Through his broadcasts over the course of forty years, Joe Frank, who died at seventy-nine this past January, brought the notion of the auteur to postwar American radio. He cleared a path for generations of producers who think of telling stories for radio not as a disposable information-delivery system for a mass audience, but rather as a place for ambiguous, strange artistic expression. Frank’s style earned him no more than a modest cult following. But his legacy lives on, in a very different form, in the work of Ira Glass (whose first job in public radio was as Frank’s production assistant) and in Glass’s own outsize influence on radio and now podcasting, where many of the best shows don’t aim to break news or provide trenchant analysis. Instead, they prize, above all, narrative tension and surprise, lending them an absorbing, binge-worthy quality that helps to build an emotional connection between the hosts and their listeners.

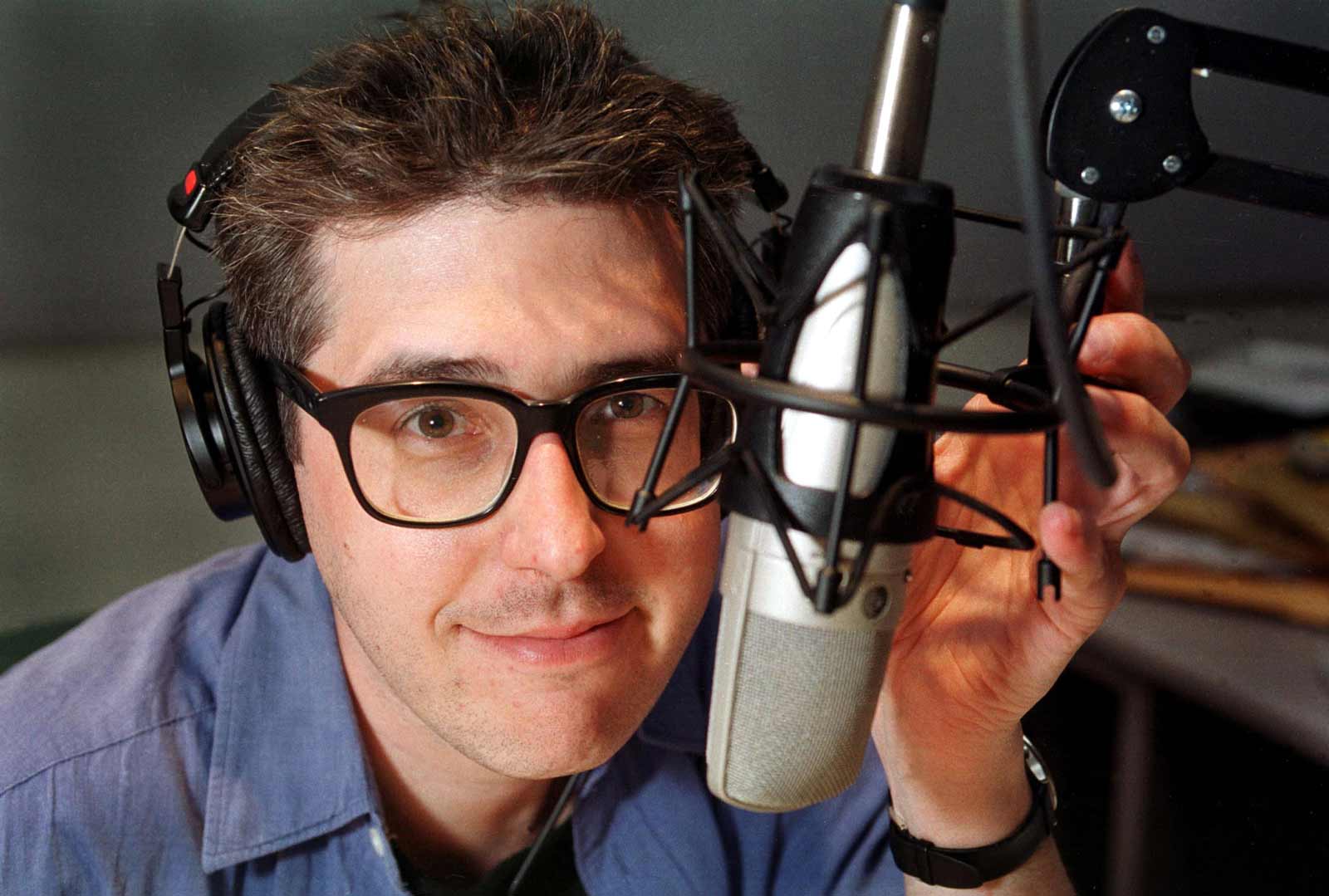

According to Glass, it was when he was watching Frank record a monologue in the studio in Washington, D.C. that he first realized that “radio was a place [where] you could tell a certain kind of story.” Frank gave him the desire to make this kind of story, by which Glass means an intimate, quasi-literary narrative, as opposed to a “straight” news report—although, Glass says, he decided to try to make this sort of radio narrative using just “facts and reporting,” rather than the blurred memoir and theatrical fiction that Frank dwelled in. Frank’s influence on Glass and others recalls the cliché about the Velvet Underground: not many people bought their records when they first came out, but everyone who did went on to start a band. This American Life’s success comes in part from its editorial emphasis on what marketers like to call “relatability.” This idea got Glass into trouble with the Internet a few years ago after he observed on Twitter that a performance of King Lear he’d attended in Central Park had “no stakes” and was “not relatable,” concluding, “I think I’m realizing: Shakespeare sucks.” Frank’s work, for all its willingness to provoke and confuse his listeners, still managed to have “stakes”; the major difference between Frank and Glass (and the rest of the journalistically oriented world of narrative audio) is less Frank’s use of fiction, or his idiosyncratic deployment of music, than his disinterest in Glassian relatability.

Frank’s work is, in fact, immensely “relatable”—if you’re disaffected and overcaffeinated and exhausted, driving alone on an empty freeway into Los Angeles in the middle of the night. But listening to his aggressively surreal and provocative work, it’s hard to imagine that he’d find a home on one of the major radio or podcast networks that bear his imprint today.

*

One of the strangest biographical details that recurred in Frank’s obituaries this year, usually mentioned in passing, was that, for a few months in 1978, he was the host of National Public Radio’s Weekend All Things Considered. This should be a highlight of any radio personality’s career: reaching a national audience in a position of great prominence and authority. But Frank’s work was dark, profane, sometimes perverse, and hilarious—words no one has ever used to describe any of the daily news shows on NPR (at least not since the first Gulf War, when it completed its transformation into a respectable mainstream news organization). The network began in the early 1970s amid the freewheeling, countercultural Zeitgeist reacting to the Vietnam War and Watergate. During Frank’s brief tenure as a host, he was himself in a countercultural struggle with Robert Siegel, who joined NPR in 1976 and went on to host All Things Considered for over thirty years, until his recent retirement. Siegel’s office was near Frank’s, and it was Siegel’s vision for the network to accomplish that aesthetic shift to the familiar, civil, straight-faced tones of today.

One of Frank’s first segments for All Things Considered aired on September 30, 1978. It begins with the host, Jackie Judd, introducing the segment in standard journalistic fashion, news peg and all:

The question of whether or not there is life after death was debated by scholars, scientists, and theologians at a conference in Innsbruck, Austria this week. Also at that conference were people who said they experienced the beginning of an afterlife in what they thought were their dying moments. NPR’s Joe Frank has some thoughts on the subject.

This introduction sets up a meditation on death that starts in a standard radio-commentator mode. Listeners can assume that next they will hear from an academic attending the conference, perhaps followed by a reported scene, and ending with some lofty reflections on death. “There’s no question but that most of us fear death,” Frank begins. “The thought of our own personal extinction through all eternity is terrifying… However, I have good news to report to you this evening.” He goes on to describe a “growing number” of reports by people who have had “out-of-body experiences, in which they felt themselves hover over their own bodies and over the doctors who tended to them.” Keeping up a news-host air, Frank expresses candid skepticism: “I would normally dismiss these accounts as completely delusionary, or even fraudulent, were it not for the experience of a friend of mine: ‘Caldwell.’” He says the name with arch quotation marks—and here, we begin to leave the realm of news commentary, entering another, stranger mode.

Advertisement

Frank relates the story of Caldwell, a “physical-fitness addict,” who decides to jog up the stairs to his apartment on the thirty-fourth floor of his high-rise building during the New York City blackout of 1977. His narration, now accompanied by sound effects—jogging steps, heavy breathing—pushes the story into the realm of fiction. The pacing feels wrong for an anecdote in a standard radio commentary piece; Frank’s voice takes on a slow-burning tone. There is an abundance of seemingly extraneous details about Caldwell—we hear, for example, a great deal about his various athletic pursuits. The narrative of his ascent up the stairs is meandering and has the interior quality of a novel.

Suddenly, Caldwell collapses in the stairwell and has an out-of-body experience. Frank describes him floating above the scene of his collapse, then moving through a tunnel into “a ballroom, decorated with bouquets of flowers, and paper-mâché streamers, balloons pressed against the ceiling.” We hear the music of a band playing in the ballroom, and the murmur of a crowd of revelers. Caldwell suddenly recognizes “the familiar faces of members of his family, now deceased.” With the band in full swing behind him, Frank describes this tableau of Caldwell’s dead relatives:

It was Jill, who died of liver disease, and his Uncle Harry, who’d passed away from gallbladder trouble, and his niece June, who’d drowned in the Potomac, and his grandparents and his great grandparents, and they were all around him hugging him and dancing and singing.

Frank’s narration pulls the audience out of waking life into a hallucinatory audio enactment of the afterlife. There is no narrative resolution, no final reflection on the nature of death, or on the meaning of the out-of-body experience (though Frank theatrically performs Caldwell’s response to being pulled back to reality with deadpan pathos, creating an effect that’s at once terrifying and hilarious, his trademark mixture). If the piece makes an argument at all, it’s an opaque and deeply pessimistic one: that the afterlife is entirely preferable to life. Or perhaps it can be heard as an allegory for the power of radio itself: as the listener, you’re transported into a dream, but the illusion is quickly shattered as you’re thrown back into your own life.

The announcement that follows Frank’s piece recalls the last page of William Gass’s experimental novella Willie Masters’ Lonesome Wife (published as a book in 1971, the same year as NPR’s first broadcast), in which we see, within the image of a ringed coffee stain, the printed motto: “YOU HAVE FALLEN INTO ART—RETURN TO LIFE.” What the announcer actually says is, “That essay was prepared by Joe Frank, who, starting tomorrow, takes over as a permanent host of the weekend edition of All Things Considered.”

*

So how, with Frank’s bizarre and unconventional approach to radio, did he become so influential? Beginning in 1976, he began producing monologues, improvised dramas, and stories for WBAI in New York, a Pacifica station that was at the heart of countercultural radio on the East Coast during the 1960s, with producers like Bob Fass and Jean Shepherd, who worked in a similar vein: digressive, comic, and philosophical radio essays that sometimes incorporated music, sound, and interviews but whose core was the voice—not of the interview subject, but of the host—unadorned, speaking into the air, looping back on itself, exploring ideas in conversation with itself.

Keith Talbot, a veteran producer with NPR from the 1970s, heard Joe Frank’s work on WBAI, and included a selection in one of his experimental hours for NPR, called “New York: the Grand Tour.” Deborah Amos and Jim Anderson, two of Talbot’s colleagues, fell in love with Frank’s work, and decided to bring him more prominently into the NPR fold. The only job available at the time, Talbot says, was as host of Weekend All Things Considered. Even in those looser, wilder days of NPR, Frank was an odd choice. Talbot said that Frank was miserable in the job, but he did get to do “these lovely little six-minute essays” at the end of each weekend.

Advertisement

Listening to the archives of those strange, early productions, though, one can begin to understand how Amos and Anderson thought that hiring Frank was a good idea. Alongside news reports and interviews, the network broadcast pieces that would be unthinkable on NPR today. At the end of its first week on the air, for example, the All Things Considered broadcast ended with its host, Robert Conley, introducing the final segment of the day. “At this point, we’d hoped to have a review of a play,” Conley begins,

but there aren’t many productions around Washington this week. Instead, by far the most impressive piece of dramatic pageantry that we’ve seen in some time occurred yesterday evening in the Western sky just before nightfall. In burning orange that changed to softer hues, the sun in all its majesty descended, attended by a company of clouds.

Which is to say, NPR will now cover the sunset. This introduction is followed by a conversation between voices that identify each other as an archangel and several clouds. They’re discussing the sunset they’re about to perform, scurrying and arguing like an amateur theater company (which the new staff of NPR in some ways resembled) moments before the curtain rises. A cloud interrupts, “Fifteen seconds, Archangel!” and, with two beats of booming timpani, the sunset begins. A new voice, different from those of the angels and clouds, begins to speak. It sounds as though it was recorded outdoors, with noises from wind and cars and birds surrounding it—a documentary field recording. The speaker sounds young, and his offhand, unscripted delivery stands in contrast to the stagy formality of the dialogue with the archangel. The voice describes the sunset, apparently in the sky before him as he speaks: “the orange and red mixed together makes it look crazy; you can’t miss it or look off or anything. It’s cool.” This must be the “student in Brockport” whom the archangel had described as one of the audience members who would be watching that evening.

“NPR was writing the rules as it went along when it started,” said Art Silverman, a senior producer for ATC who has worked for NPR for thirty-nine unbroken years. Robert Siegel began his career in radio covering the 1968 student demonstrations at Columbia for the university’s radio station, then working at two other New York City stations before joining NPR as a newscaster in 1976. But in those early days, most of NPR’s staff, Silverman told me, joined “because they liked playing with sound. They came not necessarily with a news background, but having been children of the kind of music productions that were taking place in the late Sixties and early Seventies.”

Keith Talbot was one such producer who cared more about sound and experimentation than news. Ira Glass, whom Talbot hired after Glass’s 1978 internship, said that Talbot’s job at NPR “was to invent new ways to do documentaries.” According to Talbot, it was the revolution in music production—in particular, the Beatles’ 1967 album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band—that influenced his approach to shaping the sound of early NPR. The important thing about Sgt. Pepper for Talbot wasn’t the way the songs themselves sounded, but how they were arranged and packaged on the album. “Before Sgt. Pepper,” Talbot told me,

The bands [of silence] between each song on a record were seven seconds long. On Sgt. Pepper they’re about two and a half, maybe three [seconds]. That was dramatic if you were a teenager [in the Sixties]. That made a big impact.

Each short song didn’t exist on its own, as it had on earlier pop albums, where each track appeared as a discrete product like individual sticks in a pack of gum. On Sgt. Pepper, the songs were in conversation with each other, flowing intentionally and impressionistically from one to another. The songs were conceptually linked, part of a larger, layered narrative—an album of real songs, performed by a real band that’s “dressed up” as the fictional Lonely Hearts Club Band.

Glass, who credits his time working under Talbot as “the reason why” he’s in radio, says that Talbot’s creative work centered around the transitions between stories within an hour-long broadcast: “One of the things that Keith was really interested in was inventing new ways to be the glue that would get you from place to place to place.”

One example of such “glue” exists in the two entirely fictional characters featured in Talbot’s “The PTA Variety Hour,” which ran on his experimental NPR series Options in 1979. The first is an unnamed man leafing through a catalog of school supplies. He’s daydreaming, and begins to imagine—inviting the listener to imagine—a PTA meeting. This fictional man begins describing this fictional PTA meeting, and as he does so, the sound of the meeting emerges, “out of radio nothing,” as Glass says. Thus, a secondary fiction emanates from the first. As the speaker brings up various subjects relating to education—computers in schools, students’ attitudes toward their teachers—the documentary segments finally emerge. After each journalistic story on education ends, we return again to the scene of the PTA speaker, who rambles on until she lands on another subject, which launches us into another piece on a different aspect of education.

Talbot’s justification for this radical approach to radio journalism, embedding documentary elements within imaginative structures, is that all radio—indeed, all media, even in the most traditional and conventional news forms—is already contrived. “It’s always fictional,” he said. “Because when you call it NBC Nightly News or All Things Considered or any brand—even Radio Unnameable,” Bob Fass’s show on WBAI whose time-slot Joe Frank inherited at the start of his radio career—“you’re tying the world up with a little fictional bow.” Why, Talbot’s work asks, is a straightforward news-magazine’s structure, like All Things Considered, which sets up segments and brings us authoritatively and logically from story to story, any less fictional than one in which we visit an imaginary PTA meeting, where the performative persona of the host is a fiction?

Talbot tells me that by producing stories—whether they take the form of a traditional news broadcast or an experimental radio fiction—program-makers are “abbreviating” reality. By creating these imaginative forms, Talbot hopes to awaken listeners to the ways in which all news is, in this sense, a manipulation of reality. “All of culture is packaging,” Talbot says. “And so what I did… is just make people a little bit more aware of that process.” This questioning of the ability of the news media to faithfully represent reality loses some of the self-reflexive charm it had in the Seventies now that the President works so strenuously to undermine the public’s trust in the press with his daily assaults on “fake news” to distract from the actual lies. But Keith Talbot says that the imaginative tools of narrative can be used for good or ill: “The difference between what I did and what the Russians did on Facebook last year, or what Donald Trump does every day,” he told me, “is intent. They create fictions with the intent of creating chaos. My intent was always to increase understanding.”

*

Frank, miserable in the job at ATC, left a few months after he started. He later told Salon, “the kinds of questions I was interested in, [All Things Considered] didn’t answer… Why are we here? What is the nature of God? If nature is bred with tooth and claw, is human compassion just an anomaly?” He became a regular contributor to NPR’s Options, an experimental show run by Talbot. During NPR’s budget crisis in 1983, Talbot and a number of other producers who represented the more creative side of NPR were laid off. By 1986, Frank had found a new home on the West Coast, at KCRW in Los Angeles, where he produced nearly two hundred radio programs until he was finally fired in 2002.

Freed from the confines of an increasingly staid national broadcaster, at KCRW Frank could create programs with far more narrative playfulness and impressionism than anything that made it onto the air at NPR, even in its most radical years. His later work pushed deeper into the ambiguous territory where fiction and essay meet: clearly fictional monologues would segue into excerpts (aired without permission) from tapes of the Buddhist teacher Jack Kornfield, which transitioned into authentic-sounding, though frequently staged, phone conversations (sometimes with actors, sometimes with friends and lovers) that laid bare raw emotion and intimacy. In a show from 1986 called “Let Me Not Dream,” Frank wakes up a series of his ex-girlfriends on the East Coast by calling them from the studio in LA and putting them live on the air, asking them to sing with him over an instrumental track of Vinson Hill and Rich Matteson Quartets’ “I Remember You.” All this material is connected by the hypnotic, looping instrumental soundtracks that did as much to link these disparate strands together as Frank’s narration did.

Frank spent hours searching for the perfect music to sample and loop for his shows. In 2013, he told the Believer, “If you took any of my radio shows and you took the music out of them, they wouldn’t be remotely the same thing.” Like Talbot’s sense of a radio program as a concept album, the music in Frank’s shows allowed radically disparate material to hang together and sit in conversation. He sampled from across genres: jazz, funk, rock, electronic, ambient, minimalist. The music loops he assembled tended to evoke a brooding miasma with bright little stings of pop or soul. In this way, the music resembled his stories: it cultivated an atmosphere of darkness, but that darkness wrestled playfully with the brighter moods that threatened to mar its totalizing bleakness.

Frank stayed at KCRW for sixteen years, until Ruth Seymour, the pioneering station manager who originally hired Frank—and championed his work for many years—fired him in 2002. (“Joe was feeling pressure to try to do a new show almost every week, so he ended up repeating and reusing material,” recalled a colleague. Another told me, “Joe wasn’t up to the task of putting out regular shows, mostly because he was in and out of the hospital at that time. He didn’t tell [Seymour] the details for fear of losing his spot, and she was angry to find out from someone else that he’d been hospitalized.”) A decade later, still battling a raft of illnesses, Frank returned to KCRW, then under new management, to contribute eleven new pieces to the anthology show UnFictional.

Frank had struggled with medical problems his entire life, enduring club feet, kidney failure, and several kinds of cancer. As Mark Oppenheimer reported in an exhaustive final profile in Slate, Frank was still working on a new story when he died from complications of colon cancer in January.

*

Frank showed producers like Ira Glass the possibility of radio as a narrative artform, but Glass adapted that lesson for the rest of the country. Nearly five million people listen to This American Life each week; at its peak, Frank’s shows reached a fraction of that number. But This American Life traffics in the audio equivalent of glossy longform magazine journalism, not Frank’s uncategorizable radio autofiction.

Podcasting emerged from the geekier corners of the Internet into the mainstream in large part thanks to the success of Serial, the true-crime podcast that Glass’s team launched in 2014 with host Sarah Koenig. And today, podcasting is awash in money. Corporate sponsors like Goldman Sachs and Uber—along with investments from venture capitalists—provide new shows with six-figure budgets, and production companies are increasingly flinging money at podcasts to purchase intellectual property that it can spin into new streaming TV series. Perhaps as a result of this commercial explosion, most narrative podcasts hew more closely to the This American Life end of the spectrum. The Internet and tech culture show Reply All, which was launched under the editorial supervision of Alex Blumberg, another disciple of Glass’s, seems to take pleasure in abandoning its ostensible tech beat whenever it suits its producers, who pursue an omnivorous approach to nonfiction audio storytelling. Reply All delights in pulling its listeners through dizzying sequences of narrative frames that recall Frank’s nested-story experiments, although they still land firmly on the side of explaining where you’re going and what’s happening. (It’s difficult to imagine Squarespace or Google buying regular ad spots if it did otherwise.)

So where, ultimately, can we detect Joe Frank’s legacy? Can his DNA be found in the clear and enthusiastically relatable work of Ira Glass and his new-new-journalistic offspring? Or only among the experimentalists working at the noncommercial fringes of the corporate-sponsored podcast boom? If This American Life and shows like it can sound formulaic, it’s because Glass developed a supreme narrative formula. As he describes it, a TAL story is simply a series of anecdotes followed by a moment of reflection. And that’s an incredibly effective way to tell a story.

But is it present in Joe Frank’s associative and ambiguous body of work? Frank’s stories are suffused with anecdotes, with series of events, and he’s nothing if not reflective, drawing out the everyday dramatic ironies and cruel, universal indignities of being a human with a body in a culture governed by desire, fear, and shame. Even Frank’s work, in all its wild unpredictability, followed a formula: mix together a few repeating elements—surreal fictional monologue; loosely autobiographical improvised dialogue with actors; and a few bars of instrumental Krautrock looped to the horizon—and voilà: radio literature. But perhaps it’s unfair to call this, or even Glass’s narrative strategy, a formula. It’s more like a framework for these hosts to work within.

Joe Frank’s legacy isn’t in his specific approach to storytelling, or his aesthetic, or even his use of music. It’s in his approach to radio itself, the sense of radio not as a medium of mass communication, a place for traffic reports and newscasts, but rather as a site for artistic expression as fertile as the canvas or page. The producer Jonathan Goldstein, whose latest show, Heavyweight, is on the same podcast network, Gimlet, as Reply All, is among the clearest descendants of Joe Frank, with his delight in non-sequitur and his willingness to explore and explode his own life for the sake of making interesting stories. In an interview a few years before Frank’s death, Goldstein asked Frank if there were any “radio people” whom he emulated. Frank dismissed the idea out of hand, but then allowed that, rather than radio, it was books that influenced him. “I might have resembled some of the people I was reading,” he said—stories of alienation by Dostoyevsky and Kafka. It’s a lesson that French filmmakers learned in the 1950s and 1960s with the emergence of auteur theory, the idea that the most talented directors are able to express a singular authorial vision despite the collaborative, expensive, electrified machinery of movie-making. And its application to radio was proposed by the Australian scholar Virginia Madsen. Of the new wave of radio documentarians that emerged in Europe in the 1960s, Madsen wrote, “Why not a radio d’auteur, just as we say a film d’auteur?” Joe Frank’s voice, and the stories he tells, are clear and engaging—even as he seems to alienate his listeners, maintaining a sense of profound weirdness and ambiguity. He showed that radio could succeed even by leaving its listeners in the dark—as long as it joined them there.