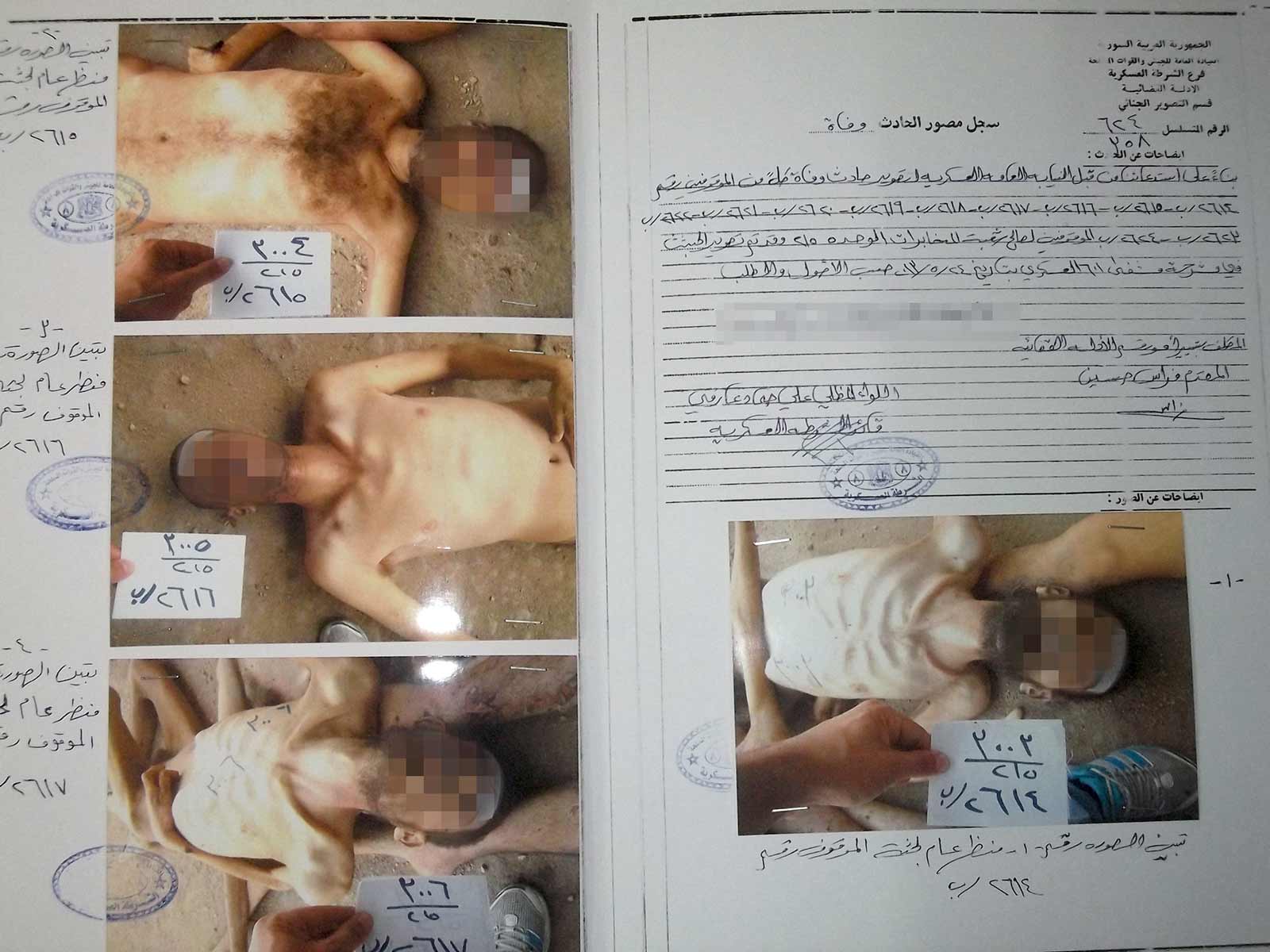

The following photographs contain disturbing content. They show people whom Human Rights Watch understands to have died in the custody of the Syrian government, either in detention facilities or after being transferred to a military hospital.

—The Editors

The war in Syria is an ongoing humanitarian catastrophe; it represents, too, the greatest political failure of the past decade—one that historians might well come to regard as the shame of our generation, for Westerners and Middle Easterners alike. Despite its savagery, the war has been extensively—though, critics say, ineffectively—documented in still photographs, videos, films, and on cellphones. This criticism rests on a misunderstanding of the relationship between photography and politics—a relationship that has been romanticized since Robert Capa and his comrades went to Spain, and that led to some of Susan Sontag’s sharpest insights in On Photography.

For eight years, the world has watched as the forces of a criminal butcher, President Bashar al-Assad, have bombed, raped, tortured, displaced, and murdered millions of their countrymen, women, and children. They have repeatedly used chemical weapons against civilians and created what Michael Young, a Lebanese journalist, has called “a humanitarian crisis of biblical proportions.” The country’s physical infrastructure—schools, hospitals, cities, towns, farms, marketplaces, water and electricity supplies—has been destroyed; so have its human relations and social fabric. An untold number of people, but probably more than 100,000, have been imprisoned in torture chambers. An even greater number have lost limbs, eyes, minds. The massacres that took place last year in Eastern Ghouta have been compared to those of Srebrenica during the Balkan Wars; “the violence is relentless and unbearably cruel,” a columnist for The Guardian wrote. A generation of children has been left traumatized, unschooled, orphaned; one trembles to think of the vengeance they will wreak.

The Syrian war has been called the death of liberal, or humanitarian, or democratic interventionism, the cause that Sontag and others vociferously championed in Bosnia; of international solidarity; of the responsibility to protect. The problem, though, is that Syria is not Bosnia (or the Spanish Civil War). The forces that Sontag lauded in Bosnia—the forces of democracy, secularism, religious tolerance, and multi-ethnic citizenship—are hard to find in the Syrian conflict. Tragically, the butcher is opposed by an equally heinous array of forces, including but not limited to al-Qaeda, al-Nusra, Ahrar al-Sham, and ISIS. Addressing this situation, Radwan Ziadeh, a prominent Syrian opposition activist, wrote, “Imagine how it feels to know your country is run by a terrorist regime and [by a] terrorist organization—the worst terrorist regime and the worst terrorist organization.” Damascus is not Sarajevo.

Of course, many Syrians do adhere to democratic values; they have bravely risked, and lost, their lives in pursuit of them. But values and a realizable political project are not the same; as Michael Ignatieff wrote in 2013 in The Boston Review, “The Syrian opposition has failed in making their cause a universal claim.” Richard Falk, a scholar of international law, has similarly noted, “Anti-Assad forces have been unable to generate any kind of leadership that is widely acknowledged either internally or externally; nor has the opposition been able to project a shared vision of a post-Assad Syria.”

The war in Syria has been much more dangerous to document visually than the one in Bosnia, since photojournalists (and journalists) in the former have been targeted, tortured, and murdered at unprecedented rates by all sides. Nonetheless, a wide array of photographs has been taken, and distributed, by everyone from amateur civilians under siege, using their cellphones, to professional Western and Arab photographers. In Regarding the Pain of Others, Sontag wrote that photographs of war “show how war evacuates, shatters, breaks apart, levels the built world.” This is certainly true of the Syrian photographs (see, for instance, the images that The Guardian ran in February of last year).

The traditional hope of photojournalists was that, in revealing the cruelty of war, the world would take what Martha Gellhorn had called “saving action.” But in this war, the perpetrators themselves—both in the Assad regime and in the terrorist groups opposing him—have photographed, indeed advertised, their own atrocities, of which they are apparently proud. So while documentation of war crimes is still vital, the classic function of photography is now sorely tested. Perpetrator photographs were made infamous by the Nazis and Khmer Rouge; in the early twenty-first century, they have made a startling resurgence. Much of what we know about ISIS’ atrocities comes from its own propaganda videos: images such as the beheadings of journalists and other hostages, and the burning alive of a Jordanian pilot, have been seared into memory.

Advertisement

The Assad regime, too, has created irrefutable evidence of its crimes, though these images may be less familiar. This is the subject of Operation Caesar: At the Heart of the Syrian Death Machine, by Garance Le Caisne, an independent French journalist who has been reporting in the Middle East for the past three decades. Originally published in France in 2015, the book has been translated into Dutch, Polish, Italian, German, Spanish, Finnish, and Romanian. In Germany, it won the prestigious Geschwister-Scholl Prize, which honors moral and intellectual courage. Here in New York, I have yet to meet anyone who has read it.

“Caesar” is the codename of a man who worked as a military-police photographer—that is, a government photographer—in Damascus. (Today, he lives under witness protection somewhere in Northern Europe.) Before the war, he photographed crime and accident scenes: car crashes, suicides, fires. But as anti-Assad protests erupted in the spring of 2011—peaceful protests, in which “Dignity!” was the first demand—Caesar’s work, and his life, changed. He was not particularly political, but “one day,” he told Le Caisne, “a colleague told me we were to photograph some civilian bodies.” Though described as terrorists, they were actually ordinary people from Deraa, where the first, peaceful protests spontaneously broke out after a group of schoolboys was arrested, and subsequently tortured beyond recognition, for the crime of writing anti-government graffiti. The bodies of the protesters that Caesar saw that day had been desecrated by soldiers, though the dead did have names. Soon, the corpses would be “just numbers.”

The protests continued; the bodies piled up; Caesar’s work became more gruesome. “I had never seen this before,” he recalled. “Before the Revolution, the regime would torture people to extract information. Now they were simply torturing people to death. I saw the candle burns… Some people had deep knife wounds, eyeballs ripped out, broken teeth, whip marks… There were bruises filled with pus… Sometimes, the bodies were covered in blood, and the blood was still fresh.” Each body was carefully photographed several times: one picture “of the face, one of the whole body, one from the side, one of the head and shoulders, one of the legs.” Every corpse was classified according to which arm of the intelligence services had jurisdiction over the victim in question. Medical examiners would issue a report for each body, typically ascribing the deaths to a “respiratory problem” or “cardiac arrest.”

The process was structured, scrupulous, precise, and hideous. “This time it is the state itself telling the story of the terror it is inflicting,” Le Caisne observes. “As opposed to the amateur films, full of emotion, that the activists for freedom shot in the streets of the cities, these official documents chill the blood.” In addition to physical agony, the photographs speak of psychic anguish, too. The victims, Caesar said, “knew they were going to die… They had their mouths open in pain, and you could sense the humiliation they had suffered.”

Caesar was aghast at the duties of his new job, and terrified, too. “I had to take breaks so that I wouldn’t start crying… I could picture my brothers and sisters as one of those corpses. It made me ill.” He decided to confide in his closest friend, Sami (another pseudonym)—a conversation, like many in Assad’s police state, that was fraught with danger even among trusted family members. Sami, who worked as a construction engineer in Damascus, had been awakened to the nature of the regime decades earlier, as a schoolboy, when a beloved elderly teacher was arrested, threatened with the rape of his wife, and “disappeared”: “I realized that we weren’t living in a country but in a vast prison,” Sami recalls.

Caesar wanted to quit his job and escape from Syria; Sami urged him to carry on. Working from Damascus for two years, the two friends downloaded 55,000 images of horror, transferred them to memory sticks, and smuggled some of them abroad for safekeeping over the Internet. Some of the photographs were already circulating clandestinely within Syria: “This macabre and secret databank allowed those who had received no word of a brother, a husband, a daughter to receive confirmation of their death,” Le Caisne writes.

A team of about a dozen photographers worked with Caesar. As they printed the photographs, “we couldn’t avert our gaze,” he says. “The detainee came back to life in front of us. We could really see the bodies, imagine the torture, feel the blows raining down. Then we had to write the report.” What does it mean—what toll does it take—to partake in such an enterprise? “We used to say, ‘On the Day of Judgement we will be asked to account for ourselves.’”

Advertisement

Through the testimony of various actors, including Caesar, Sami, doctors, and prisoners who survived, Le Caisne takes us inside the “machinery of death.” There is the transformation of hospitals into torture centers and the hasty sham trials that lead to inevitable guilty verdicts, imprisonment, and torture—and, often, execution. There is the widespread use of starvation within the prisons—due not to food shortages, but as a means of crushing the prisoners’ solidarity (“Hunger destroys all morality,” one observes). Most of all, there is the orgy of unrestrained torture. As one former prisoner puts it, Assad wants not only “to kill his people… by eliminating them physically, he wants to dehumanize them.”

Although I generally object to facile comparisons to the Holocaust, there is much in Le Caisne’s book that eerily echoes Primo Levi’s If This Is a Man, which charts what Levi called “the demolition of a man”—the project, that is, of annihilating people spiritually before their actual deaths. (The opening epigraph in Operation Caesar is from the writer Gustawa Jarecka, an inmate of the Warsaw Ghetto.) One Syrian shopkeeper, who spent six months in a detention center, recalls being taken into a room with mirrors. Le Caisne narrates: “‘Why are you looking at me?’ Abu al-Leith said tetchily. In the mirror he could see a man observing him. Disfigured face, emaciated body. Abu al-Leith was about to challenge him again when he realized the reflection was him. ‘I wasn’t a human being any more.’”

In 2013, as the situation became increasingly risky, anti-Assad activists smuggled Caesar and Sami—and their hard drive—out of the country. “Before the Revolution, we led a simple, modest life; we had no great ambitions,” Caesar recalled of himself and his family. “We had never visited the beautiful parts of Syria. We never had the time or the money. I had only been to the cinema twice in my life.” He never imagined that he would become an exile.

*

As with photographs of cruelty from the Nazi ghettos and concentration camps, and from the Khmer Rouge’s S-21 death camp, bewildering questions arise: Why were these photographs taken? Why would a state record its barbarism, even if its rulers never imagined that the photographs would be disseminated? Caesar himself wonders about this, and has no definitive answer. In part, the photographs may have been made because of the longstanding practices of the competing intelligence agencies within Syria, none of which trusts the others and each of which seeks to protect itself by documenting its activities. In addition, the photographs have reportedly been used by the intelligence services to inform families of the fate of their loved ones without having to produce an actual, mutilated body—and, perhaps, to warn relatives of their own possible fates. The photographs are also, I think, a sign of the Assad regime’s disconnection from the larger world, which—as with the Nazis and the Khmer Rouge—has led to a kind of moral dementia. Whatever the case, they clearly manifest the regime’s sense of impunity and its not-unearned confidence that it will emerge victorious from the war.

The deeper issue that the images call up is the persistence of “useless violence,” in Primo Levi’s words. This is violence that has no strategic or military purpose; it creates its own, enclosed world of pain, unanswerable to anyone or anything outside it. War and violence are not inherently irrational, Levi rightly noted: “Is there such a thing as useful violence? Unfortunately, yes.” Wars, he argued, “are detestable… but they cannot be called useless: they aim at a goal, although it may be wicked or perverse.” Useless violence, on the other hand, is a brutal tautology that exists outside of the rational, “an end in itself, with the sole purpose of inflicting pain.” During the Third Reich, Levi observed, “the best choice… was the one that entailed the greatest affliction… the greatest physical and moral suffering. The ‘enemy’ must not only die, he must die in torment.”

Jean Améry was another writer who, like Levi, belonged to a Resistance group and survived Auschwitz. After the war, Améry wrote of his torture at the hands of the Gestapo. In his view, torture’s temptation—if I can use that word—is, in part, its ability to endow the perpetrator with a sense of infinite power. Torture represents “the radical negation of the other,” Améry wrote. “[The torturer] wants to nullify this world, and by negating his fellow man… to realize his own total sovereignty… In this way, torture becomes the total inversion of the social world, in which we can live only if we grant our fellow man life, ease his suffering, bridle the desire of our ego to expand. But in the world of torture man exists only by ruining the other person who stands before him.”

*

In a 2015 interview with Foreign Affairs, Bashar al-Assad insisted that the Caesar photographs proved nothing: “Who took the pictures?… Who said this is done by the government, not by the rebels? Who said this is a Syrian victim, not someone else?” He later suggested that the photographs had been Photoshopped and dismissed them as “just propaganda.” Nonetheless, since reaching the West, the photographs have been verified by legal and forensic experts, including the FBI and war-crimes prosecutors. And they have been widely disseminated. Articles about them have appeared prominently in The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Guardian, and Le Monde. Human Rights Watch issued detailed reports and posted many of the pictures on its website, where they can still be found. The photographs have been displayed at the United States Holocaust Museum, the European Parliament, and the United Nations. Christiane Amanpour interviewed Caesar (concealed under a hood) on CNN; more crucially, he testified, in disguise, before the US Congress in the summer of 2014. (National Security Adviser Susan Rice and President Obama declined to meet with him; US Ambassador to the UN Samantha Power and Senator John McCain did.)

Earlier that year, in Paris, the world’s foreign-policy powerbrokers—including then-Secretary of State John Kerry and Laurent Fabius, France’s foreign minister—had viewed a presentation of the Caesar images. “The audience watched in silence, frozen in horror,” Le Caisne writes. “The ministers filed out without saying a word… John Kerry was ashen.” Later, a source close to Fabius described the photographs as “images we haven’t seen since the Jewish genocide and the crimes of the Khmer Rouge”; the collection of photographs “takes us back sixty years.” In short, these photographs have been seen by a lot of people, some of them important.

Caesar and his supporters, which included organizations like the exiled Syrian National Movement and Arab intellectuals such as Ziad Majed and Yassin al-Haj Saleh, naturally hoped that the photographs would have a catalytic effect on the Syrian war—or, rather, on Western attitudes and actions regarding it. “Assad’s Syria Recorded Its Own Atrocities. The World Can’t Ignore Them,” read a headline in The Guardian. Alas, a headline on the front page of The Times was more accurate: “Syrian’s Photos Spur Outrage, but Not Action.” Later, Le Caisne would say, “Caesar is disappointed by the international community’s inaction. He is wondering why he put his own life and those of his loved ones at risk and caused them so much fear.” Caesar thought, or at least hoped, that the photographs would lead to the toppling of Assad.

But the Caesar photographs—like countless others, including that of little Alan Kurdi lying face-down on a Turkish beach—didn’t do that because they couldn’t. Photographs cannot overthrow dictators; photographs can only bolster a political awareness that already exists, even if only among a minority. “Photographs cannot create a moral position, but they can reinforce one—and can help build a nascent one,” Sontag wrote in On Photography. “What determines the possibility of being affected morally by photographs is the existence of a relevant political consciousness.” The photographs from Spain taken by Robert Capa, Chim, and Gerda Taro spoke to a segment of the public, both here and abroad, that was already anti-fascist and strongly pro-intervention; it knew what the “saving action” was. The photographs from Vietnam taken by Don McCullin, Philip Jones Griffiths, and Larry Burrows circulated within a society deeply riven by debates over the war and by a highly visible, angry anti-war movement; the photographs from Bosnia taken by Ron Haviv, Gilles Peress, and James Nachtwey echoed the pro-intervention reports that journalists had been filing in major Western newspapers for several years.

When it comes to the Syrian war, a “relevant political consciousness” is precisely what does not exist.

*

The confusion over Syria—a confusion in which I include myself—is aptly illustrated by an anthology called The Syria Dilemma, edited by Nader Hashemi and Danny Postel. It was published in 2013, when the situation was not quite as dire and certain options remained, but the positions put forward by an array of Western and Middle Eastern intellectuals—and the intellectual disarray they manifest—still pertain. The essay titles provide a sense of the wildly disparate solutions offered by people who shared a loathing for Assad and who would, ordinarily, probably agree on many issues: “Syria is Not Iraq: Why the Legacy of the Iraq War Keeps Us from Doing the Right Thing in Syria”; “Supporting Unarmed Civil Insurrection”; “Against Arming the Rebels”; “Syria, Savagery, and Self-Determination: What the Anti-Interventionists are Missing”; “Syria: The Case for Staggered Decapitation.”

The specters that haunt this debate—sometimes acknowledged, sometimes evaded—are the continuing Iraq War, initiated by the US in 2003, along with the dismal failures of the later Arab Spring. Interventionists, who urge everything from no-fly zones and safe havens to military force, insist that “Syria is not Iraq.” This is, of course, true: no country is the same as any other; no conflict is like any other. “The Obama administration’s inability or unwillingness to act may be remembered as one of the great strategic and moral blunders of recent decades,” Shadi Hamid of the Brookings Institute wrote. “Hoping to atone for our sins in Iraq, we have overlearned the lessons of the last war.” Afra Jalabi, a Syrian writer who lives in Montreal, reports: “Activists get frustrated when Syria is compared to Iraq. ‘They say Iraq was an egg that was crushed, but Syria is a chick trying to break its shell from within and is in need of protection.’”

Certainly, lazy conflations should be avoided—as evidenced by those who equated the United States’ bombing of Milosevic with the United States’s bombing of Hanoi. The problem is that, though different from Iraq, Syria resembles it far too much—and resembles Bosnia, or even Tunisia, far too little. Like Saddam’s Iraq, Assad’s Syria was a sectarian, only nominally secular state run by a corrupt, Mafia-type family and its henchmen who controlled the country’s wealth, ruled through a totalitarian Baath Party, practiced decades of state terrorism against its citizens, and created a vast network of intelligence services and informers. After Saddam’s Iraq, Syria was regarded as the worst regime in the Middle East: another “republic of fear.” Independent civil society was aborted and, as a former prisoner tells Le Caisne, “At school, books and the Baath Party inculcated bitterness, a hatred for democracy.”

To say that Syrians had little chance of creating a multi-confessional, tolerant democracy is not, as some have implied, a form of Orientalist superiority. It is, rather, a sober recognition of the fact that years of violent repression result in deeply damaged societies that generate deeply damaged human beings for whom political or sectarian vengeance is often the political program of choice.

This doesn’t mean that President Obama’s essential passivity was the only choice. Early in the war, Obama had several options, all bad; it is hard, indeed impossible, to know whether he chose the least-bad, medium-bad, or most-bad. What is clear, however, is that his non-actions were a gift to Russia, Iran, and Hezbollah, which have fought this war with all the passionate intensity that the West has lacked.

*

Should the Caesar photographs be shown? They are, after all, unbearable. At a conference in Stockholm last year, I screened some of them. During a break in the proceedings, a young woman approached me. She had been born in Sweden, but her parents were political refugees from Eritrea. She told me, with a smile and without anger, that presenting these photographs was an affront to those depicted in them. She asked if I would show the pictures if relatives of the prisoners were in the audience; while I acknowledged that this would cause great pain, I said I would. She accused me of exploiting and oppressing Syrians; I said it was Assad who had done that.

In the question-and-answer session that followed, this issue arose again. Finally, a man who identified himself as a Syrian poet—he had gone into exile years before 2011—rose and spoke with passion. He said that people all over Syria were scrutinizing these photographs for news, however horrible, of their loved ones. And he urged people in the West not to turn away from Syrians’ agony—whether on the pretext of fatigue, helplessness, confusion, respect, or anything else.

The photographs have certainly not accomplished what Caesar and others hoped. But then again, atrocity photographs from the Nazi campaigns—which reached the West from the early days of World War II—did not persuade the US to enter the fray; a Japanese attack did that. And though Caesar’s images have not resulted in immediate action, they will almost certainly be used in war-crimes trials if Assad and his cronies are ever overthrown. In addition to Caesar’s evidence, more than 600,000 written documents that directly link Assad and other officials to the torture practices have been smuggled out of Syria; The New Yorker has described them as “a record of state-sponsored torture that is almost unimaginable in its scope and its cruelty.”

The Caesar photographs force us, as Hannah Arendt wrote in 1944, “to account for the things which men do to men.” Arendt believed that this accounting was the responsibility of every human being; I do, too. This is not enough, certainly. But it is impossible to imagine any form of solidarity, or of sane political action, without it. And it is important to remember that the Caesar photographs didn’t fail us; it is we who failed them.

*

This past December, The Washington Post published a long, extensively documented article reporting that Assad’s torture prisons are being emptied out. This should have been good news, but as so often in the Syrian war, it was not. The “dwindled” number of prisoners, the Post reporters explained, is due to an increase in executions. The paper added: “The Syrian government did not respond to requests for comment for this article.”

Operation Caesar: At the Heart of the Syrian Death Machine, by Garance Le Caisne, translated by David Watson, is published by Polity.