In Paris, in the late 1970s, the Hungarian émigré photographer André Kertész told me that he was the one who taught night photography to Brassaï (himself Hungarian-born), and it is true that Kertész had made such pictures in Budapest as early as 1914. But the student soon exceeded the master. Brassaï’s nocturnal photographs, collected in the seminal 1932 book Paris de nuit, with a text by Paul Morand, brought him considerable attention; Kertész instead roamed the Paris streets by day and also focused his energies on portraits of artists and writers like Marc Chagall, Alexander Calder, Colette, and Sergei Eisenstein.

Brassaï’s night photographs are only a small part of a 200-image retrospective that occupies an airy space in the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Peter Galassi, formerly the photography curator at New York’s MoMA, organized the show by category, descriptions Brassaï had himself created when systematizing his archive in 1947: “Paris at Night,” “Paris By Day,” “Pleasures,” “Graffiti,” “Body of a Woman,” “Places and Things.” The exhibition includes many vintage prints—the large formats were made before 1945, the smaller ones before 1968—and several photographs never seen before.

In a new edition of Paris de Nuit, published in 1976, Brassaï explained: “I was eager to penetrate this other world, this fringe world, the secret, sinister world of mobsters, outcasts, toughs, pimps, whores, addicts, inverts. Rightly or wrongly, I felt at the time that this underground world represented Paris at its least cosmopolitan, at its most alive, its most authentic.” His method was unconventional: “To gauge my shutter time, I would smoke cigarettes—a Gauloise for a certain light, a Boyard if it was darker.”

However nonchalant he wanted to appear, though, Brassaï in fact left little to improvisation during his nighttime outings. After pacifying curious policemen by showing them prints of his project, he would set up his tripod and pose his subjects meticulously: a circle of cesspool cleaners, a street walker, a group of thugs—his own wallet was lifted more than once. He used a burst of magnesium powder to create harsh lighting, giving an effect similar to that of the Expressionist films he saw in Berlin as a young man.

Because of the weight of the plates—a new plate had to be inserted in the camera for each exposure—he carried only twenty-four on each outing. He called them “little boxes of night.” He needed only two or three exposures to get what he wanted. Back at the studio, he would carefully print with ferrotyping, a tintype procedure that uses a direct positive on a thin sheet of metal coated with a dark lacquer or enamel to support the photographic emulsion; the process created a hard and glossy surface with sharp details.

Brassaï often cropped his images. He also did not hesitate to manipulate them if he thought it would make them stronger: for example, in a photo of two standing gang members, the face of the one on the right is cut in half by what seems like a section of wall but is, in fact, an opaque block Brassaï created in the darkroom. In 1935, Brassaï bought a Rolleiflex, a more portable, twin-lens reflex camera that enabled him to produce twelve negatives on each roll of film.

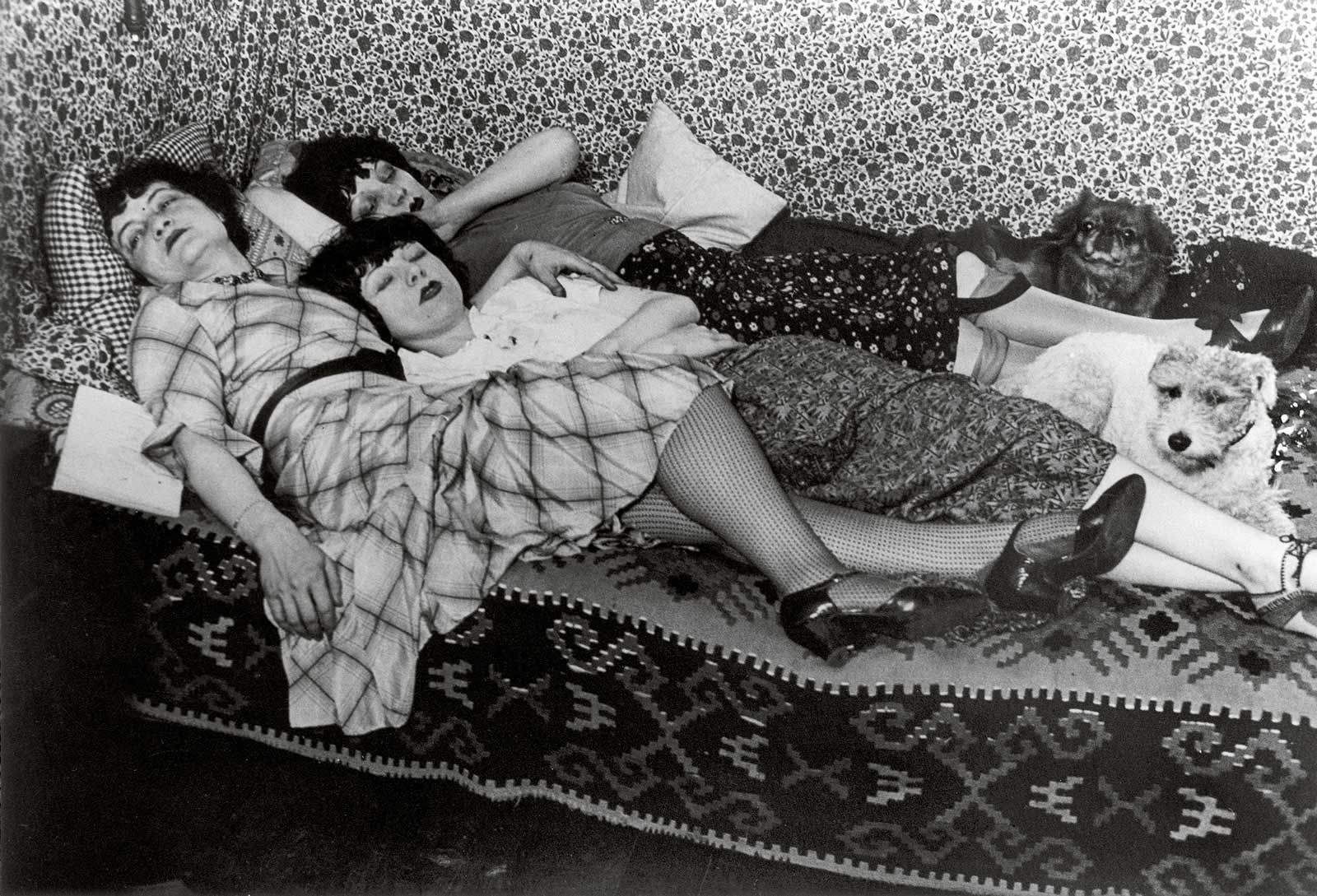

His outdoor portraits have a frozen quality, as if they were dramatic film stills in which the scene is immobilized. Among his images of Paris night life, of couples in bars or solitary figures on park benches—in one, lovers and a sleeping tramp share one bench—some were evidently staged, like those taken in a popular brothel, Chez Suzy, of a circle of prostitutes during what was known as the “presentation,” the moment when a client chose his partner; or that of a prostitute and her client in a hotel on the Rue Quincampoix, in which Brassaï’s assistant played the part of the client. Similarly, the young hoods of Big Albert’s gang, hanging out near the Place d’Italie, are clearly posed. In all of these, Brassaï was intent on creating a mise en scène to suggest a narrative.

Born in 1899 in Brassó (then part of Hungary, now part of modern-day Romania), Brassaï—who fashioned his name after his birthplace—had studied art in Budapest and Berlin, and had planned to be a painter or sculptor. When he moved to Paris from Hungary in 1924, he became a reporter to make ends meet, covering sports for a Hungarian newspaper and writing features for German magazines. At first, he commissioned photographs to illustrate the articles,but he later took up photography himself.

Brassaï’s love of art and literature (especially Goethe and Proust) shaped his vision. In addition to photographing, he painted, sculpted, and wrote—some of his books, on Henry Miller, on Proust, and especially his Conversations with Picasso, became classics. Brassaï managed to remember and vividly replicate Picasso’s tone and expressions. The poets Léon-Paul Fargue and Jacques Prévert served as his walking-tour guides through the city’s secret worlds.

In his portraits, Brassaï usually made no more than three exposures. The beautiful photograph of an old man carrying a lamb, taken in 1950 during mass in Les Baux-de-Provence, evokes a shepherd in a Christmas manger scene. Bijou, a street-walker and familiar Montmartre character, displays her stout figure and her jewelry-laden wrists, neck, and fingers, bearing a blasé, ironical expression. The market porter at Les Halles looks to one side, tightly crossing his meaty forearms over his chest as if to discourage an interloper’s approach. In Bal des Quatre Saisons’ (Lovers’ Quarrel), Brassaï uses a mirror to multiply the faces of disgruntled lovers or, in another, those of a happy group of drinkers, a technique he used in many of his photographs.

As well as his night subjects, Brassaï captured artists such as a young and cocky Dalí, a majestic Anaïs Nin, and a contemplative Henry Miller. Jean Genêt in shirtsleeves looks up with a mixture of shyness and defiance. Wearing a crumpled hat, the writer Fargue slouches on a bench, most probably during an evening adventure with the photographer. In another image, Pablo Picasso’s intensity is almost dwarfed by the shape of the gigantic studio’s wood stove towering over him like a Tatlin sculpture.

But Brassaï’s focus was not limited to people. His night images were often suffused with a fog, softening the magnesium flash. In a shot taken from Notre-Dame cathedral, a silhouetted gargoyle looms mysteriously high over the city lights and roofs. In many of his more atmospheric photographs, there is the sense of the graduated blending of a charcoal drawing, the erasure of limits. “Night does not show things,” Brassaï once said, “it suggests them. It disturbs and surprises us with its strangeness.” Though he knew the group and often published in the Surrealist magazine Minotaure, Brassaï resisted labels and did not want to be called a Surrealist: “I sought only to capture reality because nothing is more surreal than that.”

In a striking 1931 image of Parisian cobblestones (another version of the image appears in Paris de nuit) the darkened pavement gleams with rain. The image looks nocturnal but was in fact taken during the day. Brassaï’s fascination with texture is also visible in his shots of saltpeter-stained, fissured walls, such as those of the La Santé prison, the Hôtel de la Belle Etoile, or the concierge’s lodge, where mold and age create otherwordly lines. In another image, the spotted bark of a lone plane tree looks like an exotic snake.The buttress of the elevated metro casts a shadow resembling a man’s profile in a felt hat. These images of the mundane possess density, majesty, and evoke a sense of wonder—as if seen for the first time.

Along these lines, Brassaï’s magnificent “Graffiti” series was first published Minotaure in 1933, and exhibited at New York’s MoMA in 1956 in a show organized by Edward Steichen. The full series comprises more than 150 images, eleven of them currently at SFMOMA, including the famous The Sun King (circa 1945-1950), an Inca-like figure crowned with sun rays, the eyes deep circular holes. Rather than actual graffiti, they are figures carved into Paris walls and tunnels, in passages and under bridges. Brassaï’s lighting brings them into high relief. Their intensity brings to mind the painter Jean Dubuffet’s thick-textured portraits, and they often resemble cave art. Brassaï characterized their simplified lines as embodying “the birth of the face.”

Resident curator Clément Chéroux, with whom I toured the exhibition, explained that Brassaï alternated, sometimes during the same twenty-four-hour period, between photographing high life and night life. But while he excelled at depicting cheap dance halls and bars, Brassaï’s images of le beau monde, the high-society events to which an aristocrat girlfriend granted him access—500-place-setting dinners at the Automobile Club, balls at the Interallié, or Haute Couture soirées—are not as strong. Maybe because they were taken on assignment for magazines such as Harper’s Bazaar, they are competent but, undecided between flattery and irony, mostly unconvincing.

The section dedicated to Brassaï’s nudes also disappoints. Also originally published in Minotaure, they are flat, conventional exercises in geometry, strangely lacking in the sensuality that is otherwise abundant throughout the exhibition, as well as in Brassaï’s early drawings and woodblock work, or his small marble sculpture, Ariane (1971), ample as a prehistoric Venus.

After the war, Brassaï returned to drawing and published his work in a volume titled Trente dessins (Thirty drawings) accompanied by poetry by Jacques Prévert. He traveled the world on glamorous photo assignments, some in color, for Harper’s Bazaar and began exploring writing, filmmaking, and theater. He stopped taking photographs in 1962, the year his editor at Harper’s, Carmel Snow, passed away. He died in 1984, and is buried in the Cimetière Montparnasse, in the neighborhood where he did some of his best work.

*

In the late 1940s, Brassaï became a mentor to the American photographer Louis Stettner, whose work is also currently exhibited at SFMOMA in his first retrospective in the United States. Born in Brooklyn in 1922 to Austrian immigrant parents, Stettner spent much of his life zigzagging between New York and Paris, and was responsible for bringing to New York’s MoMA the 1951 exhibition “Five French Photographers,” featuring a whole generation of French humanist photographers: Brassaï, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Doisneau, Izis, and Willy Ronis. “Brassaï took me under his wing,” Stettner told a French journalist. “He was my teacher. I went to see him once a week to bring him my work, and in return he showed me his. Then we went out strolling in the streets of Paris.” Beyond bringing French photography to the American public, Stettner’s own work was distinctive for blending the social engagement of American street photography with the poetic sensibility of the French humanist tradition.

In 1935, when he was a teenager, Stettner’s parents gave him a Brownie box camera. “A sunny spring day after school, I was on the beach at Coney Island, looking up at the sky while walking,” Stettner wrote in his 1999 book Wisdom Cries Out In The Streets. “I found myself actually moving in space in complete harmony with the movement of the world. I felt a wonderful giddiness. For the first time in my life I was touching eternity, was pulsing along with the universe.” Fascinated, he started seeking that same sensation when taking pictures. He began going to the Metropolitan Museum Print Room: at the time, it was a place where any visitor could ask to view original prints by Atget, Ansel Adams, or Paul Strand. Then Stettner took a basic workshop with the left-leaning Photo League cooperative (he would later become a member).

He served during World War II, photographing for the US infantry, and went on a mission in Hiroshima three weeks after the atomic bomb “Little Boy” razed the city. Taking advantage of the G.I. Bill, he moved to Paris in 1947, and traveled throughout Europe on assignments. That Stettner did not get the reputation he deserves in the US is surely due in part to his strong leftist convictions (blacklisted as a Communist during the McCarthy era, he lost most of his assignments). And his relentless critiques of powerful curators like Edward Steichen and John Szarkowski, as well as of institutions such as New York’s MoMA (and museums in general) couldn’t have helped.

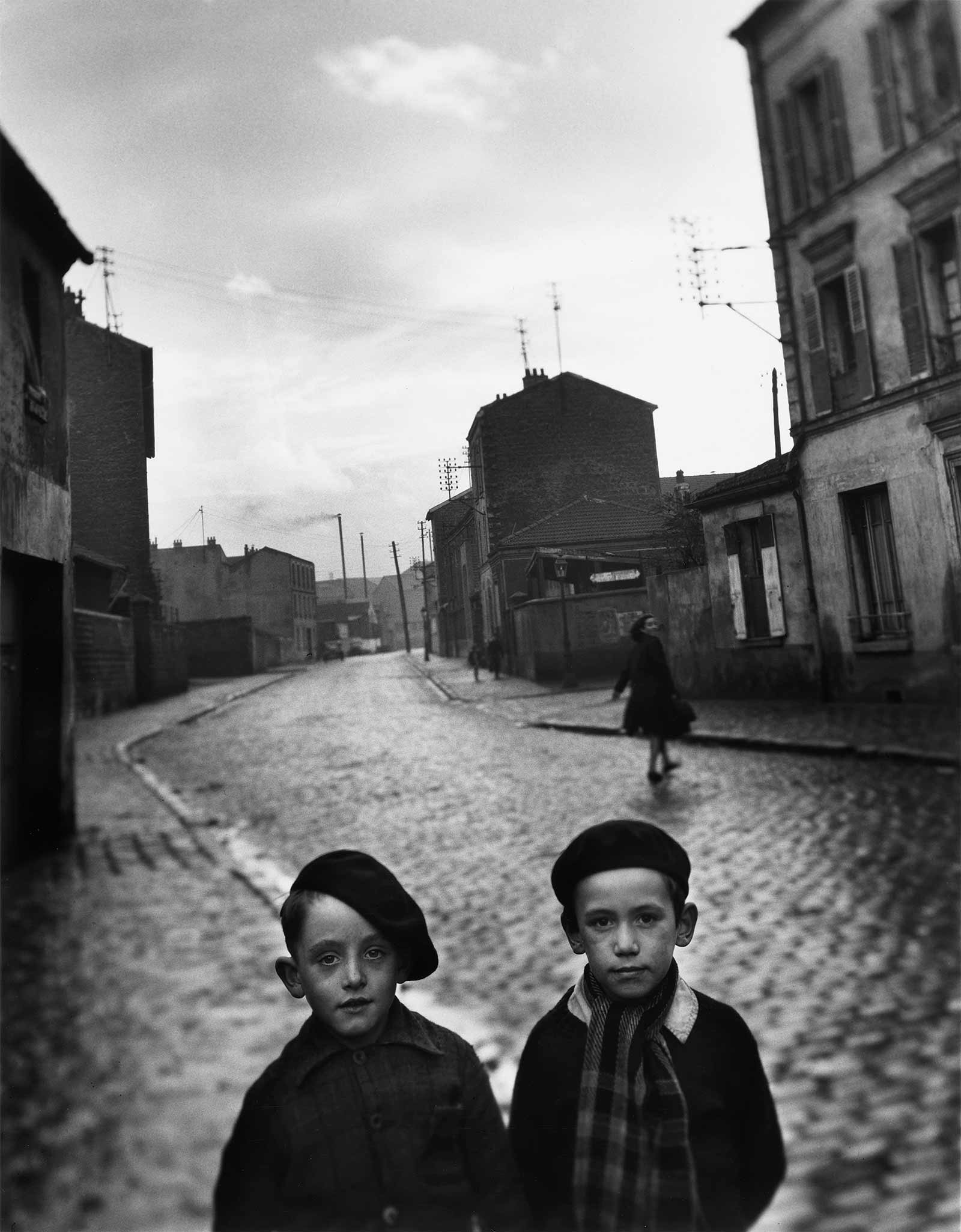

While exploring Stettner’s archive to prepare the show, Chéroux discovered a photograph showing Stettner’s mother holding two babies. He realized that Stettner was born an identical twin. The photographer, strangely, never spoke about his brother Irwin, a writer, who appeared in only one of his pictures, his naked feet sticking out of a bed and separated by the stem of a houseplant. Chéroux, however, found multiple instances of the theme of the double throughout Stettner’s work, from the two boys with matching berets in Aubervilliers (1947) to the two Dalmatians in a car seat in Spotted Dogs (1956). Mirror images, vitrines, shadows, and twinned street signs pursue the theme, as if the neglected twin were reappearing under other guises.

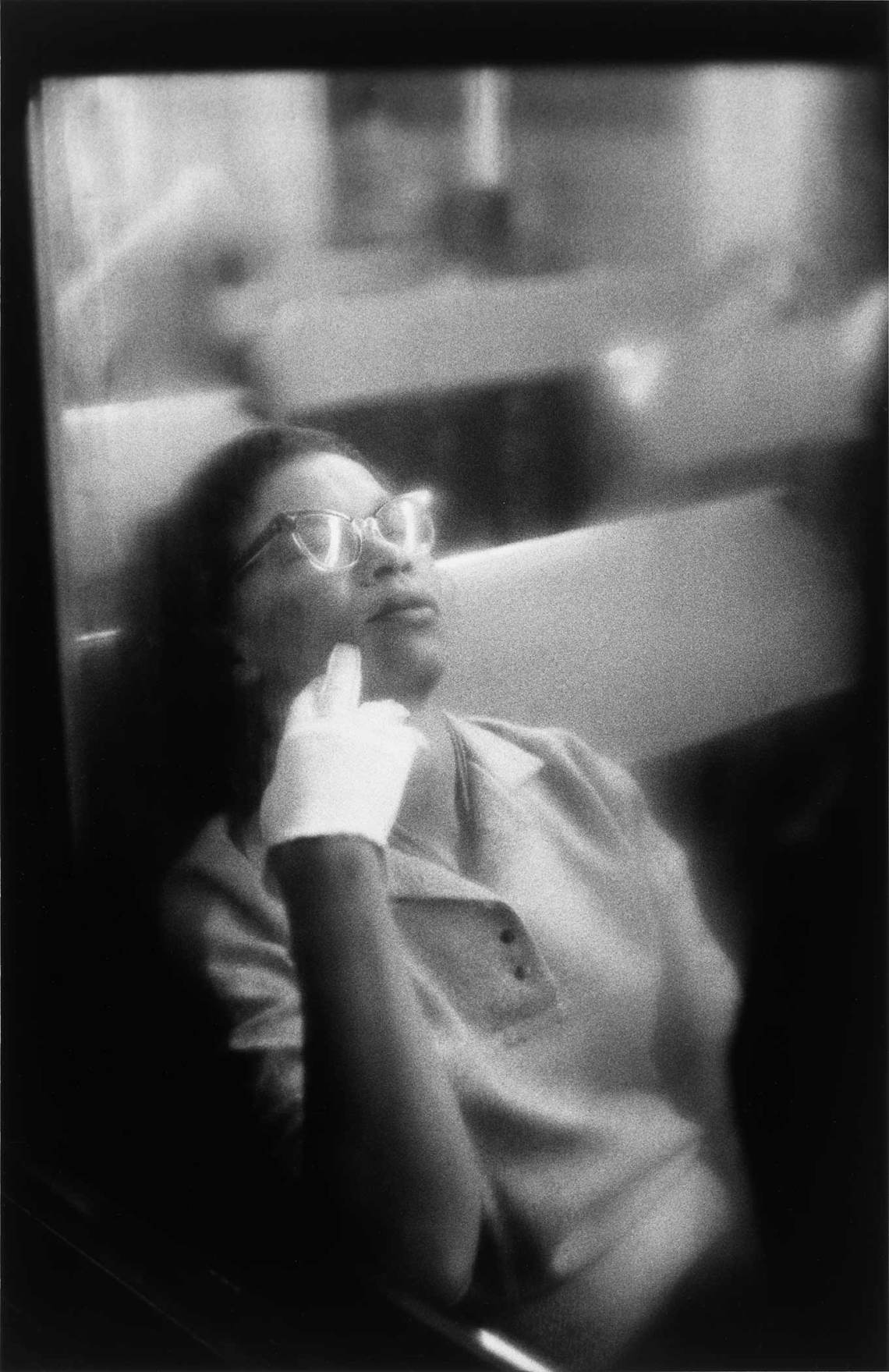

Like Saul Leiter, Stettner frequently photographed people through and around obstacles. In the case of his series of photos inside Penn Station, he shoots through the train windows, darkened with mist or soot. They act as frames within the frame as we peer into the train compartments where men and women sleep, play cards, chat, or read the papers in what feels like a secluded underwater world.

In his series of photos in the subway—made in 1946, several years after Walker Evans’s subway series (though Stettner did not know Evans’s work at the time)—Stettner used a square format and, contrary to Evans, did not hide his camera. He pretended to be fiddling with his camera, then photographed his subjects, some of whom were aware, others not, between stations, using long exposures. The subway provided him with endless sitters, offering Stettner the possibility of entering for a moment the lives of perfect strangers.

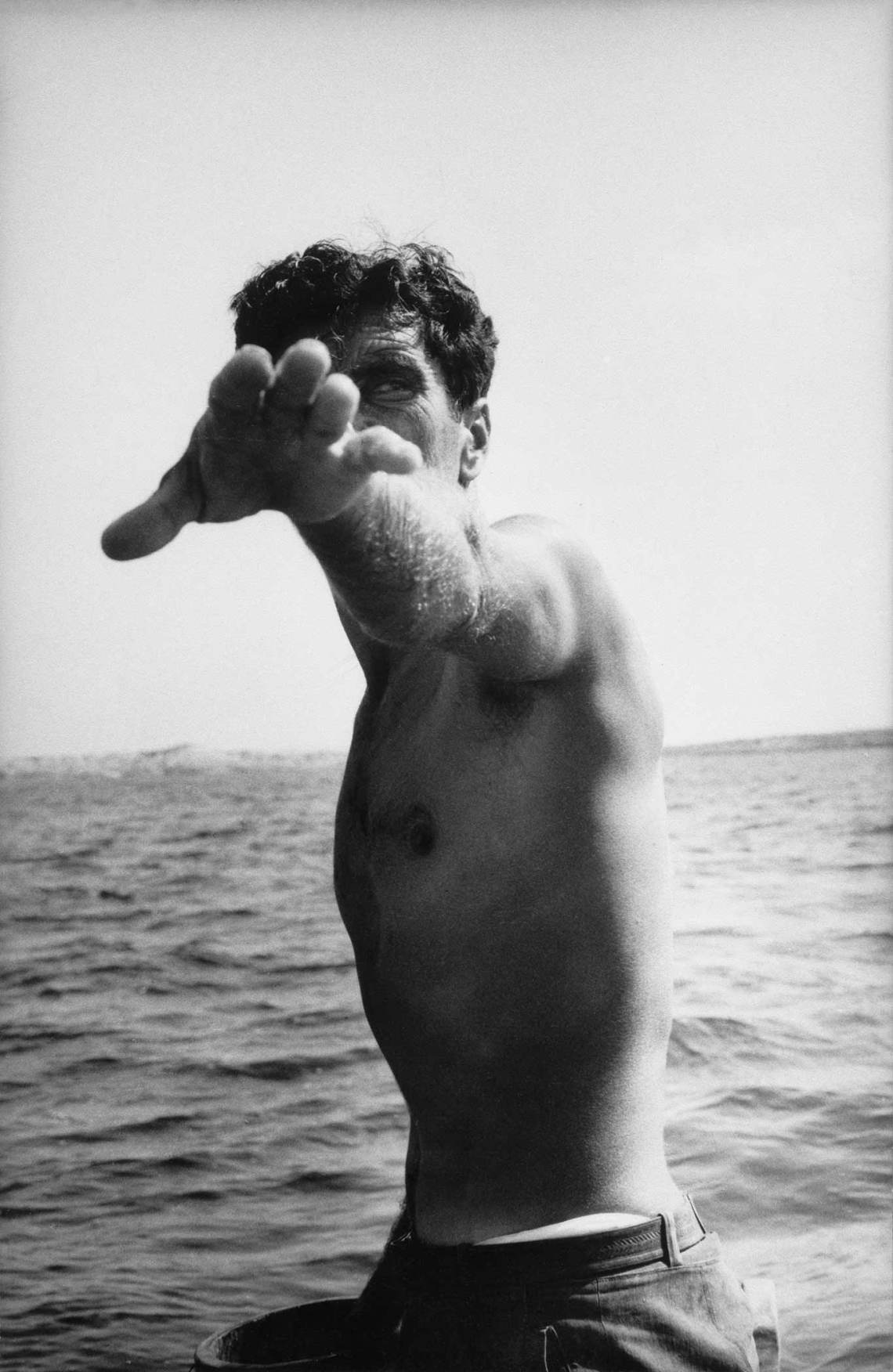

While living on the island of Ibiza, Spain, in 1956, Stettner photographed two fishermen, Pepe and Tony, at work. These photographs, part of a larger project, are taken at intimate close range—he was with them in their boat—and focused on their gestures. Still unpublished in full, the book on the two fishermen exists only in dummy form, its careful sequence demonstrating Stettner’s interest in the series more than the single image. Tony and Pepe are just two of the many workers that Stettner—perhaps inspired by the documentary photographers August Sander and Lewis Hine—photographed. There is pride in his subjects’ attitudes, but also seriousness and great weariness. No one smiles. In a video interview shown in the exhibition, Stettner describes spending time with a silent New Jersey garment worker before she finally said: “Nobody knows we exist.”

But Stettner also loved photographing the body in repose. Sleep figures prevalently in his work: sunbathers on the sand of Saint Raphaël beach in the French Midi, a sailor in a train station waiting room, and his famous image of a man spread-eagled on a bench on the Brooklyn Promenade like an upside-down angel in front of Manhattan’s skyscrapers. My favorite is a large, spare, almost abstract image of a man sleeping on a bench, taken in 2005 in New York, seen from above. His face is obscured, only his fragile neck and sparse hair are seen, with one hand hanging to the ground, the white mass of his shirt like a sail billowing in the night.

Stettner showed a compassionate tenderness toward his subjects, while Brassaï sought to create characters or archetypes out of the people he photographed. Like Brassaï, Stettner was a multi-talented artist, and during his very long career he practiced painting, sculpture, and collage as well as photography until late in life—he died in 2016. Both outsiders, they succeeded in discovering the secrets of their chosen city, Paris. And for both photographers, the street was their teacher.

“Brassai” is on view at SFMOMA through February 18 and will then be on view at the Palacio de Bellas Artes, Mexico, from March 14 through June 9. “Louis Stettner: Traveling Light” is on view at the SFMOMA through May 26.