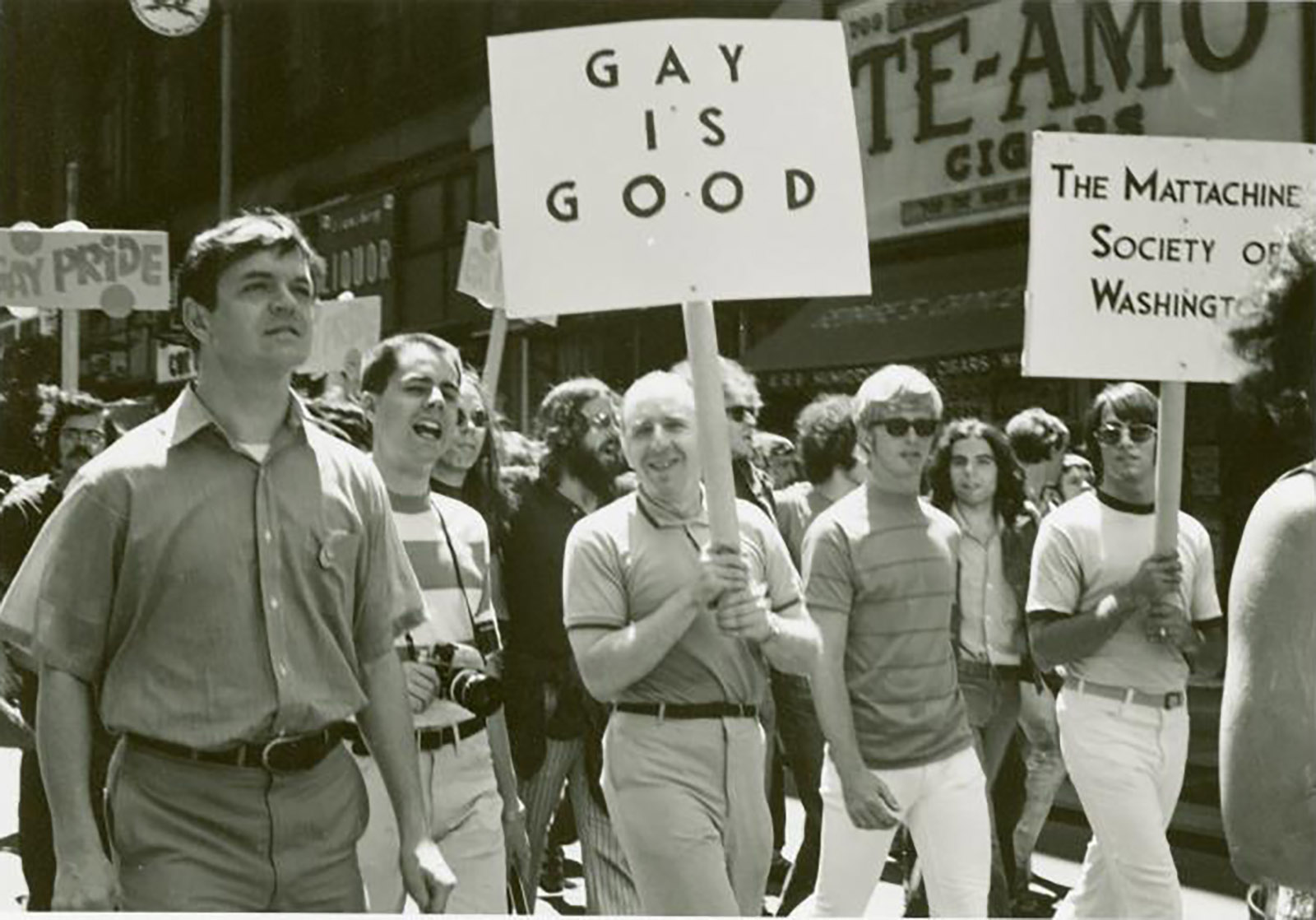

Kay Tobin/New York Public Library

Frank Kameny (center) with Mattachine Society of Washington members marching in the first Christopher Street Liberation Day Parade, New York City, 1970

For most of human history, homosexuality has been condemned on three grounds: that it is a sin, a crime, and a sickness. Despite the emergence in recent decades of gay-affirming scriptural exegeses, many major religious denominations continue to regard homosexual acts, if not the homosexual inclination itself, as immoral. As to the second rationalization, only in 2003, with the Supreme Court case Lawrence v. Texas, was gay sex decriminalized across the United States, thereby lifting the menace of legal sanction that had long shadowed gay lives. And thirty years earlier, a similar liberation had taken place when the stigma of mental illness was officially disassociated from same-sex attraction.

For this latter advance in human understanding, we largely have Frank Kameny to thank. A Harvard-trained astronomer fired from his job in the Army Map Service in 1957 because of his sexual orientation, Kameny was the first person to challenge the federal government over its anti-gay discrimination policies. Understanding that the rationale for barring highly qualified homosexuals like him from public service rested not only upon the McCarthyite claim that they were liable to subversion, but also that they were mentally unfit, he took it upon himself to change the scientific consensus. Kameny’s most consequential insight as an activist was that it was not the homosexual who is sick, but rather the society that deems him so.

“The problems of the homosexual stem from discrimination by the heterosexual majority and are much more likely to be employment problems than emotional problems,” Kameny wrote in a 1969 letter to Playboy, responding to an article that advised “therapeutic methods” for treating the male homosexual. (One suggested method entailed reading said magazine not for the articles but the pictures.) Doctors “would be of greater service to the harassed homosexual minority,” Kameny concluded, “if they ceased to reinforce the negative value judgments of society and, instead, adopted a positive approach in which therapy for a homosexual would consist of instilling in him a sense of confident self-acceptance so he could say with pride, ‘Gay is good.’”

Published the same year as the Stonewall uprising, at a time when even most liberals were inclined to view homosexuality as an affliction (albeit one whose sufferers deserved pity rather than prison sentences), these were radical words, wholly at odds with the long-settled convictions of the psychiatric establishment. In the first edition of its definitive Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), published in 1952, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) listed homosexuality alongside other “sexual deviations” like pedophilia and exhibitionism. The diagnosis was, in the words of the National Gay Task Force, the “cornerstone of oppression” for homosexuals. It was also a source of untold personal torment. During the postwar era, some of the common techniques used to “cure” homosexuals of their supposed illness were electroshock treatments and aversion therapy. The latter, administered by medical professionals, would sometimes entail a patient being injected with a nausea-inducing element and made to view sensual images of members of their own sex. In 1970, when a gay undergraduate at no less a cerebral and rational place than the Massachusetts Institute of Technology tried to organize a dance for Boston-area gay students, the dean of student affairs turned him down. Homosexuality, he told the school newspaper, was “a disease.”

To such castigatory generalizations about the sanity of him and his fellow gays, Kameny had a bold retort. “Yes, we are sick—we are sick of your manipulation and exploitation of us,” he declared at a 1971 meeting of the APA. He proceeded with a list of eight demands, one of which was that “homosexuality be removed permanently from the psychiatric list of diseases.” In conclusion, Kameny defiantly called for “treatment of the oppressing society instead of the attempted treatment of us, the oppressed homosexual.” Two years later, thanks to the fervent lobbying of Kameny and other gay activists working in tandem with sympathetic heterosexual members of the APA, the nation’s leading organization of mental health experts, removed homosexuality from the DSM. Soon thereafter, the American Medical Association, the American Psychological Association, and the American Academy of Pediatrics, among other professional groups, explicitly stated their opposition to efforts aimed at changing people’s sexual orientation. (The battle over the APA designation is the subject of a forthcoming documentary film, Cured.)

While the APA’s 1973 decision was a momentous and under-appreciated moment in the history of gay rights (as significant, if not more so, than Stonewall), it did not mark the end of organized attempts to “convert” homosexuals into heterosexuals. That same year, a man named Frank Worthen started an organization called Love in Action (LIA), founded, in the words of one of its leaders, “as a Christian ministry to prevent or remediate unhealthy and destructive behaviors facing families, adults, and adolescents, which includes promiscuity, pornography and homosexuality.” With one of the three traditional condemnations of homosexuality—sickness—now obviated by the medical establishment, the destructive effort to make gay people straight would be smuggled in under the rubric of another: sin.

Advertisement

*

The evolution of conversion therapy from prevalent medical practice to pseudo-scientific religious scam is the subject of a legal white paper entitled The Pernicious Myth of Conversion Therapy: How Love in Action Perpetrated a Fraud on America. Written by a team of lawyers from the firm McDermott Will & Emery LLP, it has been drafted on behalf of the Mattachine Society of Washington, D.C. One of the earliest gay rights activist groups (co-founded by Kameny in 1961), it has today been reconstituted as an organization devoted to “archive activism,” which uses archival material to illustrate the ways in which American institutions persecuted gay people. The publication of the report is timed to coincide with the release of the film Boy Erased, based on the real-life experiences of a young man forced by his evangelical Christian parents to undergo conversion therapy in 2004 at a Memphis facility administered by LIA.

The report traces the origins of modern-day conversion therapy to St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, D.C., originally known as St. Elizabeths Hospital for the Insane. Founded by social reformers to provide humane treatment for the mentally ill in 1855, its most famous patients have included Ezra Pound and John Hinckley Jr., Ronald Reagan’s would-be assassin. Beginning in 1948, when the United States Congress (which then governed the District of Columbia) passed a “sexual psychopath” act criminalizing gay behavior, the hospital became a repository for gay men and women who ran afoul of the law. In the words of Mattachine President Charles Francis, St. Elizabeths operated as a “shadowy think tank of psychiatry and policy behind much of the bad science, barbaric treatments, ‘cures’ and investigations of an era.”

According to the statute, patients would remain at the hospital until its leadership determined they had “sufficiently recovered so as not to be dangerous to other persons.” St. Elizabeths’ senior psychiatrist from the 1920s through the 1960s was Dr. Benjamin Karpman. “Chasing all of the homosexuals out of one city (even assuming such a thing were possible) would not solve the problem of homosexuality, any more than chasing all of the thieves out of one city would solve the problem of dishonesty,” he explained in a 1954 memorandum. “Psychiatry should take time out from discussing homosexuality as an individual ‘disease’ and offer a constructive plan for dealing with it as a social problem.” Although he supported the decriminalization of same-sex sodomy, which put him at odds with the city’s overzealous police department and its congressional overlords, Karpman nonetheless saw homosexuality as a scourge in need of treatment. (Considering how his pathologizing of homosexuality would later be re-appropriated by evangelical Christians, Karpman’s skepticism toward religious injunctions against same-sex desire is ironic. “The fundamental religious objection to homosexuality is not that it is immoral, but that it is sterile,” he wrote. “The only ultimate concern of religious institutions is their own economic preservation. ‘Sin’ is simply their stock in trade; they can no more do without it than a grocer can do without canned soup.”)

For those who wished to treat themselves in the comforts of their own home, the Farrall Instruments Company of Grand Island, Nebraska, marketed the self-administered “Visually Keyed Shocker” a disturbingly cheery advertisement for which is included in the white paper’s appendix. “Aversive conditioning has proven an effective aid in the treatment of child molesters, transvestites, exhibitionists, alcoholics, shop lifters and other people with similar problems,” reads the catalogue description, published the same year as the APA’s decision to remove homosexuality from the DSM. “In reinforcing heterosexual preference in latent male homosexuals, male slides give a shock while the stimulus relief slides of females do not give a shock.” Customers could also purchase a “penile expansion monitor” to measure their progress.

Condemnation by the medical establishment eventually discouraged the widespread use of such quack methods to “cure” homosexuality, at least among licensed medical professionals. But it would take far more than a secular edict to erase millennia-old, deeply ingrained, religiously inspired societal stigma against homosexuality. The APA’s 1973 decision, the white paper notes, came amid the sexual revolution and women’s movement, events that “triggered fear and panic in the hearts of some members of society.” Devoid of a medical diagnosis, the attempt to convert homosexuals persists, albeit dressed up in religious garb. Though claiming a basis in prayer rather than science, conversion therapy was “rooted in the same misconception earlier embraced by the medical community and the federal government: the idea that homosexuality was wrong and needed to be cured.”

Advertisement

The second half of the white paper traces the ordeal of LIA, which became the subject of international outcry after a plaintive blogpost written by a sixteen-year-old boy shipped off by his parents to one of the group’s re-education camps went viral in 2005. “If I do come out straight, I’ll be so mentally unstable and depressed it won’t matter,” the young man wrote. Under public pressure, the Tennessee Department of Children’s Services and several other state entities launched investigations of LIA, but given that the boy was a minor, and that LIA was not advertising itself as a mental health institution (in which case it would need to obtain a license from the state), there were no legal grounds on which to penalize the organization. (Visiting one such program in North Carolina several years ago on a reporting assignment, I asked a young participant about his introduction to the “homosexual lifestyle.” My heart sank at his reply: “I worked in retail.”)

Opponents of conversion, however, eventually won another sort of victory. In an ending so common as to be unremarkable, the director of Love in Action resigned, declared himself happily homosexual, renounced his past work, and married his same-sex partner. “No amount of religious indoctrination can change a person’s sexual orientation,” John Smid told the authors of the white paper:

We were playing with people’s minds… We were working in a genre that we were not educated or equipped to work in. And if we were educated and equipped, we could not have gotten a license to do it. The mental health professionals and organizations all clearly stated that homosexuality is not a mental disorder. There should not be an attempt to change that in a person’s life.

Smid says that, in his three decades of working in the so-called “ex-gay” movement, he never saw anyone “who experienced a change from homosexual to heterosexual.” He has since contributed an archive of personal papers, amassed over his long career with LIA, to the Mattachine Society, which in turn donated them to the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian Institution.

According to the Williams Institute, an LGBT think tank, some 700,000 LGBT people in the United States have been subjected to conversion therapy, and 57,000 children will be sent to such programs before the age of eighteen. A dozen states including the District of Columbia currently prohibit state-licensed mental health professionals from practicing conversion therapy techniques on minors. Ever since 1973, however, when the APA removed homosexuality from its list of mental disorders, conversion therapy has largely been the remit of religious ministries, which are, of course, free to tell parishioners whatever they wish about the ways of the universe, the sinfulness of same-sex attraction included. The Institute notes that existing state-level bans permit clergy to engage in conversion therapy practices provided they “do not hold themselves out as acting pursuant to a professional license.”

One creative way of addressing this loophole is to treat conversion therapy as a form of consumer fraud. That is the approach of the Therapeutic Fraud Prevention Act, a bill introduced in 2017 in the US Senate by Patty Murray of Washington, which would prohibit both the provision of conversion therapy “for compensation” and advertising that claims it will change one’s sexual orientation. In California, a gay rights group is suing a therapist on behalf of a lesbian who spent $70,000 over five years for “therapy based on fraudulent, harmful lies,” which led her to believe that her sexual orientation could be changed. But given all the promises organized religions make to their flocks—a right enshrined in the First Amendment—it’s hard to see, legally, how prohibitions on “praying the gay away” would pass muster.

Nonetheless, increased scrutiny of conversion therapy—in particular, harrowing stories from “survivors” about their emotional torture at the hands of those promising to “cure” them—is likely to have the same long-term effect on this “pernicious” practice as similar exposés have had on the cult known as Scientology. To be sure, that dangerous sect still attracts a handful of followers. But it would attract a lot more were it not the subject of frequent, critical media attention (and biting satire).

Reflecting on the long struggle against conversion therapy, I am reminded of the answer Frank Kameny gave when I asked him what had been the most important lesson he had learned in life. “The one thing in which I have absolute faith is the validity of the product of my own intellectual processes,” the famously stubborn Kameny told me in a 2010 interview, a year before his death at the age of eighty-six. “Therefore, if society and I, or the world and I, differ on something, I’ll give them a second chance to make their point, and I’ll take a second chance to make my point. And if we both still differ, there will be a war. And I tend not to lose my wars.”