At the entrance to the Met’s exhibition of mid-twentieth-century African-American photographs, a small placard politely asks for help: “Does someone look familiar? Please kindly send your suggestion.” A sense of loss shadows the request to identify the subjects. It is a reminder that these portraits were mislaid or discarded and eventually ended up at the Rose Bowl Flea Market in California and other resting places for the forgotten, where the Met’s buyers eventually found them. Though salvaged, the images remain tinted by this history, their anonymity like a kind of sepia.

Most people fade into oblivion over time, but African Americans have historically been robbed of the pride of being represented—with respect or sometimes at all. The Met show is clearly aware of its own part, as a cultural institution, in that wrong. There’s an undertone of apology in the exhibition’s introductory note, which acknowledges that the museum’s portraiture collection, dating back to photography’s beginnings in 1840, has included few images of African Americans until recently. The note informs us that the 150 studio portraits shown in the current exhibition were purchased in 2015 and 2017 as “part of an initiative, long overdue,” to correct that structural bias.

Despite this frame of regret and reparation, viewers at the Met when I was there were interacting with the photos with a sense of fun and recognition, pointing and laughing as if flipping through their own family albums. They recognized themselves in images of strangers, whose anonymity—at once a marker of loss—also created an opportunity for viewers to claim them as kin. Many people did look familiar—just not in the way the curators had hoped. The fedora worn by a man with a cross hanging from his waistcoat reminded one visitor of his father: “Daddy had a hat like that,” he told his companion. A woman with roots in Barbados and St. Vincent argued with her date over a face that seemed, to him, familiarly West Indian and to her, less so. The many images of World War II soldiers, aviators and sailors––alone or holding sweethearts or wives, pictured in front of palm trees, American flags, or idealized domestic backdrops––awakened for one visitor fond memories of her grandparents. They had exchanged photos to keep each other close during her grandfather’s service in the Korean War.

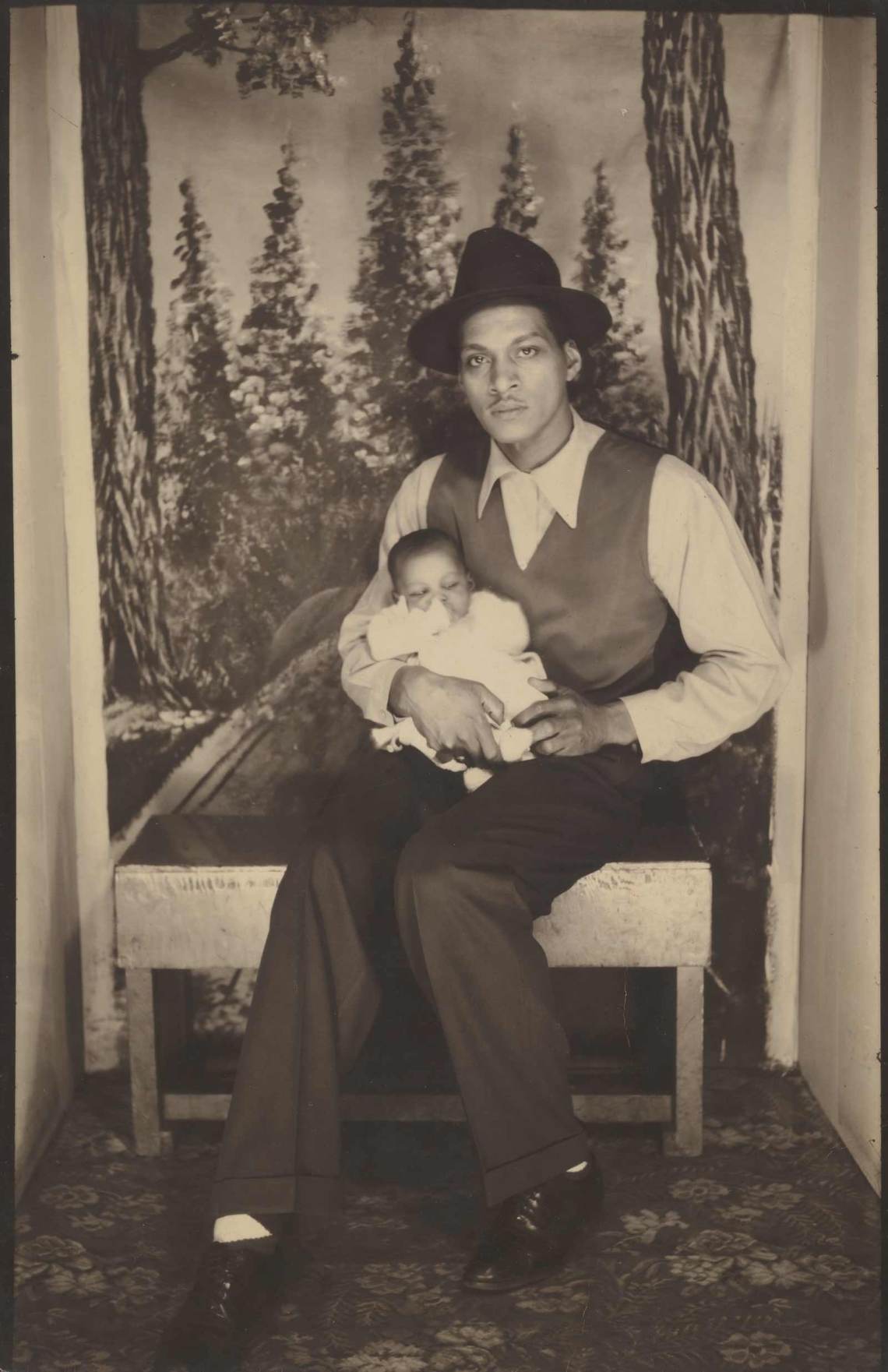

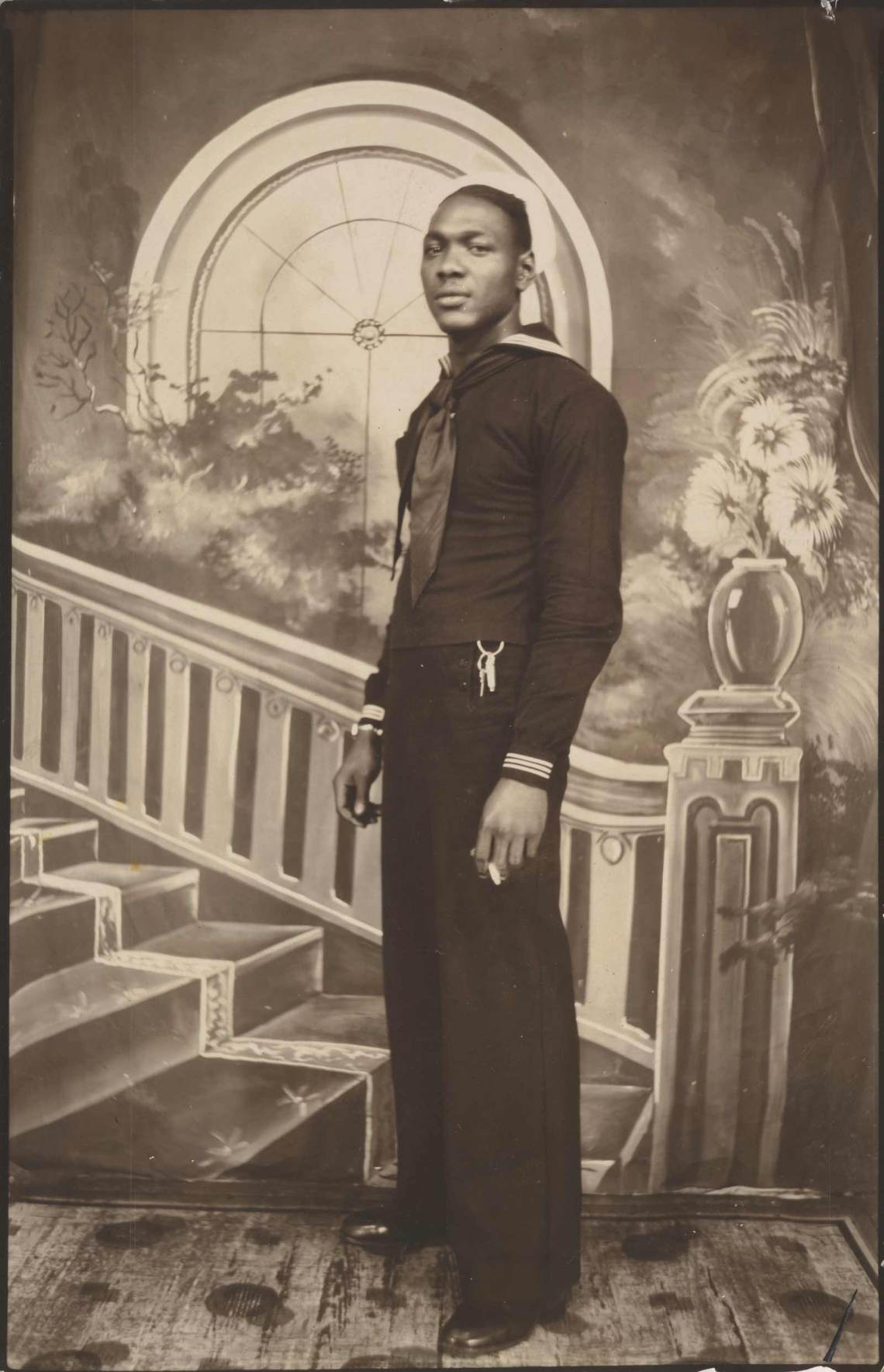

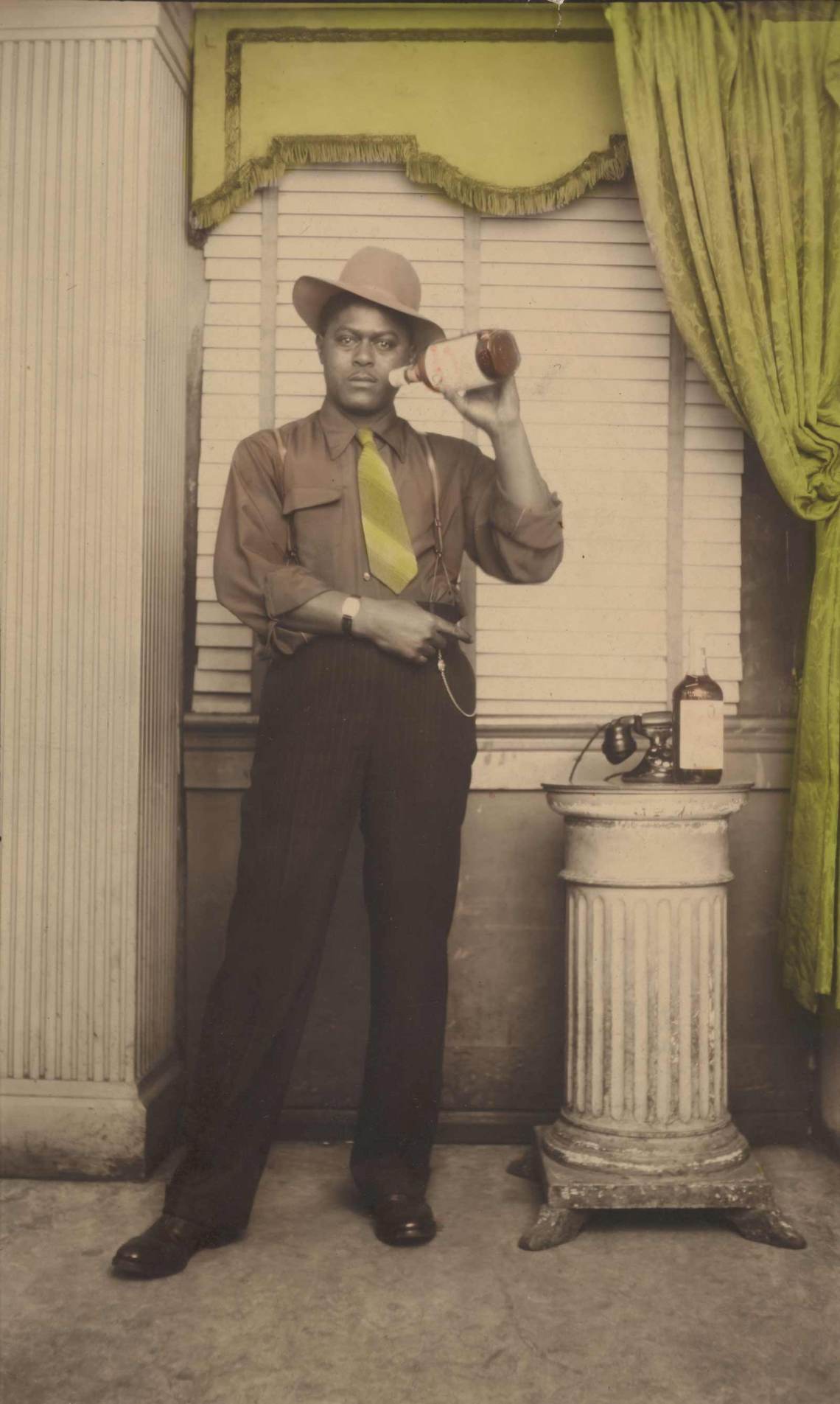

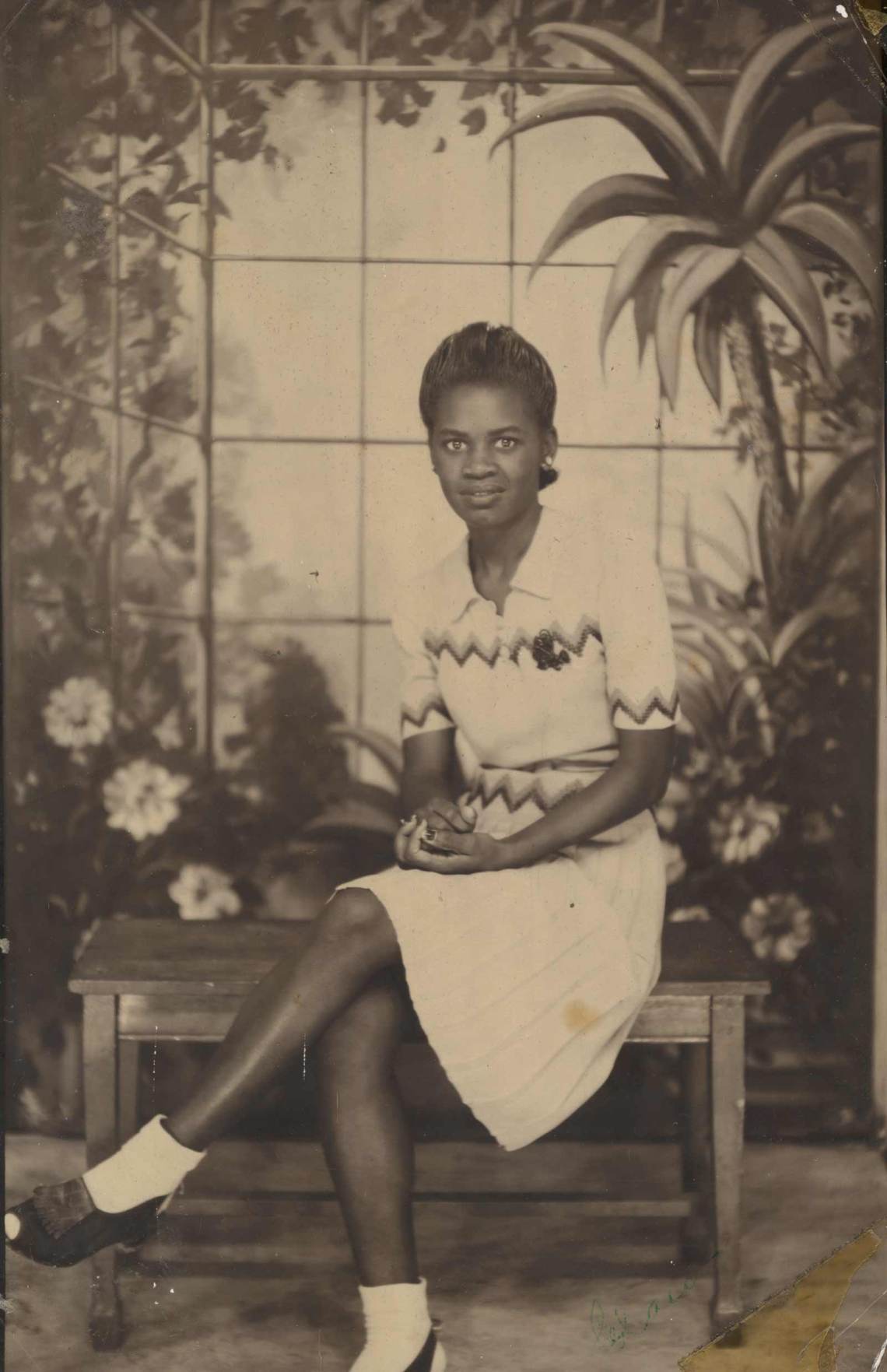

Taken during the 1940s and 1950s, at African-American-owned photo studios and segregated state fairs in the South and the Midwest, many of the photos create tableaux of respectability. Church hats, brooches, fur coats, pearls, ornate gloves, pinstriped and double-breasted suits, military uniforms, graduation caps and gowns, a veiled wedding dress, and evening gowns with corsages all confer a self-consciously upstanding quality to the men and women who wear them. Painted backdrops suggest success, even opulence: grand carpeted staircases, a banister crowned with a vase of flowers, offices with rotary-dial phones set on elegant stands, the odd veranda with a Doric column, lavishly draped picture windows, sylvan scenes set beside rivers or lakes spilling from them. Women adopt stylized poses, slightly angled, hands on hips to accentuate curves, and men stand jauntily with one leg perched on a bench in virile demonstration.

But not everyone is so formal in gesture, middle-class in style, or proper in demeanor. Two young men in jeans, one pair embroidered with Cupid-struck hearts above the pockets, wear energetic grins, their stances spread open. A sailor swallows in his embrace a leggy woman in shorts. A large-eyed little boy looks as if the camera interrupted some mischief. A man pretends to swig a bottle of liquor, a studio prop––a counterpoint to the playful woman sitting demurely cross-legged on a desk, cradling a phone to her ear.

The images were snapped with a bulky eight-pound camera called the PDQ (Photography Done Quickly), popular in arcades, amusement parks, and small town studios. The camera printed positive images directly onto rolls of super-speed paper rather than generating negatives on celluloid. Without the need to develop in a dark room, prints cut into a 2 ¼-by-3¼-inch format were ready within minutes. This method of “direct-positive printing” was so fast and affordable that photographers did a brisk trade, leading to shortages of the super-speed paper. The process, since it dispensed with negatives, led to some disorienting, funhouse-mirror effects: wedding rings on the wrong hand, the words “US Navy” reversed on a sailor’s cap. It also contributed significantly to the anonymity of those pictured. To allow for quick processing, the paper was coated, and this coating repelled inscriptions on both surfaces. Thus the exhibition presents a “Woman in Gingham Skirt, Seated” and “Man in Hat, Standing Beside Piano and Table,” the titles reflecting the bare details available in the images.

Advertisement

The few inscriptions that did somehow stick are touching evocations of the context of wartime separation. A man wearing a gold US Navy pin has written on the back of his portrait: “From Clem to my darling Edith.” A woman identified only as Beatrice has declared in a message in a looped cursive hand, presumably to an absent love: “I’ll never smile again.” On the verso of a brightly painted photo of an attractive young woman, hair done in a pompadour, delicate arms stretched out, are the words: “To Mr. James Jones from Mrs. Maude Jones. Remember always I love you.” Below, Mr. Jones has scribbled: “Sent to me in Sicily.” The curators speculate that he may have belonged to the Tuskegee Airmen, the segregated African-American unit that flew missions in Italy and North Africa during the war.

During another war, a century before the portraits in the exhibition were made, the abolitionist orator Frederick Douglass delivered several lectures on photography. Audiences were eager to hear him speak instead about the Civil War. A crowd at a Boston church was restive until he broke from his prepared remarks to speak directly about the evils of slavery. Douglass, thought to be the most photographed American in the nineteenth century, whose daguerreotype nestled in a gold-and-red-velvet case opens the show, was making a subtle argument. He held that “the soul might be described as a picture gallery,” and that human imagination might be influenced by images; internal change thus begins with external forms, colors, shapes. He believed that photographs had the radical potential to end slavery and uproot racism because they could change both how whites saw blacks and how blacks saw themselves. Owning your own portrait has value precisely because you possess the sight of others, their view of you. “Men of all conditions and classes can now see themselves as others see them and as they will be seen by those [who] shall come after them,” Douglass concluded.

Of course, the history of photography includes many examples of harmful, rather than empowering, effects for African Americans. Images of lynched blacks were widely distributed through postcards to provoke terror, even after African Americans served in World War I. In the late nineteenth century, naked profiles of African “specimens” were used in the field of scientific racism as evidence of their subhuman and inferior status.

Still, before and through the Civil War, free blacks like Douglass understood that daguerreotypes could be part of a profound process of self-fashioning for emancipated men and women. To have a fully realized interior life, a fleshy subjectivity, it was important for them to see themselves as bodies, as likenesses worthy of display as art rather than pseudoscience. A century later, the nameless African Americans in the exhibition similarly seem to possess a dignified recognition that they will be viewed by posterity. In all their posed finery, their aspirational Sunday bests, and their many expressions and moods, these subjects understood the importance of their own images. What they had, even if they or their descendants would not own the actual photographs, was an awareness of the sight of others trained on them, of their lasting presence.

“African American Portraits: Photographs from the 1940s and 1950s” is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through November 6.