Dulwich Picture Gallery in high summer. A bus ride away from the city dust, we sit in the shade or eat lunch outside at the café. While I was there, a bunch of schoolgirls appeared, wearing straw boaters of all things—I thought those had long disappeared. The tone is gentle, genteel, a virtual parody of Middle England. Some visitors would say the same about the current exhibition of prints and watercolors by Edward Bawden: seaside scenes, wallpaper with cows in a zig-zag field, a village policeman on a bicycle, famous London railway stations. Some critics mutter “tame” and—dread word—“charming,” and sneer at the twee marketing of Bawden’s prints on greetings cards, handbags, kitchen tea-towels, and fridge magnets. But there’s more to Bawden than that. His admirers proclaim him as a mischievous genius, an edgy, brilliant designer, blending tradition with modernism. Yet the question echoes, as it so often does for those who follow a commercial career: Is he “a proper artist”?

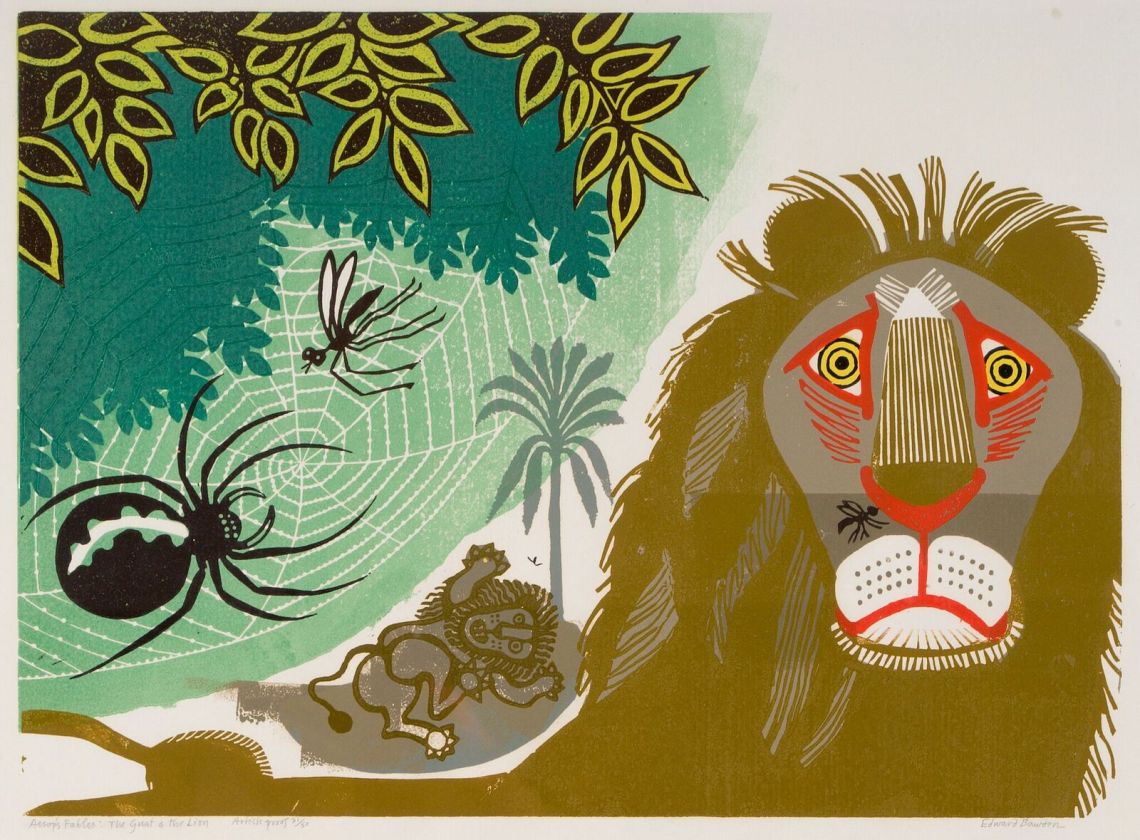

Born in 1903, the son of an Essex ironmonger, Bawden was a solitary child in a strict Methodist family—his chronic shyness hiding an eccentric, wicked wit. From his teenage years, he wanted to be a book illustrator. He won a scholarship to the Design School of the Royal College of Art, where he was taught by Paul Nash, with Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore, and the fellow student he met on his first day there in 1922 who became his close friend, Eric Ravilious. After Bawden returned from a traveling scholarship to Italy in 1925, commercial work came quickly: a brochure for Poole Pottery brought employment with the pioneering Curwen Press; a poster for the London Underground (for which he and Ravilious later produced many designs) showed off his boldness of style; a playful series of travel advertisements with drawings based on place-names for Shell gained public affection. It was the start of a design career that ranged from wallpapers, textiles, and grand murals to linocuts for an edition of Aesop’s Fables and adverts for the upmarket London grocer Fortnum & Mason.

The curator of the Dulwich Gallery’s show, James Russell, has arranged it thematically rather than chronologically, thus bringing out both the continuity of Bawden’s work and the shifts in its emphasis and technique. As you walk in, nodding to the resident Gainsboroughs and Poussins down the corridor, there’s an immediate summery, holiday feel. The exhibition opens with posters for movies like The Titfield Thunderbolt (1953), a comic classic in which an old steam engine is brought in to save a small branch line: the poster catches the tone perfectly, with a vicar shoveling coal while onlookers cheer and wave. This room is labeled “World Off Duty,” the title of a book Bawden illustrated in 1947. Taking time off, we might fly away, like the passengers in the buzzing planes of his pullout brochure for Imperial Airways, or simply stay at home and lounge in deckchairs, as in his painting By The Sea (1929–1930). The centerpiece is the huge, exuberant Map of Scarborough, made in 1931 for Bawden’s hotelier friend Tom Laughton. Laughton appears at the foot of the map with a cigarette in his mouth, wearing a rose-colored sweater with the word “Skylark” on it, while the artist pictures himself perched on a windowsill sketching the beach below, where girls in swimsuits mingle with fur-cloaked dignitaries. In the sea, mermaids frolic and a worried-looking Poseidon on a wobbly platform drives his steeds toward the shore.

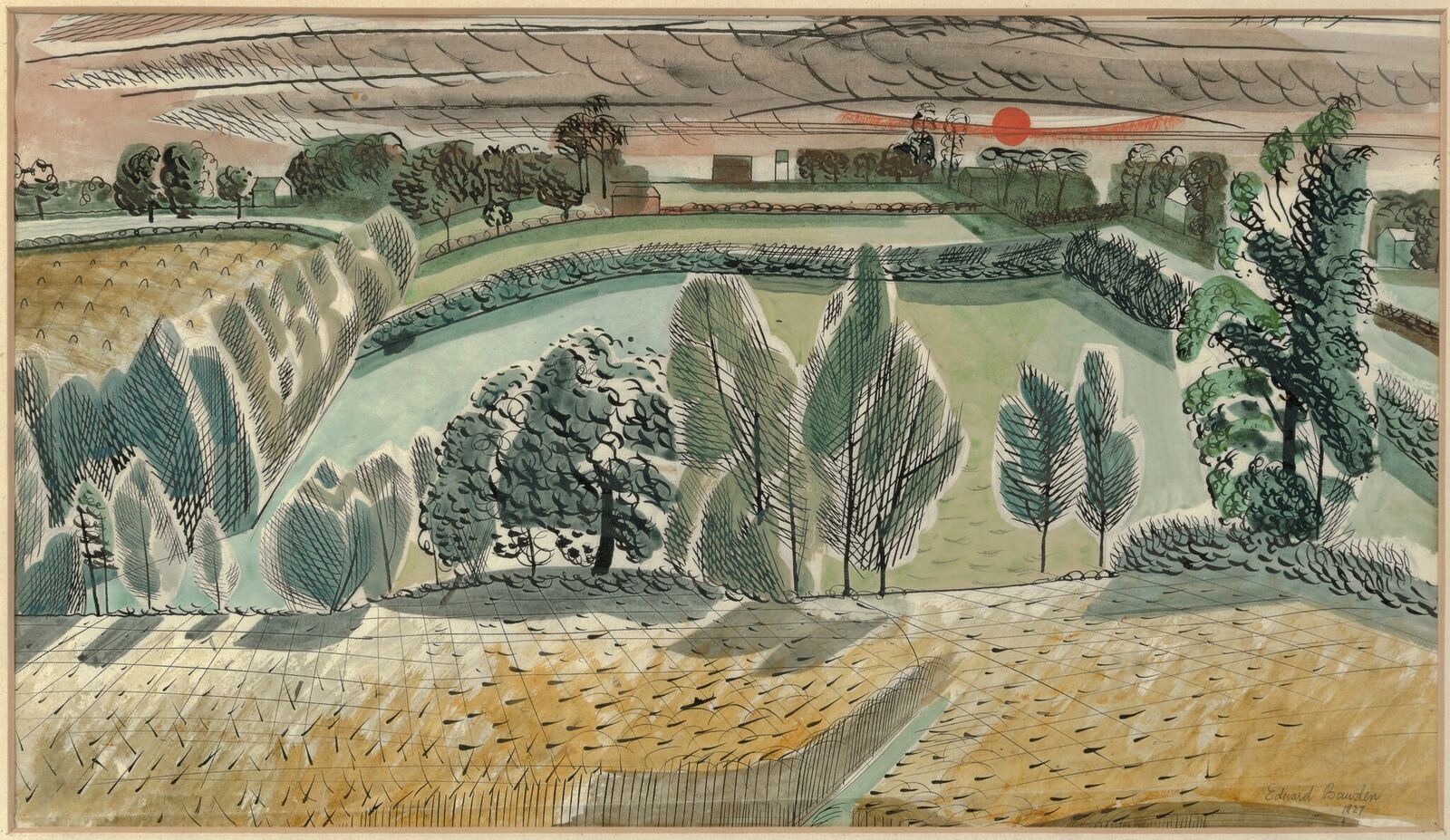

This mix of fantasy and realism appears, too, in the next room, labeled “Gardening.” In the summer of 1931, Bawden and Ravilious, with Ravilious’s artist wife, Tirzah Garwood, rented Brick House, in Great Bardfield, Essex, as a summer retreat; the following year, when Bawden married the potter Charlotte Epton, his father bought them the house as a wedding present. From then on, Bawden became a passionate and knowledgeable gardener. His early work is almost that of a miniaturist, abounding in detail. In the copperplate of Mount Pleasant Road (1927), a women reads in a hammock while a man burns leaves, fanning away the smoke; in Francis Bacon’s Garden (1928), tiny men dig with tiny spades and minuscule women gossip in a corner.

Comedy is always near. In the drawings for Ambrose Heath’s cook book Good Food (1932), organized by the month, June has two children crawling greedily under a strawberry net, like rabbits; in July, anxious men eye prize vegetables, while butterflies and bees soar out of the winner’s cup. These works, and the illustrations in many more books, are seemingly slight, yet they zing with Bawden’s spirited, springing freedom of line. Nature blooms against straight walls. The drawings are ingenious studies in perspective, pattern, geometry, and form, with astonishing use of cross-hatching and criss-crossing lines—enduring features that would strengthen the garden and village linocuts of his later years, such as The Road to Thaxted (1956) or the posters he made for the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew.

Advertisement

Bawden’s watercolors are far less well known. They show the same concern with form but feel more tentative, infused with an odd melancholy. Early works like March: Noon (1936), in a room titled “Spirit of Place,” owe much to Paul Nash, with his insistence on the genius loci, but much besides to landscape artists like Francis Towne, John Sell Cotman, and Samuel Palmer, with their rhythmic curves and delicate washes. Determined to revitalize watercolor painting, Bawden and Ravilious worked side by side, often literally so. But Bawden’s paintings are more uneven, some magically capturing angles of light, others appearing flat or uncannily surreal. They seem like attempts to answer questions such as: How can one evoke rain? How can one catch slanting sun, an autumn gale, a house blinded by snow?

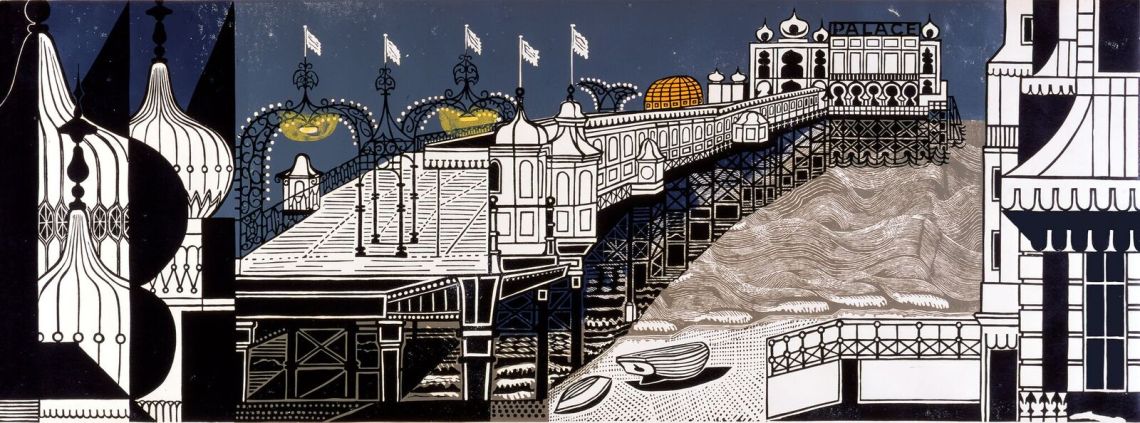

He was more secure when depicting buildings—he always loved architecture—and that skill never failed him, as can be seen in the eerie, lyrical watercolor Menelik’s Palace: The Old Gebbi (1941). Later, when the formality of linocuts, such as the exhilarating, stylized Brighton Pier (1958), began to influence his painting, he created powerful contrasts of curve and line—as in the still-life Agave from the 1970s, in which the bending fan of leaves plays against the static verticals of window, wall, and door.

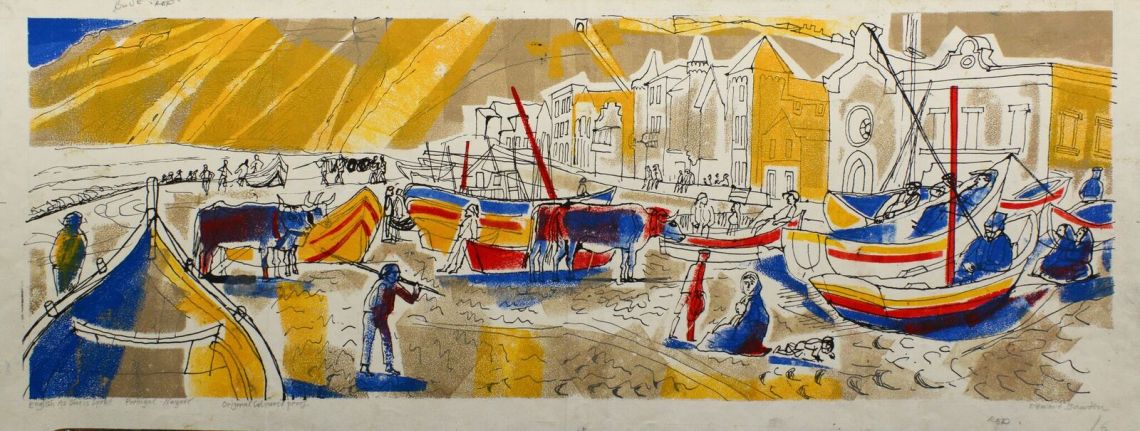

The most surprising works at Dulwich are the portraits and crowd scenes Bawden painted between 1940 and 1945, when he was an official war artist. This posting took him on a “Cook’s tour,” as he called it, from South Africa to Ethiopia, Lebanon, Iraq, and Italy. If, in the past, he had found life-drawing difficult, then faced with this challenge he was superb, immediate, direct—witness the finely-clad and anxious-faced Sergeant in the Police Force formed by the Italians, drawn in Ethiopia after the Italian defeat in 1941.

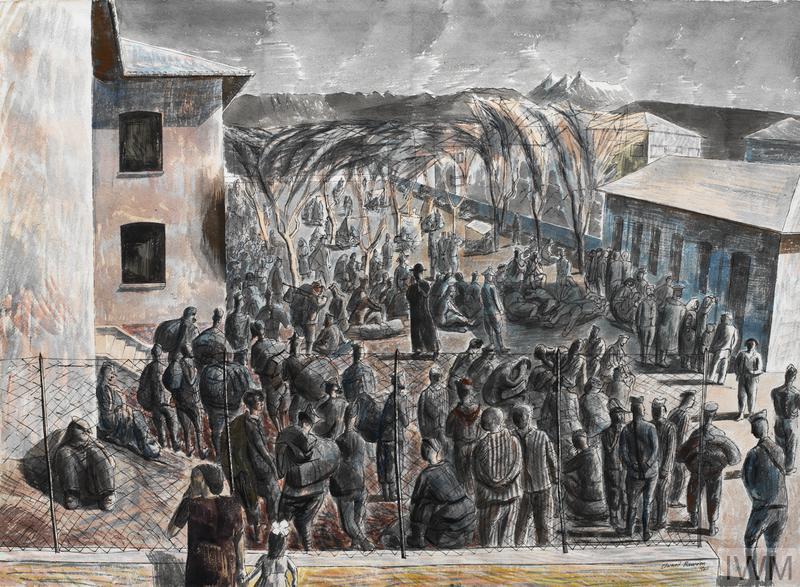

Bawden portrayed nurses and soldiers, grand sheikhs and poor coffee-bearers with equal weight and humanity. In Greece and then in Italy, with Edward Ardizzone and other artists, during the later phases of the war, Bawden saw horrors, including starving slave-workers trekking home from Germany. The most haunting picture here is Refugees at Udine (1945). Bawden had himself been interned in Morocco after a ship he was aboard was torpedoed, and his sympathy is manifest. Men stand behind a fence, some still in prison stripes. Others lie on the ground, or slump, head in hands. The priest in the center of the watercolor can offer little succor, but the trees bend over the refugees like a canopy, and a woman and girl with a flower in her hair peer through the fence’s mesh, perhaps searching for someone. There is a small hope here, too.

Arriving home after the war, as James Russell explains in his superb catalogue essay, Bawden returned to a world that seemed to have moved on. He never spoke of Ravilious, who was lost, aged thirty-nine, when his plane went down off the coast of Iceland in 1942: those who knew Bawden well believed that he never recovered from his friend’s death. He continued with posters and book jackets and advertisements, and with large-scale projects like the extraordinary screen for the Festival of Britain in 1951, and he took up a succession of teaching posts: students remember him as taciturn and prickly, but unfailingly generous when he saw talent.

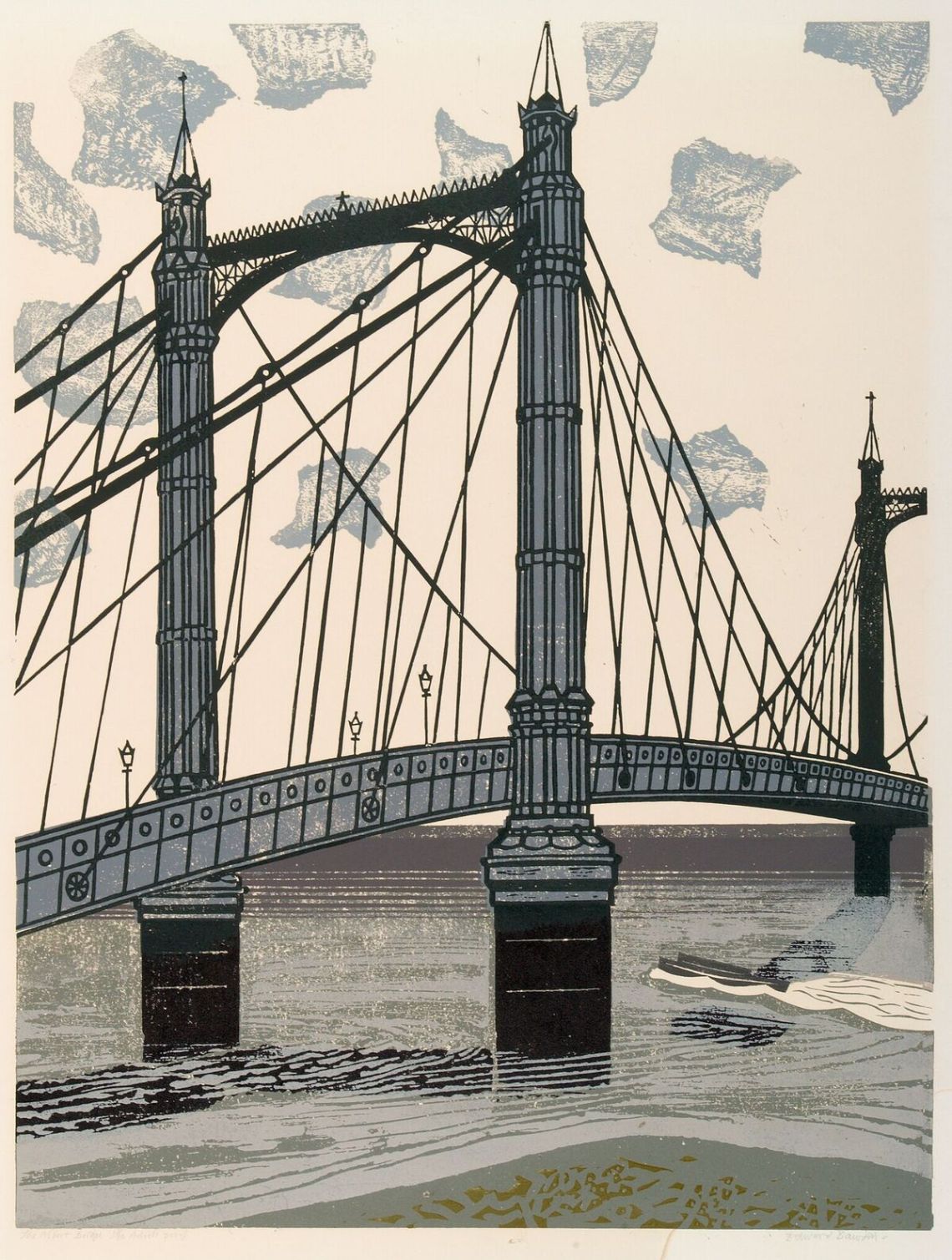

In time, Bawden found a new style to fit the new age. In the 1960s, his linocuts celebrated the humor and hard labor of London markets, but also the glories of Victorian engineering—visible on a grand scale in Liverpool Street Station (1961) and the soaring Albert Bridge (1966), which are visual anthems that hymn the complex harmonies of those structures’ iron lattice-work. And with Bawden’s formal brilliance goes a tender, amused feeling for the value of all life—from the seaside tourists of the 1920s to the war-time soldiers, from the creepy-crawlies of Snails for All, drawn for his children in 1945, to the snarling Tyger! Tyger! of 1974.

Advertisement

After seeing all these, who can say that Edward Bawden, this serious if unclassifiable artist, is merely a purveyor of charm?

“Edward Bawden” is at the Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, through September 9, 2018.