It has been a remarkable summer for Tacita Dean in Britain. This versatile, genre-defying artist has enjoyed three concurrent retrospectives at the National Gallery, the National Portrait Gallery, and the Royal Academy, three of the biggest art museums in the UK. It is an honor not merely unusual for an artist still in her mid-fifties, but apparently unprecedented.

Although a celebration, these shows also had the feel of a disquisition or investigation: a 360-degree examination of her three-decades-long career, as well as an exploration of the genres of painting codified in the eighteenth century. At the Portrait Gallery, Dean showed portraits; at the National, she exhibited still lifes, both her own and works from other collections. Her Royal Academy show, which closed a few weeks ago, focused on landscapes. But Dean is not done quite yet. At the Fruitmarket Gallery in Edinburgh, she is currently offering a kind of coda—one last exhibition for now, which runs until the end of September. It seems to be the final piece of the puzzle, or—to put it another way—an attempt to break back out of the classical constraints of the previous shows.

The extravaganza has been all the more fascinating because Dean is by no means an easy artist to categorize. She is most often described as a filmmaker: indeed, films make up the bulk of her output, now more than sixty of them, nearly all shot on 16mm, a testament to Dean’s belief in the transcendent quality of analog over digital technology (she still does her editing by hand, slicing and splicing celluloid reels on an old-school Steenbeck flat-bed editor).

But the films, which range from a couple of minutes to nearly an hour in duration, have a quality that can only be described as painterly: long, contemplative takes; a rich color palette; a preternatural sensitivity to form and the play of light. And Dean also works in photography, sound, sculpture, and drawing, much of it underpinned and animated by an eloquent array of writings.

Much of her prolific output is delightfully difficult to pin down. One of her very first films, the black-and-white A Bag of Air (1995), portrays a three-minute journey in a hot-air balloon, but its main event is a pair of human hands waving a clear plastic bag from the balloon’s basket. It transpires that this is a latter-day reenactment of a medieval alchemist’s instructions on how to catch air at altitude, then distill “oil of gold” from it (the artist reads the recipe in a voiceover). It might also be a quiet joke about the challenges of making art.

Dean has a yen for quixotic quests. In one of the galleries at the Royal Academy, a vitrine was displayed, containing her extensive collection of many-leafed clovers, which the artist has been plucking since 1972 and carefully storing away. Symbols of luck and chance, they also play with what we think of as “landscape”: literally part of the natural world, they look profoundly unnatural when presented in the gallery. One of the artists whom Dean most admires is the Surrealist painter Paul Nash (1889–1946), whose own landscapes contort the British countryside into disconcerting, sometimes sinister forms. On the wall opposite Dean’s clovers hung one of Nash’s paintings, Cumulus Head (circa 1944), a cloudscape so abstractly sculptural it might be a slab of basalt, a drift of seaweed, or a thicket of cells multiplying beneath a microscope. Dean’s art has something of this quality, too: the longer you look, the more its shape begins to shift, and the more transcendent it seems.

In the next room at the RA was the artist’s most ambitious work to date—the hour-long film Antigone (2018), which was on show here for the first time. It, too, is a kind of distillation: Dean has been working on the piece for over twenty years, starting in a residency at the Sundance Film Festival in 1997. As she reveals in the catalog, its theme has occupied her for almost her entire life. Her sister is named Antigone, and Dean has long been fascinated by the story of Oedipus’s daughter, particularly in Sophocles’s version of the myth: the young woman who traveled with her blinded, ostracized father into exile, and who then defended her dead brother’s honor against the tyranny of the Greek state, eventually choosing to die for it.

Advertisement

Though landscape is a large component of the film, Antigone more closely resembled a history painting, shot in Dean’s customarily lustrous 35mm and displayed on two parallel screens. In this slow-moving, brooding meditation on Antigone’s story, the actual heroine makes no appearance whatsoever. A sun appears, and is eclipsed; a train rumbles over a bridge; Oedipus (played by the British actor Stephen Dillane) stumbles blindly across a desolate wilderness; geysers at Yellowstone seethe and bubble; Anne Carson reads from her poem “TV Men: Antigone (Scripts 1 and 2).” A little later, Dillane and Carson, this time out of character, engage in ruminative conversation about Antigone, in a courthouse at Thebes—Thebes, Illinois, that is, not Greece.

The light is burnished, but the mood is cool and the storyline fractured; even after repeated viewings, it was hard to say what Antigone added up to, other than a series of gorgeous vignettes. Once described by Dean as her “unmade work,” the film she couldn’t find a way to complete, it’s difficult to judge whether it is finished even now, or what being “finished” would mean. Perhaps that is the point: like a great deal of Dean’s work, it has an elemental quality, irreducible to anything other than itself. “The way we live, light and shadow are ironic,” reads a section of Carson’s poem, a grammatical riddle that appears to have no sure solution. That riddle is Dean’s, too: we admire the shifts of light and shadow, sun and cloud, but we are left uncertain what it portends.

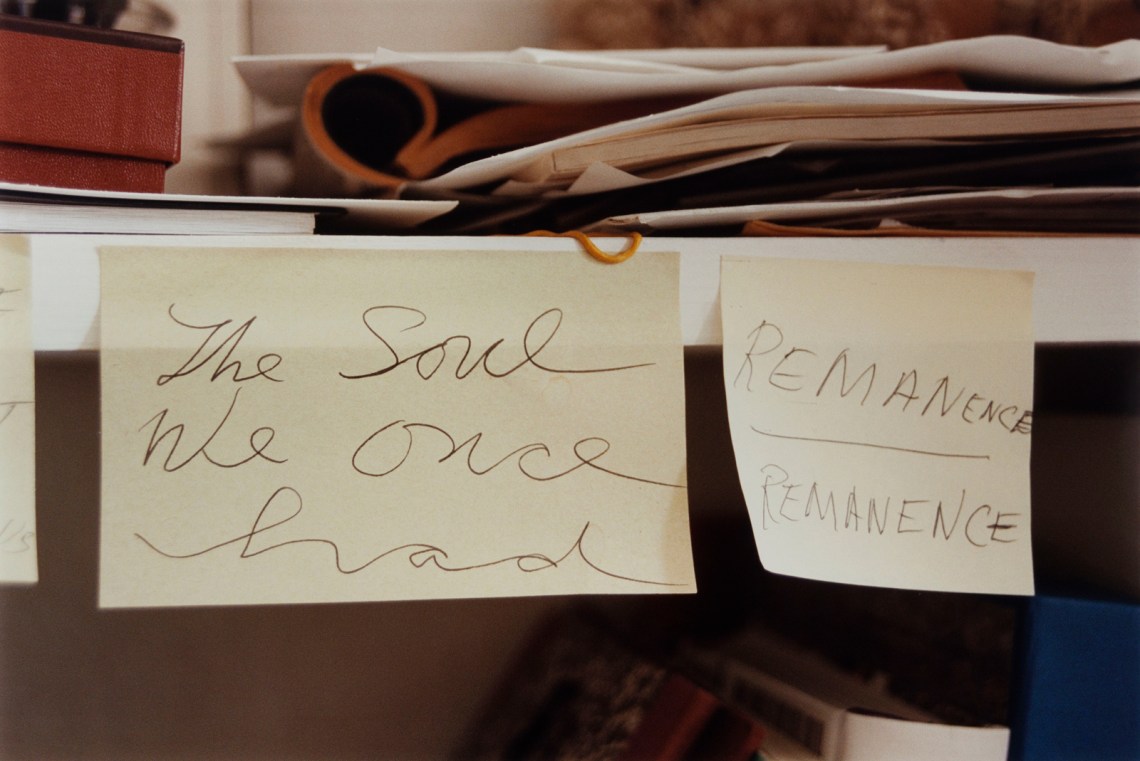

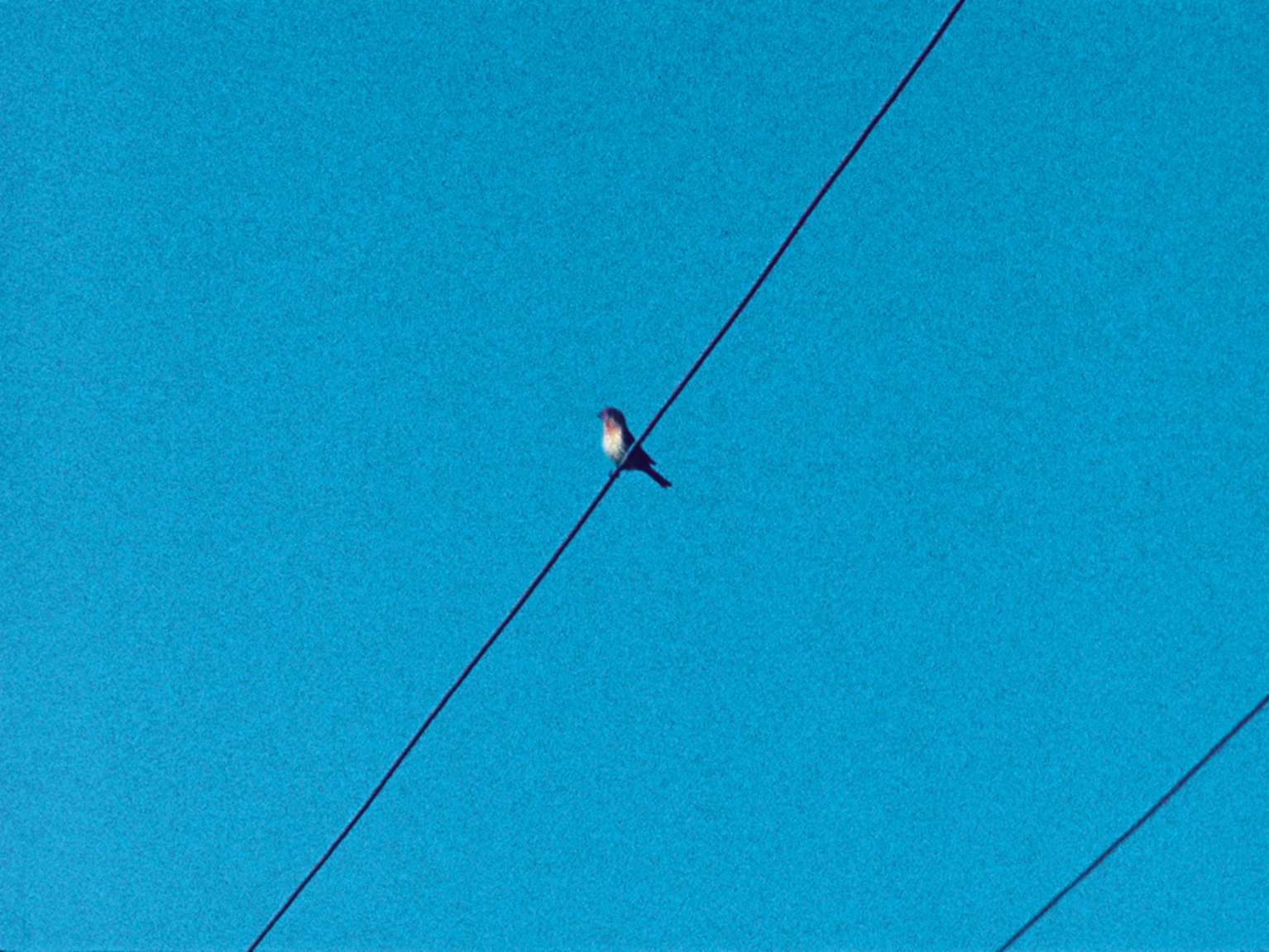

Perhaps this makes Dean’s art sound cryptic, or deliberately evasive, but for me the way it conjures magic from humdrum artifacts and chance encounters is its most moving and luminous aspect. A series of photographs on show at the National Portrait Gallery, entitled GAETA (fifty photographs plus one), was taken inside Cy Twombly’s studio on the west coast of Italy: it showed Post-It notes covered with Twombly’s cascading handwriting and a battered pairs of his shoes on patterned tile. Were these glimpses of artistic mortality, or of divinity? Perhaps both. At the National Gallery still-life exhibition, there was a three-minute film shot in LA, where Dean moved in 2014. Tiny in scale, projected high onto the wall, it depicted a bird standing on a cable against a blue sky. An act of quiet, rapt observation, it was not so much a still life as a life briefly stilled.

So astonishingly sensitive to shape and texture, Dean is not at her best, curiously, when humans enter the frame. “Living” film portraits of the actors David Warner and Ben Whishaw—Whishaw looking over a street; Warner pensive, shot in close-up, next to images of plants and bees—fail to penetrate the armor of these professional performers. A film of David Hockney, again shot in his studio, shows the artist coughing and kvetching and peering through his spectacles; it seems less a portrait than a caricature. Even Event for a Stage—Dean’s 2015, fifty-minute-long film, the centerpiece of the Edinburgh show—is, despite its ambition, something of a non-event: a semi-autobiographical account of Dillane’s battles with stage fright, interleaved with sections of the actor reading from The Tempest. A reflection on the dangerous uncertainties of live performance, it feels both muddied and obvious, as if Dean is adrift in a medium she doesn’t fully trust.

But in the next room at Edinburgh, the artist finds a way to say something fresh, even though the piece itself, Foley Artist (1996), is over two decades old. On one wall is light box displaying the dubbing chart for a movie, hand-written in pencil and more than thirteen feet wide: a kind of musical score, listing every sound effect required (“fire door slam” / “waves on beach” / “f/steps on carpet”), broken down into separate tracks and carefully matched to the visual action of the film. Every movie has a dubbing chart or cue sheet, listing both “canned” effects taken from tape and those recorded by Foley artists, who watch the movie on a soundstage and imitate the sounds required by the script.

In Edinburgh, the finished soundtrack plays out over loudspeakers—an abstract symphony of footsteps on wet sidewalk, occasional voices, and car doors clanging shut. Then, high on the other wall, you notice a small monitor: a film of the two Foley artists, Beryl Mortimer and Stan Fiferman, busily at work making all these sounds. Together, this odd couple, both veterans of the movie industry, clop across boards, rustle fabric, pretend-kiss, carefully close doors—all perfectly in sync with the noises we’re listening to, which sound bizarrely plausible. A piece of consummate, analog craft, both gently comical and quite sincere, it seems to say everything about Dean’s art and the handmade techniques that lie behind it. You don’t get magic, the artist seems to say, without plenty of realism.

Advertisement

“Woman with a Red Hat” is at the Fruitmarket Gallery through September 30.