“World War II did not really end for the Japanese until 1952, and the years of war, defeat, and occupation left an indelible mark on those who lived through them,” writes the historian John Dower in Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II. This was certainly so for the manga artist Tadao Tsuge (born 1941), who made a gritty fantasy world out of post-surrender retrospection, filling his story-vignettes with landscapes and characters derived from the war’s ruins and the black markets and slums that flourished around them.

While Tadao’s work is a unique intervention into the literature of war memory, it also speaks to issues of class, geography, and the built environment. The artist’s apathy toward political organizing was overt. Nonetheless, his late Sixties and early Seventies comics were fairly close in spirit to the work of labor activists, anarchist writers, and photojournalists who were concerned about the neglected armies of men who manned the lower echelons of Japan’s booming construction, manufacturing, and energy industries, often via yakuza-mediated day-labor markets in big cities like Tokyo, Yokohama, and Osaka.

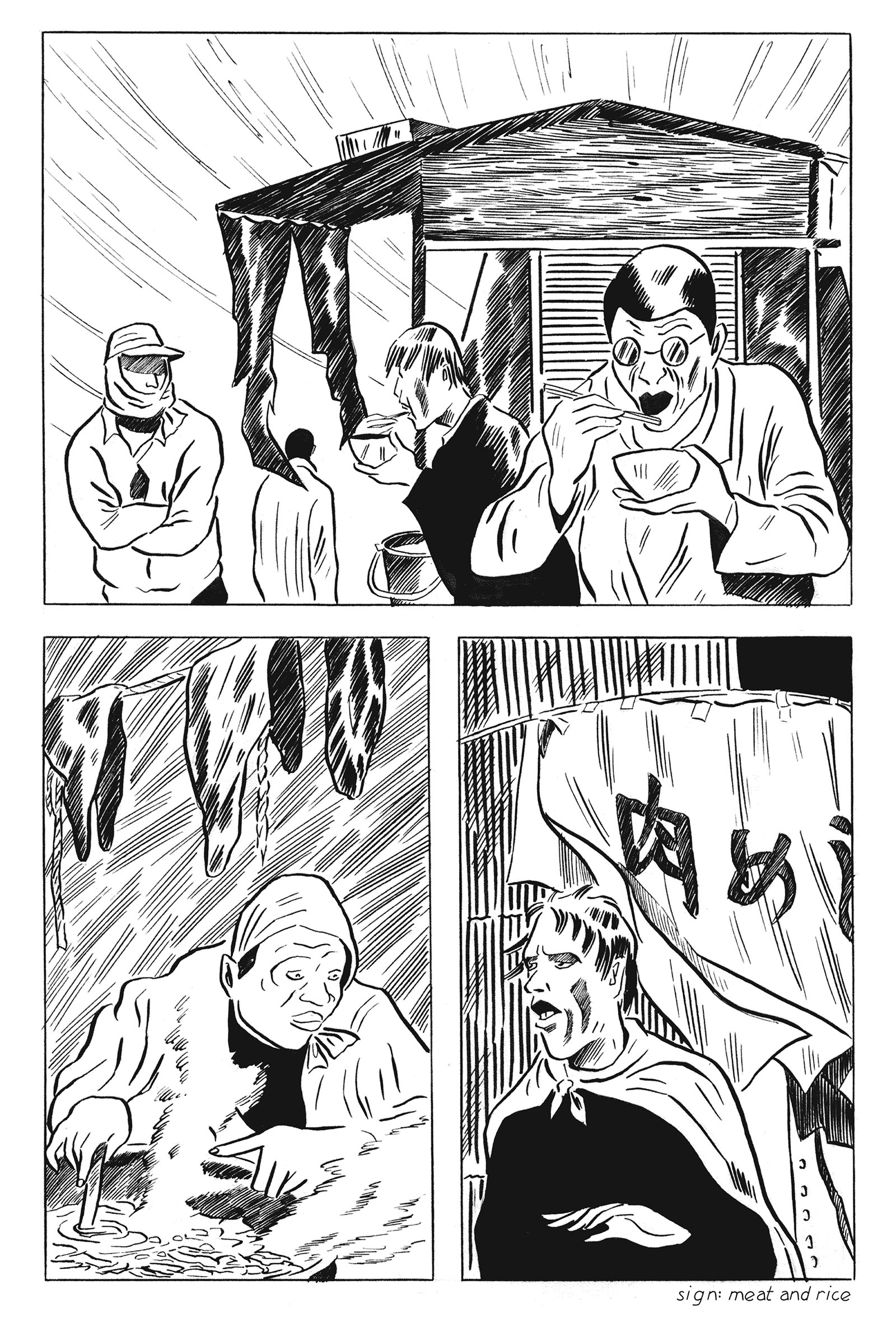

Until the late Sixties, such informal labor markets (known as yoseba) were also where blood banks like the one where Tadao worked went to recruit when supplies were low. They were where major corporations like Toyota scouted men to work their assembly lines, usually on grueling shifts and under dangerous conditions for terrible pay. Corrupt day-labor markets were also where the fledgling nuclear power industry and their yakuza go-betweens went to find short-term janitorial and maintenance workers, to be shipped off to places like the Fukushima Daiichi station (already notorious as a dirty and dangerous facility in the 1970s) to wipe up radioactive spills and remove radioactive corrosion from valves and vents, so that Japan’s nuclear power plants were clean enough to pass inspection and reopen with tolerable efficiency and without too great a risk of accident.

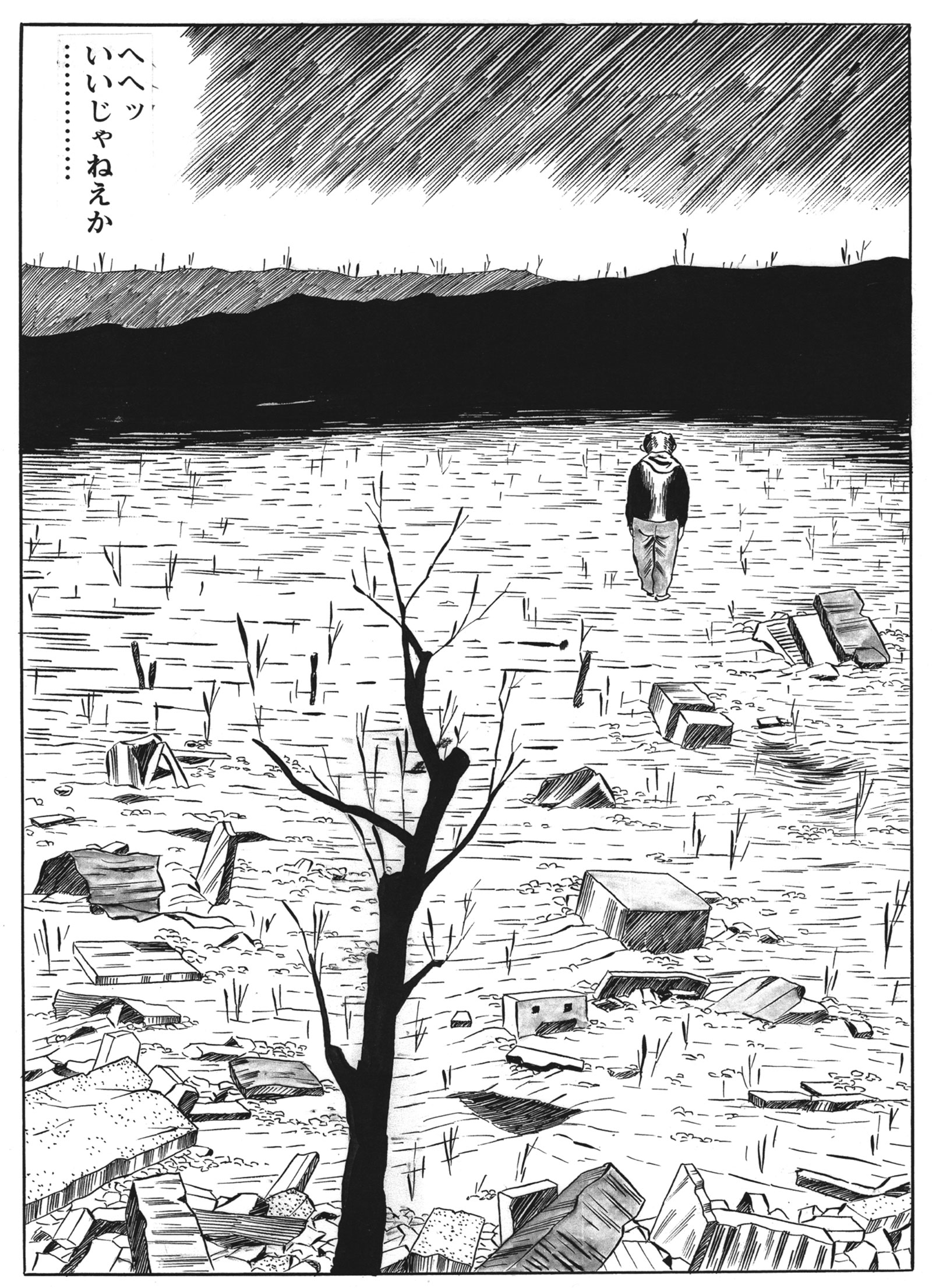

Many writers took to calling these exploited laborers kimin—“abandoned peoples”—thereby identifying the day-labor markets, and the alliance between industrial capitalism and organized crime that governed them, as one of the major engines of dispossession in Japan. As time passed, Tadao’s work moved away from actual kimin sites and peoples. His careful depiction of Japan’s human “trash markets” (his name for the blood banks and the colorful riffraff that congregated there) in the late Sixties and early Seventies mutated into generalized fantasy zones situated vaguely on the undeveloped fringes of Tokyo. “Vagabond Plain” offers the most detailed such rendering, though one finds nondescript riverside embankments and wastelands as settings for social flight and perverse sex even in his earliest works for Garo.

A further twist on the zone’s evolution was provided twenty years later, with his two-volume graphic novel Dwelling in a Boat (Fune ni sumu, 1996–2000). Almost the entire story takes place in a real-life grass zone on the Tone River in Chiba prefecture, twenty miles north of Tokyo, near where Tadao has lived since the 1970s. One character, a stand-in for the artist, wishes to spend his last years living on a small, rickety houseboat, allowing the current to take him where it will. Meanwhile, his friend has developed a taste for modernist junk sculpture, and spends his days hauling rubble into an overgrown field, smashing it with hammers, and then carefully burning the vegetation to create a simulation of a bombed-out city. “It sends shivers up my spine,” sighs one of the characters as he gazes upon this wonderfully anachronistic outdoor installation.

With this page, Tadao pulled the plug on the zone’s black magic. Back in the mid-Seventies, at the time of “Vagabond Plain,” elaborating a world of ruins called for no such irony. Popular images of a nation composed of neon-lit cities and industrious white-collar workers notwithstanding, ruins and ruined people remain an important part of Japanese national identity. One of the country’s top tourist sites, after all, is the skeletal brick-and-steel remains of a former government exposition hall near ground zero in Hiroshima—the Atom Bomb Dome—while the hibakusha (those exposed to the blast and radiation in Hiroshima and Nagasaki) have long stood as Japan’s emissaries of world peace. Though Garo founder Sanpei Shirato was committed to peace activism and used the magazine as a platform to that end in the mid-Sixties, most other artists and critics associated with Garo shrugged their shoulders at the kind of humanism the hibakusha and their supporters stood for, just as they dismissed organized politics. Many of them were drawn instead to the ambivalent figure of the combat veteran: the killer who was also a victim of reckless imperial ambitions and an inhuman military culture. They were also intrigued by the ambivalence that many people of their parents’ generation expressed (though usually in hushed tones) about life during the war. In a 1969 interview with Garo editor Shinzō Takano, Tadao reflected:

Advertisement

People our age, we only really comprehend what happened at the end of the war. At night, from the air-raid shelters, we witnessed airplanes in flames streaking across the sky. That’s all the war was for us. But for them [people who were adults during the war], they had to deal with a variety of problems when the bombs fell… There must be a lot we don’t know about. Talking to people, you often hear them say that they never want to go to war again, that the war was really horrible. Yet, I feel like that’s not the whole picture… War war war consumes one’s life like a fever, then all of a sudden it’s over. How does someone live life after that? Were they able to just, snip, start fresh? They don’t look bothered now, but who knows what they’re really feeling…

This preference for moral ambivalence can be seen clearly in Tadao’s taste in architectural ruins. While generally his wastelands suggest firebombed Tokyo, at the center of “Vagabond Plain” stands a monument from another city, the wrecked masonry edifice with a “giant tuna steak of a chimney.” The narrator describes it as belonging to a famous munitions factory, referring most likely to the ruins of the Osaka Artillery Arsenal, a forgotten but important facility that once stood in the heart of Japan’s second city. Situated just east of Osaka Castle, the arsenal was the largest such factory in Asia until American bombers obliterated it on August 14, 1945, the day before Japan surrendered. “That Roosevelt, he knew what he was doing,” muses the story’s narrator. “They left that chimney standing on purpose,” meaning, presumably, with the intent of rubbing superior power in the Japs’ faces.

While Occupation authorities liquidated most of the surviving machinery and weaponry at the Osaka Arsenal, a treasure hoard of scrap steel and other metals still remained when Japan regained national sovereignty in 1952. It was so valuable that the site was known colloquially as the Sugiyama Gold Mine, after the district in which it was located. Over the next few years, the arsenal’s carcass was picked apart and sold on the black market by teams of scavengers who lived in a shantytown across the river that ran beside it. Among the literary works inspired by news coverage of the arsenal’s plundering was one of Tadao’s favorite novels: Takeshi Kaikō’s Japan Threepenny Opera (Nihon sanmon opera, 1959), which focuses on the social organization of the scavenger’s settlement.

Kaikō calls the place “Osaka’s Casbah,” as it is led by stateless Koreans and filled with “ex-convicts, wanderers, the formally unemployed, and illegal aliens, all of whom come like the wind and go like water.” He presents the place as a kind of kimin utopia where freedom and order were promised by a meritocratic anarchy that did not recognize the social hierarchies, class privileges, or prejudices of the outside world. He calls its inhabitants “Apaches,” after the name the Osaka police used in real life to honor the scavengers’ speed and muscle, and their choreographed hit-and-run attacks—“Apaches” as in John Ford’s Apaches, who were well known to Japan’s many fans of Hollywood Westerns like Stagecoach (1939) and Fort Apache (1948). The appellation was presumably meant as an innocent pop culture reference, but was apposite given Native Americans’ fate as the United States’ own colonial kimin.

Though Tadao’s ruin fantasies are rarely political in an admonitory way, they do stake a claim on memory, on who should get to remember what and how. The shadow appearance of the Osaka Arsenal in “Vagabond Plain” reaffirms what the slum wolves and traumatized men elsewhere in his work establish: that the war’s ruins did not belong equally to everyone, and could not be appropriated so simply as monuments of melancholic peace. Even a place like Hiroshima was guilty on this count. As many historians have argued, a singular focus on Japanese hibakusha as World War II’s exemplary victims obscures much about Hiroshima’s history and the selective nature of Japanese war memories. For example, many hibakusha of Korean descent, brought to Japan as conscript laborers, were, until recently, refused the benefits provided to Japanese atomic bomb victims. The Hiroshima area’s repressed history as a major military center is also frequently highlighted.

Advertisement

Closer to the concerns of the present inquiry is the fate of the so-called “atomic bomb slum” (genbaku suramu) that once neighbored the Atom Bomb Dome. A sprawling and labyrinthine settlement of rickety shacks on land that previously housed various military structures, it provided shelter to an assortment of kimin: pariah burakumin, Koreans, and ailing and disfigured hibakusha who feared going out in public and whose care was hampered by government bureaucracy. In the honorable tradition of urban renewal, Hiroshima progressively cleared the atomic slum in the Sixties and Seventies and replaced it with parks, museums, and other municipal leisure facilities, as well as with a fancy, modernist public housing project. Because they were technically squatters on government land, the slum dwellers were compensated little or not at all for their displacement. Kimin, and the challenges they posed to a monovocal narrative of Hiroshima’s identity, had no place in the new City of Peace.

Tadao, meanwhile, was erecting new slums in pen and paper around uncelebrated war ruins precisely so that the rootless could continue to have a homeless home, at least in fantasy. With a good-natured smile, Tadao often laments his work’s lack of wide readership, blaming its bleakness and loose drawing. He should take it as a compliment instead. It is a reflection of his art’s refusal to pander to popular Japanese tastes for upbeat and redemptive depictions of economic hardship and social marginalization, its refusal to give in to the compulsion to cast Japan’s defeat as a long-gone event still capable of moving the masses emotionally but without any material or social legacies worth thinking about critically. Tadao should, in other words, take pride in his zone’s integrity as an exclusive and well-fortified utopia. He invites you to visit. He will even show you in. But do not expect him to make you feel at home.

Adapted from the afterword to Tadao Tsuge’s Slum Wolf, published by NYR Comics.