On Christmas Eve 1959, the revolutionary psychiatrist Frantz Fanon went to a party at the home of his secretary, Marie-Jeanne Manuellan, in Tunis, where he was working as a spokesman for the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN). Fanon had invited himself over, and Manuellan could hardly say no to her boss, but she was dreading his appearance. She had been taking dictation for his study of the Algerian war of independence, A Dying Colonialism, and found him so severe, and so unfriendly, that she nicknamed him “The Sadist.” “Dance in front of Fanon?” Manuellan writes in her recent memoir, Sous la dictée de Fanon. “It wasn’t possible… But how could I tell him, ‘Stay home!’ He was going to spoil the evening for us.”

To her “great astonishment,” Fanon was the life of the party. “Smiling, truly happy, cracking jokes,” he picked up a guitar, sang West Indian songs, and chatted till the small hours with her husband about jazz and blues. Music brought out a levity, a warmth, in Fanon that Marie-Jeanne had never before noticed.

Fanon was not a musician, but he loved what he called the “charge” of words, their power to move, and not merely persuade, and he was no stranger to improvisation. In her memoir, Manuellan describes taking dictation from him: “Fanon didn’t have any paper in hand. He would walk and ‘speak’ his book as if his thought shot smoothly from his steps, from his body’s rhythm, with very rare interruptions or reprises.” Both A Dying Colonialism and his 1961 anti-colonial manifesto The Wretched of the Earth originated, in effect, as spoken word performances, with Manuellan the sole member of the audience.

In his 1959 lecture at a congress of black artists and writers in Rome, Fanon drew upon a musical example to illustrate his vision of a revolutionary culture. “On National Culture”—later published as a chapter of The Wretched of the Earth—celebrated the defiant “new humanism” of bebop, which had grown out of “the inevitable, though gradual, defeat” of segregation. Having cast off their role as entertainers for the white man, bebop musicians were shaping their own destiny as artists. In “fifty years or so,” Fanon predicted, the “type of jazz lament hiccuped by a poor, miserable ‘Negro’ will be defended by only those whites believing in a frozen image of a certain type of relationship and a certain form of negritude.” Black American jazz, with its commitment to artistic independence and innovation, was, for Fanon, an exemplary practice of cultural freedom, a model for the wretched of the earth in their efforts to invent a new, emancipated identity.

In times of revolutionary upheaval, he reminded his audience in Rome, “tradition changes meaning,” since it is “fundamentally unstable and crisscrossed by centrifugal forces.” The liberation struggle, he insisted, would not “leave intact either the form or substance of the people’s culture.”

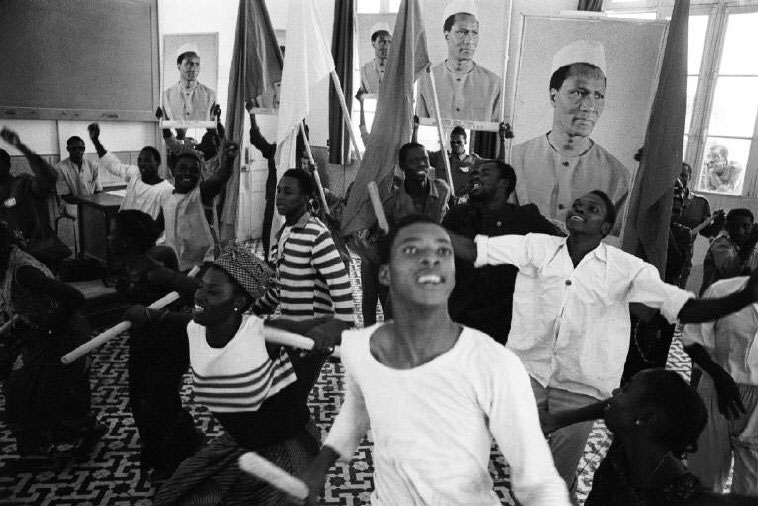

Fanon died in 1961, less than a year before Algerian independence. His critique of cultural traditionalism was mostly ignored by the FLN leadership, which turned away from his revolutionary modernism. But Fanon’s vision of a revolutionary culture received a spellbinding tribute in Algiers in the summer of 1969, when Nina Simone, Miriam Makeba, the free jazz saxophonist Archie Shepp, the Beat poet Ted Joans, the Black Panthers, and representatives of various national liberation movements arrived for the Pan-African Festival—the Woodstock of the Third World. “We are still black and we have come back. Nous sommes revenus,” Shepp declared from the stage, in a performance with a group of Tuareg Berber musicians. “Jazz is an African power! Jazz is an African music!”

It lasted ten days; nothing of its ambition or scale was ever repeated. (The American activist Elaine Mokhtefi, one of the organizers, gives a moving account of the festival in her new memoir, Algiers, Third World Capital: Freedom Fighters, Revolutionaries, Black Panthers.) But the spirit of Algiers in 1969, which heralded a more expansive, collective freedom than Serge Gainsbourg’s libidinal anthem “69 année érotique,” inspired a vast and sprawling cultural movement. The movement has received a fabulous musical tribute from the French rapper known as Rocé, an anthology of twenty-four tracks, recorded between 1969 and 1988, with the explicitly Fanonian title, Par les damné.e.s de la terre, “by the wretched of the earth.” Anyone who has listened to its nearly eighty minutes will find it hard to imagine that anyone could ever have asked whether the subaltern can speak, a question famously posed by the literary theorist Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. These “voices of struggle,” as the subtitle calls them, speak (and sing) with radiant, unpretentious, unstoppable eloquence—and with a seductive confidence that, whatever setbacks they encounter, history is on their side. They remind us that Third World liberation wasn’t simply a cause; it was a romance. Yet Rocé’s purpose isn’t to rekindle a love affair, much less to mourn its passing. Par les damné.e.s de la terre is conceived as a musical history from the bottom up, addressed to contemporary listeners of French hip hop who, in his view, have been deprived of knowledge of their cultural heritage. As Rocé explains in his “note of intention”:

Advertisement

I’m part of the generation that saw the rise of French rap, and along with it, a real craze for this music created by the children of second and third generation immigrants. But I wanted to go beyond rap, to dig deeper into Francophone artists who convey a message of poetic urgency, of sensitive poetry on the edge, committed to a cause despite itself, because their environment gives them no choice… Many artists present in this collection didn’t have the good fortune of finding a receptive audience at the time; I think that current issues around migration and identity will give special resonance to these words and this music.

Rocé, who is forty-one, has been a passionate reader of Fanon since he discovered Black Skin, White Masks as a teenager. Fanon’s 1952 study of racism in France captured the feelings of alienation that he’d experienced as a young man of color in Paris. (Rocé’s mother is from Algeria’s small black community.) He was equally struck by The Wretched of the Earth, whose depiction of a colonized world “cut in two” by “the barracks and the police stations” reminded him of Paris and its banlieues: “The banlieues in France are managed today like the former colonies, with the symbolic barriers of the police. But because of the universalism of the left here, we’re supposed to pretend that race doesn’t exist.” French hip-hop—in large part the creation of young men and women from black and Arab families—helped break the wall of silence and denial around the problem of race in France.

Par les damné.e.s de la terre, which doubles as a history of French rap’s hidden ancestry, is an album teeming with words. Reciting his poem “Il est des nuits” (“There are nights”), Léon-Gontran Damas, one of the founders of the Négritude movement, evokes with grave, sonorous beauty,“the nameless nights, the moonless nights” of his days in Paris as a poor student from French Guiana. (As Amiri Baraka remarked, Damas wrote “literally poems to be sung.”) We also hear directly from Ho Chi Minh and from General Vo Nguyen Giap, who, in a 1976 interview in Algiers, declared that “nothing is more precious than independence.” But even as Rocé pays his respects to such legendary Third World revolutionaries and writers, his project focuses on music by artists who have either slipped into obscurity or who were hardly known in the first place: the B-sides of the revolution. For all its insurrectionary fervor, most of the music he selected is more lyrical than didactic. Rocé’s understanding of “independence” has less to do with the liberation of territory than the liberation of the imagination.

To listen to this anthology is to be struck by the sheer variety of genres through which the Francophone “wretched of the earth” expressed their rebellious energies: Berber songs of exile, rock, folk, free jazz, reggae, Afro-pop, even—in the singer-songwriter Pierre Akendengue’s lilting “Le trottoir d’en face,” a flâneur’s diary of street life in Gabon—an African gloss on the French chanson tradition of Piaf, Brassens, and Brel. Cross-pollination, collage, and “appropriation” were the order of the day. But it’s not just the range of forms, or the interplay of tradition and innovation, that seizes the attention; it’s the sense that the struggles invoked by the title were shared and overlapping, part of a transnational project of liberation whose ultimate goal was the decolonization of the Francophone world, including France itself. That goal proved elusive. Independence led to new forms of oppression in countries liberated from the French empire, while the French establishment still shies from acknowledging the crimes of imperialism or, for that matter, the existence of French multiculturalism, the empire’s bastard offspring. (Last November, a group of eighty French intellectuals published a vitriolic letter in Le Point denouncing postcolonial studies as a threat to Republican values, even as a form of “intellectual terrorism.”) Yet these artists succeeded in creating a common culture of revolt, an anti-colonial internationalism “made of fluid exchanges and mutual borrowings,” as Robert Malley has argued in his study of Third Worldism, The Call from Algeria.

They also helped remake the French language, a language their ancestors had been forced to speak, by smuggling into it the subjectivity, the accents and the speech of the Republic’s imperial subjects. In his 1948 essay on the Négritude poets, “Black Orpheus,” Jean-Paul Sartre argued that the French language was a double-edged sword for black poets who, even as they rejected French colonialism, were forced to “rely on the words of the oppressor’s language… this goose-pimply language—pale and cold like our skies… this language which is half dead for them… Like the sixteenth-century scholars who understood each other only in Latin, black men can meet only on that trap-covered ground that the white man has prepared for them: the colonist… is there—always there—even when he is absent, even in the most secret meetings.” But the performers on Rocé’s anthology suggest a more hopeful story. As the Algerian novelist Kamel Daoud has written, the process of decolonization produces its own “strange creole,” a new language that grows out of the imposed language only to turn it to radically different expressive and political ends. Par les damn.é.e.s de la terre is an exhilarating tribute to the revolutionary beauty of this strange creole.

Advertisement

Rocé’s definition of “the wretched of the earth” is refreshingly supple, referring not only to people colonized by the French, but also factory workers and victims of fascism. There are two tracks by the Groupement Culturel Renault, a psychedelic band formed in the early 1970s by anarchist militants in the Renault factory in Boulogne–Billancourt who combined the deadpan pose of Serge Gainsbourg and black American soul with denunciations of workplace alienation. Rocé has also included an otherworldly tribute to the First Nations of Quebec by the poet Claude Péloquin, who grumbles in Quebécois over the whirling, freaky sounds of “The Machine,” a synthesizer created by his partner, the electronic musician Jean Sauvageau. “Monsieur l’indien” (1972) is a gorgeously paradoxical work, using modern technology in defense of a pre-industrial civilization threatened by what Walter Benjamin called the “storm” of progress, symbolized by the sound of the high-speed train we hear at the end.

The inclusion of “Monsieur l’indien” may raise some eyebrows, since neither Péloquin nor Sauvageau is a member of the First Nation. It may be for, but it’s certainly not by, the “wretched of the earth.” Péloquin himself dismissed the idea that their work was an act of solidarity. “We were beyond the revolution,” he said. “We were about consciousness. We were closer to the Fluxus Group, and to people like Ferlinghetti.” But the lines between the counterculture and Third Worldist politics were porous in those days, and one was often a gateway drug to the other. You don’t have to be persuaded by the politics of “Monsieur l’indien” to be hypnotized by it, which is probably why it made the cut. This is the anthology of an artist, not a historian, and it expresses Rocé’s love of revolutionary sounds as much as his commitment to revolutionary politics.

Although Par les damné.e.s. de la terre was intended as an inspiring soundtrack of resistance, it also displays a strong undercurrent of disappointment; a thread of postcolonial melancholy runs through the album. There are, not surprisingly, a number of tracks about the plight of Arab and West Indian laborers in France, but Western racism isn’t the only target here. A number of tracks describe the aborted promise of independence in countries ruled by predatory elites, the “native bourgeoisie” who Fanon warned would confiscate power after the overthrow of colonialism. In the most heartbreaking track on the album, “Le mal du pays” (“homesickness”), recorded in 1984, the exiled Haitian singer-songwriter Emmanuel “Manno” Charlemagne evokes the terror of the Duvalier dictatorship and the Tonton Macoute paramilitaries, wondering if he will ever return to “sing of liberty.” Ten years later he did, and in 1995 he was elected mayor of Port-au-Prince. But he was forced into exile once again, and died in Florida in 2017.

In “Les Vautours” (“The vultures”), recorded in 1978, Abdoulaye Cissé, a guitarist and singer-songwriter from Burkina Faso, describes a continent that fell into permanent exile from itself. The vultures are the traders and colonizers who diverted Africa from what might have been its natural path. Before their arrival, he sings over a warm, Afro-Cuban groove, “the African sky was so serene, the soil of Africa was at peace… since that day men have been fighting… the people of Africa have been looking for what they have lost, and at night around the fire, the sound of the drums rises in the sky, in search of the treasures the vultures took with them.” Cissé held a number of positions in the revolutionary government of Thomas Sankara, and conducted its choral groups, until Sankara was assassinated in October 1987. The time of the vultures had never ended.

*

The idea for Par les damné.e.s de la terre arose by chance, in a record shop. The owner, Aurélien Delval, a childhood friend of Rocé’s, played him a spoken-word piece recorded in 1970 by Alfred Panou, an actor, filmmaker, and poet from Benin. Panou, who had played a revolutionary in Jean-Luc Godard’s Weekend, was staging a play called Black Power, a setting of texts by Angela Davis, Amiri Baraka, and Stokely Carmichael, when Pierre Barouh of Saravah Records invited him to record something with the Art Ensemble of Chicago, the great American free-jazz band, which had decamped to Paris for the year. Just before going to bed that evening, Panou scribbled a poem, “Je suis un sauvage” (“I am a savage”), in a fit of automatic writing; he recorded it with the Art Ensemble the next day at a studio in Montmartre.

Panou had discovered Fanon when he came to Paris, and in “Je suis un sauvage,” he offers an outrageous, Afro-surrealist take on what Fanon called “the lived experience of the black man” in white spaces, particularly the encounter with the white gaze. “I am a savage, but not a slave,” Panou proclaims, mocking racists by ventriloquizing their phobias about the black body (“despite my daily shower… my odor stuns the illuminated”) and African cannibalism (“What sauce do you prefer to be eaten with? The state will pay for it!”). Panou was obviously having great fun, as was the Art Ensemble. Malachi Favors’s bass hooks us from the moment the track begins. The saxophonists Roscoe Mitchell and Joseph Jarman play stately, unison lines on reeds, around which Lester Bowie performs dancing, mischievous riffs on trumpet. The wit and irreverence of “Je suis un sauvage” floored Rocé. In Panou, who, he discovered, was still living in Paris running a cinema for African films, Rocé felt as if he’d found a French contemporary of The Last Poets: an authentic exponent of spoken-word poetry, an ancestor of French rappers like himself.

Back at the record shop, his friend Delval had another revelation waiting for him: “La Pieuvre” (“The Octopus”), recorded in 1968 by the singer-songwriter Colette Magny, a former typist best known for her 1963 “Melocoton.” Born in 1926, Magny was well known for her covers of jazz and blues songs, and praised as France’s Ella Fitzgerald. But her husky androgynous voice, her taste for songs of torment and anger, and her manner of declaiming as much as singing her lyrics were more reminiscent of Nina Simone. By the late 1960s, Magny had become an outspoken leftist, recording for Le Chant du Monde, a label close to the Communist Party. On “La Pieuvre,” Magny chronicled the grueling working conditions at the Rhodiaceta textile factory in Besançon, where a strike erupted in 1967. (The French filmmaker Chris Marker featured the song in his 1968 documentary about Rhodiaceta.) “You baptized our factories with rocket names / Harsh wine names,” she sings, with accusatory passion. “We work with continuous fires / At more than 30 degrees / And 70 percent humidity / We all become nervous / Our ulcers bloom / our ulcers flourish.” Magny 68, the album on which “La Pieuvre” appeared, was banned by French radio, but Magny refused to retreat. On her 1972 album Répression, whose cover featured a drawing of a black panther, she paid homage to the slain Black Panther party member George Jackson and lashed out at police violence against African-Americans. When Rocé heard “La Pieuvre,” he told himself, “If I can find two tracks like this, there must be more.”

Rocé has an unusually intimate relationship to the history of these “voices of struggle.” Born José Youcef Lamine Kaminsky in 1977 in Algiers, he comes from a family of anti-colonial militants. His father, Adolfo Kaminsky, the son of Russian Jews who had emigrated to Buenos Aires before settling in Paris in the 1930s, fabricated passports for the French Resistance while he was still a teenager. After the war, he forged papers for the Algerian rebels, and later for anti-fascist Greeks, Spaniards, Portuguese, ANC activists, Angolan revolutionaries, and other national liberation insurgents. In his memoir, A Forger’s Life, he says he also provided passports for the militant Jewish group Haganah in its fight against the British in Palestine, but recoiled when he realized the Zionist movement’s intention to create “a state religion, which came down to creating, once again, two categories of population: the Jews and the others.” In the early 1970s, on his first visit to Algeria since independence, he met Rocé’s mother, Leïla, a law student who in her spare time was volunteering for the Angolan national liberation movement. They lived together in Algeria for a decade, before moving with their children to Paris. In his memoir, Kaminsky writes that during his career as a forger, he used “the only weapons at my disposal—technical knowledge, ingenuity, and unshakable utopian ideals” to oppose “a reality that was too harrowing to observe or suffer without doing anything about it.”

Rocé has done much the same, both as a politically aware rapper who has collaborated with free jazz musicians like Archie Shepp and Jacques Coursil, and as the producer of Par les damné.e.s de la terre. But when I spoke with Rocé at his office in Paris last summer, he disabused me of the notion that he’d been steeped in his parents’ experiences of liberation struggles. “Fanon’s books were in the house, but my father never told me about Fanon. That was his history, not mine, and he didn’t want to talk about it. Often when parents change country, they don’t want to start again. They want to move on. So their experiences aren’t really transmitted”—a problem he says the the album was partly designed to redress. As Rocé writes in his notes, “It’s crucial to pass on these moments when anything was possible, so that they infiltrate and disperse the bleak mood that new generations are growing up with.”

Like many French rappers of his generation, Rocé was initially attracted to Fanon because he was “a warrior,” an intellectual who joined a national liberation struggle, but what fascinates him now is “the link Fanon made between the deconstruction of imperialist culture and the creation of a new world.” That link is the implicit subject of one of the album’s most striking tracks, “Complexium,” recorded in 1974 in New York by the singer Dane Belany. “Complexium” is a taut setting of a few lines from a play by the Martinican poet Aimé Césaire, who had been Fanon’s mentor; the piece originally appeared on an album dedicated to Fanon, Motivations. Belany’s story is among the intriguing ones unearthed by Rocé’s project (and recounted in the album’s excellent liner notes by the historians Naïma Yahi and Amzat Boukari-Yabara). The daughter of a Senegalese father and a Turkish mother, educated in Paris, Belany won acclaim in the 1960s as a “sexy jazz singer” who combined the “charms of Paris and subjugation of Harlem.” But at the 1969 Avignon Festival, she experienced an epiphany that radicalized her outlook. Her straightened hair had begun to kink under the sun when a black American jazz musician took a comb to her head, unfurled her curls, and told her, “this is how you should comb your hair.” She became one of the first women in Paris to wear her hair in a towering Afro (featured in a triplicate image on the cover of Motivations), only to find herself insulted on the street. When she moved to New York a few years later, she immediately felt at home in the world of black musicians and artists—notably Ornette Coleman, who became a close friend.

Belany’s producer on Motivations was Raphaël Schecroun, a bebop pianist and drummer who called himself “Errol Parker,” in homage to his two favorite musicians, pianist Errol Garner and saxophonist Charlie Parker. An Algerian-born Jew, Schecroun had played piano with Kenny Clarke and Django Reinhardt in Paris, and attracted the attention of Duke Ellington, who published two of his compositions and encouraged him to move to New York. By the time Schecroun arrived in the city, in the late 1960s, the Black Power revolution was in full bloom, and he embraced its vision of reconnecting with the African motherland. He founded Sahara Records in 1971 and began applying the hand-drumming techniques of North Africa to the Western drum kit. On Motivations, he accompanied Belany on drums, along with two veterans of the loft scene: the tenor saxophonist Dewey Redman, a member of Coleman’s band, who performs on the bagpipe-like musette, invoking the sounds of the Arab East; and the bassist Sirone (Norris Jones), who plays spare chords that punctuate Belany’s melodic lines. Their accompaniment is stark and elemental, a foil for Belany’s vocals. She had recently suffered laryngitis and was in poor voice, but Coleman suggested that she speak the lyrics she couldn’t sing. On “Complexium,” she powerfully recites the monologue of the rebel in Césaire’s play And the Dogs Were Silent:

My name: Hurt.

First name: Humiliated.

My state: a rebel.

My age: the stone age.

Here is the voice of a young woman who has inherited an ancient rage: a reminder that, as Walter Benjamin wrote, the revolt of the oppressed is “nourished by the image of enslaved ancestors rather than that of liberated grandchildren.” Her instrument may be weakened, but she uses it to highly theatrical effect, much as Abbey Lincoln did in her civil rights songs of the early 1960s. As Parker wrote in his liner notes, “This stunning brown-skinned redhead, a singer, composer, actress and dancer… has invented and put together a total form of black musical expression in which elements of poetry, satire and tragedy are coherently blended into African rhythms and free jazz.”

Motivations was banned in Senegal: President Léopold Sédar Senghor, one of the founders of the Négritude movement, considered it subversive, perhaps because of Belany’s dedication to Fanon, a fierce critic of Senghor’s. After returning to Paris, she fell into a long depression and all but lost her voice. Her thrilling cry of revolt, an essential document of Third World free jazz, deserves to be reissued in its own right and in full.

What, ultimately, is the purpose of Par les damné.e.s de la terre? The revolutionary spirit it honors is all but extinguished, not least in France, where the gilets jaunes have been notable for their lack of ideology—and the conspicuous absence of non-white demonstrators. Rocé’s project carries more than a whiff of radical chic nostalgia, which he does little to conceal when he describes the 1960s and 1970s as “an epoch of struggles, of possibility.” Yet Par les damné.e.s de la terre is an unexpectedly moving document, not only because it presents an extraordinary archive of recordings, but also because it illuminates the radical hopes that inspired them. Rocé himself, the son of a left-wing French Jew and a black Algerian Muslim who met at a meeting for the liberation of Angola, would not have existed without these hopes, and the new world they dared to imagine. Par les damné.e.s de la terre is a powerful reminder of what that world sounded like.