like presence. Max Ernst’s bronze sculpture Petit Génie de la Bastille (1961) is a little black figure with outstretched fin-like arms, the top of the head squared like a paper bag turned upside down. The mouth is set in a pout. Ernst’s painting Une Oreille Prêtée (1935) is one the painter George Condo must have seen, at least in a dream. It is a flesh-and-caramel-colored flying composition (an ear, perhaps, as the title suggests), with something resembling a bird’s head embedded in it. It hangs next to a droll late-nineteenth-century mask with a bent protruding beak. But the most assertive mask has two foot-long stick-like arms proceeding diagonally from its chin and a pole rising from its forehead ending in a bird’s head with a feather on its crest. Some Mirós, such as Personnage or Femme en révolte (1938), a large gouache and charcoal on paper, just look perfect in the mix—the expressive pumpkin face is in keeping with the Yup’ik style though only in a subterranean way.

Advertisement

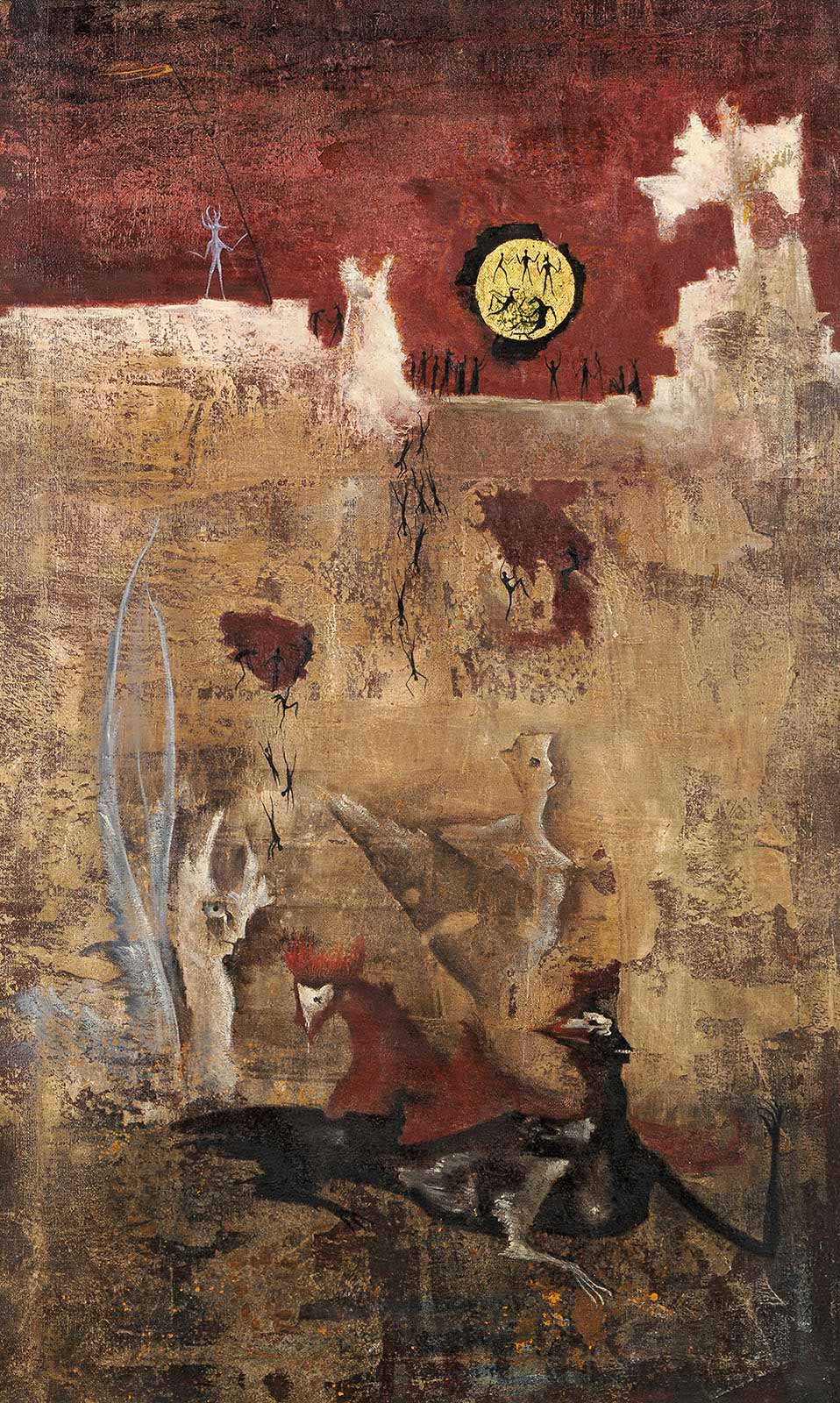

In a disquieting picture by Leonora Carrington, Composition, Ur of the Chaldees (1950), slender black figurines topple down from a golden moon into a coppery cracked abyss where large white, red, and black creatures, including a sphinx-like figure with a large eye in profile, appear to await them. Most of Carrington’s paintings of this period and just after appeared in a 1947 show organized by Edward James (builder of Las Posas, a garden of concrete follies in Xilitla, Mexico) at the Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York, and have rarely been seen since. (Carrington had lived with Ernst for three years in the late 1930s in Saint-Martin-d’Ardèche, before he was imprisoned as a “hostile alien” and she had a nervous breakdown and was committed to an insane asylum, of which she wrote an admirable account in Down Below.)

Another of Ernst’s sculptures—a tall column of burnished bronze with a moon face and googly-eyes—reigns over all. But off to the side are two extraordinary black-and-white photographs taken by Kati Horna, one from the series Oda a la necrofilia (1962), the other a portrait of Remedios Varo, a Surrealist who was originally from Spain, wearing a shrew-snouted, wild-eyed mask made by Leonora Carrington. The three artists were great friends in Mexico City. Nearby in a glass case is a sticklike wooden figure by Carrington, Lepidóptero (circa 1952), that seems to have just landed from a 1950s science-fiction outer space. This is the moon dancer, the Surrealist soul incarnated in a mask figure.

A bright yellow, red, and black Alexander Calder painting of a face has eyes that spiral into a nose. According to Emmanuel Di Donna, André Masson lived in Calder’s studio for a time when he came to the US as a refugee during World War II. The Painted Mask by Man Ray (1950s), with dark brown shadows on its heavy lids and lips tinted pink, has a dark triangle on its forehead, just like that on the Mask of a Valley Ptarmigan nearby.

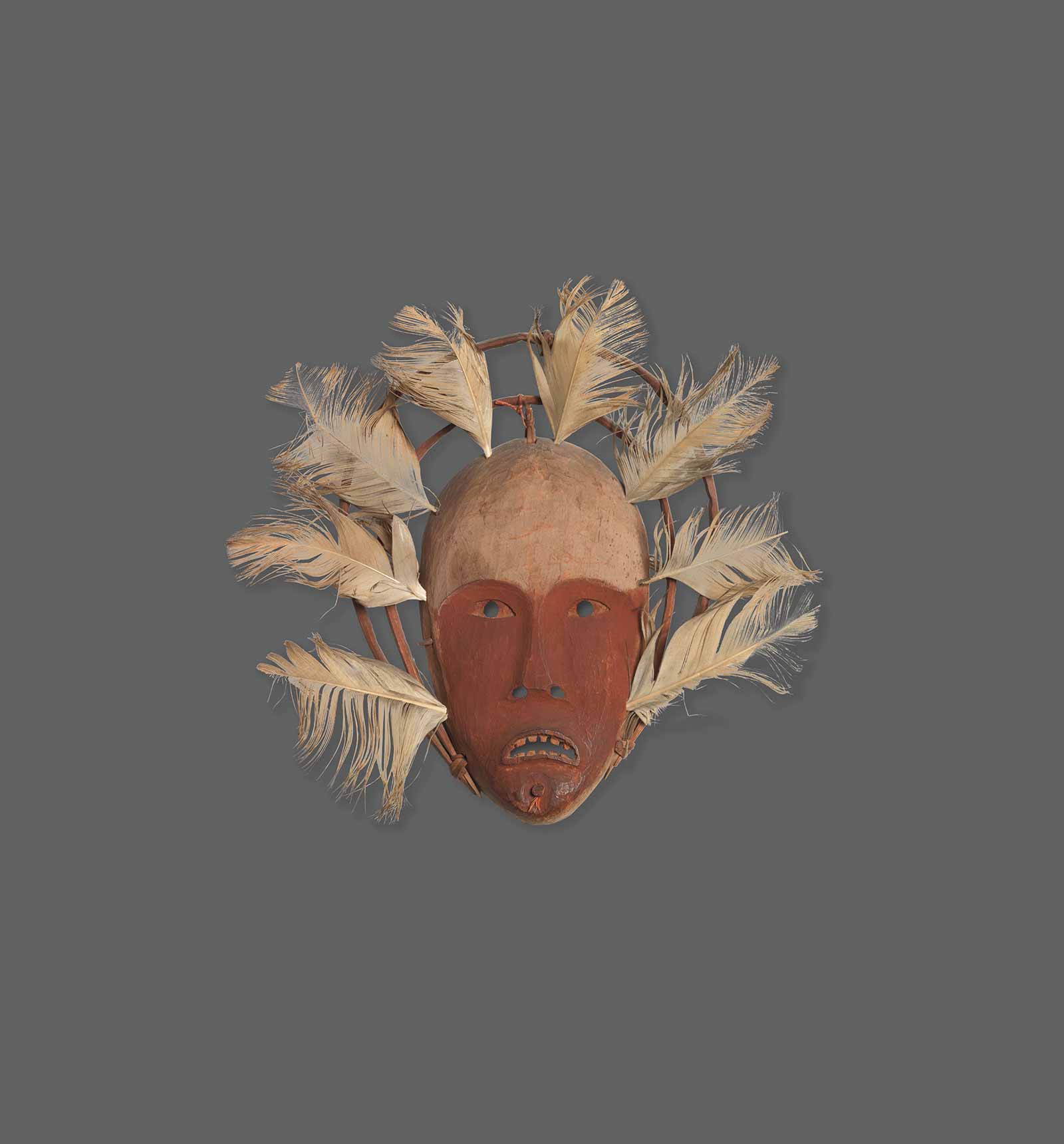

A smaller and more delicate wooden mask with a stunned look, the perfect oval of its face surrounded by eight feathers, was once in the collection of André Breton. Next to it is Breton’s Madame… Poème-objet (1937), an assemblage with a sinewy white furry animal no longer than an index finger descending into the composition above three little metal stars. “Quelle tempête cette nuit,” Breton wrote next to it. “Small, apparently insignificant creatures could act as helping spirits,” according to one Yup’ik, Mary Mike. Breton believed in the superiority of animals and “invisible beings,” such as spirits, and in the power of objects over humans.

An earlier version of this essay misidentified Remedios Varo as a Mexican Surrealist; she arrived in Mexico in 1941, and while she remained in Mexico until she died in 1963, she never became a Mexican citizen.

“Moon Dancers: Yup’ik Masks and the Surrealists” is at the Di Donna Galleries through June 29.