Every year, it becomes clearer that New York is being reimagined as a city for the rich. Whether you celebrate or despair at this turn of events, this particular triumph doesn’t seem likely to have many exciting visuals. No elaborate Gilded Age mansions to gaze upon with envy—just bland, glass high-rise housing, some mix of luxury living, suburban shopping, and money laundering.

It makes the experience of an average commute both dull and tragic: a city without surprises, conspicuously lacking the public and private spaces that inspire and provoke new thoughts and experiences.

This state of architectural affairs is what makes MoMA’s current exhibition, “Bodys Isek Kingelez: City Dreams,” such a thrilling divergence. In the late 1970s, the Congolese sculptor Kingelez (1948-2015) began crafting what he called “extreme maquettes,” fantastical buildings constructed out of whatever he could get his hands on. He built most of his “extreme maquettes” in the city of his birth, Kinshasa, capital of the former Zaire, where he lived and worked as a teacher and museum conservator before becoming a full-time artist.

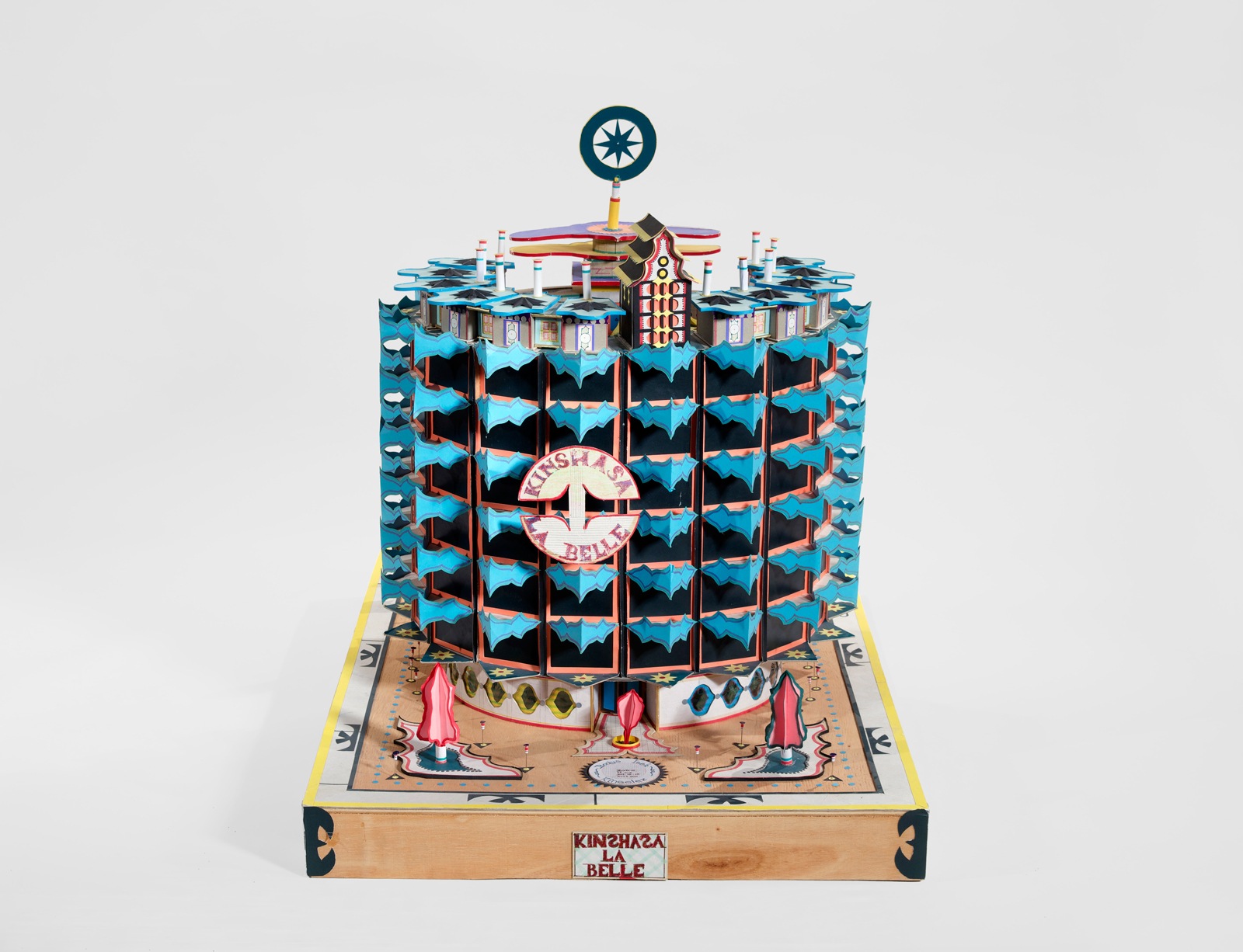

MoMA lists Kingelez’s materials (a small selection: paper, corrugated cardboard, styrofoam, bottle caps, paper and plastic straws, aluminum cans, map pins, metal grommets, ballpoint pen shafts) but notes that these are only the items that have been “definitively identified by conservators and curators thus far,” suggesting that there are further mysteries to his work. Out of these modest ingredients Kingelez creates a whole world, entirely his own.

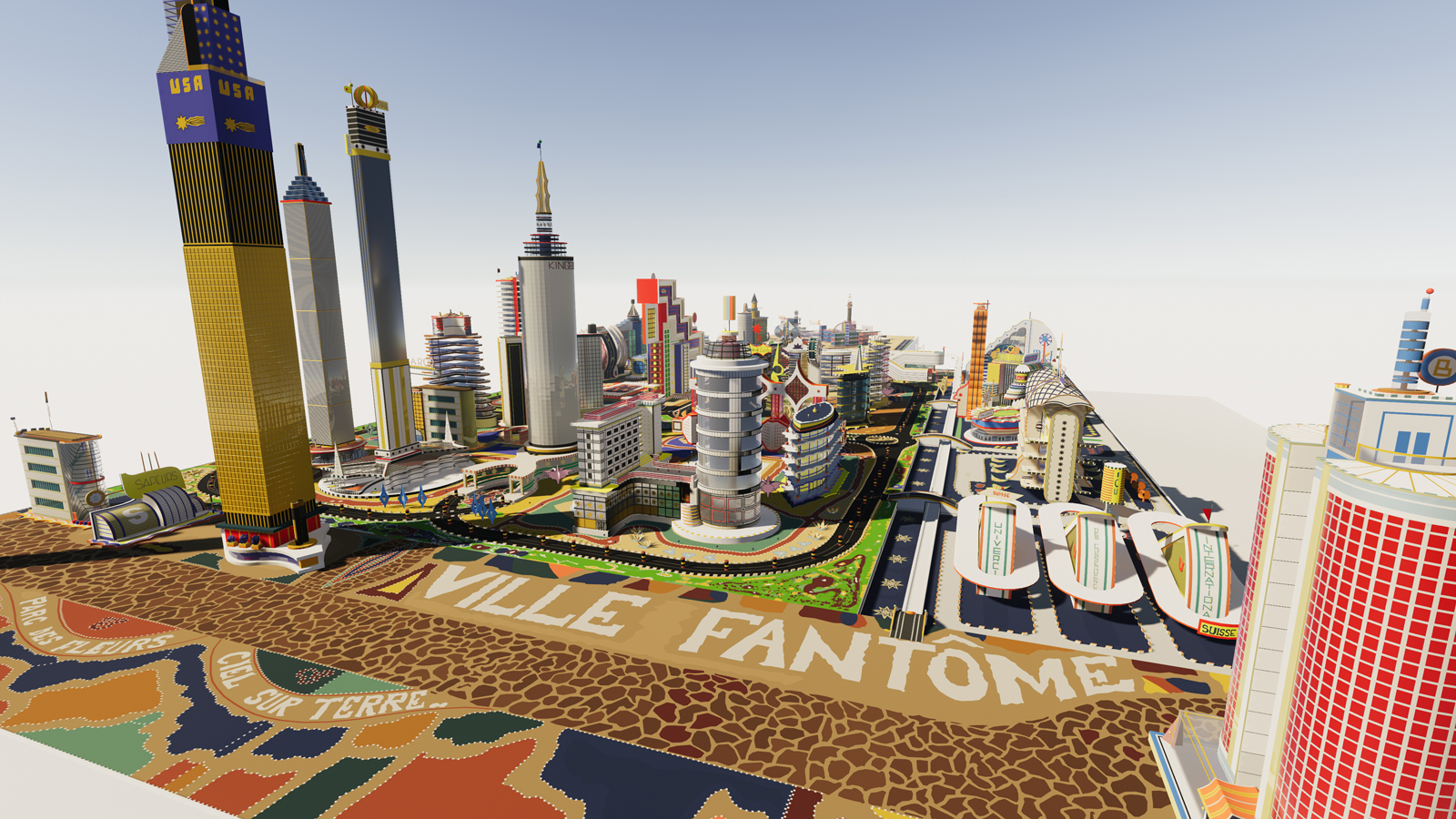

The sprawling, glittering future city of Ville de Sète 3009 is one example of an electrifying alternate civic space: a city made up of glittering skyscrapers that could easily have been crafted from stained glass. In addition to entire imaginary cities, this first full retrospective of Kingelez’s work offers an assemblage of eye-popping additions to any fantasy skyline: the awe-inspiring shark fin tower of Dorothe, the bright and inviting AIDS clinic The Scientific Center of Hospitalisation the SIDA. Each piece is riddled with decoration and ornamentation: bright pink foliage surrounding the circular tower of Kinshasa la Belle, the circles and stars that paper the Air Force building, and a color palette that always leans toward the bold and the vivid.

Peering down at Kingelez’s array of visions like some benevolent Godzilla, it’s an easy leap to imagine the lives of those living and working in a cityspace that instantly feels so exuberant, and so generous. None of Kingelez’s designs feature private residences, and he proclaims again and again that everything he designs is for the good of the people—of the world—explaining, simply, “I’m dreaming cities of peace.” What would it be like to live and work in a place that knows abundance and love the way Kingelez depicts it?

But reality punctures these reveries: some of the paper towers lean more than intended through age, and some of the buildings’ colors have faded.

It’s also hard to ignore the irony of an exhibition dedicated to such striking architecture being mounted at MoMA, the institution responsible for the destruction of its one-time neighboring building, then-home of the much-lauded Folk Art Museum, to make way for its own expansion in 2014. In the wake of the decision, one of the Folk Art Museum’s architects, Tod Williams, despaired at the lack of creativity in MoMA’s action, telling The New York Times that, “Yes, all buildings one day will turn to dust, but this building could have been reused. Unfortunately, the imagination and the will were not there.”

Kingelez’s own larger-than-life public persona and his championing of a greater civic life can seem somewhat performative. According to his friend and curator André Magnin, Kingelez lived a deeply private life: sequestered in a home surrounded by high walls, he refused to show his work to his neighbors or even his family, shrouding each maquette under a black cloth before its debut. “He was a visionary, and his work was a dream—his dream,” Magnin said. But he conceded, “I think he knew that they would never be built.”

It’s difficult not to hold onto Kingelez’s dream, despite the direction in which New York, and so many other global metropolises, are heading. It’s worth believing that fictional cities, however fantastical, can change the real ones.

“Bodys Isek Kingelez: City Dreams” is at MoMA through January 1.