In 1963, in his lecture “The Artist’s Struggle for Integrity,” James Baldwin reflected on the way that artists—more than anyone—can tell the truth about what it means to survive in the world. “[O]nly an artist can tell,” he said, “and only artists have told since we heard of [humankind], what it is like for anyone who gets to this planet to survive it.” Perhaps appositely, two years later, in his momentous debate with the conservative intellectual William F. Buckley at Cambridge, Massachusetts, Baldwin shared another truth, this one a painful, formative epiphany that defined his time on this planet. “It comes as a great surprise,” he said early in the event, “around the age of five, or six, or seven, to discover that the flag to which you have pledged allegiance, along with everybody else, has not pledged allegiance to you.”

Baldwin knew what this betrayal felt like on multiple levels: as a black American, as a gay man. I understand this betrayal of a flag, too, this way that you can live in a country and have the profoundest sense that it wishes you did not live there, that it even wishes, perhaps, you lived in the “undiscovered country,” where no one lives at all. I know it as a person of color, as a woman, as someone who grew up in another country, and, above all, as a transgender person in a moment when I am told—casually, by a leaked memo, which says that the Trump administration wants to create a legal definition of sex as, according to The New York Times, “a biological, immutable condition determined by genitalia at birth”—that our government believes people like me should not exist. That we are what we are assigned at birth—male or female, as defined solely by our genitals—and that we cannot have a discordant sense of our gender, cannot be intersex, cannot, in other words, be anything beyond a simplistic, fixed binary. The ignorance and ignominy of all this hurts—but it is a pain I am accustomed to, since one cannot live as a trans person in this world without learning to endure many shades of anguish.

The memo presents the dubious, dehumanizing argument that sex and gender are equivalent, which they are not. Every human has a gender identity; transgender people simply are aware of it more acutely because our sense of who we are comes into conflict with our bodies or with what we are called, what roles we are expected to fulfill, how others perceive us.

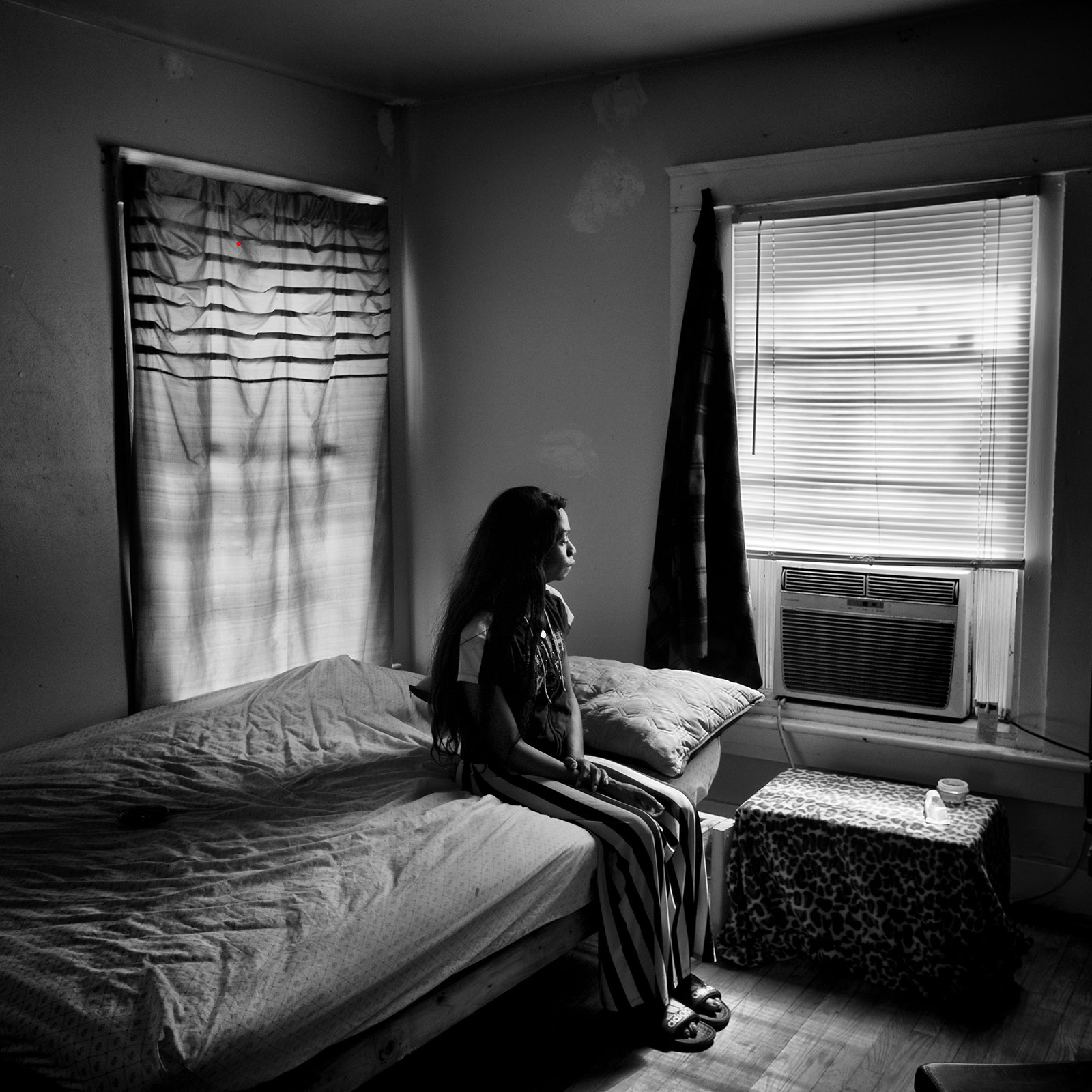

It is not just humiliating to imagine having to change the “F” I worked hard to get on my identification documents back to an “M”; it is also dangerous, if the wrong people, requesting my ID, decide that the woman before them has somehow deceived them and thus must be punished, pushed aside, pulverized. I am a woman; I have always felt this, as though a light switch set to girl in my head has always been on. Transitioning helped me feel more at home in my own body; it helped my sense of self feel less claustrophobic, helped me hear less of the blue music that would play, on interminable repeat, when I was depressed.

Transitioning, honestly, saved my life. I did not transition on a whim; I had to give up living in the Caribbean island where I had grown up in order to transition, as my home did not accept queer people of any kind. I did not choose the years of agony of living in a cramped closet. And I am not hurting anyone by being myself; if anything, I am helping others like me see that they, too, can be who they are. Only someone bereft of empathy would contemplate barring me from my right to be who I am.

But this is not an administration known for its empathy. The proposed erasure of trans people is a colossal invasion of privacy, all the more egregious for a party that touts the virtues of small government and the sovereignty of the individual. The move claims to be rooted in science, yet science contradicts the memo’s claims; in any case, the Trump administration has shown scant regard for scientific evidence in general, most notably in its repeated refusals to accept the reality of climate change.

To be sure, this is likely all about scapegoating. I am not one for conspiracy theories; all the same, it is hard to believe this memo was not leaked intentionally as a last-ditch effort to shore up conservative support and staunch the projected gains of Democrats in the midterm elections. When this administration desires a quick burst of support from its most ardent advocates, particularly its anti-LGBTQ evangelical base, it trots out transphobia; this, after all, was why, in June 2017, President Trump peremptorily announced the ban on transgender people serving in the military (a measure as yet blocked by court order). Then, as now, it was a cruel attack that came, seemingly, out of nowhere (although the administration had been slowly working to roll back Obama-era guidance on how transgender students should be treated in schools). The still very significant hostility directed at transgender people means that we can be used as a convenient political tool: if the right wishes to divert attention from any failure or scandal of its own making, all it needs is a quick resort to anti-transgender propaganda.

Advertisement

I am tired of being a scapegoat, tired of being burned in effigy over and over—and tired of fearing that one day, I may be burned or beaten in a much more literal way, should a violent person decide that I should not be allowed to use the women’s restroom, or that I should not teach their kids, or that I should not speak up at all. Still, I refuse to become an invisible woman, hiding away, like the protagonist of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, in some underground refuge—even if, in my weaker moments, when I get tired of being so despised simply for existing, I sometimes wish I could indeed become ghost for a while, body and blood and earth discarded, and vanish away.

*

Desire—in particular, a yearning to be who we are and love freely—is a strange lantern: it wants to be lit bright, but sometimes, to do so is deadly. In the early decades of the twentieth century and up until the twenty-first, some queer writers let that flame burn for all to see, but many more only gave us flickering glimpses of their desires, will-o’-the-wisps to follow through careful, scholarly reading. We need to speak out now, more than ever—and we need to do so in ways both loud and quiet. There is a special power to revealing our desires quietly, yet brightly, on the page or screen.

This is why I find myself reading Amy Lowell’s poems so fondly; unlike some queer poets of the early twentieth century, Lowell wrote with surprising directness about desire, in particular her desire for other women. In contrast to a more private woman-loving female poet like Elizabeth Bishop, Lowell expressed her queer love almost nakedly on the page. Though Lowell knew she could reveal only so much without repercussions—she was treading dangerously enough by living in a so-called “Boston marriage” with her partner of many years, Ada Dwyer Russell—she still could write passionately about women, as in “The Blue Scarf,” in which she described how “[t]he scent of her lingers and drugs me” and “[h]er kisses are sharp buds of fire; and I burn back against her.” It makes me feel a little shudder at its loveliness, but also at the way that, a century later, there is still a courageous resistance in being open about who we are and whom we love (or do not love).

When I first read Janet Mock’s affecting 2014 memoir of coming out as trans, Redefining Realness, I felt a similar frisson. Here was a story about someone like me, told directly, with striking candor, and defiant in its proclamations about both the pains and pleasures of transitioning. Mock’s book was one of the first works I read by an openly trans writer, and it opened my world. That she had also had to navigate the world as a curly-haired, nonwhite woman made Redefining Realness feel all the more essential.

For the poet Kokumo—black, trans, intersex, femme—art works when it is true. “Sometimes the honesty is loud,” she told the nonbinary poet and activist Noa/h Fields in 2017. “Sometimes the honesty has to be heard. Sometimes the honesty can’t sit quiet.” We have more queer narratives than ever, but we always need more; there are still many people who have no idea what it means to be a trans person (be they binary or non-binary), or to be intersex or asexual or aromantic, no idea that, in other words, a liberated identity resists simple, unchanging binaries—as it should, because the multifariousness of identity mirrors the lovely and curious complexity of life.

We have to fight, so that no administration tries to redefine our reality for unearned political points—not just for trans people, but for anyone who has been marginalized. We need, more than ever, stories of what it is like to be us; we cannot be erased if our stories remain. We need to resist, on and off the page, so that, like Baldwin, we survive, and so that we find a way to keep our lanterns lit, just a little longer, illuming both the beauty of our identities and our paths forward.

Advertisement