A head-scratcher and a mind-bender, The Image Book—the latest film by eighty-eight-year-old Jean-Luc Godard—is gloriously obscure and brutally unpretty, yet lucid and even gorgeous all the same.

In a fabulously eccentric Skype press conference held after the movie’s première at the last Cannes Film Festival, Godard remarked that “most of the films in Cannes this year and in preceding years show what is happening, but very few films are designed to show what is not happening.” The Image Book, he hoped, would show precisely that dimension—in its method if not its subject matter.

Since taking the digital turn some twenty years ago with his magisterial video series Histoire(s) du cinéma, an epic exercise in home-video technology that twisted a question—history of film or film of history?—into a nearly five-hour long Moebius strip, Godard’s movies have been gnarly ruminations on Europe’s cataclysmic past century, the significance of his chosen medium, and, by implication, his own mortality.

Where the young Godard of Alphaville (1965), Pierrot le Fou (1965), and Two or Three Things I Know About Her (1967) was the first and greatest of post-modern filmmakers, the old, irascible, stogie-chomping Godard is akin to the encyclopedic high modernists (Joyce, Pound, Pessoa, Benjamin), shoring up fragments against his ruin. He’s also sui generis, a solitary cosmonaut broken free from the Earth’s gravity and sending back intriguingly garbled transmissions from the edge of the solar system.

Godard’s twenty-first-century films—Notre musique (2004), Film socialisme (2011), and Goodbye to Language (2014)—have been wildly experimental, using iPhone and GoPro cameras, video-synthesizers, and 3-D, even while ransacking his archives for classic cinema images. Composed of visual shards and snatches of dialogue, The Image Book seems entirely fashioned of found material. All the images, some taken from old Godard movies, are second- (or perhaps third-) hand. Everything is obviously mediated, mostly by video, and annotated by the filmmaker’s rasping voice.

A film historian friend was annoyed by the way that Christian Marclay’s twenty-four-hour installation The Clock (2010) played fast and loose with the formats of the clips used in its making. Godard, one of the world’s great cinephiles, is even more cavalier. Images are smeared, stretched, squeezed, subject to high-contrast Fauvist distortions, shaken, slowed down, superimposed, and otherwise degraded. A sense to deterioration is crucial. In a recent interview, Godard’s technical assistant Fabrice Aragno revealed that “Jean-Luc records his voiceover with an old microphone, and we keep all the noise. It’s the mark of time.”

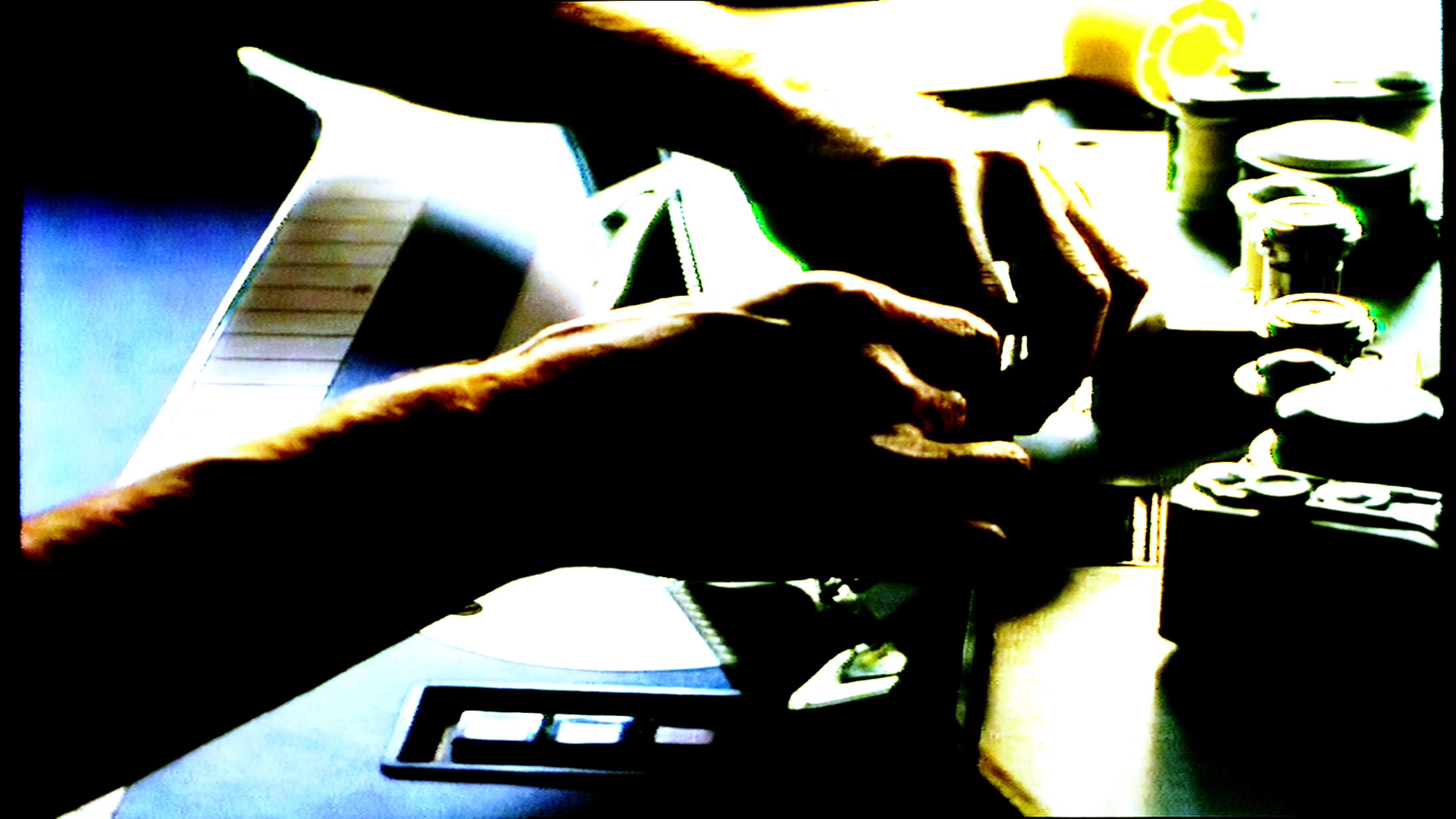

As tendentious as they may seem, Godard’s recent films are not so much arguments as they are assemblages. “One has to think with one’s hands and not only with one’s head,” he twice told the press at Cannes last year. Montage, which is to say juxtaposition, has become Godard’s first principle. One of the first shots in The Image Book is a close-up of the artist making a splice at an editing console. Hands, sometimes fingers pointing upwards, are a recurring motif, reinforcing the movie’s artisanal, as well as didactic, quality.

However polemical Godard may be, the medium is still the message. Fond of wordplay, he makes few concessions to non-Francophones or even the non-French. Where Film socialisme employed gnomic subtitles in what the filmmaker called “Navaho English,” The Image Book severely rations the number of English titles. Almost before it begins, it invokes the venerable French comic-strip character Bécassine, and this cartoon Breton housemaid turns up periodically (and, at least for me, enigmatically) in the midst of the movie’s rapid-fire montage.

Unfamiliar, which is not to say inapt, cultural references abound. The Image Book ends with a quasi-adaptation of the French-Egyptian novelist Albert Cossery’s 1984 political satire Une ambition dans le désert, as yet untranslated into English, in which the leader of an imaginary state, Dofa, the only Gulf emirate without oil, attempts to garner international support by inventing a phantom terrorist organization. Still, so long as one understands Godard’s movie as a hands-on construction, it is not completely inscrutable.

The Image Book is divided into five parts, each with a particular emphasis that nevertheless spills into the rest of the film. The first, “Remakes,” is marked by intimations of nuclear annihilation, including the final shots of the apocalyptic noir Kiss Me Deadly (1955). Other favorites appear: the actor Eddie Constantine, seen in Godard’s Germany Year 90 Nine Zero (1991); a clip showing a confrontation between old lovers Joan Crawford and Sterling Hayden from the Nicholas Ray western Johnny Guitar (1954); a bit from Godard’s own anti-war film Les Carabiniers (1963). There’s a powerful cut from a shark decal on a jet fighter to Spielberg’s monstrous Great White erupting out of the water.

Advertisement

War continues in the second part, “St. Petersburg Evenings.” Here, Godard looks for historical grounding. As compared to “Remakes,” this chapter is a flashback. Godard samples the spectacular Soviet super-production War and Peace (1966–1967) and includes a representation of the French Revolution and documentary scenes of the European landscape after battle, in addition to a clip from his own meditation on the Balkan wars, For Ever Mozart (1996).

The third chapter, named “Those Flowers Between Rails, a Confused Wind of Travels,” in apparent reference to a line from Rilke’s The Book of Hours, is largely devoted to railroad trains—a favorite Leninist trope for onrushing history as well as a frequent metaphor for cinema. The main theme would seem to be mechanization. The fourth part, “The Spirit of Laws,” addresses another sort of machine. Direct yet wide-ranging in its emphasis on the enforcement of civil order, it includes two passages from John Ford’s Young Mr. Lincoln (1939) and instances of transgression, or transgression punished, ranging from gay porn (intercut with a laughing microcephalic from the 1932 movie Freaks), Pasolini’s Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975), Ingrid Bergman put to the stake at the climax of Joan of Arc (1948), and the surreal “The Country’s Going to War” production number from the Marx Brothers’s movie Duck Soup (1933).

The mind may surrender but the eye is engaged. The Image Book is moment-to-moment exhilarating—a work of great beauty and undeniable pathos. More than once, a frozen still comes to life. How to take the spectacle of all these souls trapped by the camera, preserved on video? Bergman is the exemplar. As close to music as Godard has ever gotten, this is less the book than the conflagration of images.

Like the mysterious Bécassine, certain phrases recur throughout, notably “Under Western Eyes,” which becomes the theme of the fifth part, named for Michael Snow’s vertiginous landscape film, La Région centrale (1971). Seemingly as long as the four previous chapters combined, the fifth leaves Europe, crossing the Mediterranean, a body of water shown frequently through the film, into the Maghreb. Is North Africa the world’s central region? Godard samples movie images of the crusades, later colonial wars, and (literally) the Arab street. Ambivalence rules. What is the correct way to frame this world? Godard might be channeling the culture critic Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak when he suggests that the act of representing necessarily involves violence against the represented. Bloody corpses and more bloody corpses are shown. Albert Cossery’s sardonic account of a staged revolution is illustrated with ISIS propaganda videos.

His voice rising in exasperation, Godard rails against all leaders, “Do you think men in power today are anything other than bloody morons?” His last words, however, can be understood as conciliatory or self-deprecating, and might well be a quote from Cossery: “Chatting with a madman is an invaluable privilege.”

Indeed. The Image Book seems about to end with a long list of films and music compositions, but Godard is not quite done. The final few minutes are something of a curtain call. There is slowed-down footage of what appears to be an African royal court, the pointing finger returns, battlefield footage is reprised, and the filmmaker paraphrases Rimbaud (whose image appeared in the fourth chapter) to acknowledge his magpie methodology: “When I speak to myself I speak with the words of another.”

The movie’s final image is shockingly personal—lifted from Max Ophüls’s Le Plaisir (1952), a movie, set in the late nineteenth century, that Godard once anointed the single finest French film since Liberation, with a title, meaning “pleasure,” he considered the greatest in cinema history. The scene, in a Paris salle de danse, depicts a vigorous and vertiginous quadrille. One frenzied dandy faints, falling to the floor. Godard cuts to black, but anyone familiar with the Ophüls film can fill in what follows. The man has been wearing an elaborate face mask. When it is cut away, it reveals a face so old as to seem ancient.

The Image Book opens in New York on January 25 and in Los Angeles on February 15.