Human skulls are enduring motifs in art history, and Jasper Johns has a longstanding acquaintance with them. A skull peers out from the corner of his work as early as 1963–1964, in a bright, blocky painting called Arrive/Depart. The title alone offers a view of life as starkly unsentimental as any memento mori. We arrive in the world, we depart from the world, and there is no guarantee of happiness in between.

The theme permeates Johns’s large, very moving show at the Matthew Marks Gallery in Chelsea. Johns, who is now eighty-eight years old, did much of the work in the past few years, and it captures him meditating on age and evanescence with remarkable directness. You would have to turn to Edgar Allan Poe to find an American artist more in touch with the grave. Yet the show doesn’t feel lugubrious, perhaps because Johns has been prolific and inhabits the new work so vividly.

The works on view are crisply divided into five series, the largest and most ambitious of which might be called “Farley Breaks Down”—to borrow a phrase that is stenciled across two paintings in a way that suggests that the letters of the alphabet are themselves breaking down or decomposing as they fade in and out of view.

Farley, as it turns out, is James C. Farley, a former marine who served in Vietnam and survived the war. The dozen works in the show that overtly reference him are based on a 1965 black-and-white photograph in Life magazine by Larry Burrows, the British photojournalist. It shows Farley weeping in a supply shack; he had just completed a helicopter mission that left one of his buddies dead. He later said in an interview that he felt a twinge of embarrassment when he first saw the photograph in Life. Real marines are not supposed to cry. Yet the image is stirring precisely because it undercuts clichés about American heroism. Farley is a masculine version of the “Mater Dolorosa,” the art-historical archetype of the weeping woman.

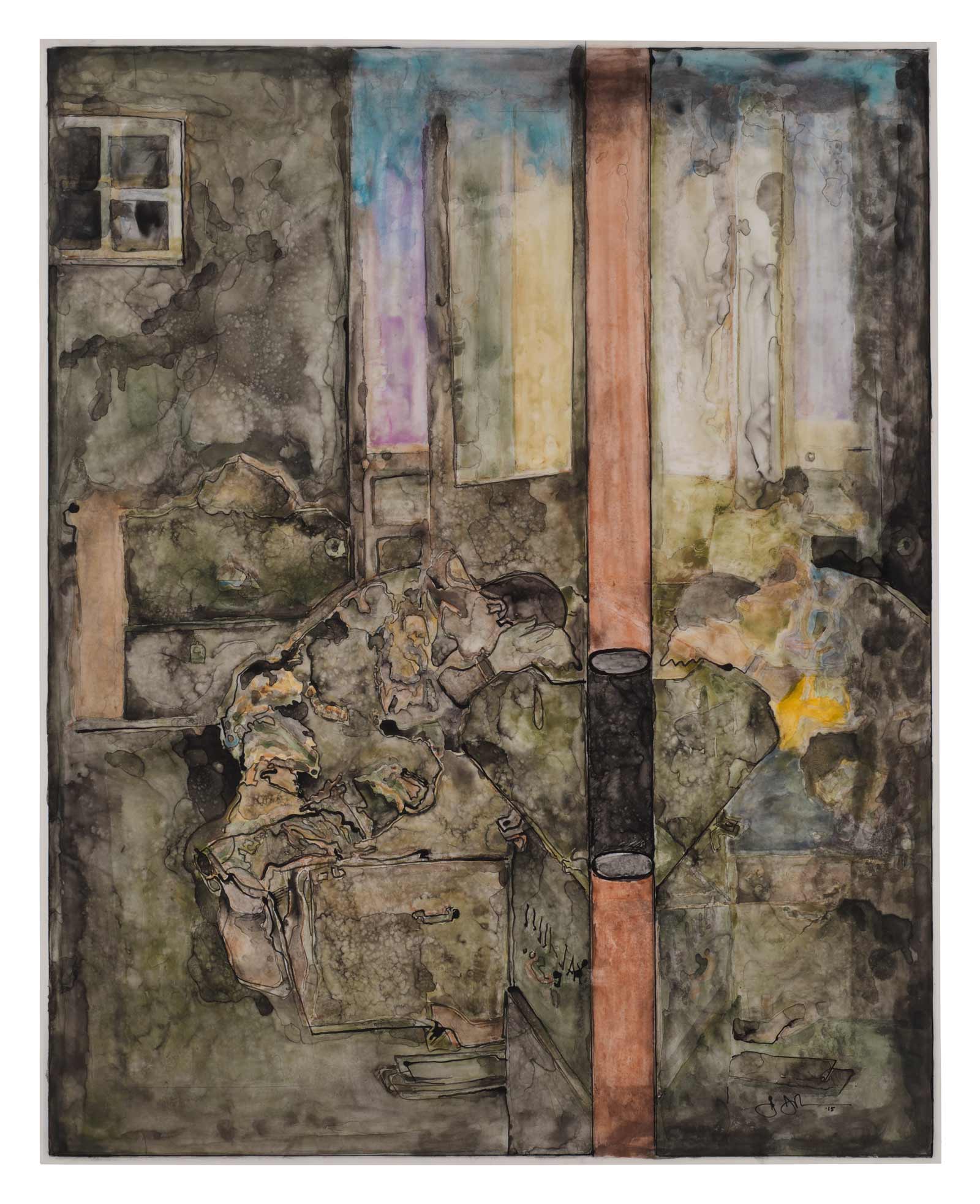

In Johns’s many depictions of him, Farley is usually paired with a second figure—a mirror-image, Farley in reverse. The two figures never touch or mingle; a beam stands between them with the insistent verticality of a Barnett Newman “zip.” But look closely and you will see what appears to be a heart shape, or rather the matching halves of a heart, rising out of the seam that separates Farley from his doppelgänger. The distance between them is momentarily bridged.

It’s fascinating that Johns, who earned his first fame with paintings of targets and the American flag, has returned, after a celebrated career spanning more than six decades, to military imagery. Johns himself served in the army during the Korean War. This is not to say that his paintings are autobiographical in the conventional sense, nor that they can be read primarily as anti-war statements. Rather, the public references in his work transform themselves into a private symbolism with which Johns takes possession of his interior combat.

Johns, who grew up in small-town South Carolina in the years following the Depression, seldom offers explanations of his work. For most of his adulthood, he has lived alone, and the symbolism embedded in his paintings adds a protective distance between him and his audience. Tellingly, perhaps, all but six of the works in the current show are untitled.

He can be more playful than is sometimes acknowledged, and the new work abounds with perceptual riddles. Attentive to the dead space between objects, Johns often creates volumes from voids. In the current show, especially in the works that belong to his Regrets series, hidden forms popped out at me: an urn, a tombstone, a skull in chic sunglasses, and, of all things, a seated old woman with a ruffled bonnet resembling Whistler’s mother.

The work can also be enjoyed in purely formal terms. This is especially true of a group of drawings done in ink on sheets of plastic, an idiosyncratic medium from which Johns extracts a tender, tremulous draftsmanship. Plastic, unlike paper, has no absorptive fiber, causing ink to pool on the surface or leave runny rivulets. Some of Johns’s drawings in this medium evoke other kinds of spillage—spilled milk, spilled seed, spilled tears.

The show also inspires color-stained thoughts. There was a period, earlier in his career, when Johns downplayed his gifts as a colorist, to the point where his close friends noticed the absence. In an interview with Joan Retallack in 1991, the composer John Cage mentioned that the artist Robert Rauschenberg, a former lover of Johns’s, “used to say about Jap that he was the only artist he knew of who was color-blind, who didn’t know the difference between two colors… he didn’t respond to color.”

Advertisement

Today, that claim is in need of revision. Of the two untitled paintings devoted to the Farley theme, the larger one stands about six feet tall and offers an exquisite symphony of greens. They range from the palest white-infused viridians to yellowish chartreuses to hues that look so mossy and alive you would think they could grow another coat of paint on their own. When you step back and contemplate the painting from across the room, you might think you are seeing an aerial view of farmland divided into so many pristine garden plots.

The color green, oddly or not, occupies a singular prominence in Johns’s biography. It was an all-green painting of his that initially caught the eye of art dealer Leo Castelli. In March 1957, Castelli happened upon Johns’s Green Target in a group show at the Jewish Museum and wondered who the artist was. Less than a year later, Castelli gave Johns his debut show. Today it is treated in textbooks as an overnight sensation that halted the reign of Abstract Expressionism, with its quest for lofty truths, and inaugurated a new kind of art that lavished attention on everyday objects and images.

I once asked Johns what led him to paint his Green Target that color. He replied, “It’s probably green because I was so accustomed to using primary colors. I was trying to do something else.” By something else, I presumed he meant secondary colors. The comment was eye-opening. In his early work, his choice of colors, as much as the targets and flags he adopted as his subject matter, was governed by a self-imposed system that minimized the exercise of personal taste. These days, at last, he is free of such constraints.

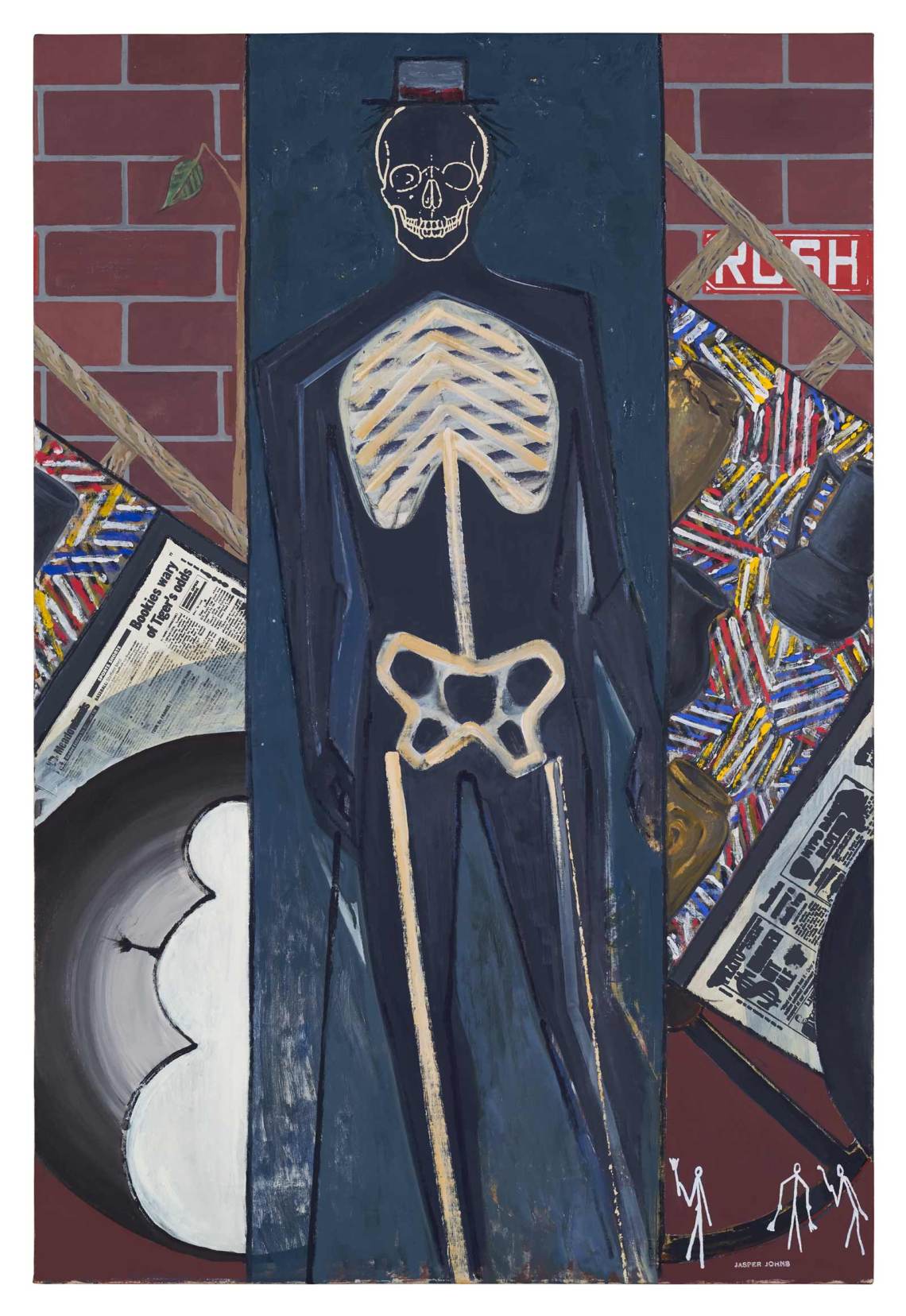

The emotional climax of the Matthew Marks show comes in the back gallery, in a room of skeletons that reverberates with the memory of distant masters: Van Gogh, Cezanne, Picasso, who each painted potent likenesses of skulls. Johns’s new skeleton motif, I was told, derives from a dollar-store toy, a foam puzzle that was given to him by a friend. His riffs on the image are impressively varied. The skeletons slip out of one work and into the next in a mesmerizing procession that can put you in mind of the imagery of Mexico’s Day of the Dead.

In a breathtaking suite of twenty-four drawings, roughly book-sized, the skeleton metamorphoses from a figure of meticulously embroidered detail into a mere blur of ink. In one particularly enchanting drawing, the skeleton is a swatch of pearl gray, outlined in white and floating against a darker, gunmetal-gray ground. His facial features have been rubbed away, but he has a muffled sweetness about him, perhaps because the string in his hands, a reference to the sweeping curves in Johns’s Catenary series (and his show at Matthew Marks in 2005) is here reinvented as a jump rope.

Elsewhere, in a vibrant oil-on-canvas painting standing more than four feet high, the skeleton is encased in a rectangle of Prussian blue that thins out toward the bottom. The space can be read as a coffin or a crypt, and its occupant is buoyantly rendered in broad ivory strokes. His rib cage is especially dramatic; it looks like an upside-down palm leaf, or perhaps a shovel. I loved the “rush” sign affixed to the wall in the background, a red rectangle lifted from the workaday realm of packing and shipping. It is rendered in urgent upper-case type, a reminder that time is “rushing on” despite our wish to stick around for another leisurely cup of tea.

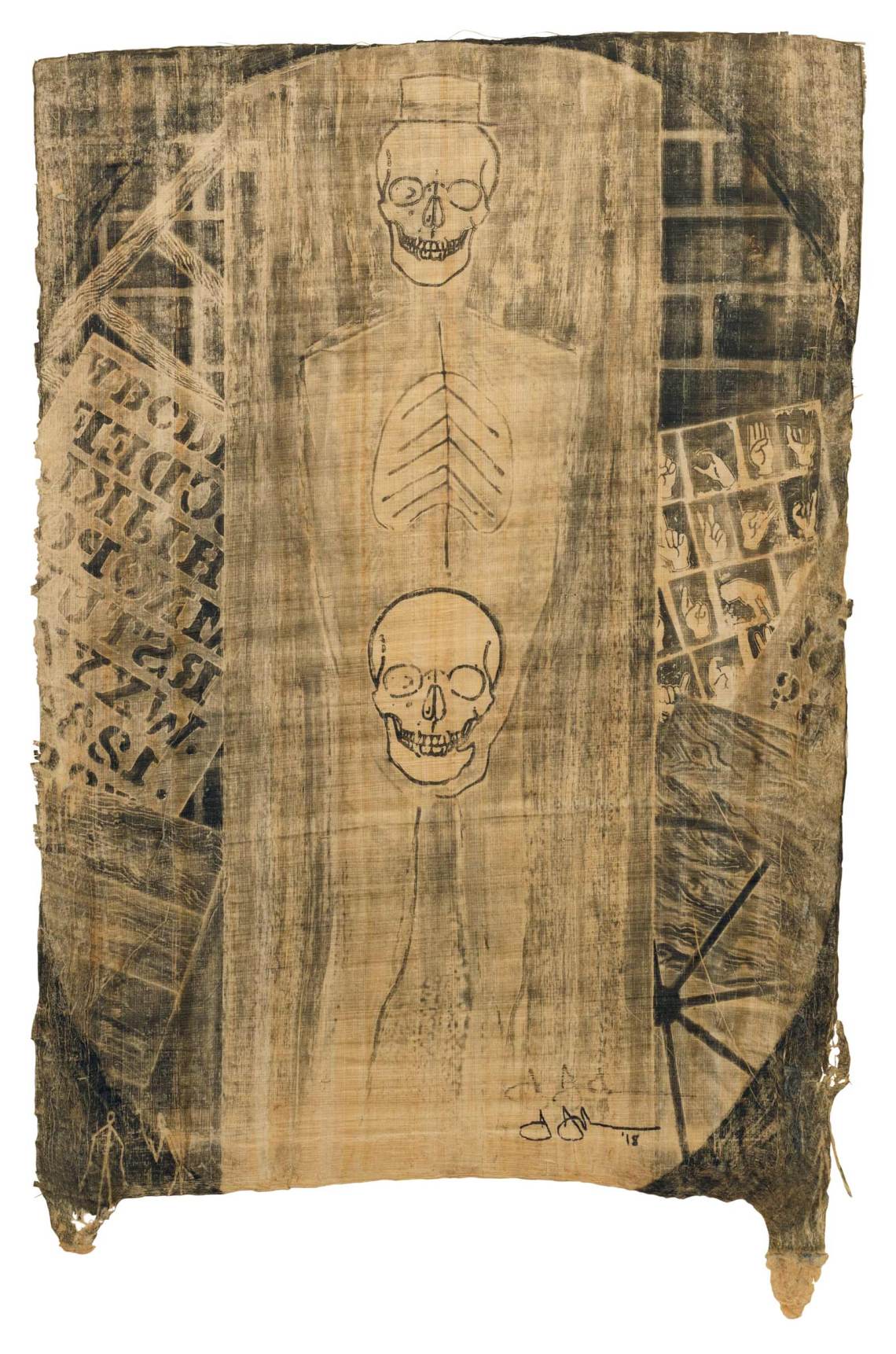

In yet another variation, an etching printed on a sheet of Egyptian papyrus, the skeleton appears in a Cubist parlor. With its oval composition and sepia tones, the etching evokes the early efforts of Picasso and Braque and the advent of analytic Cubism, a brave-new-world “ism” that here seems quaintly antique. Hints of non-art languages flank the skeleton on either side. There’s a left hand gesturing in sign language, a stencil with the letters of the alphabet (in reverse), and a group of stranded stick figures who appear to be trying to SOS for help. So many languages, so little communication.

Advertisement

Johns has been borrowing images since the beginning of his career. He has been hugely influential on succeeding generations of artists who cull their motifs from the ever-widening image bank of popular culture. But unlike many of those who followed him, Johns’s recycled imagery isn’t intended ironically. He’s not seeking—by recycling a dollar-store skeleton or a picture from Life of a crying soldier he never met—to make a droll comment about the death of originality, or an appraisal of an era in which media images have supplanted reality.

Rather, it seems, Johns’s surrogates and stand-ins allow him to voice feelings that could not otherwise be expressed. The anguish of the mute body has been one of his longtime, if underacknowledged themes. It’s suggested even in his early masterwork Target with Plaster Casts (1955), which contrasts a target-circle, a dream of wholeness and emotional contentment, with a body that cannot express itself—the parts cut up and tucked away into boxes. Some critics see a night-and-day difference between Johns’s early and later work, arguing that he now pursues emotion as zealously as he once renounced it. But to me the works are all of a piece. There’s a direct line connecting the Green Target to the tears of Farley and even to the jump-roping skeleton. They hint at things that are felt but which remain unsaid and unsayable.

“Jasper Johns: Recent Paintings & Works on Paper,” is on view at Matthew Marks Gallery through April 6.