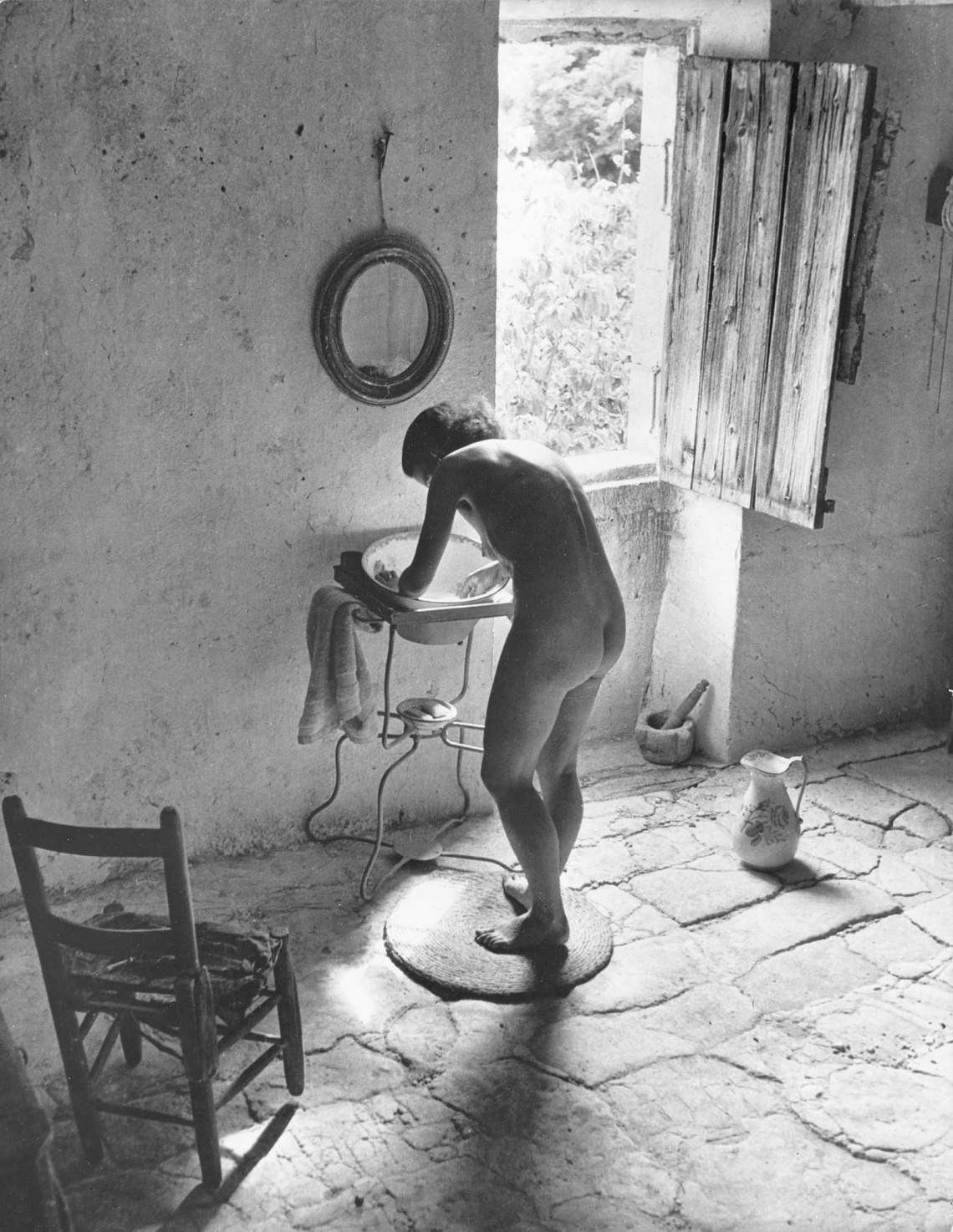

“Marie-Anne, do not move!” exclaimed Willy Ronis, who was running downstairs to get a trowel, as their little stone house in Gordes, Provence, needed endless repairs, when he saw his wife washing, naked, at their simple iron sink, surrounded by cracked stone. He captured her image from behind. To her right, a water pitcher sits on the floor and a window opens onto their garden. The summer sun caresses her back, gently delineating her curves. The 1949 picture, which feels a little like a nude by Pierre Bonnard, became known as Le Nu Provençal (The Provence Nude) and was the photograph that made Ronis’s reputation.

In France, Ronis’s work is much loved, with its focus on ordinary people and ordinary life, its sense of humanity, empathy, and grace—the anti-sensational, as it were. An exhibition of more than two hundred photographs at the Pavillon Carré de Baudoin, in the 20th arrondissement—a village-like section of Paris and one of Ronis’s favorite places to photograph—offers a chance to see his own greatest-hits selection. When Ronis was eighty-five, he organized what he considered the essential part of his work, about 600 images, into six large albums, accompanying each picture with handwritten comments. They were donated to the MAP, the French Ministry of Culture, and in the current exhibition, “Willy Ronis by Willy Ronis,” the albums can be consulted with Ronis’s handwriting on interactive tablets, while his words are reproduced in type on the walls next to his photographs.

In the spring of 2009, just before Ronis, a long-time friend, turned one hundred, I interviewed him in his Paris apartment. Until the end of his life, later that year, he was alert and engaged in his work, with vivid memories of his long career. Like that of his contemporaries Robert Doisneau, Édouard Boubat, Izis Bidermanas, and Sabine Weiss, Ronis’s work came to epitomize a certain humanist photography that flourished after the devastation of World War II, when people in Europe were hopeful that together they might build a better world.

Ronis was born in 1910 to a family of Lithuanian Jews—the same background as his friend Izis. Ronis’s mother was a pianist. His father ran a portrait studio on Boulevard Voltaire in Paris, and made what Willy described as “a type of photography that naturally I viscerally despised. He did not have any visual culture. He was a good craftsman, that’s what he was.” However, because of his father’s terminal illness, Ronis had to take over the store and for four years did the kind of work that he detested: sentimental marriage photographs, christenings and communions, retouched studio portraits. “As soon as my father died, in June 1936,” said Ronis, “I abandoned the studio to its creditors and started photographing in the street. One month after, it was the formidable July 14, 1936… I was in the street with a camera that I took from my father’s display window before the creditors seized everything… a Zeiss Ikonta Bellows camera, with a Tessar lens and 4.5 aperture.”

“It was the street I was interested in,” Ronis added, where he felt the pulse of life. Inspired by the Münchner Illustrierte and the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung, the great German illustrated magazines that showed daily life before Hitler’s rise to power, he fulfilled his dream of becoming a street photographer, an uncommon calling at the time: his pictures were published in Vu, Regards, and the communist daily L’Humanité—he had joined the Communist Party at fourteen—which reflected his belief in social progress. “Even if I knew early on that photography alone would not be able to change the world, I felt that the work of contemporary photographers could serve as a witness to contemporary life,” Ronis explained.

The photography milieu was small then: he quickly met and befriended Brassaï, Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Chim, Robert Doisneau, and André Kertész, and bought a Rolleiflex with his first savings. He later abandoned the large-format camera for a Universal Foca with a 50mm lens, a French equivalent of the Leica, which he thought was too expensive.

Because he was Jewish, in 1941 Ronis had to flee occupied Paris for the South of France, the “zone libre.” He survived doing odd jobs such as stage-managing a traveling theater troupe, creating sets for a movie studio in Nice, and painting jewelry with his wife, the painter Marie-Anne Lansiaux. He came back to Paris, after its liberation, in October 1944: “There was a whole new blossoming of illustrated magazines that needed photographers who knew how to work,” said Ronis.

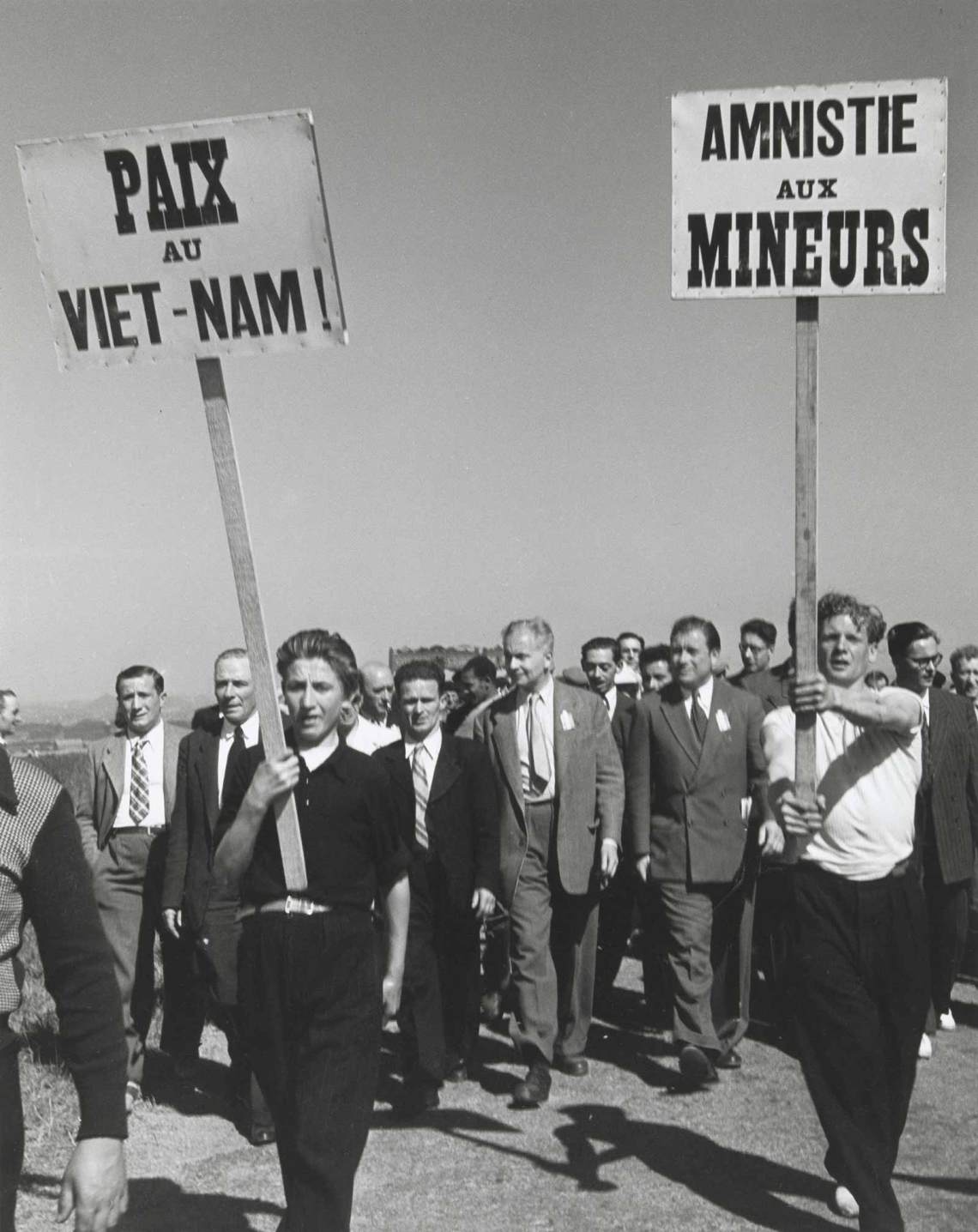

Although originally he photographed strikes, marches, and demonstrations on assignment, Ronis also made more personal pictures on the side: “I never went out without my camera, even to buy bread.” From the start, he was especially interested in Parisian scenes, and many of his classical, intimate photographs were shot in his hometown.

As it turned out, the images he made for himself rather than for the magazines were the ones where his spirit and delicate, exacting compositions are most apparent. Eighty-one of the earlier images were included in his first book, Belleville-Ménilmontant (1954), with a beautiful text by the poet Pierre Mac Orlan. The pictures were made between 1947 and 1950 in an out-of-the-way neighborhood in Paris: “It was a village on the hills, with a marvelous light… The tourist buses never went there, there were no monuments, people kept to themselves.”

He also photographed in many more Parisian neighborhoods, even in the beaux quartiers, the chic and central neighborhoods with their stately buildings, jewelers, and design stores. In Place Vendôme, a woman’s legs, blurred by movement, scissor across a puddle, with the obelisk reflected upside down in the water. She was a cousette, sewing for one of the haute couture studios, and on her way to a quick lunch before resuming work. An intimate picture of a couple made on Place de la Bastille, at the top of the July Column, reveals a panoramic view of the sky and the capital’s roofs and monuments displayed behind the balcony’s wrought iron curlicues. They kissed just as he was looking. In another, a little boy in shorts with a radiant smile runs home, a baguette under his arm. In a photo from the late 1970s, people are lost in conversation on public phones in the then-new Châtelet-Les Halles metro station, their faces hidden by the curvy cabins—a wry comment, even more so today, on the isolation and anonymity of contemporary life. “I had the vague sensation that I was witnessing the savage meal of a group of carnivorous plants disguised as phones to better deceive human beings,” Ronis commented.

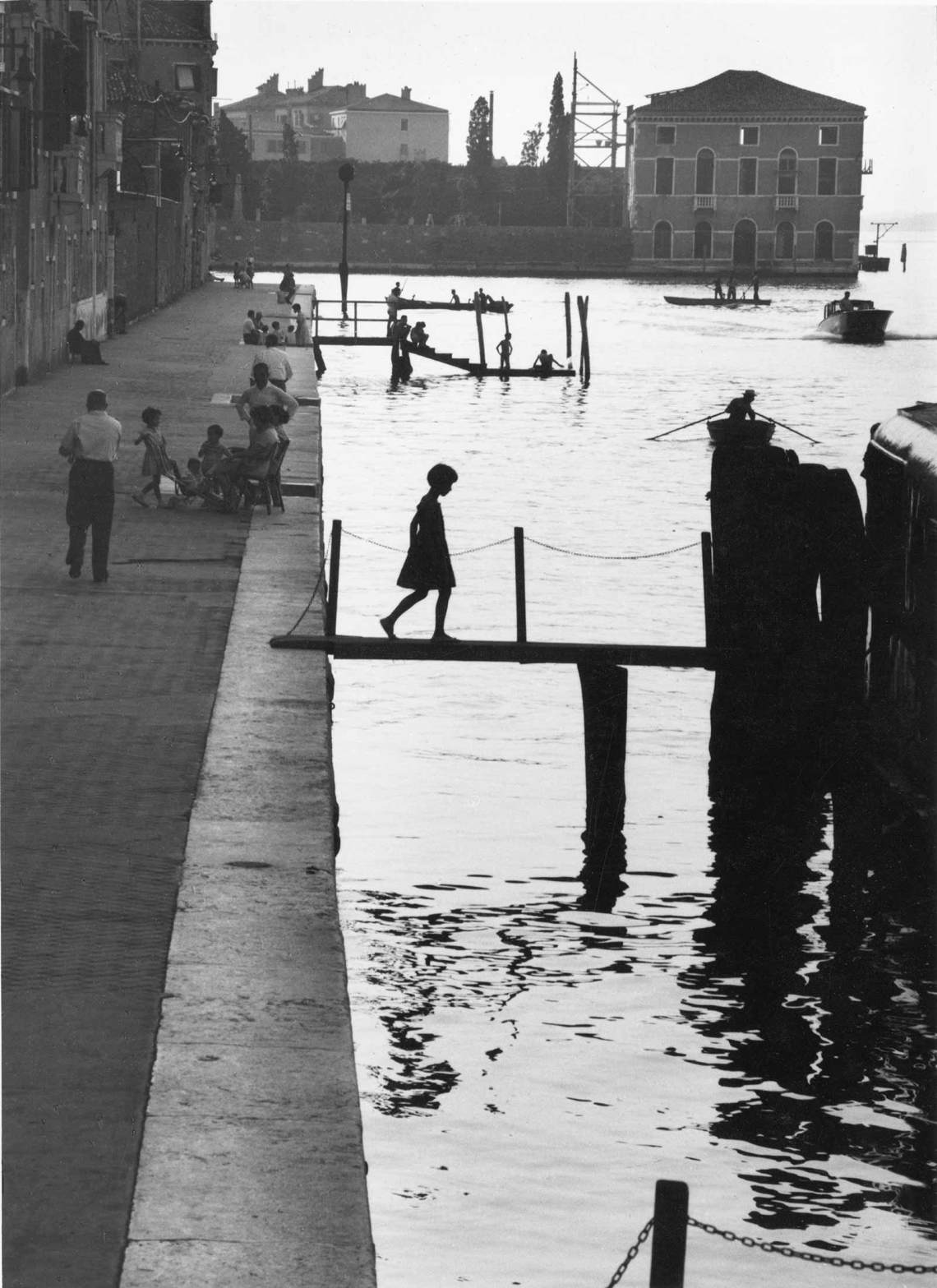

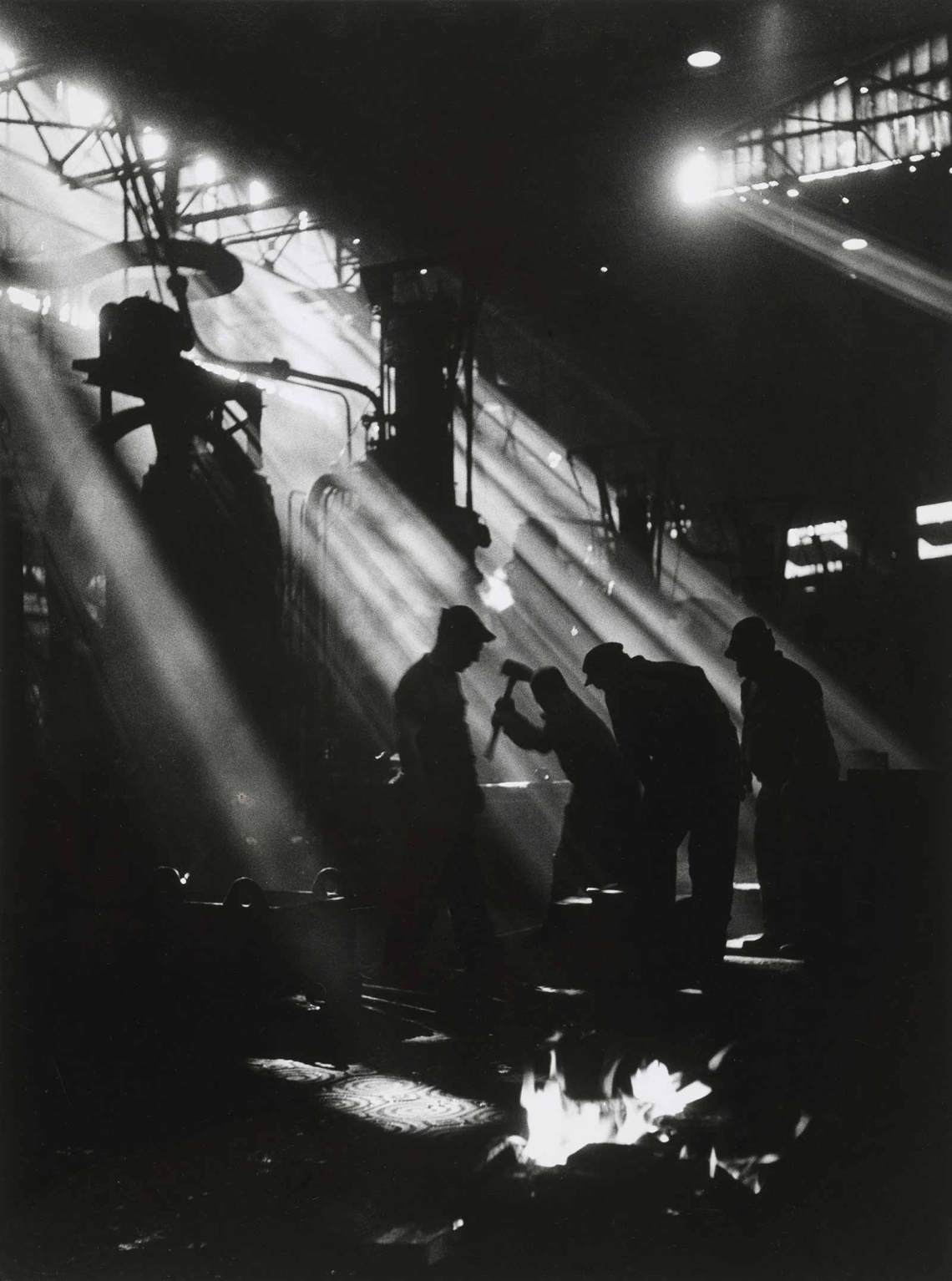

While many images—such as the famous Nu Provençal or that of his son Vincent flying a model airplane—convey a tender, romantic spirit, others, born of his engagement with leftist politics, are much starker, with strong chiaroscuro. (Tragically, Vincent would later die in a hang-gliding accident, a sport that Ronis also practiced well into his eighties.) In the spirit of his May 1936 beginnings, when one million people demonstrated to support the Popular Front government, Ronis regularly covered demonstrations and strikes, conflicts at the Citroën and Renault car factories, the harsh worlds of the miners in Saint-Étienne in the north of France, and of the textile industry in Alsace-Lorraine. He also traveled to the Mediterranean, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, England, the United States, Réunion Island, and even to Moscow, Prague, and East Germany during the cold war, doing personal work and commercial assignments, often for Vogue.

Advertisement

Even in the mid-1930s when working on assignment, Willy Ronis always requested that his photographs not be cropped and his captions not be changed—not the common practice for photographers at the time—which caused numerous professional conflicts, notably with New York magazine, which published his portrait of a trade unionist with a sarcastic caption. Though hurt by such callousness, he continued to accept magazine assignments and publicity work, but he chose his clients carefully.

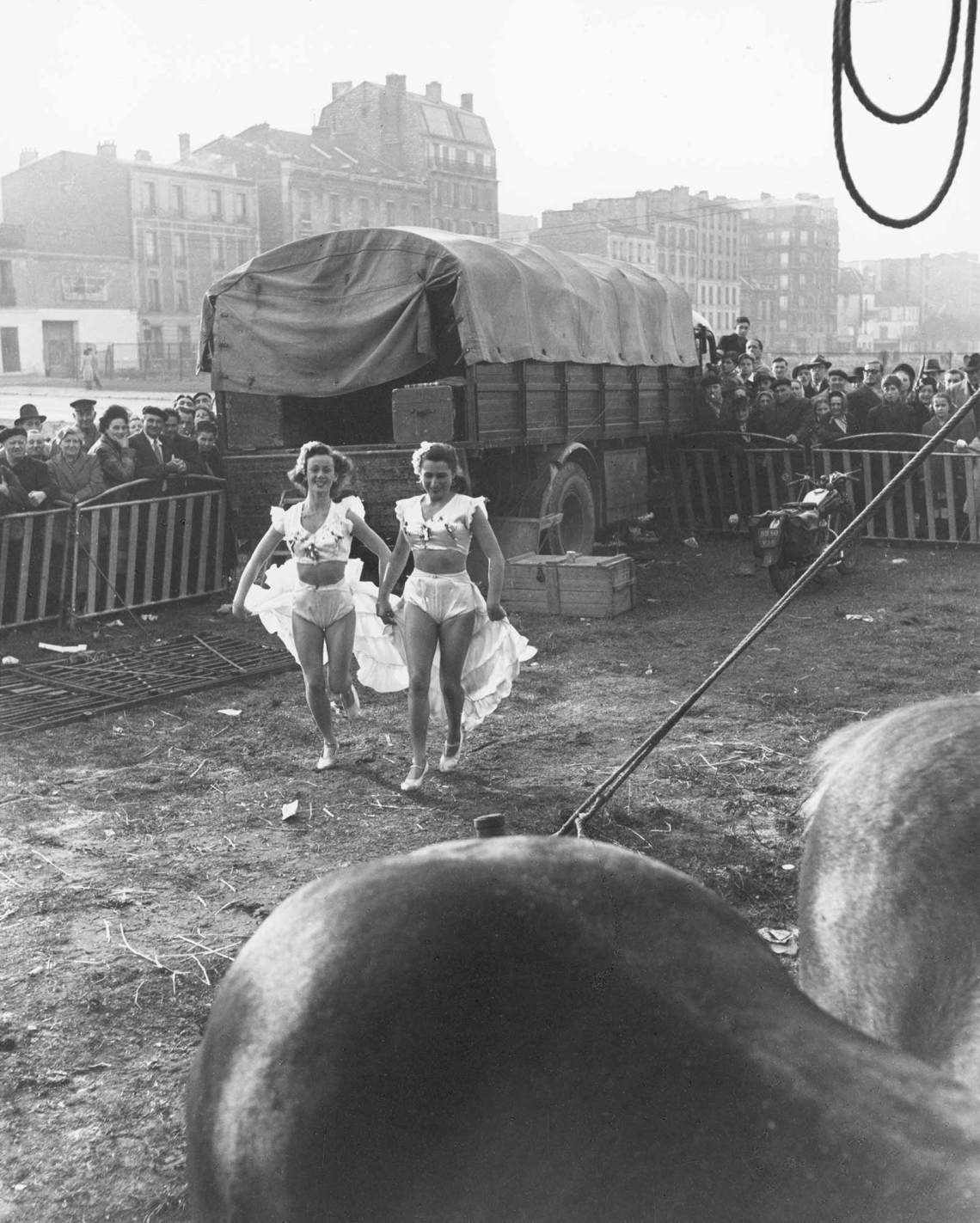

Music was Willy Ronis’s first love; and although, because of his father’s illness and his family responsibilities, he could not become a composer, music can still be felt in his work, a subtle force within his beautifully composed images, lending harmony, poise, and rhythm to the most seemingly banal subjects. In July 1947, at Chez Max an outdoor ball, a bal-musette, in Joinville, near the Marne river, Ronis saw a young man dance and whirl with two girls, their skirts outstretched like butterfly wings. Ronis gestured to him to come closer for a better angle. When the music stopped, the youngster limped away: he had a clubfoot. But in Ronis’s photograph, his natural grace, caught in the instant, endures.

“Willy Ronis by Willy Ronis,” is on view at the Pavillon Carré de Baudoin through September 29.