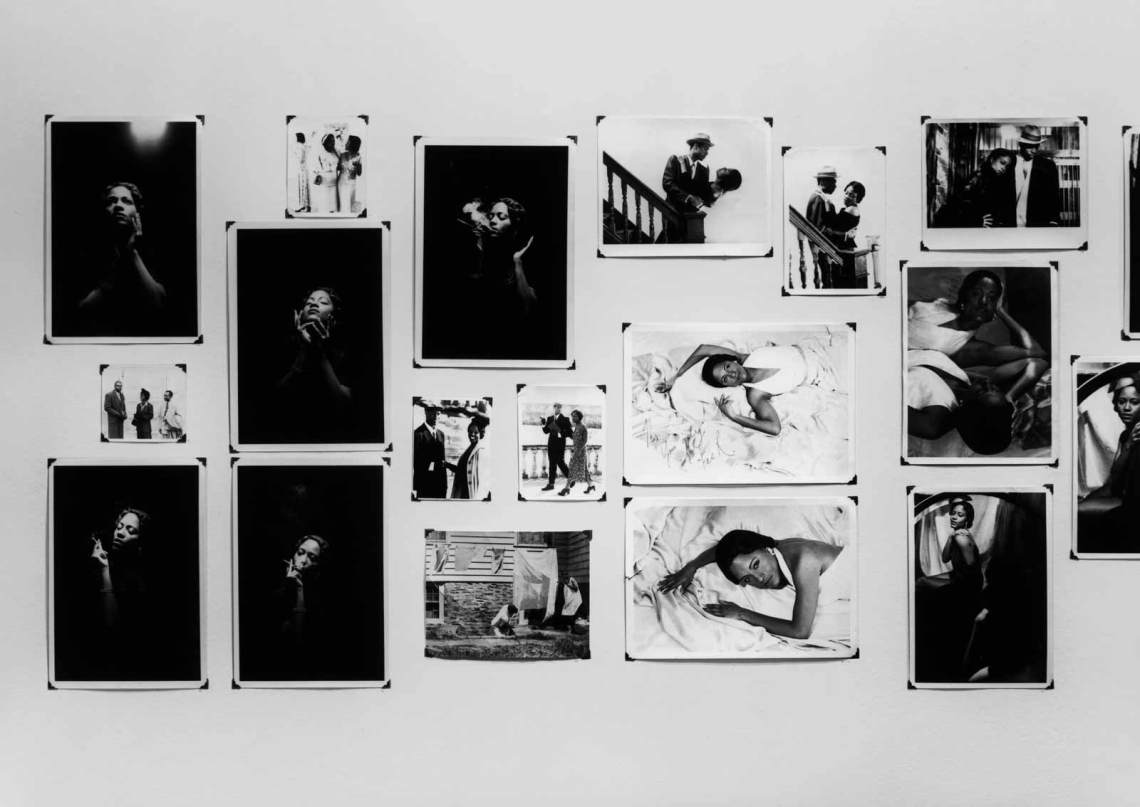

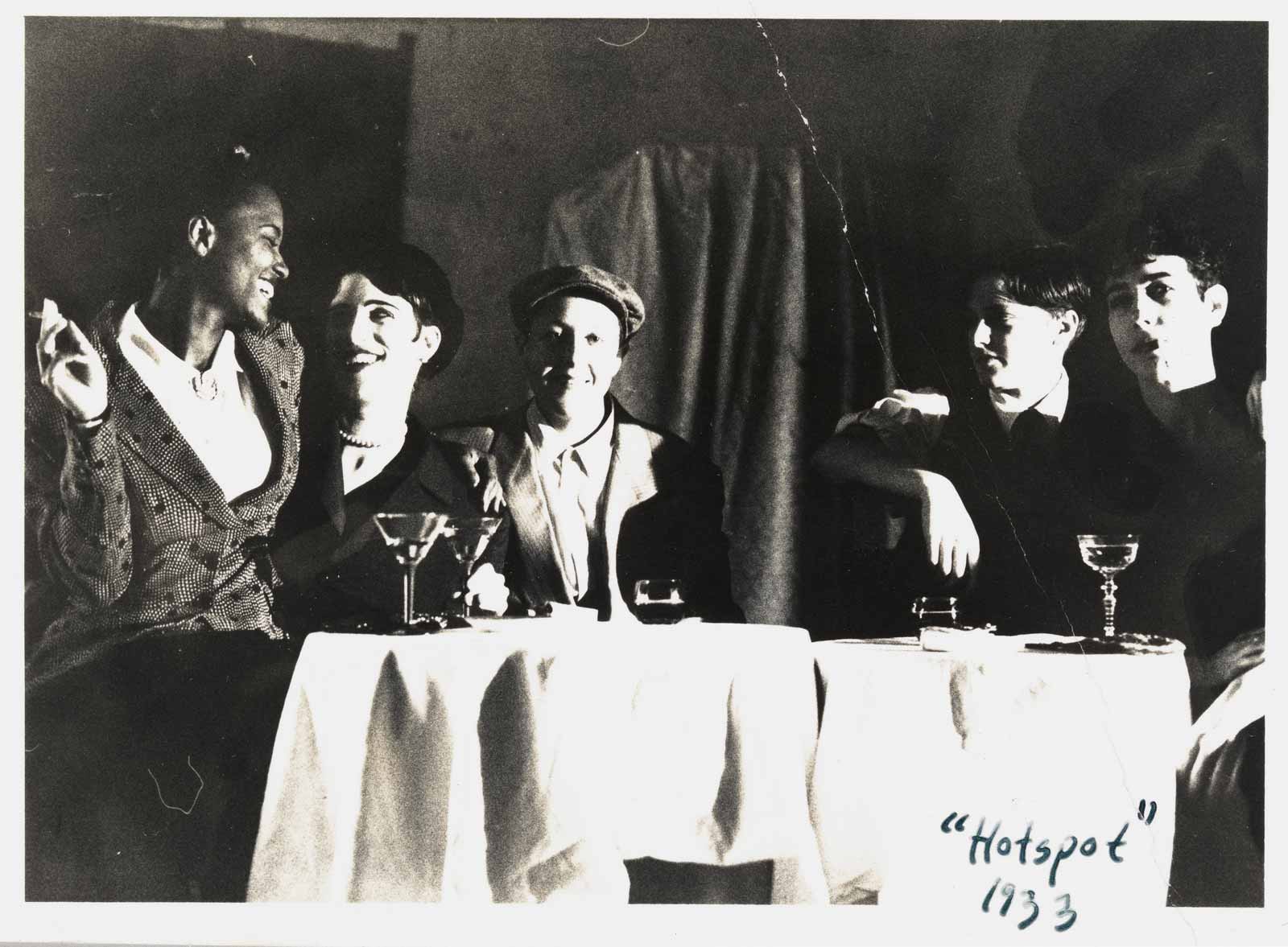

In The Fae Richards Photo Archive, one of the works in Zoe Leonard’s career-spanning show “Survey” now at the Whitney Museum, a viewer can trace the contours of a daring, unusual life. In a series of photographs, Richards, a black lesbian actress working in 1930s Hollywood, can be seen costumed in promotional shots for her films. She brings feeling and intelligence to roles associated with racist stereotypes—the disapproving maid in a ruffled apron in one comedy, an enslaved woman on her knees praying to God in a Confederate-nostalgia film called Plantation Memories. In other promotional photos, we see Richards made up and dramatically lit, cigarette smoke curling around her lips—these are from her early career, when she performed as a lounge singer. But the shots from Richards’s private life tell the story of who she really was. She sits perched on the lap of a lanky white butch lover—a film director—grinning and holding a coupe glass of champagne. She stands in a sunny field in the country, a friend’s terrier asleep at her feet.

Leonard has put the photos—gelatin silver prints, chromogenic prints—in rough chronological order, so we can see the progress of Richards’s life: how she left show business and eventually settled into a quiet existence in her native Philly, partnered with a woman who stays with her until her death. The images are so thoughtfully arranged that it feels like a work of love, like pictures assembled for a wake. It is jarring to realize, from a plaque on an adjacent wall, that Fae Richards was a fictional character, who appeared in The Watermelon Woman, a 1996 film by Leonard’s friend Cheryl Dunye. Dunye commissioned Leonard to create the character, who is pictured in faux-archival images shot in pre-production. But the photographs are beguiling because they are marked with the attentiveness and verisimilitude that characterizes so much of Leonard’s work. Like other items in the retrospective, it is an effort to reconstruct and memorialize a past that’s been lost—to homophobia, repression, hatred, short-sightedness, or carelessness. Richards didn’t exist, but Leonard constructs her as an homage to the black, gay women who did.

Leonard, who works primarily in photography and sculpture, was born in 1961 in a small town in upstate New York. She dropped out of high school and moved to the city, finding a community amid the booming East Village arts scene of the late 1970s and 1980s. She lived her formative years there, among other gay people, committed leftists, and others who saw the world with more sensitivity and political vigilance. But Leonard’s world was soon to be devastated—first by the AIDS crisis, which killed many of her friends, then by the gentrification that displaced others.

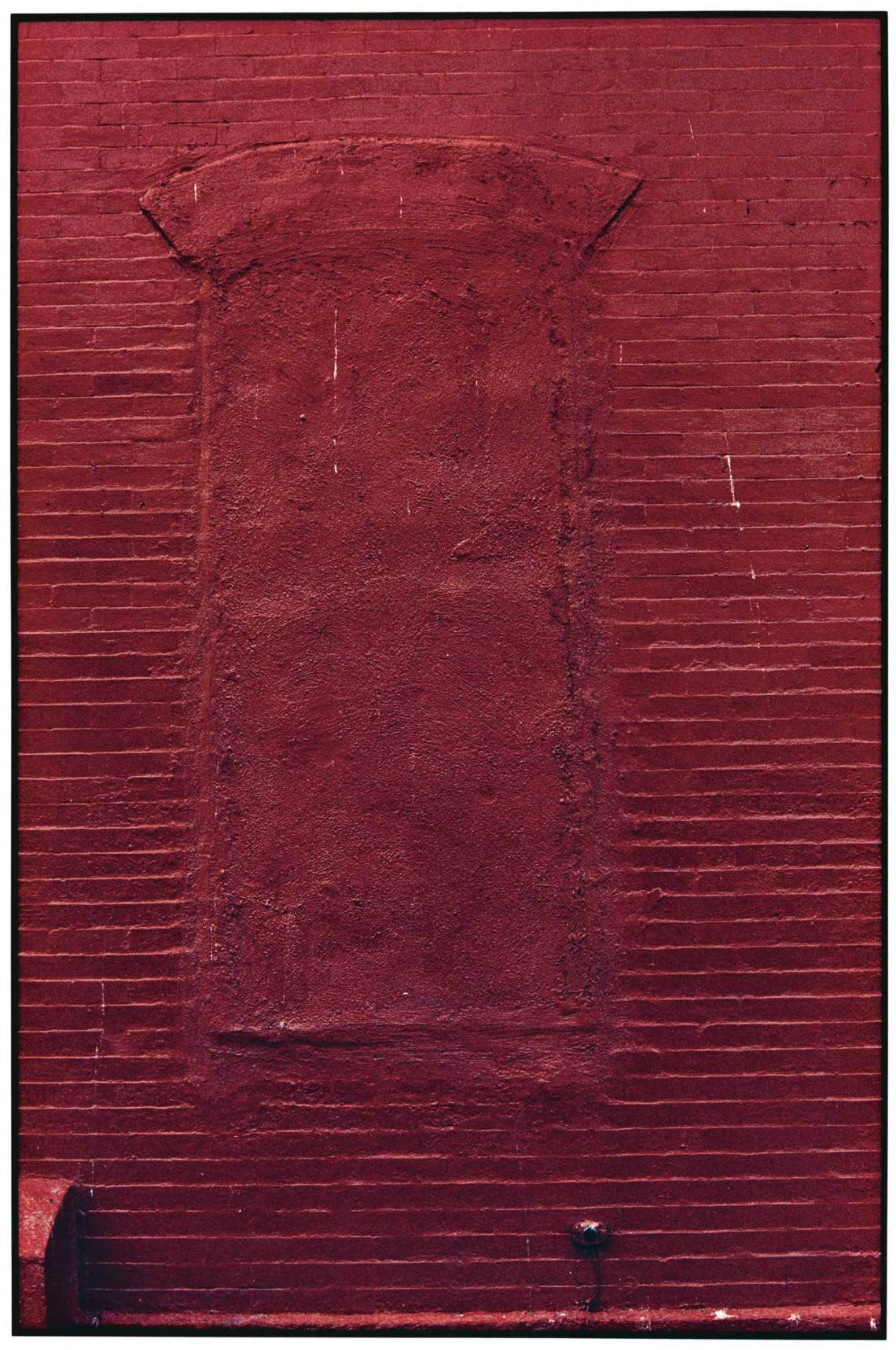

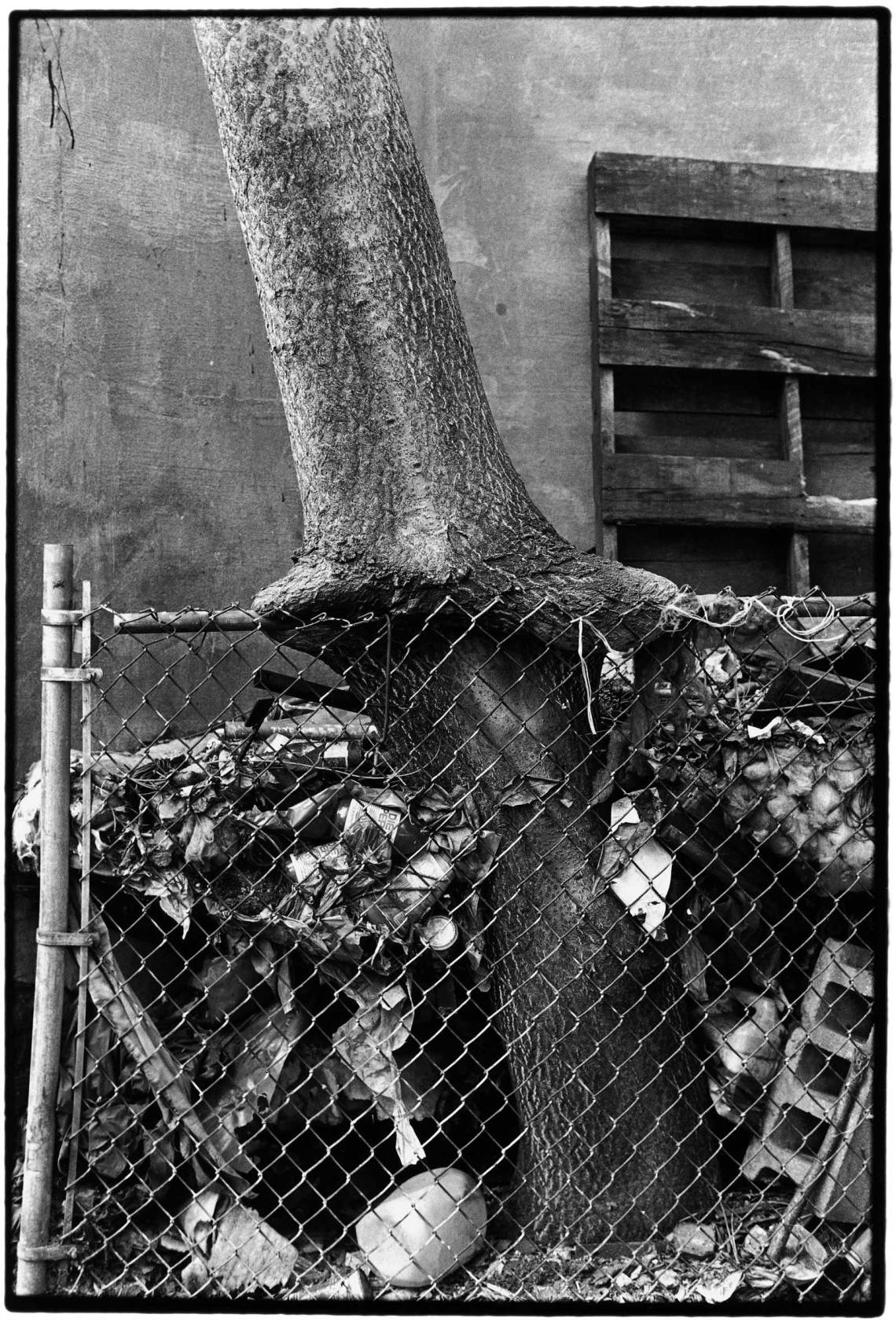

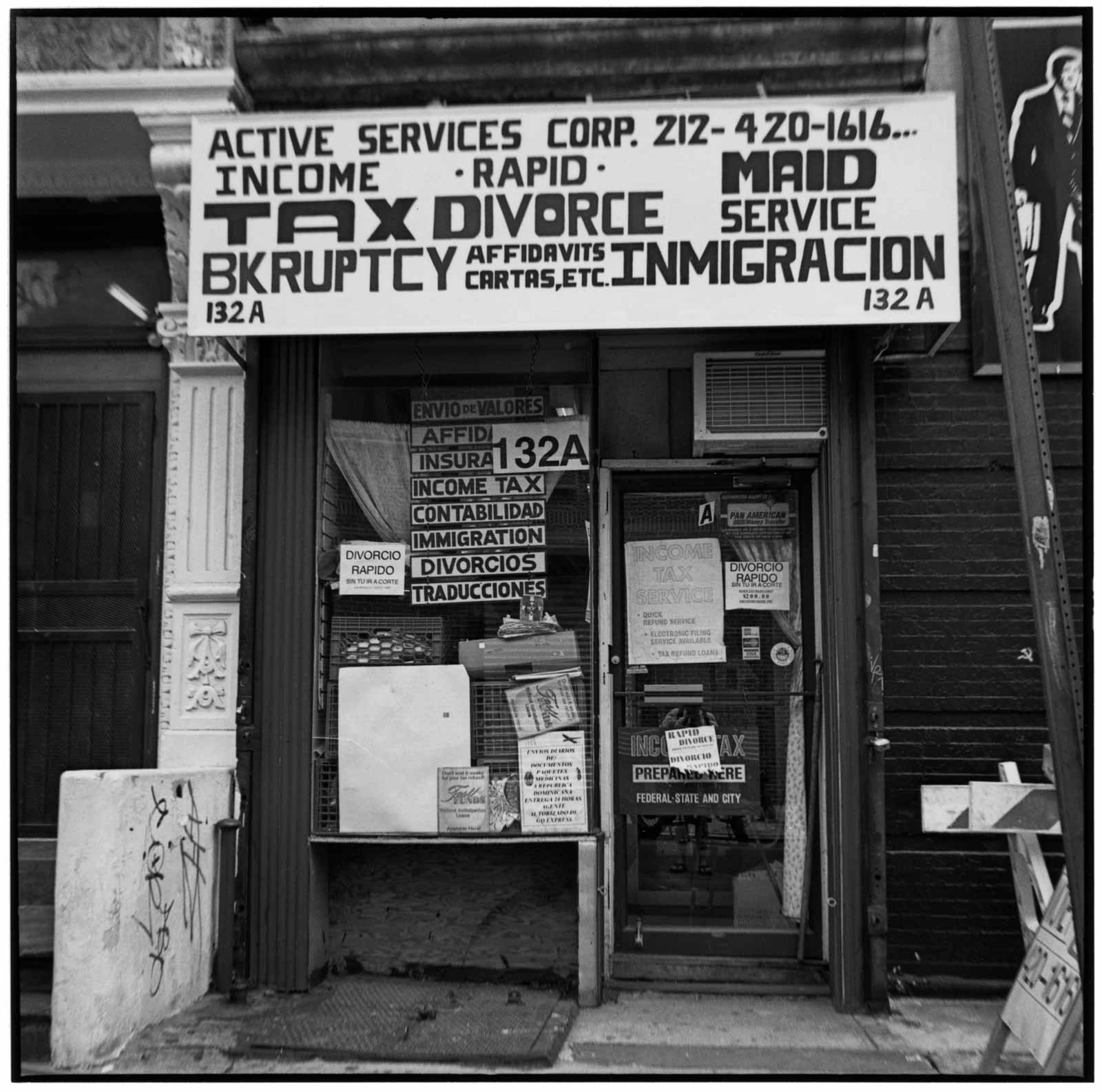

Since the 1990s, her work as an artist has been haunted by this loss. Today, much of Leonard’s photography makes visible the passage of time. Several prints show the red-painted sides of city buildings, with the bricked-over outlines of a former window. Others are black-and-white portraits of urban trees that burst through the metal fences that surround them, or warp their trunks into the hollows of a chain link fence. Looking at these photographs, there is a sense of preservation, of saving these things from being obliterated—by AIDS, by gentrification, or simply by forgetfulness—by preserving them in images.

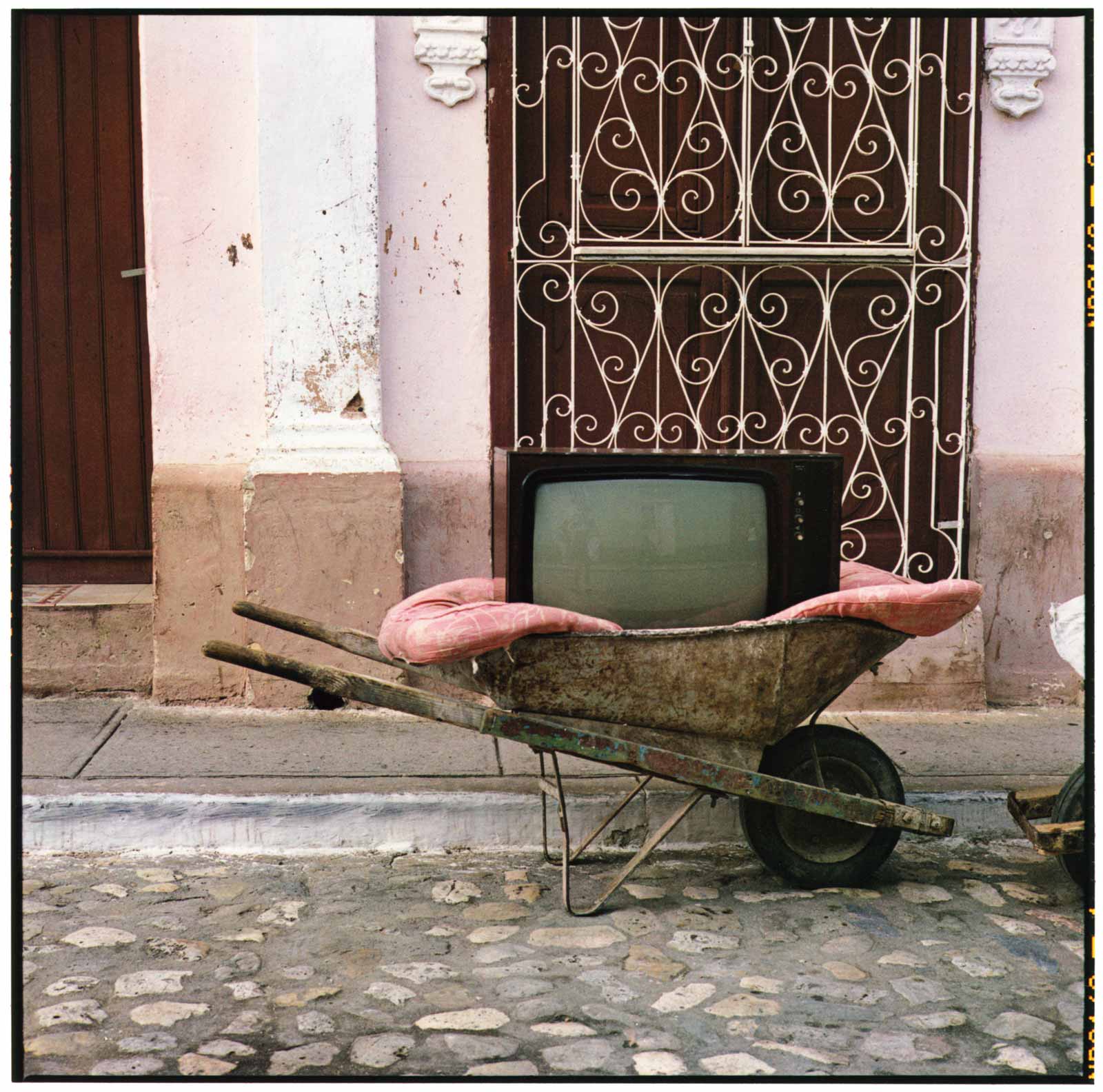

There’s a conservationist impulse, too, in Leonard’s methods, which are sometimes very old-fashioned. She has an eye for the historical and obsolete. In addition to the Fae Richards series, which uses photographic techniques from the era of the character’s imagined lifetime, there are also a number of photos made using the time-consuming, expensive dye-transfer process, a nearly-forgotten method that produces colors of unparalleled vibrancy. In a series of photos using this method, taken around the world and over the course of decades, we see mainly urban, outdoor scenes. A television sits in a wheelbarrow, swaddled in an impossibly pink blanket; a pink shanty bears a bright red sign above its door bearing one word: ARTIST. In one picture, a cardboard portrait is taped to a storefront window—looking like a prop from a children’s classroom project, it shows Martin Luther King Jr.

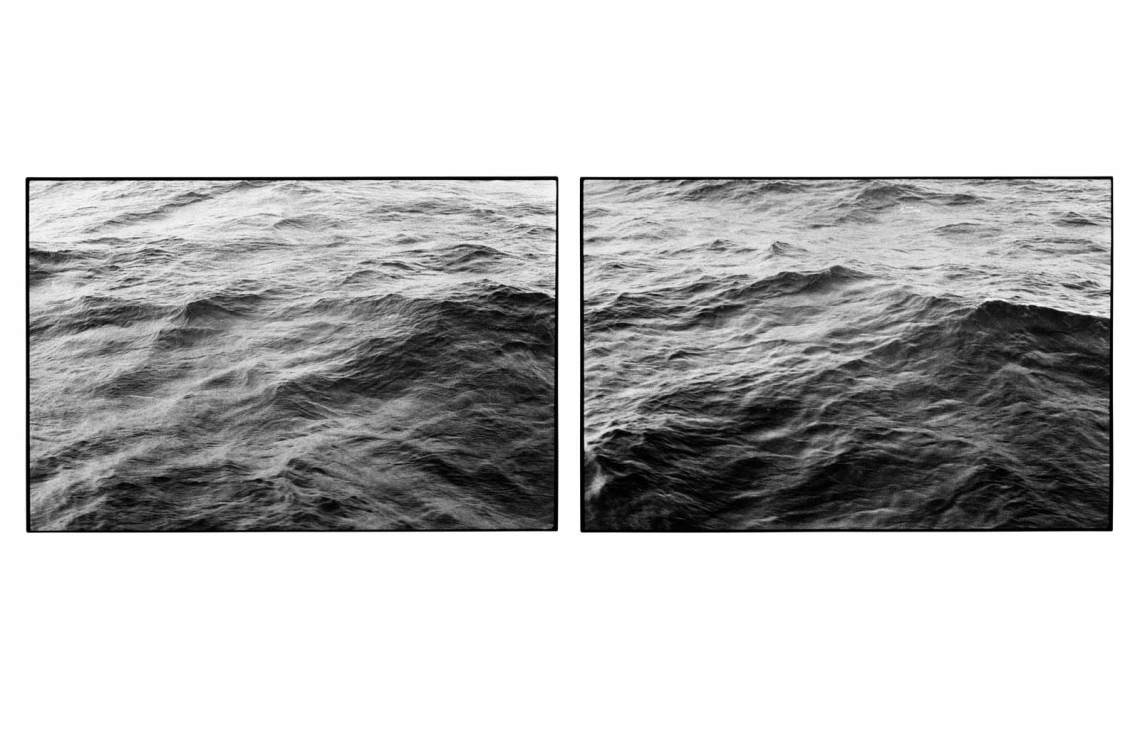

The decision to use forgotten but beautiful techniques is typical of Leonard, who is deeply invested in photography’s capacity to preserve, to reveal, and to challenge norms. She also has an archivist’s instinct for accumulation and collection. One installation, called How to Take Good Pictures, consists of 429 copies of the Kodak photography manual of that same name, collecting editions that span decades. Each edition is slightly different—over the years, the title of the manual was eventually changed from How to Make Good Pictures to How to Take them—suggesting that the measure of a “good” image is always in flux. The exhibit contains various untitled black-and-white photographs taken from unusual angles, challenging the viewer to ask why they’ve never looked at these scenes from this perspective before. The rippled surface of an unknown body of water fills one frame; another shows cottony clouds from the inside an oval airplane window.

Advertisement

One of the retrospective’s most arresting pieces is the vast installation You see I am here after all, which consists of 3,883 hand-colored vintage postcards of Niagara Falls. The postcards are mass-produced and nearly identical—some still have handwriting on the back and used stamps—but they come in different editions, each taken from a slightly different viewpoint along the falls. Leonard has arranged them along an extensive wall in order to form a panorama of the falls. As you walk along it, you see the waters from different angles, starting at the eastern end of the waterfall and moving west. Like much of Leonard’s work, the piece urges you to consider your own perspective: wherever you stand along You see, there is someone else farther down the line, looking at the arrangement from another vantage point.

Leonard’s work is assertively political, and it is difficult to look through “Survey” without being struck by reminders of our national moment. One piece, called Tipping Point, consists of fifty-three copies of James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time stacked in a teetering column; one more, we imagine, and the stack would finally fall over. In another room, the photo series New York Harbor contains several old family photos of Leonard’s own ancestors as immigrants, smiling on ship’s decks in front of American flags whipped straight by the wind, the Statue of Liberty in the background. Knowing the threats faced by immigrants today, these images are almost unbearable to look at.

In another room, an original, type-written copy of Leonard’s famous poem “I want a president” is framed behind glass. Written in response to the poet Eileen Myles’s presidential bid in 1992, the poem pushes Myles’s largely symbolic gesture further still, expressing the ache and anger of democracy’s failures. “I want a dyke for president,” the poem begins. “I want a person with aids for president and I want a fag for vice president.” Later, it demands, “And I want to know why this isn’t possible.”

But the most arresting piece in the show by far is Strange Fruit, an installation named after the Billie Holiday song about lynching. A response to the AIDS crisis, Strange Fruit took five years to create, from 1992 through 1997, and consists of dozens of fruit peels—grapefruit, banana, orange, lemon, avocado—gutted of their meat and stitched painstakingly back together with thread, zippers, and buttons. Leonard originally dedicated the piece to her best friend, the artist and activist David Wojnarowicz, who died of AIDS in 1992, the year that she began work on the piece.

The installation has its own room at the Whitney, the rinds arranged on the floor. It’s impossible not to feel moved by the idea of Leonard’s labor in creating it: the patient, tender effort of sewing the rinds back together, trying to make them whole again. It’s a testament to art as preservation, as memorial-making, but Strange Fruit also underlines the failure of grieving to restore what was lost—and what we, the grieving, were before the loss. None of the fruits look ripe; in fact, Leonard chose not to preserve them in any way; they shrivel and rot over time, with patches of bluish mold visible.

Elsewhere in the exhibit, in one of the middle galleries, there is a black-and-white photograph, taken in the early Nineties, that shows a white wall scrawled with graffiti: “GAY + PROUD + DEAD.” Wherever Leonard found it, it’s almost certain that by now that graffiti is gone, too.

Advertisement

“Zoe Leonard: Survey” is at the Whitney Museum through June 10.