Do the beliefs we hold about literature add up to something consistent and coherent? Or are they little more than random pieties? Take two crucial notions I heard repeatedly last year. First, that in a fine work of literature, every word counts, perfection has been achieved, nothing can be moved—a claim I’ve seen made for writers as prolix (and diverse) as Victor Hugo and Jonathan Franzen. Second, that translators are creative artists in their own right, co-authoring the text they translate, a fine translation being as unique and important as the original work. Mark Polizzotti makes this claim in Sympathy for the Traitor (2018), but any number of scholars in the field of Translation Studies would agree.

Can these two positions be reconciled? Doesn’t translating a work of literature inevitably involve moving things around and altering many of the relations between the words in the original? In which case, either the original’s alleged perfection has been overstated, or the translation is indeed, as pessimists have often supposed, a fine but somewhat flawed copy. Unless, that is, we are going to think of a translation as a quite different work with its own inner logic and inspiration, only casually related to that foreign original. In which case, English readers will be obliged to wonder whether they have ever read Tolstoy, Proust, or Mann, and not, rather, Constance Garnett, C.K. Scott Moncrieff, or Helen Lowe-Porter. Or more recently, Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, or Lydia Davis or Michael Henry Heim.

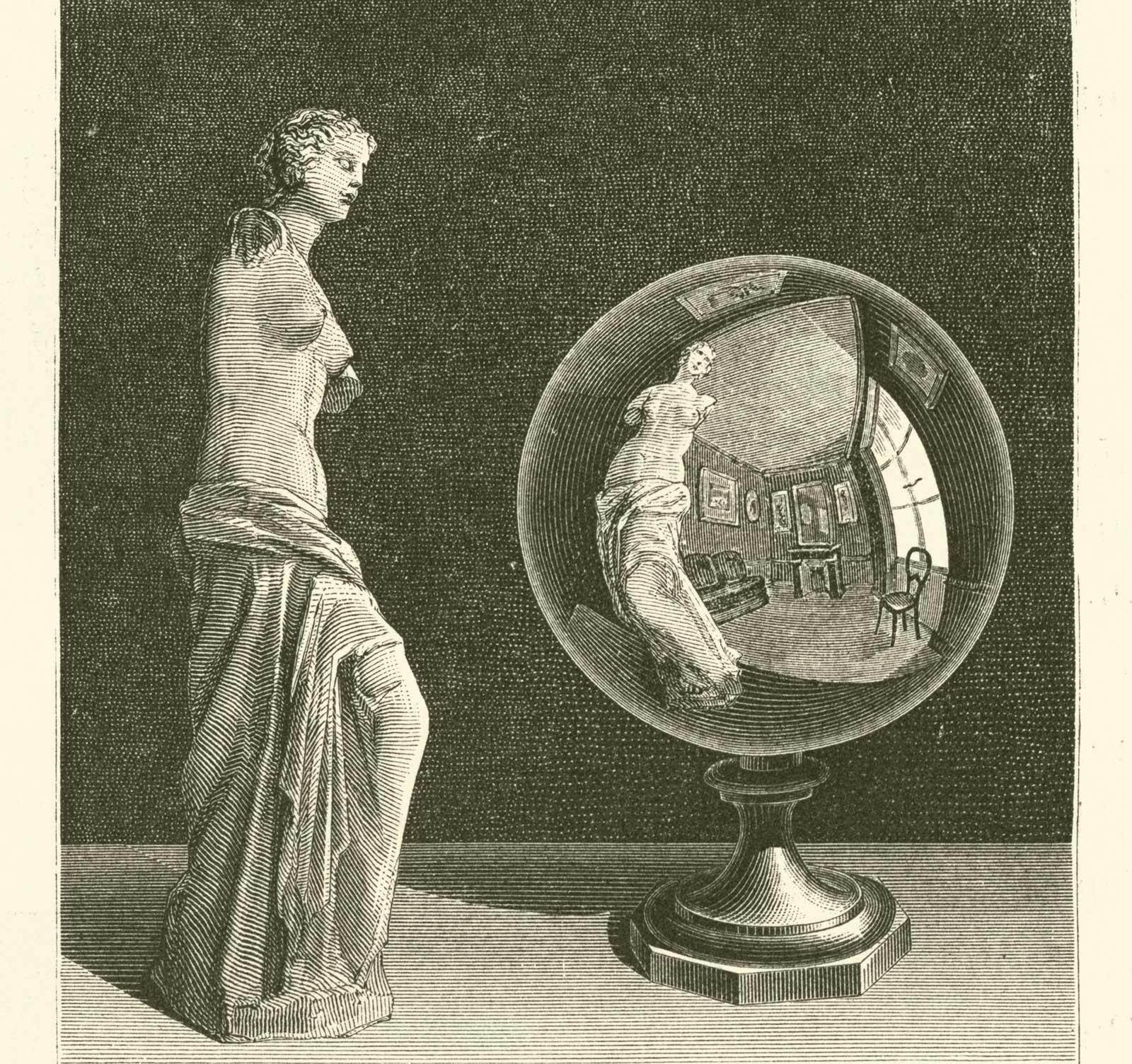

How perplexing. One of the problems in this debate is that most readers are only familiar with translated texts in their own languages. They cannot contemplate the supposed perfection of the foreign original, and when the translation delights them, they rightly thank the translator for it and are happy to suppose that the work “stands shoulder to shoulder with the source text,” as Polizzotti puts it. It makes these readers’ own experience seem more important. Alternatively, when they rejoice over the perfection of Jane Austen, Henry James, or F. Scott Fitzgerald, they do not see what foreign translations have done to the work as it travels around the world.

Let’s consider a couple of examples, one from English into Italian and one from Italian into English, and try to get a clearer idea of what actually happens between original and translation, untroubled by polemics or special pleading. Here is Henry James opening his fine story “The Altar of the Dead” (1895):

He had a mortal dislike, poor Stransom, to lean anniversaries, and loved them still less when they made a pretence of a figure. Celebrations and suppressions were equally painful to him, and but one of the former found a place in his life. He had kept each year in his own fashion the date of Mary Antrim’s death. It would be more to the point perhaps to say that this occasion kept him: it kept him at least effectually from doing anything else. It took hold of him again and again with a hand of which time had softened but never loosened the touch. He waked to his feast of memory as consciously as he would have waked to his marriage-morn.

We’re struck at once by the curiosity of “lean anniversaries” and the rather unexpected “pretence of a figure.” The story of the fiancée’s death allows us to realize that “lean” has the sense of unhappy (as in the lean and fat cows of Pharaoh’s dream), while the account of Stransom’s obsession adds to this leanness the idea of the girl’s softening hand holding him from beyond the grave. At this point, the choice of “mortal” right at the beginning and “pretence of a figure” also make sense: it’s as if the various parts of some gaunt, ghostly manifestation were calling to each other beneath the surface of the writing. The cleverness of the three uses of “keep” helps bring them together: Stransom keeps the anniversary, but no, it keeps him, it keeps him from doing anything else, because, in a way, Mary Antrim is not dead. Lean and softly decaying, she is still pretending to figure. And James is having fun. Stransom “wakes” to his “marriage morn,” which is, in fact, a wake and a mourning. And so on. Here is the Italian, by Giulia Arborio Mella, which, with patience, we shall try to understand:

Lui non le poteva soffrire, povero Stransom le celebrazioni scialbe, e ancor più detestava quelle pretenziose. Le commemorazioni lo affliggevano non meno dell’oblio, e una sola trovava spazio nella sua vita: a modo suo, aveva sempre osservato la ricorrenza della morte di Mary Antrim. Ma forse sarebbe più esatto dire che era quella ricorrenza a osservare lui, a tenerlo d’occhio, anzi, al punto da sottrarlo a ogni altra cura. Anno dopo anno lo ghermiva col suo piglio mitigato dal tempo, ma non per questo meno imperioso; e ogni volta, per quel festino di rimembranze, Stransom si destava pronto e consapevole come fosse stato il mattino delle sue nozze.

When I show these two texts to Italian students without saying which is the original, they often imagine it is the Italian. The writing is attractively literary, vaguely pompous, archaic, solemnly fluent. It feels like the kind of things Italians used to write. Paying a little attention, however, we see that there are parts that don’t make much sense. Here is a brutally literal translation of the Italian back into English:

Advertisement

He couldn’t stand them, poor Stransom, those banal/empty celebrations, and he detested pretentious celebrations even more.

The English posited one kind of anniversary/celebration that Stransom dislikes, the unhappy kind, which he dislikes even more when they put on a show; in the Italian, he hates two kinds, empty anniversaries and pretentious ones. This doesn’t really set us up for his obsession with Mary Antrim’s death. Here’s the next sentence, again in my literal translation:

Commemorations pained him no less than forgetfulness/oblivion, and only one found space in his life: in his way he had always observed the anniversary of Mary Antrim’s death.

James’s Stransom found it painful to commemorate an unhappy anniversary and equally painful to suppress it, to pretend it wasn’t occurring. The Italian has Stransom equally pained by commemorating and forgetting. It’s not clear how this could be; once something is forgotten, it ceases to be painful. Stransom’s problem is precisely that he can’t forget. Let’s take the remaining two sentences in one chunk, noticing the problem the translator has in finding an equivalent for James’s game with “keep,” the disappearance of the suggestion of decay in the softening hand, and the inevitable loss of fun with “waked” and “morn.”

But perhaps it would be more exact to say it was the anniversary observed him, kept an eye on him rather, to the point of subtracting him from any other concern. Year after year, it clutched him with a grip mitigated by time, but no less imperious for that; and every time this feast of remembrance came round, Stransom woke up ready and conscious as if it had been the morning of his wedding day.

In many ways, the Italian version is an excellent translation. Certainly, many Italians will have enjoyed reading it. Better to have it than not. But it doesn’t reproduce the internal tension and apparently easy patterning of the English, that crucial meshing of a language’s possibilities with an author’s imagination that gives us literature. The Italian translator is playing catch up as best she can, tossing in melodrama (“clutch… imperious”) where James only has the quiet, but deadly effective “keep.” Perhaps another translator might have given the first lines more faithfully and just as fluently, but there would still have been moments when the writing wasn’t so intensely allusive and interconnected. This is simply because one is translating rather than writing.

Now the other way around. Here is the great Giovanni Verga opening the short story “I galantuomini” (1883).

Sanno scrivere—qui sta il guaio. La brinata dell’alba scura, e il sollione della messe, se li pigliano come tutti gli altri poveri diavoli, giacché son fatti di carne e d’ossa come il prossimo, per andare a sorvegliare che il prossimo non rubi loro il tempo e il denaro della giornata. Ma se avete a far con essi, vi uncinano nome e cognome, e chi vi ha fatto, col beccuccio di quella penna, e non ve ne districate più dai loro libracci, inchiodati nel debito.

This time, let’s look at the translation straight away. This version, by G.H. McWilliam, is entitled “Bigwigs”:

The trouble is, they know how to write. They’re made of flesh and blood like the rest, so like any other poor devil they put up with the hoar-frost on a dark morning and the dog-days at harvest time, so as to keep watch on their workers and make sure they’re not wasting their time and robbing them of a day’s wages. But once they get their claws into you, they jot down your name, surname and parentage with those pens of theirs, and you never get out of their grubby little books, you’re in debt up to your ears.

Like the Italian translation of James, this looks pretty fluent and readable. Of course, the word “Bigwigs” shifts our perception of these men quite a distance. The English term is always disparaging and has fallen into disuse; the Italian “galantuomini” is alive with antithetical energies; it means gallant men, honourable men, but also possibly and simultaneously, criminals, mafia, bosses—“gallant,” that is, within an abhorrent moral code. The Italian begins “Sanno scrivere—qui sta il guaio” (They can write, there’s the rub). Readers are not used to hearing this kind of thing; how on earth can knowing how to write be a problem? The English opening, “The trouble is…” is weaker. But that is an issue with this particular translation and surely not absolutely necessary.

Advertisement

There follows, in the Italian, a classic example of what linguists call “dislocation”: that is, the two objects of the verb “pigliarsi” (suffer, feel, take) are shifted to the beginning of the sentence, before the subject or verb. This is standard behavior in colloquial Italian and is often accompanied by a device called anaphora, in which the object is then repeated, as it were, in pronoun form. I’ll give a literal translation following the Italian syntax. Watch how this organization sets Verga up for the repeat of the word “prossimo,” meaning neighbor or fellow man in the Biblical sense of “Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself.” In fact, “prossimo” is used in the sense of ‘neighbor’ only when recalling Christ’s commandment.

The frost on a dark dawn, the hot sun of harvest time, they feel them like every other poor devil as they’re made of flesh and blood like their neighbor, to go and check that their neighbor is not stealing their time and the day’s money.

This isn’t fluent English and our translator was right to move things around. But the Biblical reference seems crucial. The idea of loving one’s neighbor is evoked exactly as these men seek to control and exploit their neighbors. It’s worth noting that like the syntax, the words used—“pigliarsi,” “carne,” and “ossa”—all have a colloquial, low-register feel that makes the text intensely homogeneous and suggests that the speaking voice is close to the men being watched over, rather than the landowners who are watching. All this, however, is nothing to the problem of the metaphor Verga sets up in the next sentence, clinching his paragraph with an image that explains the claim of the opening few words. Again, I’ll give a literal version:

But if you have to do with them, they’ll hook you name and surname, and the person who made you, with the nib of that pen, and you’ll never extricate yourself from their horrible books, nailed in debt.

The “problem” with knowing how to write, it turns out, is that it allows the rich to nail the poor by recording their names, and the names of “who made you” (your parents) in their debtors’ books. It’s all rapidly and effortlessly delivered in the Italian, with the harsh vocabulary (“uncinano,” “libracci,” “inchiodati”) again at one with the impression of a local speaking voice. The English is idiomatic enough with its “get their claws into you” and “up to your ears in debt,” but it has lost the strong metaphor of the pen as an instrument for capturing and torturing the neighbor you were supposed to love.

These are just two translations of a couple of paragraphs of fine literature. No doubt, both could be bettered. But they are fairly ordinary examples of what happens in the translation process. It is not that the original has achieved some mystical perfection, but it is marshalling syntax, lexical choices, rhetorical devices, and cultural context—everything, in short—to conjure up that density of possible meaning combined with felicity of expression that gets us so excited when we read good literature.

The translation does its best, and if the content and plot are strong, the reader will be drawn in and not feel the loss, since he or she can’t know what is being missed. On its side, the translation has the advantage of exoticism: we may be fascinated by Verga’s Sicily precisely because we don’t know much about it. For its part, the original can call on the more potent resource of recognition; this is our world described in our tongue, we can’t deny it.

To return to our original questions: an original we might now say is not so much a perfect text as one that is truly embedded in the culture that produced it. A translation can indeed be creative and “important,” but it is the creativity of astute accommodation and damage limitation, the “importance” of allowing as much as possible of that original to happen in the translator’s culture. To imagine, however, that Henry James could ever be to the Italians what he is to us, or Giovanni Verga to us what he is to Italians, is nonsense.

An earlier version of this essay misidentified the translator Constance Garnett. It also misstated Pharaoh’s dream as Nebuchadnezzar’s. The piece has been updated.