The penicillin factory is a sprawling, abandoned complex on the outskirts of Rome. The first thing I noticed when Italian photographer Maurizio Martorana and I visited in November 2018 was the trash. Stacks of T-shirts, juice cartons, plastic plates, clothes racks, and bicycle parts. A path led through a series of buildings, and against every wall was a makeshift shack. At the time, some 500 people, the majority of them African migrants and refugees, lived there amid the debris.

The second floor of the factory was covered with shit—with no working plumbing, people had nowhere else to defecate. The street-side windows looked out on a tennis club. Throughout the grounds were small shops selling beer, toothpaste, and basic cooking supplies. The ground was muddy and contained chemicals and asbestos leftover from the factory’s manufacturing days.

Over the past year, depending on your perspective and politics, the penicillin factory had become either proof that there were too many foreigners in the country or a symbol of the country’s failure to respond humanely to migrants. During the day, a fascist group called CasaPound marched outside protesting, while at night, health outreach vans run by aid groups provided medical services.

Across Italy, some 10,000 migrants and refugees are living in squats. In search of shelter, many have joined vulnerable Italians in occupying empty buildings. The housing crisis is not an accident. It is part of a deliberate strategy by the government to make Italy as inhospitable to migrants and refugees as possible.

On December 10, 2018, Matteo Salvini, the deputy prime minister and interior minister belonging to the far-right party the League, stood outside the factory as police entered and cleared it of residents. CasaPound, which had led a public campaign for the eviction, celebrated. But the paradox is that they themselves are squatters. CasaPound took over an empty office building in the center of Rome in 2003 and has housed people there ever since. This incongruence, between the penicillin factory eviction and inaction against CasaPound, is another example of how Italy’s far right is increasingly driving public opinion and policy on immigration. In late November, Salvini’s government passed a new law called the Security and Immigration Decree, but referred to by almost everyone in Italy as the “Salvini Decree.” It radically changed the Italian asylum system; eliminating the category of “humanitarian protection,” a form of protection given to people who are deemed to have “serious reasons” to flee their home country and cannot be deported. Since 2008, some 120,000 asylum-seekers in Italy have received this status.

Although immigrants comprise only 8 percent of Italy’s population, Salvini rails against “the invasion” and has blocked rescue ships from landing at Italian ports (“porti chiusi,” he likes to brag on Twitter and Instagram, meaning “harbors closed”). Despite the fact that, since 2014, the share of crimes committed by foreigners is decreasing within every single region in Italy, anti-immigrant sentiment, stoked by Salvini’s government, is at a dangerous, all-time high.

*

Italy’s current populist government came to power in March 2018. It is an unusual coalition between Salvini’s the League, which ran on a platform of “prima gli italiani,” or “Italians first,” and the anti-establishment Five Star Movement, led by Luigi Di Maio; the latter had never held national office.

The League, formerly the Northern League, used to call for the state of Padania to secede from Italy. A few years ago, it revamped itself as a nationalist party that was against immigration (during the election campaign, Salvini pledged to deport 500,000 migrants), the European Union, and austerity policies. The Five Star Movement, founded in 2009 by Italian comedian Beppe Grillo, also capitalized on growing discontent against traditional political parties with an eclectic platform of ideas pulled from across the political spectrum, such as advocating for a universal basic income and questioning Italy’s participation in the eurozone.

Before the election, the Five Star Movement said it would never form a coalition with the League because it was too far to the right. (Italy essentially has a proportional representation system, whereby parties need to form a coalition after the election if one party does not have a substantial majority of votes.) However, after an attempt to form a government with the center-left Democratic Party failed, the Five Star Movement proceeded to do exactly that. Although Five Star initially had more public support, with 32 percent of the vote compared to the League’s 17 percent, it has proved inept at governing, and over the past few months has lost many of its left-leaning voters. Meanwhile, the more experienced League has overtaken Five Star in popularity, as its base responds to Salvini’s anti-immigration stunts. By November 2018, support for his party had jumped to 34 percent.

Advertisement

The rise of the far right was not sudden in Italy, where the 2008 global financial crisis and subsequent economic slowdown was particularly severe. Under Silvio Berlusconi, the billionaire media tycoon who served as Italy’s prime minister four times, Italy borrowed large sums to stem the crisis’s effects; public debt leapt from an already sizable 103 percent of GDP in 2007 to nearly 127 percent by 2012. Proving inept at handling the crisis, Berlusconi was forced out in 2011—but not before he had paved the way for Salvini by forming coalitions with the League when he was in office and calling migrants a “time bomb.”

After Berlusconi, the government of Mario Monti, a former European commissioner, ushered in austerity measures such as cutting social spending and raising taxes. The effect on many Italian households was stark. The relative poverty rate crept upward, from 13.6 percent in 2008 to 15.8 percent in 2012, while household consumption plummeted to 1997 levels. As in much of Southern Europe, rising inequality and resentment of ongoing austerity measures—viewed by many as externally imposed by leaders in France and Germany—fueled populist sentiment and euroskepticism. The government failed to address growing resentment among the public.

Now Salvini has made attacking refugees and migrants a cornerstone of his politics (he also goes after feminists, gay people, journalists, and leftists, or “ticks,” the term used by Salvini). At the same time, Italy has seen a resurgence of support for fascism. Fascist ideology, always simmering on the margins of Italian politics, has acquired a growing respectability in political debates as a plausible alternative.

CasaPound, whose name references the pro-Mussolini American poet Ezra Pound, is a political party that calls its members “fascists of the third millennium.” It has proved adept at attracting young Italians, opening centers across Italy where young people can play sports, party (they throw raves), and hang out. The party claims poor and middle-class Italians have been left behind by a supposed preferential focus on migrants, provides social services in disadvantaged areas, and protests for housing rights. CasaPound’s supporters are predominately male and young. They are adamantly against a multiracial society and groups that advocate for human rights.

CasaPound does not have any representatives in parliament, and only holds local elected office in Ostia, a suburb of Rome. But its membership is expanding, and the group has a growing presence on college campuses. As of 2017, CasaPound had 20,000 members and 110 centers across the country, and many credit its media-savvy tactics with pushing the government farther to the right. Although Salvini has tried to distance himself from the group since ascending to power, he has a history with the organization. In 2014, the Northern League and CasaPound created a movement called Sovereignty to mobilize CasaPound’s supporters to vote for the League; there are pictures of Salvini dining with CasaPound leaders in 2015.

Casa Pound is one of several neo-fascist groups in Italy; others like Avanguardia Nazionale and Forza Nuova have been around longer. All of these groups have exploited the issue of migration to bolster their supporters.

From 2014 to 2017, some 624,747 people arrived in Italy on boats from North Africa, the majority crossing from Libya and coming from countries like Eritrea and Sudan, as well as, increasingly, West Africa. Under the previous center-left government, Italy poured money into the Libyan coast guard to block boats from crossing; in 2018, only 23,370 asylum-seekers arrived by sea. The drop is not because fewer people are leaving their countries, but because they are now increasingly intercepted en route by the Libyan coast guard, and then trapped in Libyan detention centers, where they are often tortured and sometimes sold to traffickers. Last year, at least 1,311 people drowned trying to reach Italian shores.

Salvini and his party stoke fears around migration by portraying migrants as criminals. Over the past ten years, overall crime has decreased in Italy by 8.3 percent, and crimes committed by foreigners have also fallen, with convictions at an all-time low. But each time a crime occurs in an immigrant neighborhood or when non-Italian citizens stand accused, Salvini exploits it. Such was the case with the brutal rape and murder of a sixteen-year-old girl, Desirée Mariottini, in a squat in San Lorenzo, an immigrant neighborhood in Rome. Two Senagalese men, one Nigerian man, and one Ghanaian man were arrested in connection with her assault and death. Salvini visited San Lorenzo and laid a rose at her memorial, then said he would come back with a bulldozer.

The Italian public grows ever more fearful. In a 2018 study, over half of Italians greatly overestimated how many migrants were in the country. Meanwhile, in the two months after Salvini became interior minister, Italian civil society groups recorded twelve shootings, two murders, and thirty-three physical assaults against immigrants.

Advertisement

*

There are roughly 100 squats in Rome spread across the city. These vacant hotels, offices, warehouses, and apartment buildings host an estimated 12,000 people. Many poor Italians lack stable accommodations; some 12,000 families are on the waitlist for public housing. Some of the squats are well organized by community or leftist political associations such as the Metropolitan Precarious Blocks, which also advocate for reform of housing laws.

One of the squats supported by Metropolitan Precarious Blocks is a former hotel in Tor Sapienza that currently houses some 500 people, including 150 children, many of whom attend local schools. Called “the four-star hotel,” its residents are from Africa, South America, and Eastern Europe; the majority have been living legally in Italy for years. Some found themselves homeless after the 2008 financial crisis, when many people lost their jobs and were unable to pay rent, resulting in evictions. The hotel was occupied in 2012; since then it has been carefully maintained by residents, and the rooms resemble mini-apartments.

When we visited, a recent kitchen fire in one of the rooms had cut the electricity supply, and people gathered in the lobby to connect their phones to portable chargers. Outside, kids rode their bicycles around the parking lot as dusk fell. Abay, thirty-two, has lived in the four star hotel with her family for six years. Abay is Ethiopian and her husband is Eritrean; they met in Khartoum, Sudan, and came to Italy together in 2008. Their children—Amen, six, and Kirubel, two—were born in Rome. Abay and her partner have political asylum, and while Abay works thirty-six hours a week as a hotel housekeeper making six euros an hour, she and her husband can’t scrape enough together for rent after the supermarket where her husband worked shut down. Without the squat, they would be homeless.

The government has indicated it wants to evict the building. Abay said she tries not to think about it, because she has no idea where they will go. The recent political changes in Italy scare her. “There are many episodes of racism every day. Every time I get on the bus, someone says something [to me]. They say, these are the people who live in that occupied four star hotel, they don’t pay the rent, they steal our jobs. It got worse since Salvini became interior minister.”

Despite CasaPound’s own illegal occupation of state property, the group has repeatedly protested immigrants’ habitation in other squats like the penicillin factory. “These people are the same ones who go to sell drugs on our streets,” they shouted outside the factory a few months ago. “We live in fear of crime and insecurity.” They chanted: “We defend our nation, we do not want immigration.” At the metro stop closest to the factory, Rebibbia, which is well-known as the site of one of Italy’s most notorious prisons, CasaPound flyers showed a bunch of white men waving the group’s flag with the headline “Vittoria!” CasaPound’s media representative declined a request for an interview.

In early January, journalists from the Italian newspaper Espresso reported that the headquarters of Avanguardia Nazionale had been in a building that belonged to Rome’s city council since 1991. Then, at a commemoration for several young people who died during a 1978 attack on far-right activists, two journalists from Espresso were violently assaulted by members of Nazionale and Forza Nuova just for showing up.

On our first day at the penicillin factory, the sky was gray and full of rain clouds. The first men we met were afraid that we were police. Other journalists had come recently with police escorts. Some men were chopping tree branches to use as fuel; others were filling jerry cans with water from a pump and taking cold bucket showers. Temperatures were in the low forties.

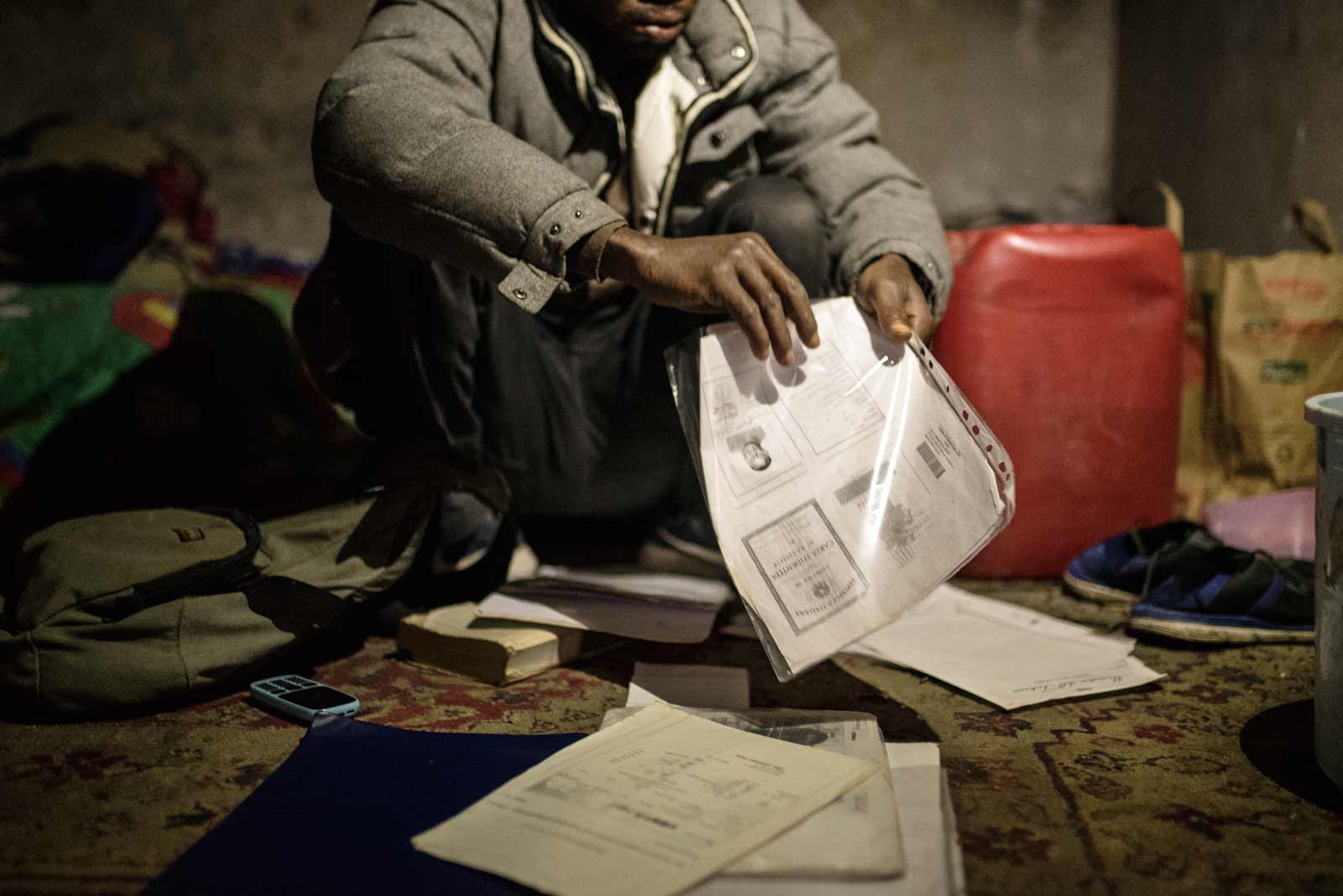

We met a young man, John, from Delta State, Nigeria. He was twenty-eight, and had been in Italy for four years. At the penicillin factory, he shared a small room with two other Nigerian men. The floor was made of green astroturf, and it was dark inside—there was no electricity. Rain leaked through the roof, a patchwork of cardboard and metal.

John had lived in a reception center in Sicily before making his way to Rome. He now had a residence permit, but couldn’t find work. John and his friends occasionally received a small amount of money from friends abroad. Otherwise, they begged on the streets.

A young woman, Felicia, came around the corner pushing a stroller with a small child. Twenty-seven, and originally from Lagos, Nigeria, Felicia has been in Italy for two years. She’d lived in the factory for over six months with her partner and two children until she found a shelter across town, for women and children only. “It’s very hard for him, and also hard for me, coming here so the kids can see their father,” said Felicia. She described the housing crisis across the city. “Some people are stranded; anywhere they [are when] night falls, they sleep there.”

The separation of families in state-funded shelters is another reason asylum-seekers turn to squats. Italy has a multi-tiered reception system that has struggled to provide adequate care and avoid corruption, including mafia-secured government contracts to manage reception centers for asylum-seekers and subsequent embezzlement of $41 million. The main system for integrating asylum-seekers—known as SPRAR (Protection System for Asylum Seekers and Refugees)—has been in place since 2002. SPRAR provided initial accommodation in a house, health care, and basic protection for those in need. It also saw the integration of asylum-seekers into local communities as critical to society’s well-being, and allocated funds for language classes, cultural activities, job placement and translators.

In late November, the “Salvini Decree” dismantled SPRAR. The program will now exist only for unaccompanied minors or people who have obtained refugee status, a process that can take years and only covers those who fled war or persecution. SPRAR will no longer provide asylum-seekers with housing in its facilities—instead they will be pushed into more temporary housing—or support to integrate into society. The Decree also eliminated “humanitarian protection,” a legal protocol that does not confer refugee status, but protects against deportation. It was granted to 25 percent of asylum-seekers in Italy who had fled their countries for “serious reasons of a humanitarian nature,” such as violence, famine or human trafficking. Because the status has to be renewed every two years, it is unclear what will happen to the more than 100,000 people who hold it. Losing the status means also losing a residency card and right to work; people who were in the country legally would suddenly become illegal.

“A person without a residence permit is a person banned from society,” said Salvatore Fachile, a lawyer with ASGI, a Turin-based national association of immigration lawyers.

The law also extends the period of time that the government is allowed to detain migrants and asylum-seekers from ninety days to six months and halts the asylum process for people deemed “socially dangerous.” New arrivals who request asylum will be processed in “hot spots,” which are essentially detention centers in the countryside where asylum decisions are made more quickly in order to then speed up potential deportations.

“These hot spots are a very dangerous thing, because it carries out the whole asylum procedure in a place far from the scrutiny of civil society, in isolation and in such a short time,” said Fachile. “This means that very few people will actually be able to exercise their rights [to asylum].”

The Salvini Decree claims it will make Italy more secure, but in practice, it all but guarantees there will be even more people living in the streets. Over the past week, authorities evicted some 300 migrants and asylum-seekers, including children, from a reception center outside Rome with only forty-eight hours’ notice. No one could tell the residents where the city would send them. Ahead of the eviction, some people started walking to Rome on foot.

*

Guglielmo Picchi is the League’s deputy minister for foreign affairs. His office is in the Palazzo della Farnesina, which houses the ministry. It is a large imposing building in the north of Rome, near the banks of the Tiber River. We met just a few days before the Salvini Decree became law.

“Our idea is pretty clear. We don’t want economic migrants,” said Picchi. “We don’t want illegal migration. Either you enter legally, or you don’t have any right to be here.”

The League is also working abroad to prevent people from leaving their countries in the first place. Picchi outlined for me how Italy was deploying a military mission to Niger, among other countries, to help police the border and prevent migration. Italy continues to support the Libyan coast guard with vessels, training, and spare parts to intercept ships at sea, despite that refugees and migrants are then returned to horrific detention centers.

Picchi did not foresee problems with the Decree’s implementation, which he said would help Italy process asylum requests more quickly and deport those who do not qualify. “We deem this bulletproof constitutionally speaking,” he said.

In recent weeks, more than a hundred cities and six regions in Italy have indicated they will oppose the Decree’s implementation, and some mayors have called it unconstitutional. “This (law) incites criminality, rather than fighting or preventing it,” said Palermo mayor Leoluca Orlando in early January. “It violates human rights. There are thousands, tens of thousands of people who legally reside here in Italy, who pay their taxes, who pay into pensions, and in a couple of weeks or months they will become… illegal.”

Meanwhile, the association of immigration lawyers is working with other advocates to file suit. “What we will do is go to the Constitutional Court and try to bring down this decree piece by piece,” vowed Fachile.

As more migrants have found themselves on the streets, grassroots efforts run by volunteers have tried to provide basic services. One is the Baobab Experience, which in 2016 erected a camp for people to sleep near Tiburtina train station on the east side of the city. Working with other groups, Baobab estimates that they have provided 70,000 people with some form of aid, including tents, meals, clothing, and legal assistance.

Three years ago, many African asylum-seekers and migrants stayed only briefly in Rome before catching trains or buses north, hoping to settle in countries like Germany and Sweden where there were more jobs. As a result, many passed through Baobab for only a few nights. But under EU policy, asylum-seekers can be returned to the place they first sought refuge. European borders have become much harder to cross now, as countries like Austria and Germany implement tighter controls to prevent migration. Most of Baobab’s residents are now stuck in Rome, and homeless.

Salvini has personally singled out Baobab for criticism, tweeting #Dalleparoleaifatti (in effect, “from words to facts,” implying that he’s delivering on his campaign promises) after Baobab’s camp was demolished by police this fall. The eviction displaced 200 people, at least sixty of whom then slept on the corner of a bus station behind Tiburtina. Another tactic of the government has been to harass and criminalize humanitarian workers. The Security Decree targets housing activists, increasing jail time for people who promote occupations of buildings.

Behind Tiburtina, men of all ages were unrolling sleeping bags and trying to stay warm. The train station, which is run by a private company, does not have public bathrooms, so people have to pay one euro every time they need to use a toilet, or go in the nearby woods. A group of young men from West Africa sat around an iPhone speaker blaring Sheck Wes’s “Mo Bamba.” Around 7 PM, several volunteers arrived with large plastic bins of pasta and paper bags filled with bread. After dinner, everyone stood around sipping tea and chatting about politics, and this seemed to be one of the most important things volunteers offered—a connection to Italian society.

The next morning, it was raining again. Everyone jammed their clothes in black garbage bags to keep dry. An Al-Jazeera TV news crew arrived, but most people did not want to be filmed. “Many journalists have come to photograph the evictions and conditions; nothing has changed,” said one man from Tunisia.

Temperatures in Rome in late December and early January hovered around freezing. In early January, the city council opened a room in Tiburtina station with thirty cots for migrants to sleep in. But the city did not let in some of the Baobab referrals, saying the spaces were for “vulnerable” migrants only. Because of this, twenty-four beds were left vacant.

To evict the penicillin factory’s occupants, police entered wearing blue helmets and riot gear. The factory residents did as they were told, gathered what belongings they could, and left. Some found other squats nearby, where they will live until they are forced out. But just last week, an Italian news agency reported that the factory had been re-occupied; an estimated forty men are living again among the ruins. The mayor of Rome, Virginia Raggi of the Five Star Movement, tweeted, “The ex-penicillin factory has been occupied again, this is unacceptable… After eviction there should be surveillance.”

On one of our last nights in Rome, we walked to the CasaPound building in the city center near the bustling Termini train station. It was raining again. We stood across from the entrance, marked by the group’s flag of a tortoise. Inside, the lights burned brightly. At the station, dozens of African men slept out in the open.

With additional reporting by Maurizio Martorana. Some names have been changed to protect privacy.