In the early 1980s, when I was an editor at Condé Nast’s House & Garden magazine, my colleagues and I were perturbed by an idée fixe of the company’s legendary editorial director, Alexander Liberman. He kept pressing us to make House & Garden more like Architectural Digest, the Los Angeles-based upstart that, under the editorship of Paige Rense, was fast approaching our once-impregnable circulation figures. He must be going gaga, we thought, as we contemplated the flashy, vulgar interiors in that veritable bible of bad taste, which we called Architectural Disgust.

Alex parried our prissy objections with a Machiavellian riposte. “Architectural Digest,” he assured us, “has the hideousness that will attract.” In retrospect, I have never heard a better definition of nouveau riche American aspirations. But nothing we tried could stem our declining newsstand sales and subscription renewal rates, and in 1983 House & Garden was relaunched to take on AD, as it was familiarly known, and we took on the challenge of producing what we believed to be a better version of that Beast of Beverly Hills.

To cut a long (and very expensive) story short: it didn’t work. As a commercial proposition—which was all that mattered to S.I. Newhouse Jr., or “Si,” Condé Nast’s gnomic board chairman, a true Sphinx without a secret—we could never reverse the conviction among advertisers that AD was the product and we were the competition. “If Si likes Digest so much,” I expostulated after one frustrating editorial meeting, “why doesn’t he just buy the damn thing?” Which is precisely what he did in 1993, keeping Rense on as editor, and immediately closed House & Garden. Although Newhouse revived that magazine three years later, Rense would brook no opposition, and at a New York dinner soon after bragged, “I killed it once, I’ll kill it again.” Her malediction came to pass in 2007, when Newhouse terminated that 106-year-old American institution permanently.

But Si had apprehended the seismic shift then afoot in the upper-income levels of American taste—away from the discreet cultivation of East Coast grandees like the Rockefellers and Mellons (which I’ve called stealth wealth), and toward the unabashed display of new money that characterized the Reagan Revolution, especially on the West Coast and across the Sun Belt, where the operative attitude was “If you’ve got it, flaunt it.” And no magazine reflected that change more accurately than Architectural Digest.

As she approaches her ninetieth birthday next May, Rense—who in 2010 was eased out of her powerful position after four decades as AD’s figures sagged and her then-dated formula became the Madame Tussauds of decorating—takes a stroll down memory lane in a gaudy new compendium, Architectural Digest: Autobiography of a Magazine 1920–2010. Given the relentlessly first-person focus of her otherwise rambling and disorganized text, it might be more accurately subtitled Autobiography of a Magazine Editor. But to the extent that AD was always Paige Rense and Paige Rense was always AD, no further distinction need be made.

Her rags-to-riches life story, which she touches on only fleetingly in the book, recalls the clichéd scenario of a Joan Crawford “women’s weepie” movie from the 1940s. The bootstrapping nature of Rense’s career rise perhaps explains her reported ruthlessness in a climb to the top of the glossy magazine world. In a classic 1990 New York Times Magazine profile, Joan Kron revealed that Rense had routinely shaved four years off her age and was actually born in 1929, to an Iowa woman who soon gave her up for adoption to a Des Moines couple. They renamed her Patricia Louise Pashong. Her new father was a school janitor and his wife, according to Rense, “was a functioning retarded person. She did her best. My adoptive father made our lives a living hell.”

By 1940, the Pashongs had moved to Los Angeles, where Patty Lou flew the coop at fifteen. The unhappy girl dropped out of the ninth grade at Hollywood High—the extent of her formal education, though she later lied about having a bachelor’s degree—and worked, she said, as “an usherette at every theater on Hollywood Boulevard.” After trying out various new first names, she settled on Paige, married and divorced twice, and worked at a variety of jobs.

In 1955, she landed an editorial position at Water World, an LA-based skin-diving magazine. Two years later, its managing editor, Arthur Rense—whom she’s called “my university” for broadening her worldview—became her third husband and then her fourth, fourteen years after they divorced; and she forged ahead with Rense as her surname. He was a sportswriter and an amateur poet, and after his death in 1990, she endowed the Arthur Rense Prize for poetry, a $20,000 award given triennially by the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Her fifth husband was the painter Kenneth Noland, whose colorfield canvases featured prominently in AD before and after they married in 1994; she was widowed again in 2010, and socially now goes by Paige Rense Noland.

Advertisement

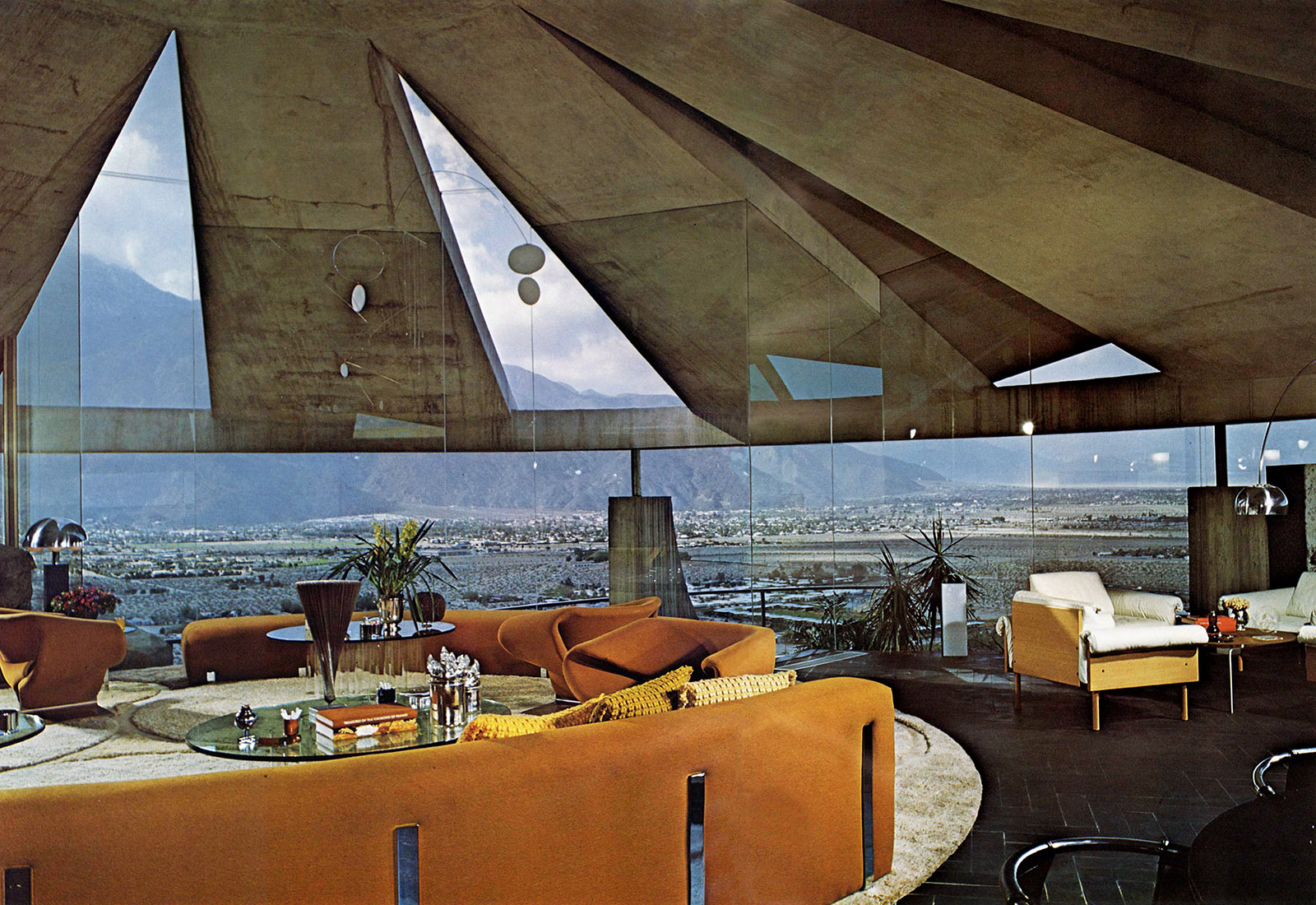

Rense’s professional ascendance was no less remarkable than her upwardly mobile personal history, and her big break had a noirish twist worthy of Raymond Chandler. In 1971, six months after she joined the four-person editorial staff of Architectural Digest—a cut-rate monthly aimed at the Southern California building industry—the magazine’s editor-in-chief was murdered in a nighttime street robbery and she was suddenly promoted to take his place. Over the next decade, Rense transformed the amateurish trade journal into a prescient bellwether of the conspicuous consumption that would typify the ensuing Reagan years.

AD’s Californian orientation had much to do with its success. Snobbish New Yorkers may have snickered at the glitziness Rense favored, but the rest of America lapped it up. It showcased decorators we at House & Garden had never heard of (Melvin Dwork, Sally Sirkin Lewis, Jay Spectre); pop celebrities we disdained (especially Cher, who repeatedly put her houses up for sale soon after they were shown in AD); and photographers whose techniques we thought cheesy (including Jaime Ardiles-Arce, whose purple-washed images always seemed to be shot from behind a potted palm).

Then there was the piss-elegant Paige-speak of AD’s prose style, in which chairs “attended” tables, rooms “boasted” chandeliers, and houses “sported” wide verandahs—a comprehensive glossary of pompous locutions. (Some of that hoity-toity terminology persists in her new book, where it contrasts jarringly with her tough-gal first-person voice.) But as did that other astute judge of tacky American taste, Liberace, Rense cried all the way to the bank.

Love it or loathe it, her approach conveyed an impressively unified vision and it did indeed make AD’s parent company, Knapp Communications, pots of money. This Rense accomplished in part by dispensing with costly niceties such as sending journalists to visit the places they wrote about. Instead, they had to work from slides and hoped to get their facts straight. Whereas House & Garden would routinely fly at least five people to a photo shoot and spend thousands on plane tickets, hotels, meals, as well as flowers to prop the interiors, Rense alone visited the projects she featured. Photography in AD for many years was paid for by the designers themselves, though restricted to photographers of her choice.

Another weapon in Rense’s armory was her strict enforcement of exclusivity. She demanded not only that decorators who appeared in AD give her right of first refusal to their future work, but also that they would withhold it from rival publications even if she turned it down. To cross her even once—stories of her vindictiveness ricocheted around the design world—was to be banned for life from what had become the hottest shelter magazine of the late twentieth century. Few dared do so. Rense—as Oscar Levant once said of Debbie Reynolds—is “as wistful as an iron foundry.”

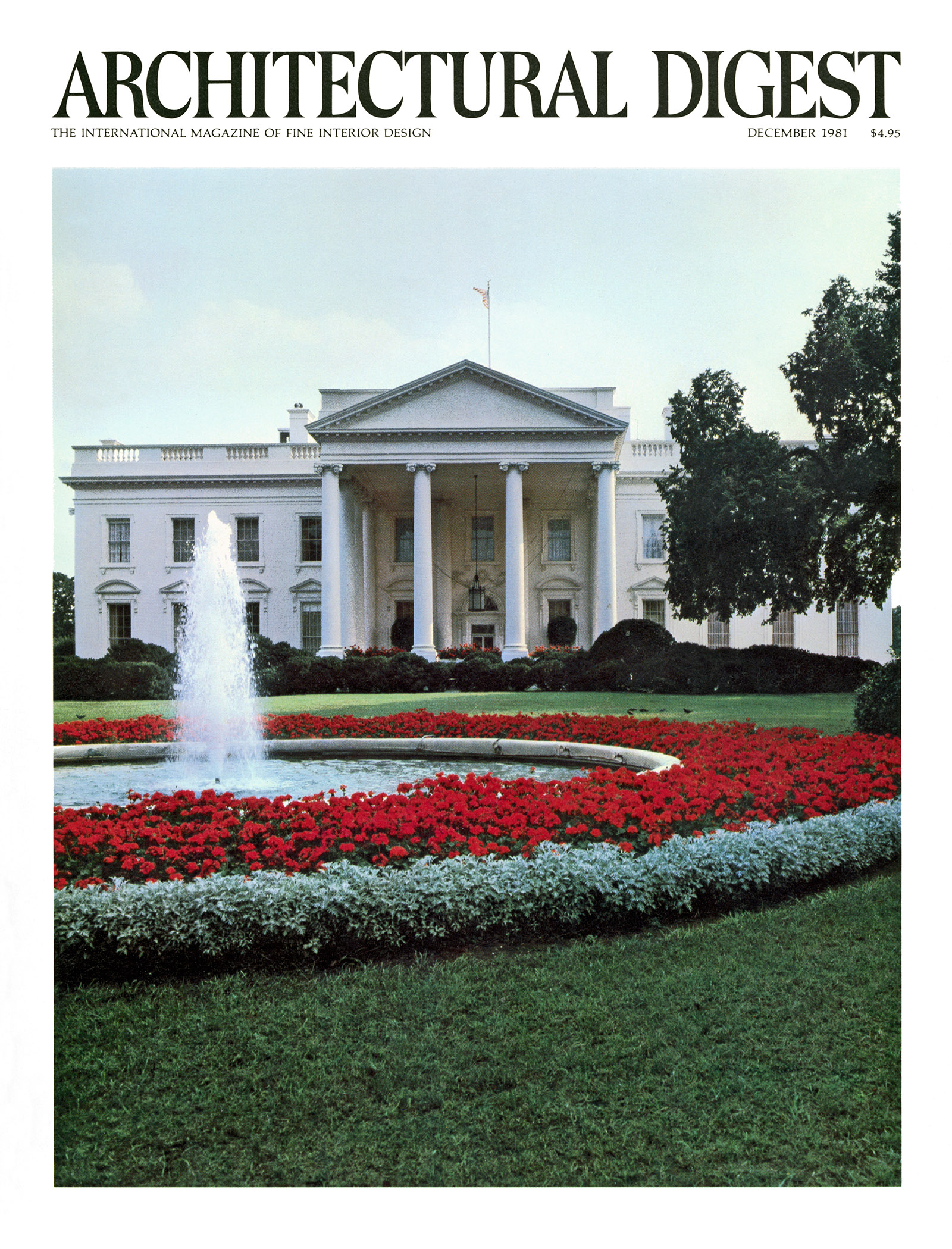

In 1981, Rense pushed the boundaries of that policy when she scored a publicity coup by securing the rights to publish pictures of the private family quarters of the White House, which had been redone after Ronald Reagan’s inauguration. The story appeared as AD’s cover that December, and even newspapers had to credit the magazine for the few images that were grudgingly released. It is one thing to exact a non-compete clause when a private property is involved, but to impose exclusive rights over a house owned by the American people caused outrage in the publishing world. (Although I’ve never met Rense, I’m sure I’ve been on her enemies’ list ever since I wrote “Upstairs with Nancy and Ronnie” for the March 1982 issue of the architectural paper Skyline, a snarky account of the Reagans’ “Louis Schmooey” gilded décor and AD’s swooning coverage.)

Rense had an inside track in getting the story because of her longstanding relationship with the Reagans’ decorator, Ted Graber, an LA designer who worked for several friends in the Reagans’ West Coast circle of Annenbergs and Bloomingdales, but who was considered hopelessly provincial among the First Lady’s new East Coast coterie. But as Rense understood, you don’t have to like something you are curious to see, a point that we at House & Garden never acknowledged, to our peril.

In addition to Graber’s work—which came to $822,641, covered by private donations solicited to supplement a small congressional allotment—I was particularly critical of the fact that Nancy Reagan also commissioned a new state dinner service of garish red-and-gold Lenox porcelain, which cost $209,508, an ill-timed purchase while her husband’s administration cut funding for school-lunch programs and infamously insisted that ketchup was a vegetable. Marie-Antoinette was invoked more than once in mainstream press coverage of this unseemly spending spree. In contrast, the Reagans’ parsimonious predecessors, Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter, made do with the existing White House décor. Probably their biggest expenditure was to install solar panels on the roof, which their successors promptly had removed.

Advertisement

When The Washington Post reported that the tab for the china had been picked up by the J.P. Knapp Foundation, some observers wondered if the owner and publisher of Architectural Digest, Cleon T. Knapp III, had used his family’s charitable arm to help obtain the Reagan White House exclusive. By the present-day standards of presidential corruption, such venality seems small potatoes, but in those more innocent times Rense’s part in the transaction appeared to be a quid pro quo.

Leafing through her unintentionally hilarious Architectural Digest retrospective, it is easy to discern a through-line from the lust for glittering opulence that characterized the Reagan White House to the still more repellent style embodied by Trump Tower, Mar-a-Lago, and assorted golf clubs owned by the incumbent president. The Rense-inspired drooling over celebrity, money, and power that have accompanied both is depressing, as well as symptomatic of social values with far worse implications for the nation.

Architectural Digest: Autobiography of a Magazine 1920–2010, by Paige Rense, is published by Rizzoli.