On the last day of 1980, the announcement came: our Pioneers’ Palace had been invited to perform at the Exhibition of Achievements of the National Economy in Moscow. Not right away, but in July, and not the entire Palace, with its 264 after-school circles delivering well-rounded education to some 4,000 kids of our southern Russian town, but dancers and singers only. That ruled me out: during the second-grade ballet auditions, I had learned, terminally, that mine was no body for ballet and had transferred to the drama circle. But the vocal-dance collective known as “Pioneers of Kuban”—Kuban being the name of our region—needed an announcer for the Moscow show. My mother, who’d made it her life’s quest to raise me in such a way that I would never regret not having a father, decided it should be me.

Pioneers’ Palaces existed in every regional center of the USSR and had nothing to do with Lewis and Clark and everything to do with Vladimir Lenin. At the end of the third grade, all Soviet schoolchildren took a pledge of allegiance, promising to defend the Motherland and live, study, and fight as the great Lenin bade us. “Be ready! Always ready!” A scarlet neckerchief ironed religiously every morning guaranteed free admission to the Pioneers’ Palaces, where qualified specialists fashioned us into future chess prodigies, folk singers, classical pianists, dancers, artists, sculptors, engineers, journalists—any field of accomplishment your heart desired. My heart desired ballet: with its tall windows and even taller ceilings, the ballet studio was the best place in the entire Palace. But the ballet troupe had strict body aesthetic criteria. The drama circle, on the other hand, admitted everyone.

A gymnasium before the Revolution, and before that, a mansion, the Palace occupied an entire block in the Red Army Street, in the center of town, its decorative frontal arches and grand foyer a departure from the one-storied “private-sector” houses and Khrushchev-era apartment buildings, the two dominant architectural trends in our provincial town. A marble staircase with filigree railings led to the second floor. On the first landing, a large stained-glass window with revolutionary symbols lent a colorful backdrop to an alabaster statue of Lenin. On sunny days, rays filtering through the stars and bugles created a halo around the leader of the world proletariat, transforming the staircase into the proverbial bridge to the bright tomorrow, an effect furthered by the sound of drums and trumpets coming from the downstairs orchestra rehearsal rooms.

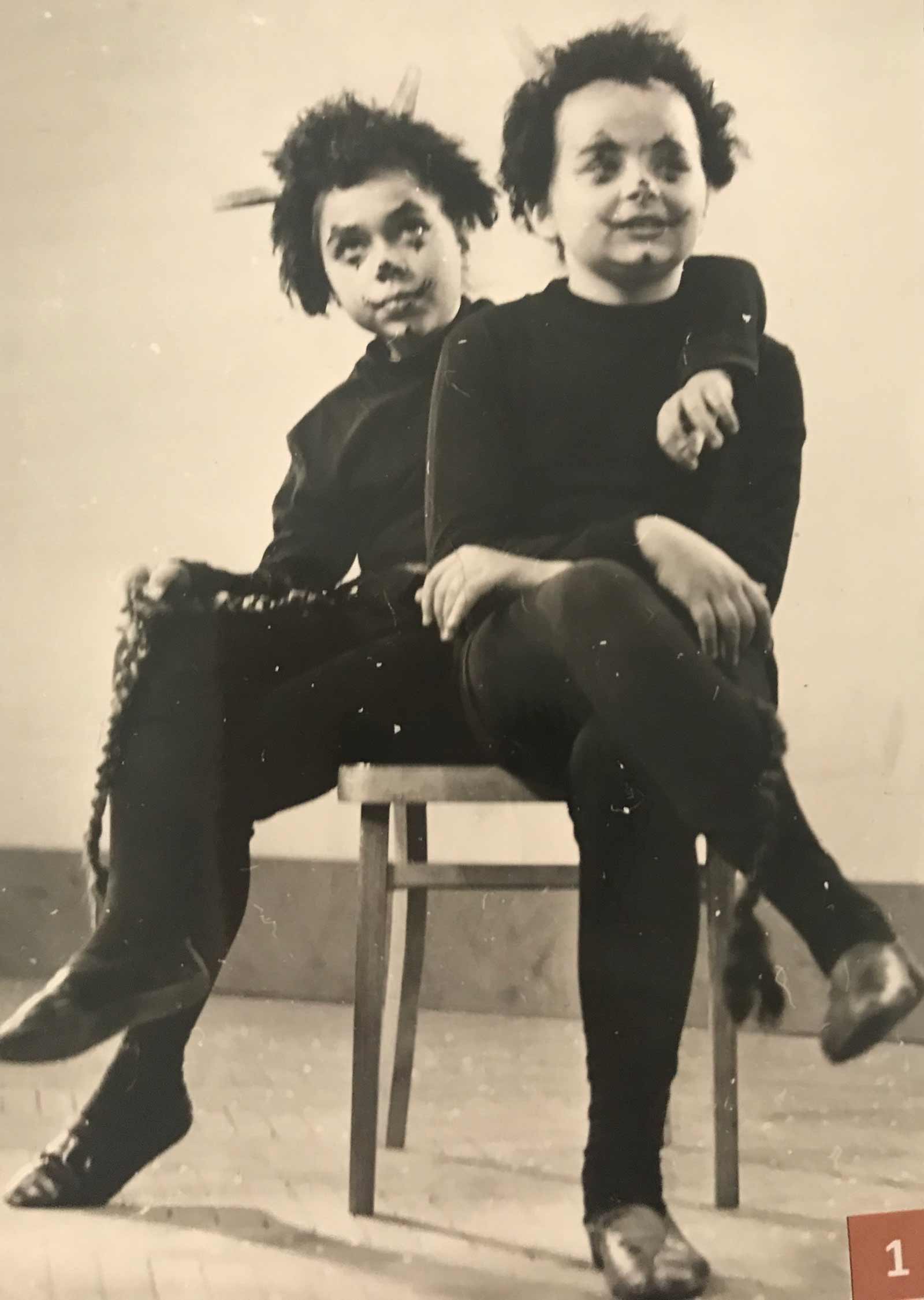

Located on the second floor, the drama circle was no match for the ballet studio, but it had an adjacent theater for 300 people, a real stage with moving decorations, and a dressing-room with thirty individual makeup stations, regularly replenished. There were plenty of wigs, curling irons, props, and costumes, including two princess gowns. I pined for those. But the role of the little devil allotted to me in the holiday production of the “The Black Lake Mystery” musical required only a black tricot and a black top. A curly black wig outfitted with a pair of foam-rubber horns graced my head, and a long braid made of coarse pig hair was sewn to my tricot. I twirled it as I swaggered, jumped, and staged acts of general villainy, aiding a couple of greedy foreigners, the villains of the script, to distract Ivanushka, the protagonist, from his quest for truth and Annoushka.

Those antics, performed thirty-two times over the month of winter vacation, became my entry pass to the Moscow Exhibition trip. Arguing my case for the announcer role, my mother emphasized the endurance of my vocal cords and absence of stage fright. She also promised to line up a boy co-announcer, the son of our neighbors, a family of ethnic Adyghe, a Northwest Caucasian people of Circassian origin, native to the Kuban region. The two of us, a Russian girl and a Circassian boy, would visually represent the unity of Soviet nations on the renowned stage of the Exhibition. It was an offer that the Pioneer Palace’s administration couldn’t refuse: I was in. My cousins in a neighboring town, already reeling from my not visiting for the winter break, were grossly envious.

We started rehearsals in February, when the occasional snowfalls covering the streets of our southern town were shoveled into dirty-brown humps, and continued rehearsing through May, twice a week after school. A specialist from the Department of Theatrical Mass Entertainment at the local Institute of Culture, where my mother taught piano, was engaged to help with programming. In its final iteration, the program included four vocal-choreographic compositions—“Little Cossack,” “Goodbye, Sea,” “Bread Is A Land’s Glory,” and “The Happiest”; four choreographic compositions without vocals but accompanied by a pioneer band—“Stay In Saddle,” “A Circle Dance of Friendship,” “Who To Become?” and “March of Pioneers”; a boy’s solo—“If I Were A Girl”; and, last but not least, a girl’s solo—“Competition.”

Advertisement

My task was to announce these numbers with “ringing optimism,” no small feat given that my voice, though loud, was naturally in a low register. I also took a role in the “Metal Scraps” skit, to be performed between the numbers. Collecting old teapots and pipes that would be melted down and newly forged into rockets and other useful things was a perennial duty of the Soviet pioneer. Most of this scrap metal ended up rusting away in the schoolyard and never made it into the furnaces of our factories, but our skit didn’t go into that.

In the month of June, when cherries and strawberries began to ripen behind the fenced gardens of the private-sector houses, the rehearsals continued without the interruption of school lessons. The entire ensemble, some two hundred people, was taken to the Palace’s camp in Dzhubga (“Valley of Winds” in Circassian) on the Black Sea, about an hour bus ride. There were two rehearsals per day: no one wanted to fall flat on their faces in front of hundreds of Exhibition visitors from all over the USSR. The afternoon rehearsal was in costume. Mine was a standard summer pioneer uniform—a plissé blue skirt, a white blouse, a red neckerchief—minus the side-cap as those had a tendency to slip off in action, interfering with the perfect look.

The singers and dancers wore traditional Kuban Cossack costumes—embroidered red tops, wide black pants cinched at the ankles for boys, flamboyant floating skirts for girls, plus the flower headdresses. Years later, I’d catch glimmers of that look in the opera diva Anna Netrebko, who’d started at the same “Pioneers of Kuban” ensemble with me and went on to deliver her silver-voiced arias from the world’s most celebrated stages. She may have been rehearsing in Dzhubga that June with the rest of us, though if she were, I wasn’t aware of it. On the camp’s stage, under the silk trees already dropping fuzzy pink flowers, dancers twirled in unison, performed long sequences on their haunches, and jumped to the shouts of “hop!” As I exalted—in the required “ringing” voice—the Karasun Ponds, a duckweed-overgrown attraction on the outskirts of town, I believed in their beauty.

Except that, one day, I woke up to the usual sound of the bugle—and found that my ringing tone was gone. My voice didn’t come back during the morning roll call, when my comrades shouted their “Always ready,” or during breakfast, a steaming plate of semolina with a small square of butter melting in the middle. I remained voiceless during the morning rehearsal, watching the program director reading my lines. During the afternoon snack, I drank two glasses of hot milk—to no avail; at the second rehearsal, I gasped and croaked just as I’d done during the morning one. A chorus singer was asked to stand in for me.

After two days, which I spent in a delirium of disappointment listening to the naturally sonorous voice of my substitute and watching my dreams of visiting the Exhibition’s Space Pavilion, with real cosmonaut food and rockets, dissolve into thin air, my mother came to pick me up. The two of us were to go on a planned trip to Leningrad with my aunt and cousins, and from there take the Red Arrow Train to Moscow, to rejoin the ensemble right before the show. But there was no longer any need for us to come, the director informed my mother: the announcer role had gone to the girl from the folk chorus.

It didn’t matter that my mother persuaded the management to give me a chance to try out in Moscow one more time. Or that she was convinced my voice would return if we took necessary measures. I cried all the way on our two-mile walk to the train station. I cried on the dusty platform. And I cried on the train taking us to the nearby port of Novorossiysk, where my aunt and cousins lived, and from where we were scheduled to depart for Leningrad. Even a monkey on the shoulder of an amateur photographer sitting across from us—we were in a resort area—could not distract me from pouring out my grief.

“Look, a monkey,” my mother said in a desperate bid. “Pet her!” When I reached out, the monkey grabbed my finger and bit it. She had a wrinkled, slightly flabbergasted face, and worn but efficient teeth that sank in all the way to the bone. For the first time in two days, staring at the bloody handkerchief that my mother, miserable herself by then, wrapped around my finger, I stopped crying. The photographer muttered something about bratty children and changed seats.

Advertisement

In Novorossiysk, the battle for my vocal cords began. My mother’s therapy was simple: no shouting about the Karasun Ponds, no singing “Rise Up in Bonfires, Thee Blue Nights,” no group cheers, slogans or chants, no loud fighting with my cousins, and, most depressingly, no ice cream. Anything cold, everyone believed, was just as bad for vocal cords as over-exertion. To make my deprivation less painful, she proposed that my cousins abstain from ice cream also. My aunt and uncle said their children should not have to go without just because some people had to make their daughter “a stopper in every barrel,” a Russian version of sticking a finger in every pie.

In addition to enforcing my rest, my mother performed two folk medicine treatments on me: inhalation over boiled potatoes and the blue lamp light. The steaming potato therapy was a staple over the winter months when everyone got respiratory tract diseases, but it was not a pleasant thing during the summer. You hunched over a scalding pot of freshly cooked potatoes, a towel over your head, and inhaled deeply for ten minutes. I didn’t need talking into it, though: blinking salt-stinging sweat off my eyelids, I pictured another girl reciting my lines on the Exhibition’s stage, perhaps even earning herself an invitation to star in a Mosfilm movie, and inhaled even deeper. The blue-light lamp treatment was one of those things that no one completely understood but everyone swore by. As I lay on my back, a cobalt bulb inside a chrome reflector emitting light onto my face and throat, I silently repeated the lines of the “Metal Scraps” skit.

Whether it was the mysterious emanations of the blue lamp, the hot potatoes, or the abstention from ice cream, my vocal cords responded. Boarding the train for Leningrad, I could speak again; my voice was still hoarse, but it was a voice, not a whisper. By the time we made it to our “northern capital,” or rather to the workers’ dorm near the train station with the funny name “Porcelain,” where my grandfather had arranged for two free rooms, I could speak almost normally. From then on, things improved by leaps and bounds.

I remember Leningrad on that trip as a city of majestic ice cream. In the USSR, certain places had better than usual food supply—either because of the presence of foreign tourists, or because of the menace of a nearby chemical or nuclear facility for which the residents had to be compensated somehow. The cities we hailed from boasted neither, so our ice cream choices were basic: “Milky,” “Creamy,” and “Plombir” (vanilla), with occasional appearances of “Fruity,” a sorbet of sorts, and a rather esoteric “Tomato,” which I never dared to try. This ice cream came in soggy wafers or paper cups, into which you dug with wooden sticks, having first peeled off and licked clean the thin paper cover that also acted as a label.

Leningrad, on the other hand, Peter the Great’s famed “window to Europe,” had serious ice cream. There was the legendary chocolate-glazed “Eskimo” on a stick. “Leningradskoye,” chocolate-glazed without a stick, in a colorful foil wrapping. “Crème Brûlé,” a hefty chocolate-covered brick. “Gourmand,” a bar in a chocolate-walnut glaze. According to my cousins, all tasted as good as they looked—but none of them were for me. “Be patient, Cossack, and you’ll become an Ataman [a Cossack leader],” my mother, otherwise immune to folklore, would say and hand me a cup of viburnum berry tea she had brewed in the dorm’s communal kitchen. I hated both the saying and the tea.

Another thing I remember about Leningrad was the lines. We stood in them for hours. At St. Isaac’s Cathedral, where the swaying of a Foucault’s Pendulum proclaimed the victory of science over religion. At Kunstkamera, with its formalin-preserved freaks that Tsar Peter liked collecting. At the Peterhof Palace complex, where my mother had to pretend she was accompanying an important railway official (my aunt) in order to get us in through the side door, so that we wouldn’t die of the heat—surprising in this northern city. At the Hermitage, so vast that if one were to spend a minute in front of every exhibit, it would take a thousand years to see the whole collection, or so the tour guide said. Skidding into one of the galleries in my oversized museum slippers, I recognized the paintings from my stamp album and nearly blew my recovery by shouting, “Look, Mom, the Flemish Primitives!” My cousins howled with laughter.

Amid the imperial splendors of extinct tsars, the specter of ice cream lurked. In the Passage, a pre-revolutionary department store, where my aunt insisted on standing in every line, “Eskimo” ices were sold off multiple carts. Across from the Kazan Cathedral, burial place of Napoleon’s nemesis, General Kutuzov, and now the Museum of Religion and Atheism, the famous “Frog Pond” offered perfect scoops sprinkled with grated chocolate in tall-stemmed metal vases. Not to take me there after all the stories she’d told me about the café was impossible even for a person with my mother’s steely will. As we sat on plush green couches, she ordered two cafés glacés, which I drank through a straw, after the ice cream had melted in hot coffee. I did not protest. We were three days away from my audition in Moscow to win back my part.

The last day of our stay in Leningrad, my mother insisted we have dinner at the Café North, Leningrad’s gastronomical landmark on Nevsky Prospect. Compared to Peterhof, the line was shorter, but after a week of sightseeing, we were tired and hungry. When, after a two-and-a-half-hour wait, a plate of dark rye bread appeared before us, exactly five pieces, we tore into it like wolves, adding repulsion to the deep ennui that seemed to grip our waitress. Our mothers ordered chicken broth and meat-stuffed blinis, the two items on the menu that they could afford—and that we regularly ate at home, so we couldn’t understand what all the fuss was about. A date with the ice-cream tower interspersed by meringue layers was postponed “for next time.”

At midnight, we arrived at Moskovsky Railway Station, from where the Red Arrow sleeper train was to take my restored voice and me to Moscow. When the train pulled in, our car, #10, was nowhere to be seen. There was #9 and #11, but no #10, whichever end of the train you counted from. The attendants in their crinkled blue uniforms shrugged sleepily as we ran up and down the platform and suggested my mother take up the matter with the station management in the morning. Salvation came from my aunt, or rather from her “Honored Railway Worker” ID. It got us on the train two minutes before departure, but once inside, we were on our own. My mother spent the night on a pull-down seat in the corridor, while I fell asleep on the only free berth, above a snoring man who knew nothing about my looming audition, the “Pioneers of Kuban,” and the impending show at the Exhibition of Achievements of the National Economy.

The rest of the ensemble, which had arrived in three train cars between all the children, instruments, and costumes, was housed near the Exhibition in the hotel “Golden Spikelet,” a brick building as unremarkable as our dorm near Porcelain Station. We got there with our suitcases at 7 AM, bleary-eyed but determined. At eight, in the hotel’s lobby, I recited my lines to the show’s director in a firm and ringing voice, just as my mother had promised. At nine, during the roll call, my substitute was relegated back to the chorus. At noon, my mother and I joined the ensemble on an open boat cruise along Moscow River.

If Leningrad was hot, Moscow was hotter. Ninety-eight degrees in the shade was no joke, even by our southern Russian standards. Heavy storm clouds hung over the river, there was barely any wind, and the air smelled of smoke: outside the city, peat bogs were burning. On the boat’s upper deck, just as we were passing the Kremlin, a dancer succumbed to heat stroke, and blood dripped from a nose-bleed onto his white shirt; by the Borovitsky Gate, a girl from the chorus fainted. The two spent the rest of the voyage with wet handkerchiefs over their heads. As we disembarked, the clouds delivered a rain of the strangest kind: we could hear the noise of a downpour, but the raindrops seemed to evaporate before they even hit the ground. “Dry rain,” the boat’s captain said.

At last, the day we’d prepared for over six long months had arrived. At 9 AM sharp, trembling with anticipation, we lined up in front of the Exhibition’s main entrance, a giant triumphant arch topped by the bronze “Tractor Man and Kolkhoz Woman” thrusting forward a bunch of wheat. Behind the arch, at the end of a broad alley, loomed the tiered white building of the Main Pavilion, with more stern-looking statuary placed strategically at the four corners of the upper-level colonnade, above which, at the top of the gilded steeple, soared a shiny star.

At 9:30, an Exhibition official led us across the stadium-sized Square of the Kolkhozes (collective farms). Inside the “Friendship of Nations” fountain, fifteen golden statues symbolizing fifteen Soviet sister-republics, each holding a crop that its republic was most famous for—cotton flowers for Uzbekistan, grapes for Georgia—followed us with their impassive gazes. Another magnificent fountain, “The Stone Flower” from Bazhov’s fairy tale, sprouted gallons of water from its massive granite petals. It was surrounded by smaller, but equally energetic displays of pressurized water, enveloping the entire square and the various pavilions in a pleasant cool mist on what was gearing up to be another very hot day.

Ahead, the slender Vostok space rocket marked the entrance to the Space Pavilion. Accompanied by the lowing and bleating coming from the agricultural exhibits, we turned left and walked past the faux-Roman portico of the Forestry and Timber Pavilion, then past the Hydro-Meteorological Pavilion with a giant globe on the façade, and, in a few more minutes, arrived at the Summer Theater, a shell-shaped half-dome facing rows of wooden benches. About double the capacity of our Pioneer Palace’s theater, it was completely empty at the moment, which made the next three hours of final rehearsal easier. My mother watched the production from the front bench along with the mother of my co-announcer, the two covering their heads with newspaper from the sun.

The show was to start at 2 PM. But at 1:55, the Summer Theater, stark in the afternoon heat, remained empty, save for our mothers. Our director went about frantically dispatching Palace administrators to the Space Pavilion in hopes of roping in some viewers from there. At 2:30, a man in a sports outfit and carrying a pair of skis walked tentatively into the theater and sat down at the edge of a middle row, as if mindful of blocking the view with his unusual cargo for the rest of the hypothetical audience. At 2:45, since he remained our only viewer, the director ordered us to start with a defiant wave of her hand.

“Ponds of Karasun!” my voice rang across the stubbornly empty theater. “Little Cossack Dance!” “Goodbye, Sea! “The Happiest!” On the stage, “Pioneers of Kuban” imitated our fields of golden wheat waving in the breeze, sang the virtues of bread, of morning dew and flower picking, of friendship and unity, of our love for Motherland, and our Great Collective Cause. At times, the man in the sports outfit leaned the skis against his shoulder and joined our mothers in clapping. When my neighbor and I performed our “Metal Scrap” skit, he laughed.

At 4:30, the show was over. The ensemble’s director, agitated and exhausted, shook hands with the mysterious skier before he disappeared into the Exhibition’s green alley. We were splendid, the director proclaimed, our country was proud of us and of the great labors we’d undertaken. She then handed us unclaimed concert programs as souvenirs. We were free to start our exploration of the Exhibition, which would continue tomorrow for the entire day.

My mother, whose face was sunburned despite the newspaper, volunteered to take a group to the Space Pavilion. Ours was a reduced contingent, for the baggy black pants and long-sleeved shirts of the dance section of our vocal-choreographic collective made venturing into much of the sprawling exhibition a health hazard. Just before the Square of Industries, bustling with people who had never made it to our concert, I spotted an ice-cream cart. As we stood in line, all I could see were the foil-wrapped cylinders, handed out by a sweating fairy wearing the white robes of a “collective feeding” sector worker, with a lacy side-cap instead of a crown.

Named after the Battle of Borodino, in which Napoleon got a taste of Russia’s fury, Borodino ice-cream started with a crème brûlée glazing that broke delicately under your teeth as you bit into it, and culminated in a sweet Plombir cream, the smoothest and creamiest of them all. My mother bought two pieces—only one per pair of hands was allowed—and gave me hers after the first bite; she didn’t really like the taste of crème brûlée, she said. Unquestioningly and selfishly, I ate them both, the first one fast, the second slowly, thankful for my mother’s unshakable belief in my vocal cords, the Pioneers’ Palace invitation to the Exhibition, and our National Economy, whose many achievements included the Moscow Refrigeration Plant #6, which had created the masterpiece in my hand. Ahead lay the Space Pavilion, Gagarin’s rocket, and real cosmonaut food. It had all been worth it.