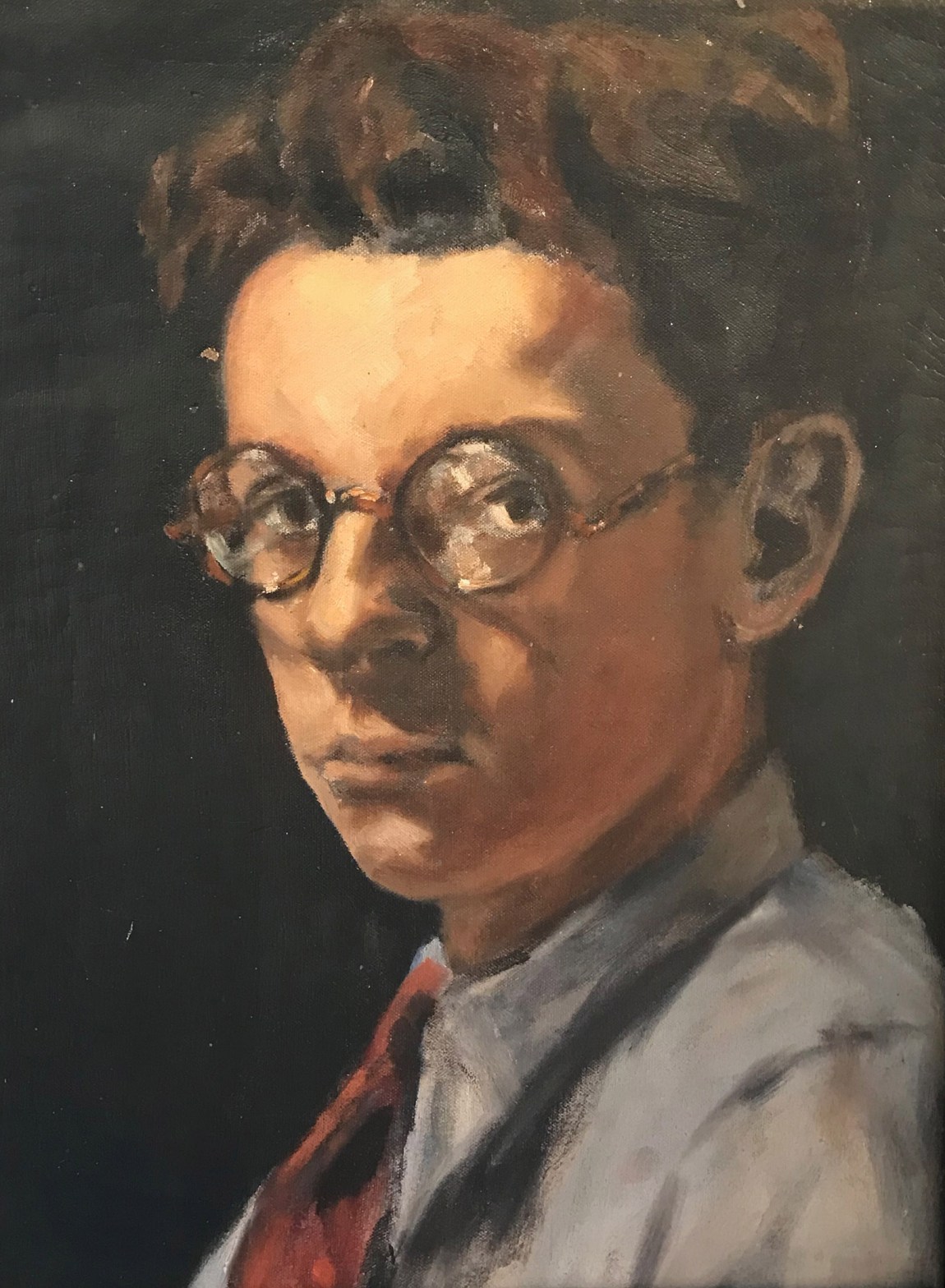

I never could figure out how I felt about my father’s work. Protective, proud that he was an artist. But did I like the pictures? With some, there was and is no problem: the early portraits. Most of these are pencil drawings, and there is no question but that, from the youngest age, he was uncommonly gifted. They look like the naturalistic renderings of nineteenth-century masters, only, somehow, modern. Few survive—two of his mother, with her square, homely face and glasses, and one of his younger brother Joe, when no one knew he would soon die, at twenty; and a magnificent self-portrait in oils, done at sixteen. It was always my favorite of his paintings.

After that, nothing naturalistic, and no drawings from life from him—not until David was in his late eighties. At sixteen, he assumed the art was over. In the next few years, his second-oldest brother, Louis, developed a cough and night sweats. Go to the doctor, Lou! They all said it; they knew what it was. But Lou wouldn’t go; that was why Lou wouldn’t, as if he could stave it off by not hearing the word pronounced: tuberculosis. The six brothers had a single bedroom, three double beds; my father shared with Lou (it was sometime during this period that they were reduced to five young men by Joe’s death). When Lou’s diagnosis could no longer be denied, he and Dave went off to a sanitarium run by a Jewish charity, in the New Jersey countryside. It was 1936; my father was twenty.

He expected to die, but the exile was the making of him. David took courses in studio art at the “san,” as he always called it. He was also educated there, less formally, in leftist politics, and that affected the art, too. The style is named Social Realism, but it was rarely realistic in this country. It was figurative but highly stylized and all message, symbolic. Whereas those early works of my father’s were intensely about the individuals, about particularities of light and observation, Social Realism elicited images of the generic: every man was an everyman. David Shapiro could have had the career of the successful Raphael Soyer, or possibly of Alice Neel, who didn’t enjoy success until her seventies (though enjoy it she did). Instead, he was dismissive of that kind of work, sneering even—“life class.” He looked up to Orozco, Diego Rivera, leftist New World muralists. Qua career, the one he aspired to might have been Ben Shahn’s, whose work was popular, and poetic as well as political: even Shahn’s prints of Sacco and Vanzetti (railroaded immigrant anarchists) were more soulful than angry, simple, stylized drawings that became emblematic posters for left-liberal causes. Sometimes my father’s work was bracketed with Shahn’s, the more familiar and famous image-maker. This could seem demeaning, like being an also-ran, or validating.

My father felt so much more ambivalence in all of this than the sneering or admiration might imply. Unpredictably, he’d reverse himself and express a contrary opinion, sometimes in the space of one sentence. I yearned for his work to succeed—for him to have what he needed—and I sometimes thought I could see why it wasn’t being snapped up. Though my heart might bleed for the causes Social Realism represented, in the 1960s, when I came of age, the style was embarrassing. It was unironic. It was square. His pain, as he failed to achieve the career he’d been led to expect by early successes, became mine.

After the san, he had gone to the American Artists School, on 14th Street, founded by members of the John Reed Club, one of those infamous “Communist fronts.” That was in its favor. By no coincidence, it was free—a people’s art school. After art school, he won prizes. He’d won prizes for his art in high school, and even earlier. Just as the US entered the war, he was awarded a national prize for a poster: CIO Organizes Oil for Victory.

Teaching first at Smith College, he then accepted a post at the University of British Columbia, followed by a Fulbright fellowship to Rome. It wasn’t long after the war, 1951, and he fell in with a group of leftist Italian artists camping out in what had been the German Academy in Rome, the Villa Massimo. He and the Villa Massimo artists debated socialism, communism, and art. One of the most prominent among the group was Renato Guttuso, known later to English speakers mostly through illustrations of an Elizabeth David cookbook, but with paintings exhibited widely in Europe.

Advertisement

David’s path in Rome also crossed that of the American Robert Gwathmey, whose color-block-style portraits of beaten-down black people sold sturdily; Bob’s wife, Rosalie, showed with the Photo League, another banner outpost of American communism. David worked out imagery in Rome that would typify his paintings and prints for many years, of Italian hilltowns and resigned women in nunlike headdress carrying sticks of bread.

Back in New York in 1954, he was not a famous artist, not a visiting Fulbright fellow, not a resident of the Villa Massimo but another striving son of immigrants, another Russian-Jewish Brooklyn boy, and a father, with two young children to support. Maybe he was perceived as less up-and-coming, or he’d just been away at a crucial time. The art world was undergoing a transformation, a change in orientation. From the time of the Ashcan painters, if not earlier, the drive had been to make American art, not work derived from Europe. In absolute terms, this was impossible, unless you were Native American and probably not thinking of your totem poles or beadwork as art, but it was a widespread impulse, as responsible for Aaron Copland and Martha Graham as for Thomas Hart Benton or Grant Wood.

From 1948, however, Abstract Expressionism was being presented as the avatar of American freedom and individualism, written about, shown, and supported as no American art ever had been. David had come back to the age of the anticommunist McCarthy campaigns hand in hand with Modernism. It felt like a conspiracy against art of his kind. (As he was to discover, this turned out to be true. My mother had begun to write in the 1970s, and together, they published a groundbreaking essay documenting the links between the CIA and the promotion of Abstract Expressionism. Boosted as propaganda for American freedom, Abstract Expressionism had engulfed the center of the art world, New York, with international opinion to follow.)

Quality of work is not necessarily measured by degree of worldly recognition; the two can be grossly out of whack—in either direction. But it is very hard for artists to believe this, to feel it. My father’s career and his standing, as distinct from his aesthetic achievements, was hugely important to him. His dignity was wounded, even though having work shown in New York’s unforgiving art scene was itself an achievement. He had a one-man show at a 67th Street gallery just off Fifth, with catalogue essays by writers whose names could cause excitement in the art world. His work was bought by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Smithsonian, and shown in galleries around Europe. By the Seventies, in his teaching career, he’d earned the title of professor, with tenure, teaching studio art and art history, on the basis of his standing as an artist (his art-school certificate was not a college degree).

Moderate success felt like failure to him. This is a phenomenon well known in the arts, fields so brutally competitive, subjective, and judgmental. But could he have been more successful if he’d followed up more closely on the works of his that were most aesthetically satisfying to, for instance, me? When my sister and I were dividing his work after our parents’ deaths, it didn’t seem as if the division would be hard: she preferred the later works, I the earlier. It proved not so simple, in that way: whatever the period or genre, there were certain works that were just better, or best. Certain themes, individual examples of which could be excellent, became oppressive in their repetitiveness, but that’s normal: as an artist, you have your donnée.

As we investigated the racks in the barn he used as a studio, pulling out long-unseen work dating back to before our births, we discovered a gorgeous early city scene, mostly black, of apartment windows lit at night in different yellows and whites. There, he found a perfect match of subject to style. It conveys or engenders pathos, a sense of seeing something unaware of being seen, and there’s a wit or humor to the rhythm of lighted and dark windows—not to mention authenticity and familiarity: he had looked at such scenes all his life, long before he looked with any kind of calculation about what images to make.

His best works almost invariably had what that cityscape had: the fusion or coincidence of the decorative element with an exact correspondence to reality, a place where the schematic becomes naturalistic and the literal takes off into metaphor. (Maybe, in that connection, it means something that his first scholarly book was about a nineteenth-century American painter named Washington Allston, who invented the term “objective correlative.”)

Advertisement

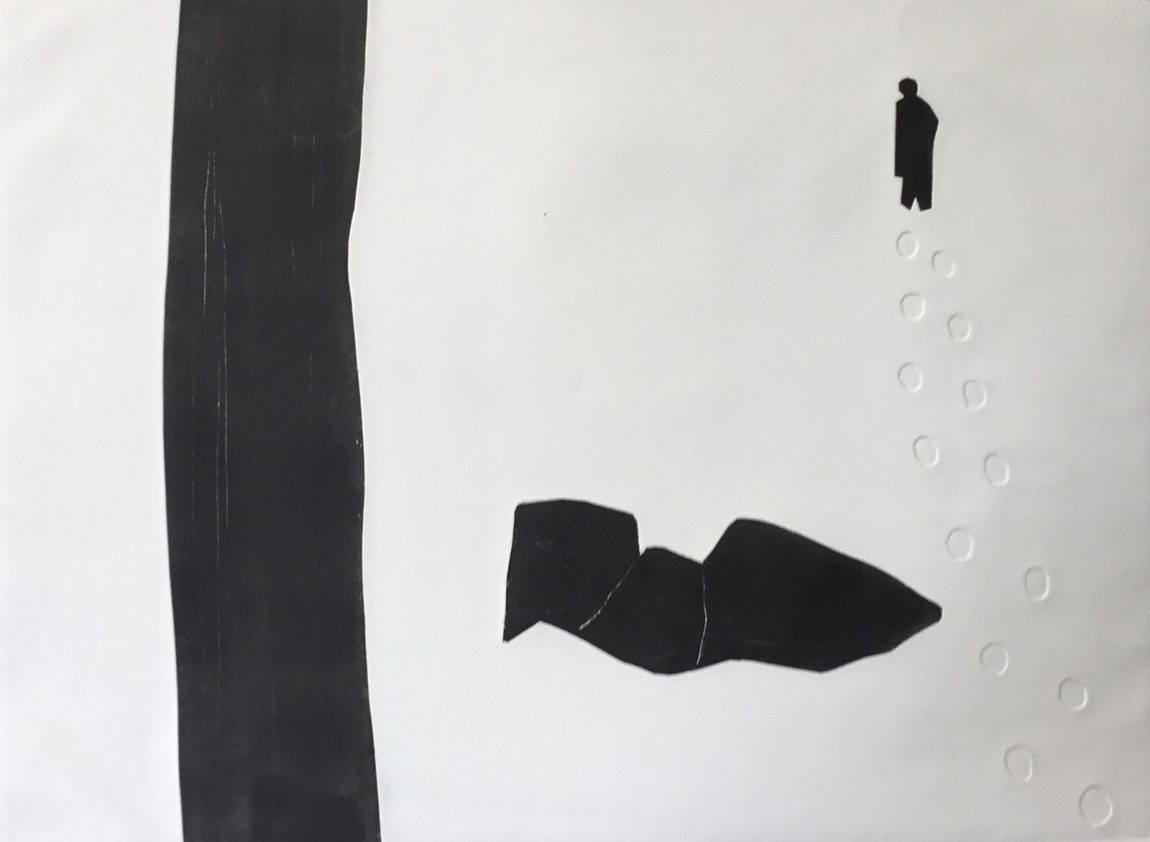

His bestselling print had this fusion, and it was unquestionably the reason for its popularity, a work called Winter Walk. It reflected the oneness he felt with the land in Vermont, where he began spending time in the Sixties and where he and my mother moved in 1979. It was marketed through the Associated American Artists gallery on Fifth Avenue, which sold prints that middle-class people could afford, and by far outsold any of his other graphic art, whether offered through AAA or other galleries.

In it, footprints are pressed indentations in the thick paper, white-on-white intaglio, just as real footprints indent real snow; the trees are black, the human figure is a silhouette; in later variations—he did further editions, with a stream or rocks, to meet demand—he kept to this scheme of white-on-white footprints and black figuration, all of which match the way such things appear in an actual snowscape. It has all the simplicity of abstraction and reduction but offers the pleasures of naturalism. The lone figure could declare alienation, as some of his Sixties paintings bathetically did, but it as easily suggests communion with nature.

Similarly, there’s a painting he did of bare trees, black against stippled greens and turquoises, where the rich, bright colors get darker as they move up the picture plane, exactly the way shadow in woods gathers with distance, giving an effect of deepness without explicitly showing it. There are several variations on this image, but only one painting has the ombré darkening and therefore the implied perspective, and it is wonderfully satisfying.

And then there were works both of us really hated, that could make my sister shriek. I think we both had a No, don’t do it feeling about these, a wish that we could protect him from himself. We could hardly bear anything that would justify a negative verdict. The worst examples suffered not because his style changed but because they followed a too controlling and underlined idea; or they made one squirm because the idea was too grand for the expression. There were the alienation ones and the woe-filled ones, both of which felt like hands being waved in your face.

Alienation as a posture and a pose was a trope by the mid-Sixties. Its oxymoronic clout filtered in by way of Existentialism and had its upshot in the pop-culture mandate of cool. Daddy was trying to be cool, which, by dint of its very effort, is uncool, daddy-o. It was certainly that case that, after the collapse of American communism in the Fifties, he was newly alienated. The trouble was, he illustrated this rather than let it merely manifest.

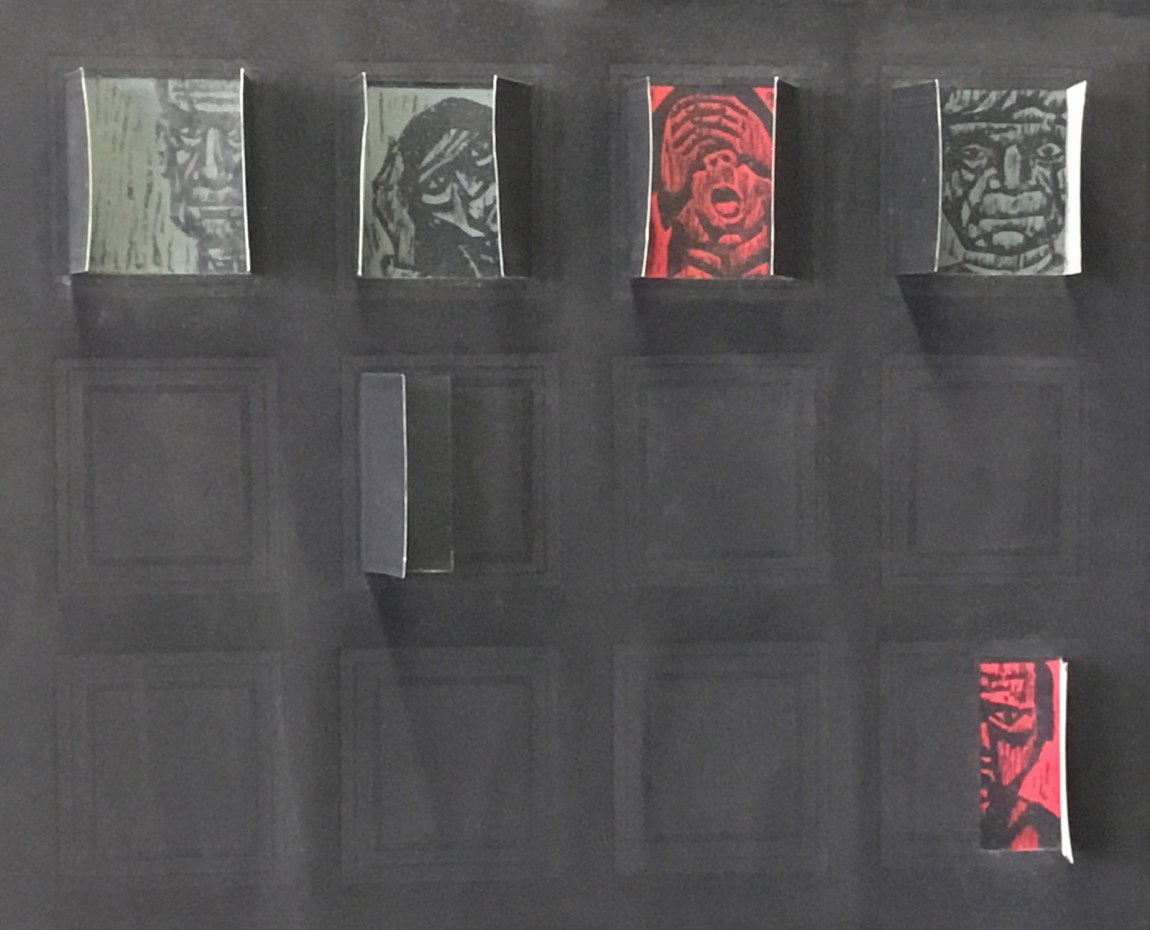

The nadir, I think my sister and I agree, were these woodcuts set behind a sheet of black paper with flaps like shutters—Advent calendars for the self-dramatizingly morbid. (Though I have to admit, they grow on me with repeated exposure.)

Cringe-inducing rather than laughable is a painting modestly titled Who Am I, which depicts Everyman as an artist standing next to his painting which is of an artist next to his painting which, etc.

A variation on it, however, that I am highly willing to entertain, shows the traditional artist in his studio, also titled Who Am I.

But it’s possible that what seems camp to a veteran of the Sixties will look charmingly of its time to a later generation, as my father’s early work does to me. I have more distance on it; it wasn’t created before my eyes (I have a hard time living with my own old drawings). Maybe my sister and I are reacting to the sheer Sixties-ishness of it all. The era is too close to us and too much part of us.

The alienation strain of that period strongly overlaps with the pictures that seem to ask you to feel sorry for the person depicted and, by implication, the painter who felt moved to render that person. (Or to admire the heroic figure, as with one called The Non-conformist.)

There are paintings of mourners and poor people by others that don’t have this effect, and I may only feel it because I am too close to the painter. He wasn’t a complainer or self-pitier—far from it—but his expressions of fellow feeling for me when he thought I was sad told me how deeply he wanted a companion in his melancholy. There is a sad balloon man, a sad rebbe carrying a Torah scroll (Sixties), an early painting of a pregnant woman keening over a coffin, and so on. The sad balloon man perhaps veers too close to a tearful clown. The sad balloon man, though done very straight, makes a nervous resonance with tearful clown or little match girl.

And there was the less ambitious—and maybe more relaxed—work, radically simplified and almost always pleasing, in posters and in handmade cards sent out at Christmas, made of colored paper cutouts, of a piece with the Valentines he gave to my mother each year. You can see the evolution of his style very clearly by the contrast of one from the 1940s, two years after their marriage, and one from the 1980s. (One year he missed: Valentine’s Day, 2005, the day he breathed his last.)

He also tried to make money illustrating children’s books. Only one saw the light of day—Hidden Animals, a kind of Where’s Waldo? of the natural world. Gouache paintings on illustration board for a story about a twin boy and girl’s first day at school, colorful and fully naturalistic, were hung (by me, because I related to them) above the wooden bed he built for my biggest doll. All this work was wantonly discarded when they moved to Vermont.

The Matisse-like cutouts, their patterns and joie de vivre, I did not appreciate as a child, but I do now. After my father died, I found in his studio a small woodcut proof in this style, brown silhouettes of a man and woman bouncing a baby in their linked arms, and a child with arms upraised joining in the jubilation, with hand-lettering in pencil gone over with ink, announcing my birth. I don’t think it was ever printed or sent out—and I doubt either my mother or sister was so filled with joy at the event—but this template now hangs over my desk.

Artists are affected by their times, some fired up by what’s around them, others merely accommodating it to their own manner, and still others entrenched against the popular or new. Any of these may prove to be an adaptive stance, aesthetically or by way of getting noticed. After the early naturalism of the portraits, my father’s work became highly stylized, netted by black lines (not unlike Shahn’s or those of another contemporary better known than David was, Leonard Baskin), with color that was only sometimes mimetic but mostly indulged for its own sake.

Even as he railed at the hegemony of abstraction, however, David moved toward it. As he advanced through middle age, the black lines grew lighter and were often overpainted by color, and the colors grew lusher and were almost never naturalistic. Like Milton Avery, he abstracted from nature but was unwilling to his core to be a formalist—to make work solely about color, line, shape, medium.

He worked with the color families that had been present from his earliest paintings of city scenes—a couple kissing beyond the cone of light cast by a street lamp, a young man against a wall of peeling posters, pigeons flocking for handouts—but the palettes of related color became more dominant as the figurative elements were downplayed.

The hilltowns he began painting in Italy, for instance, had always been rendered in bright blends of related rather than natural colors, in mottled blocks as if mosaic squares made of stippled oil paint. The colors are almost purely pretty, in a way that asks nothing of a viewer except to enjoy, as he had enjoyed the original that inspired the image, uninflected by politics or human emotion as such, or even ideas.

Eventually, a bifurcation between black-and-white and color took place—between woodcuts and paintings. He did a triptych of giant black-and-white woodcuts depicting the assassinations of the Sixties—Kennedy, King, Kennedy—and large woodcuts of other public, politically modulated events, unashamedly work of social commentary. Meanwhile, his paintings were mainly landscapes—recognizable images of mountains, reflecting summers in Vermont, and of waterfalls, streams, rocks, and trees, sometimes as shapes indicated by color, occasionally with the black lines that remained prominent in his woodcuts. He liked to say he was through with the human figure, fed up with people.

For the vigorous years of his life, from his forties into his eighties, this was what the paintings were. The black lines kept diminishing, colors were lush and closely related but were not the colors of what was represented, and the images were figurative but simplified, abstractions in the root sense of subtraction, with incidental detail reduced to the simplest components. In his early work, color is applied smoothly, often flatly. By the time he was in Italy, he was using short-bristled brushes to stipple, resulting in a stucco-like texture and allowing a borderless blending and changing of color like shadows on water. He painted on shiny brown masonite until, in later years, he started working on white, with the black lines mere wisps, fewer angularities, more curves, everything looser. Among these were paintings my sister and I both coveted—some enormous triptychs of sky, mountains, and forest or field; the moon tangled in trees; a lavender and yellow series of sun after rain, extremely light and free.

Toward the very end, bits of life study came back, but through the accrued style and in the sweet colors—blue-greens, orange-yellows, yellow-white, purple-blue-green, shades of pale green and lavender—and also pencil or ink drawings of flowers. He’d done flowers twice in his prime, in vases: one the Vermont chicory I loved to pick, the other probably bougainvillea from our one summer in Mexico, very recognizably in his style—winning one-offs. The later images were of growing flowers, carefully drawn, in an almost affectless style, when he was debilitated by stroke and age. I see them as tributes to my mother’s gardens. More typically, he was also simplifying and schematizing the landscape near the apartment where they spent winters by then, smaller paintings on thick white paper, of ocean waves and desert rocks in southern California.

I used to beg him as a child to paint the way he had in that adolescent self-portrait. It baffled me that he wouldn’t. Now I understand many reasons he didn’t, yet it still baffles me. For all that he railed against abstraction, he appreciated Malevich, Albers, and others, and he had schooled me in their work; it was the hegemony of formalism that was threatening, the way no room was allowed for anything else, just as he came into his prime. Conceptualism was breaking this chokehold when I was a teenager and art student in 1970; by chance I got to know some of its instigators, and was excited by it. For my father, this was betrayal—conceptual art was barely visual and certainly didn’t involve paint. He was disappointed in me—until I pointed out that at least conceptualism legitimized content.

But it’s not as if these aesthetic choices take place in a vacuum, or are even choices. You are of your time, willy-nilly. My father urgently wished to combine his talents and predilections with his politics, and he had been surrounded by those who did so. In that way, his beautiful early portraits probably looked to him jejune, reminders of an unawakened self—too natural. I can imagine this. He was, in a way, in his developed style, having his cake and eating it too: enjoying the play of color, the textures of paint, the rhythms of pure composition while staying close to his heart, to what he cared about in life. That’s what I saw.

But he was entering his work for competitions and shows to the end, and furious when it came back, repeatedly rejected in favor of the work of less accomplished but younger artists. As with many if not most in the arts, he loved the doing; he needed to make the art. But it was his letter to the world: he wanted it to go out into the world, and it was being sent back unread.

He was a professional. What is more, he always had to be “the best,” and he expected to be best. As a youth, he not only won art prizes but also troubled himself to answer a mere seven out of ten questions on tests, since seventy was the passing grade. He and his brother Irving had both been told they had genius-level IQs. Irving spent his entire working life in sales at an anti-aircraft facility. My father did his war work in such a plant—signing the required loyalty oath that he “was not and had never been a member of the Communist Party” while going to cell meetings—and later earned money as a draftsman in the plant where Irving worked. David disdained to use a ruler, trusting the accuracy of his eye: he only measured his drawings afterward.

Perhaps only rare artists can look coldly at what they do, see what they do best, and just do that. But many just do what sells best. In a brief stint as an art reporter, I was startled when, interviewing a number of up-and-comers, I’d spot a work in their studios that, almost always, I liked better than what they were known for—something quirky, playful—and they would deprecate it and say they couldn’t let people know about these, as if they were a vice. In turn, a few of my old classmates began to have work that sold well, to be prominently shown and written about. One who’d been a gifted draftsman and inventive painter had gotten noticed using media in a way that didn’t manifest those skills at all. When I expressed regret at that, he made it clear that this was what was wanted, this was what the dealers and curators chose. Another had created a stir with a style she eventually outgrew but felt her dealers demanded she stick to. This was before people talked about creating “brands,” but that was what these artists had done, created brands, however inadvertently. If Picasso had felt this pressure, we would have seventy years of Picasso Cubism, or maybe just rose-period Picasso.

I wish my father had more of the worldly success he’d craved and expected. I can’t help but feel that if more of his work had been as good as the best of it, he would have, though I’ve seen over and over how what is rewarded is not necessarily the best. I can’t even say that what is rewarded is what sells: what sells is very much a product of how and where it’s offered. Talent is not crucial, neither is skill; sometimes artwork or an artist just has appeal, though this is useless to invoke as a critical criterion, and it is also evanescent—try reading, for example, the most highly touted novels of twenty or fifty years ago. What does matter is persistence, and confidence. But confidence is not a rock. My father had it and also didn’t. And I’ve seen mediocre artists in various media become quite good ones simply because their mediocre work was hailed as better than it was: almost miraculously, this gives them the assurance to do better.

And there’s luck. The luck of being, having, the right thing at the right time, right place. Not remotely a judgment on who you are or the quality of what you do. But everyone, almost everyone, feels the responses of the world as a judgment on their work. It would be almost sociopathic not to. Status affects your very biological condition.

Once, as a high school student visiting a classmate who lived in Springfield, Massachusetts, I wandered with her into the Springfield Museum. At the top of a broad, grand staircase, and intended to knock you between the eyes, was a big landscape—one of Daddy’s! It was like coming by accident upon an intimate friend in a foreign country. I knew the museum owned his work, but so did lots of museums; this was unexpected and made me laugh out loud. His big gallery opening a few years earlier, on the other hand, had been anticipated by all of us as if it were a make-or-break occasion. It wasn’t as though we didn’t know the paintings inside out and upside down, however magnificently hung in the high-ceilinged rooms. It was the people we focused on, and it was a jittery, brittle affair. My mother’s keening at that week’s art reviews in The New York Times—in which the show outrageously did not appear—made me want to hide.

I remember my mother’s telling me about a Henry James story—one I don’t know the title of—about the family of an artist who conspire in revering his genius but in the end (if I’m remembering correctly), it’s revealed that they secretly felt he was not that good. Clearly, she felt this had some recondite lesson for her—but she “believed in” my father’s work. She felt that in worldly things—contacting gallery owners, soliciting recommendations from the well-placed, making necessary phone calls—he got in his own way, angrily refusing to do any of it.

It is my experience that most people in the arts feel a kind of comfort in lacking worldly success. They fight for success, and suffer over it, but it is so much safer not to have it—safer from envy, judgment, exposure; from the dangers attendant on superseding parents or companions—that, either through the work itself or by way of fumbling their encounters with the world, they ensure success won’t happen. But this need for self-defeat doesn’t seem true of my father. I think he naïvely, to the end, possibly through arrogance, expected the work to be its own ambassador. It had once been enough.

To put one’s work out there and not have it hailed is to feel as if one should never show one’s face again. The shame is incalculable. Attention must be paid.

In my early twenties, I couldn’t imagine wanting to hang my father’s work in my apartment. My sister did, and I marveled at it. I was at the age when you want to get away. You need to find out who you are, separate from your family. When I thought of putting his pictures on my walls, it was as if the weight of a frame dug into the back of my neck.

Now I have as many favorites of my father’s paintings on my walls as will fit. At my sister’s place, I delight in seeing such a plethora of his work looking just right in her large, white, airy rooms; I really hadn’t appreciated these big, more abstract works in our old, smaller spaces. But it is also true that I can’t see his work—any more than I could really see his face. There was never a time I didn’t know these images, and know them as an aspect of him. As it is, even coming across a piece of paper with his handwriting sends pangs through me, a wrenching longing to see him again, to talk to him. I never could figure out how I felt about my father’s work.