What sounds like a mechanical air-raid siren morphs into a human cry of loss at the start of The Head & the Load, a powerful ninety-minute stage production about the role and remembrance of Africans in the first truly global war. Conceived and directed by the South African artist William Kentridge, the work was created for the World War I centenary that culminated with Armistice Day on November 11, and will be staged in New York in December. It is part of a wave of work by artists and historians that has challenged World War I’s monochrome image. Kentridge’s piece and other ambitious centennial art works and exhibitions raise profound questions about the selectiveness of remembrance and how those who have been willfully erased can best be restored to memory.

The Head & the Load was co-commissioned for 14–18 NOW, a UK arts program to mark the centenary whose imaginative projects have ranged from a stunning staging at London’s Barbican Theatre of Alice Oswald’s Memorial (2011), an elegiac poem for the hundreds of dead soldiers named in Homer’s Iliad, to a fireboat in the New York Harbor painted by Tauba Auerbach to recall the “dazzle”-camouflaged ships of World War I naval battles. “Lest We Forget?” at the Imperial War Museum North in Manchester, curated by Laura Clouting, traces both intimate and official ways in which the war dead and disabled of Britain and its Empire have been mourned and memorialized. The objects on display range from dried poppy petals enclosed in letters from France to a Ouija board for the séances that became popular as casualties soared. Along with a scrawled manuscript of Wilfred Owen’s poem “Dulce et Decorum Est” are official war paintings for a Hall of Remembrance that was never built. An unstated reason for that neglect may be surmised from works such as Gassed, John Singer Sargent’s Renaissance-scale oil painting of a piteous line of soldiers blinded by mustard gas. In terms of the official response to the terrible losses, the uniformity of Western Front graves is described in the exhibition as “an unprecedented democracy in death.” Yet not everyone was enfranchised, and not all theaters of war were equal.

An opening section on “Dealing with the Dead,” with a wall of slides of strewn corpses and battlefield graves, traces how an official “commemorative legacy” grew in response to unprecedented carnage caused by pulverizing weapons. By 1919, “some 559,000 British and Empire casualties had no known graves.” When a controversial wartime decision not to repatriate the dead was affirmed, the question of how to honor these men at the fronts—so many of whom were volunteers—led to cemeteries of standardized gravestones, to be tended by the Imperial (later Commonwealth) War Graves Commission in perpetuity, and monuments inscribed with the names of the missing. Sir Frederic Kenyon’s 1918 report, War Graves: How the Cemeteries Abroad Will be Designed, laid down the universal principles. “No difference could be made between the graves of officers or men,” wrote Rudyard Kipling, the commission’s literary adviser.

Partly because religion had been a catalyst of the Indian Uprising of 1857, equality of race and creed was also affirmed by the commission. Makeshift wooden crosses were replaced with rounded white gravestones (a secular move vehemently opposed by Lady Florence Cecil and 8,000 co-petitioners). The architect Sir Edwin Lutyens designed London’s austere Cenotaph in 1919, arguing that, for a symbolic empty tomb for the “faithful” across the Empire, “It would be an unchristian act to offend men of different faiths.” On display in Manchester are Herbert Baker’s designs with stone tigers for the 1927 Neuve-Chapelle Memorial in France that named the 4,742 Indian soldiers and laborers missing at the Western Front.

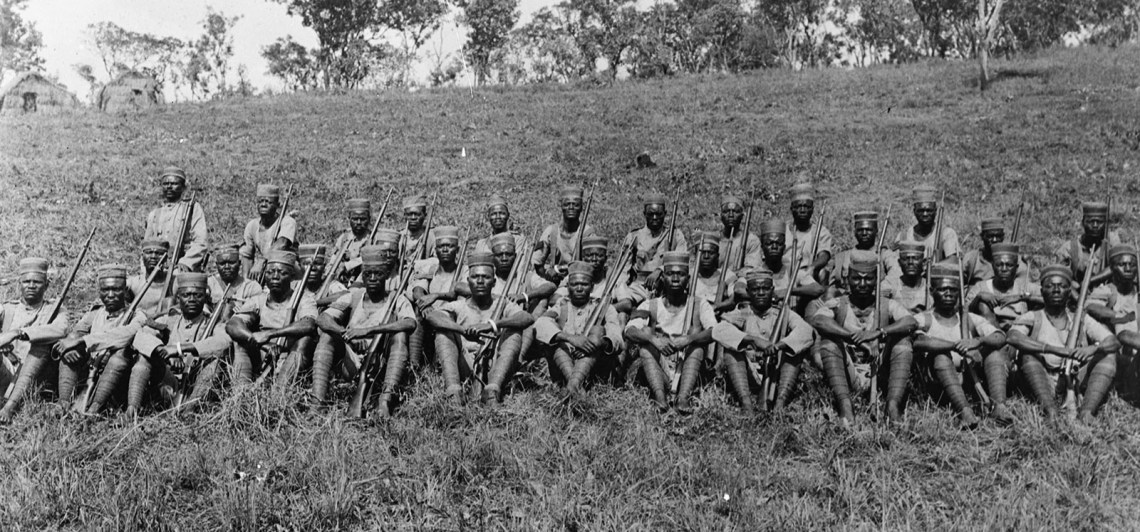

A coda to “Lest We Forget?” labeled “The Empire Remembered?” hints at how far reality could diverge from the stated aim of “identical treatment of British and native troops,” as “circumstances permit.” In East and West Africa, for example, where 8,000 black soldiers, including West Indians, were killed fighting for Britain under white officers, the names of an estimated 120,000 African laborers and porters of the so-called Carrier Corps who died, mainly from sickness, “were not inscribed onto formal memorials. A complete record of their identities does not exist.”

Some historians have gone further in impugning a “systematic inequality” in official remembrance. According to Michèle Barrett, writing in Santanu Das’s exemplary collection, Race, Empire and First World War Writing (2011), many Africans’ graves were deliberately abandoned. Some names were reallocated to memorials and officially “sent missing,” as though those men had no known graves—which was a lie. Their families were never to know where they were buried. Barrett, who contends that “the argument about inadequate records often functions as a screen,” also found evidence that a common grave at Salaita Hill in East Africa had been sifted and sorted to determine the racial identities of the skeletal remains (including by skull shape), which would then determine the care with which they were memorialized.

Advertisement

Monuments in Mombasa, Nairobi, and Dar es Salaam, inscribed to “Arab and Native African troops” and the “Carriers and Porters who were the feet and hands of the army,” display no names or even numbers of dead. Instead, they bear Kipling’s vacuous consolation: “If you fight for your country, even if you die, your sons will remember your name.” Official reasons for not respecting colonial war graves included “waste of public money,” and that Africans had not reached a “stage of civilization” to appreciate them. Yet the colonial authorities were also fearful that such vast reminders of the scale of sacrifice made by British subjects would lead to unrest. According to Barrett, the British governor of Tanganyika urged that the “vast Carrier Corps cemeteries in Dar es Salaam and elsewhere should be allowed to revert to nature as speedily as possible.”

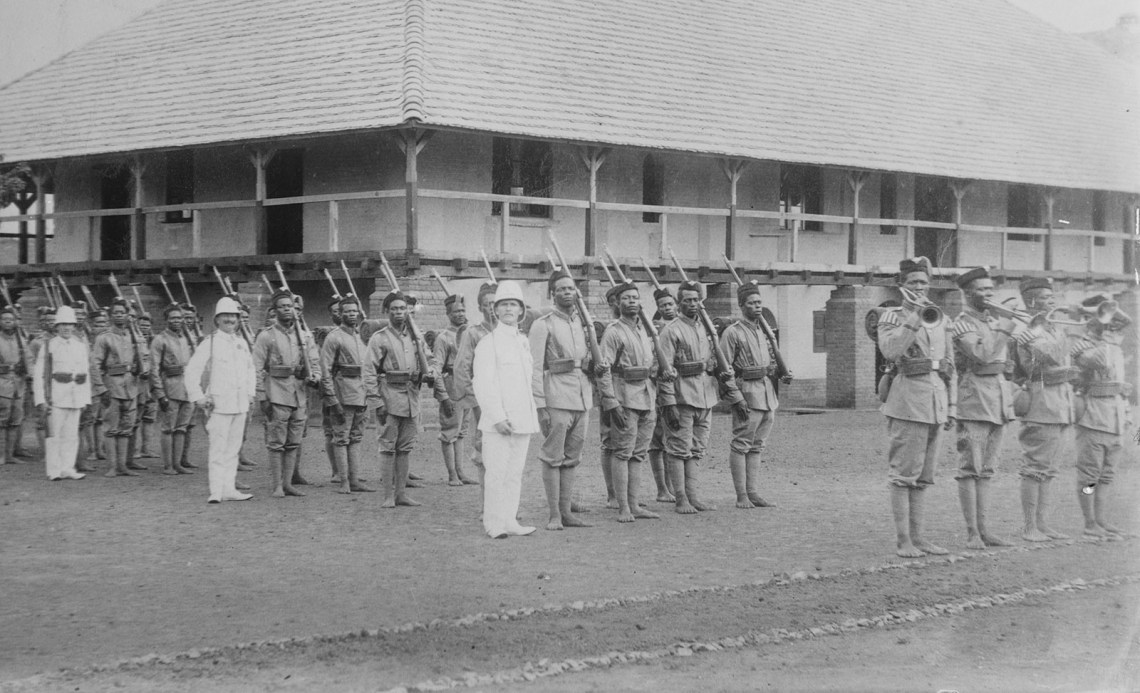

In wartime, the service of Africans and Asians was widely reported. Yet, as the abandoned war graves suggest, enforced forgetting can be a more brutal business than the tweaking of text books, the mere “airbrushing” of history—particularly when that service and sacrifice had stoked expectations around the globe. As the British-Nigerian historian David Olusoga said in a talk at Tate Modern before The Head & the Load, “Indians, North Africans, French West Africans on parade was one of the great stories of the war that journalists couldn’t get enough of, because it was romantic and exotic. Then that stops almost immediately the great guns fall silent. Decade by decade, the war becomes monochrome while the bones are still leached in the jungles.”

Over the past two decades, this illusion has been assailed by a growing body of scholarship, as well as oral history and archival finds (by historians including Das and Olusoga, on whom I have drawn). The World’s War: Forgotten Soldiers of Empire (a 2014 book tied to a BBC TV series) is Olusoga’s powerful account of how the European nations fought on global fronts for imperial spoils, using colonial manpower—both voluntary and press-ganged. The industrial killing required a vast mobile labor force to move supplies, dig trenches and bury the dead. Over the course of the war, for example, nearly 1.5 million volunteers from pre-partition India served in the British army, while some 3,000 Africans a month were forced into its Carrier Corps. In French West Africa, sons were demanded as a “blood tax” for the benefits of French civilization. German forces in East Africa, later in the war, openly abducted men from their villages. Though many volunteers joined up to keep hunger at bay, independence leaders from Mahatma Gandhi to Marcus Garvey argued that loyal service would reap rewards in self-rule—a dream harshly dispelled.

In wartime, the racial hierarchies of the day had largely determined who could bear arms or command, who could eat with or nurse whom. Men of color fighting against white men in Europe, and alongside them, risked undermining the racial mystique that underpinned colonial rule. That this fear was well founded was later evident. The late Senegalese novelist and filmmaker Ousmane Sembène, drafted into the Free French Army in 1944, discovered with his generation the irony of helping Nazi-occupied France fight for a liberation denied his own people. He also told me during an interview in 2005: “In the army we saw those who considered themselves our masters naked, in tears, some cowardly or ignorant. When a white soldier asked me to write a letter for him, it was a revelation—I thought all Europeans knew how to write. The war demystified the coloniser; the veil fell.”

Fear of this demystification often overruled military imperatives. Indian sepoys initially had a decisive influence on the Western Front. But those infantrymen who had docked in Marseilles to shouts of “Vivent les Hindous!” were swiftly redeployed to Mesopotamia. Britain’s African troops were barred from European fronts. France, which recruited 500,000 troops from Africa and Indochina, used Tirailleurs Sénégalais on the Western Front, but as cannon fodder. Germany, whose propaganda claimed that deployment of African and Asian troops in Europe was a war crime and race treason, recruited 14,000 Askaris (mercenaries) for East Africa, where they would fight other Africans. Some 75 percent of the British West Indies Regiment and 80 percent of African-Americans were confined to labor units. Discrimination in pay and rations while under indiscriminate shell fire partly explains why these men sought the status of soldiers not auxiliaries—usually to no avail.

Advertisement

African-Americans, under French command, “fought a double battle in France,” wrote Jessie Redmon Fauset in 1924, “one with Germany, and one with white America.” French respect, in particular, alarmed US authorities. A secret memo from the American Expeditionary Force headquarters in August 1918 urged French officers and civil authorities not to treat African-American officers as equals (by eating with them or shaking their hands), nor to commend the troops too highly or allow “familiarity” with French women (Mississippi Senator James K. Vardaman expressed loathing, in a choice phrase, for “French-women-ruined Negro soldiers”). Any such indulgence, the memo argued, would upset both white Americans, as “an affront to their national policy,” and “experienced” French colonials, “who see in it an overweening menace to the prestige of the white race.” The intimacy entailed by nursing was also frowned upon as “lowering the prestige of the white woman.”

Some of the thousands of wounded Indians evacuated to England were photographed, for recruitment purposes, convalescing under the faux-Mughal domes of Brighton’s Pavilion hospital. Yet the Army Council sought to bar women from nursing them. Patients were fenced in, and allowed out only under male escort.

Official betrayal was epitomized in Britain by the Victory Parade of July 19, 1919. Lutyens, whose Cenotaph in London was the saluting point, may have sought to embrace all the Empire faithful, but Colonial Office officials deemed it “impolitic to bring coloured detachments to participate in the peace processions.” Indians were among the 15,000 soldiers, sailors, and airmen on parade, but West Indians and Nigerians were not. Nor were there African-Americans in the US contingent in Paris. Officially, these men’s wartime service was to be buried as deliberately as the carriers’ graves under weeds.

Amid institutionalized forgetting, art shakes us awake. The world première of The Head & the Load, which I saw at London’s Tate Modern last summer, was met with a standing ovation, five-star reviews, and murmurings of shock at an “unknown,” “untold,” or “forgotten” scandal. In line with Kentridge’s past in Brechtian theater during apartheid, the work is part memorial, part provocation. On a fifty-five-meter-wide runway of a stage in the gallery’s cavernous Turbine Hall, it had moments of terrible beauty. The music of composers Philip Miller and Thuthuka Sibisi, and choreography of Gregory Maqoma, provide an electrifying current of African resistance, inciting questions not only about colonial plunder and wartime exploitation, but also about the process by which these facts were obscured—and their recovery by art.

“It’s about what we’ve chosen not to remember,” the Johannesburg-based artist told me at the flat near the British Museum where he was staying for the week-long London run. The son of anti-apartheid lawyers, Kentridge read African studies at the University of Witwatersrand, but knew almost nothing of World War I in Africa: “Frustration at my own ignorance was part of the goad.” With influences from Goya, Hogarth, George Grosz, and Max Beckmann to Dumile Feni, Kentridge became internationally known in the 1980s for animation shorts made by filming his charcoal drawings, erasing, redrawing, and re-filming them. This “stone-age” technology leaves stubborn traces that highlight the erasures. According to a persuasive new monograph, William Kentridge: Process as Metaphor & Other Doubtful Enterprises (2018) by Leora Maltz-Leca, this technique was developed in response to apartheid censorship, at a time when the black marks of redaction in newspapers were being banned as subversive. The regime’s ultimate goal was to prevent awareness that anything had been withheld.

The scandal at the heart of Kentridge’s new production concerns the porters recruited from across the continent to serve British, French, and German forces in Africa. The Carrier Corps absorbed most of the 2 million Africans mobilized in the war, of whom at least 200,000 died. The real toll is unknowable; no army kept complete records. As many as 1 million Africans may have perished as marching armies requisitioned food and field hands, spreading famine and disease (with 200,000 deaths from Spanish flu alone). The wartime brutality followed the atrocities of colonial campaigns such as the Maji Maji war of 1905–1907 in East Africa and the German genocide against the Nama and Herero in Southwest Africa (today’s Namibia) in 1904–1908—the subject of Kentridge’s 2005 installation Black Box. Testing grounds for the machine-gun, these forays foreshadowed the mechanized slaughter about to come home to Europe.

The first British shot of the entire war was fired by a West African soldier in Togoland, a German imperial protectorate encompassing what is now Togo and part of Ghana. Togo, Cameroon, and Namibia soon fell to the Allies. But their invasion of Tanganyika led to terrible loss of life in protracted fighting; the German General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, a veteran of the colonial genocide in Namibia, even fought on, oblivious, for two weeks after the Armistice.

On the Western Front, horses and mules carried supplies. In Africa, where the tsetse fly and mosquito killed off the oxen, loads were borne on men’s backs. “For every soldier, three carriers. For every officer, nine carriers. For every machine-gun, twelve carriers. For every cannon, three hundred carriers,” intones a master of ceremonies in mustard-colored jacket, played by the actor Mncedisi Shabangu, relaying the British military’s “advanced arithmetic” in English and Xhosa. “For every man who dies from bullets, thirty-one die from disease.” Yet, he goes on,“they are not men because they have no name, or soldiers because they have no number.” Their deaths were recorded, if at all, as “wastage.”

The production’s title is taken from a Ghanaian proverb—“The head and the load are the troubles of the neck”—which may allude to both physical burdens and colonized minds. For Kentridge, “people carrying the world on their shoulders, moving across the world with loads, is the dominant image of the war.” It is also his signature motif of the past three decades: from live actors to puppet projections, processions have been his versatile metaphor for everything from history and regime change to failed utopias. The carriers’ procession harks back to enslaved forebears (“Ropes were put through their ears as they were tied together”), and toward descendant miners and industrial workers.

The new project represents history through absurdist collage. Along with projections of Kentridge’s drawings of African waterfalls are telegraph text, film clips, and ledgers. The libretto is composed of mutually unintelligible fragments: Dadaist poems translated into isiZulu, lines from Wilfred Owen into French accompanied by dog-barks. There are instructions from Kiswahili for Beginners, and Setswana proverbs from a 1920 collection by the black South African writer Sol Plaatje: “God’s opinion is unknown” and “Hunger makes no man wise.” Fanon, too, is quoted: “When the whites feel they have become too mechanized, they turn to men of color and ask for a little human sustenance.” As is a version of Conrad: “Annihilate all the brutes.” Amid the sonic terror of war rendered by singers (“kaboom,” “ta ta ta”), Tristan Tzara’s mocking words ring out: “This is a fair idea of progress.”

An eagle-helmeted Kaiser sputtering German-accented gibberish is trolleyed across the stage; his French equivalent declaims from a watchtower—the burlesque cabaret recalls what Dada’s founders recognized in 1916, that war had robbed words of meaning, just as the Surrealists mimicked shell-shock. But the bricolage, which includes projected footage of enormous scissors devouring maps, is also a response to lacunae in colonial history and the carve-up of a continent: Versailles, where Germany’s African territories were divided as spoils among the victorious Allies, sealed the Scramble for Africa. Rare ethnographic recordings made in prisoner-of-war camps near Berlin were also a starting point for Kentridge’s composers, whose own collage of musical quotations ranges from Satie and Schoenberg to a Mandinka melody.

“Constructive amnesia” is Kentridge’s term for the process by which the porters were actively forgotten. The Head & the Load, Kentridge told me, was “to note my own ignorance and that of others. Here are things that are gone that should be remembered.” Why they are gone is hinted at in a quotation from a wartime military official: “Lest their actions merit recognition, their deeds must not be recorded.”

Another 14–18 NOW commission, Mimesis: African Soldier, a video installation at the Imperial War Museum in London by the British artist and filmmaker John Akomfrah, gives poetic expression to the sense of rewards due yet withheld. The seventy-five-minute, three-channel video installation draws on obscure film footage, including archival material from Senegal, Ghana, and Kenya, to build an astonishing composite of soldiers and laborers from Africa, Asia, and the Americas being signed up, feeding supply lines, and converging on fronts, from Flanders mud to jungle, desert, and veld.

Akomfrah, who had his first US retrospective recently at the New Museum in New York, splices the black-and-white documentary footage with staged tableaux of seven actors in distinctly colored colonial uniforms, wearing fezzes, kepis, or turbans. We see them solitary on ship decks, or wrenched from women in silent, depopulated villages, or wandering on overgrown battlefields where flags mark the fallen of many nationalities. A soundtrack with songs and whizzbangs hisses to simulate the terrifying release of mustard gas as yellowish smoke fills the screen. The artful placement of props, from displaced furniture and ownerless kit bags to archive photographs under flowing water, creates a powerful sense of rupture and desolation. Subtitled The Ambiguities of Colonial Disenchantment and signposted with titles such as “rude awakening,” and “letdown,” the new footage with actors becomes a little formulaic only toward the end.

The final, ironic footage is of colonial commanders embracing troops and pinning medals in a hollow masquerade of recognition. The film’s epigraph from Rosa Luxemburg, “Those who do not move do not notice their chains,” fits the mass mobilization of both the colonized and the carriers. Both Akomfrah’s new work and Kentridge’s reminded me of something the late Nobel laureate Günter Grass, whose novel The Tin Drum (1959) countered German amnesia after World War II, said to me when I interviewed him in 2010 at his home in Lübeck: “Perhaps in time your country, England, will think about its colonial crimes… Everybody has to empty their own latrine.”

“We have obligations to the dead,” Akomfrah writes in a note on Mimesis, quoting the historian Carlo Ginzburg. Yet memorials are for the living, too.

At London’s busy Hyde Park Corner, four urn-topped pillars flanking the road to Buckingham Palace commemorate the “service and sacrifices of five million men and women from the Indian Sub-continent, Africa and the Caribbean, who volunteered to fight with the British in the two World Wars.” The Memorial Gates on Constitution Hill—erected in 2002 after decades of lobbying—are inscribed as a “debt of honour.” Another memorial was unveiled last year in Windrush Square in Brixton, South London, to commemorate African and Caribbean war service. Recently announced is one for London’s Docklands to honor the 140,000 Chinese laborers who served the Allies on the Western Front. Their duties included clearing shells and reinterring the remains from mass graves.

In the pointed inscription on the 2002 monument: “With so many descendants of these volunteers now living in the United Kingdom, the Memorial Gates serve to remind us all of our shared sacrifices in times of greatest need.” War service has become a certificate of still-contested belonging. Gaps in official versions of the past can undermine people’s claim to the future. During the Windrush scandal this year, those demanding residency rights for the generation of Caribbean migrants who settled in Britain, as British citizens, in the 1940s and 1950s invoked the West Indian contribution to both world wars. As the “Lest We Forget?” exhibition traces, the Black Poppy Campaign to recognize African and Caribbean war service began in 2010, partly to counter the far right’s co-opting of the red poppy as a nationalist symbol.

Yet curious blind spots persist. Up the Thames from Tate Modern, “Aftermath: Art in the Wake of World War One” at Tate Britain ostensibly explored the artistic legacy of the war in Britain, France, and Germany, and “how memories of the war were filtered through… political agendas.” Yet this otherwise thoughtful exhibition placed Europe’s overseas territories outside its scope. It traced the manipulation of war memories through the visibility of disabled veterans at official parades (France made much of mutilés de guerre; Britain hid them), but made no mention of black soldiers whose invisibility was as politically driven.

Other than a reference to memorial sculptures depicting “white bodies,” there seemed little recognition of Britain and France as imperial powers whose empires were enlarged by Germany’s defeat—a silence filled with unspoken ironies. Votes for women in Britain and Germany were held up as a reward for war service without reference to the millions—women and men alike—whose hopes of emancipation were crushed. No insight was offered into what a nostalgic “return to order” might mean for much of the globe, or a French rediscovery of classicism aligned with “national identity” and “values of civilization.”

In 1918, the British War Memorials Committee was part of the Ministry of Information, the government’s propaganda arm. After the war, William Orpen’s oil painting To the Unknown British Soldier in France (1921–1928) was barred from the official collection until the artist removed the skeletal spirits of naked, dead soldiers and hovering cherubs he had painted beside the flag-draped coffin at Versailles. The catalogue for “Aftermath” shows both the altered painting and a photograph of the original with its ghostly apparitions. The absence of black servicemen from the Victory Parade was as much a propaganda exercise as censoring war art—with one eye to colonial control, the other to projecting a desired image of the nation into the future.

“Aftermath” noted that there were “few official memorials to the servicemen from Asia, Africa and the Caribbean.” But at a preview I attended, the Cenotaph in Frank Owen Salisbury’s oil painting The Passing of the Unknown Warrior, 11 November 1920 (1920) was described as representing all British and Empire dead. This essay was triggered by that half-truth: Could it be that, in an age of high imperialism, there was genuine equality in war remembrance? Or was the idea that Britain and Empire fought shoulder to shoulder, as brothers-in-arms, to face a democracy in death, a projection back from our own time—itself a kind of airbrushing of history?

British war graves policy is now, where possible, to “correct anomalies.” Yet, if the past is another country, how they did things differently—at times, pathologically—should be spotlit, not smoothed away. We need to be aware of the skeletons beside the coffin. Like Kentridge’s charcoal traces, we can at least remember what was erased, or made so painfully and violently to disappear from memory.

The Head & the Load will be at the Park Avenue Armory in New York from December 4 through 15. Mimesis: African Soldier is at the Imperial War Museum, London, until March 31, 2019; and “Lest We Forget?” is at the Imperial War Museum North in Manchester, England, until February 24, 2019.