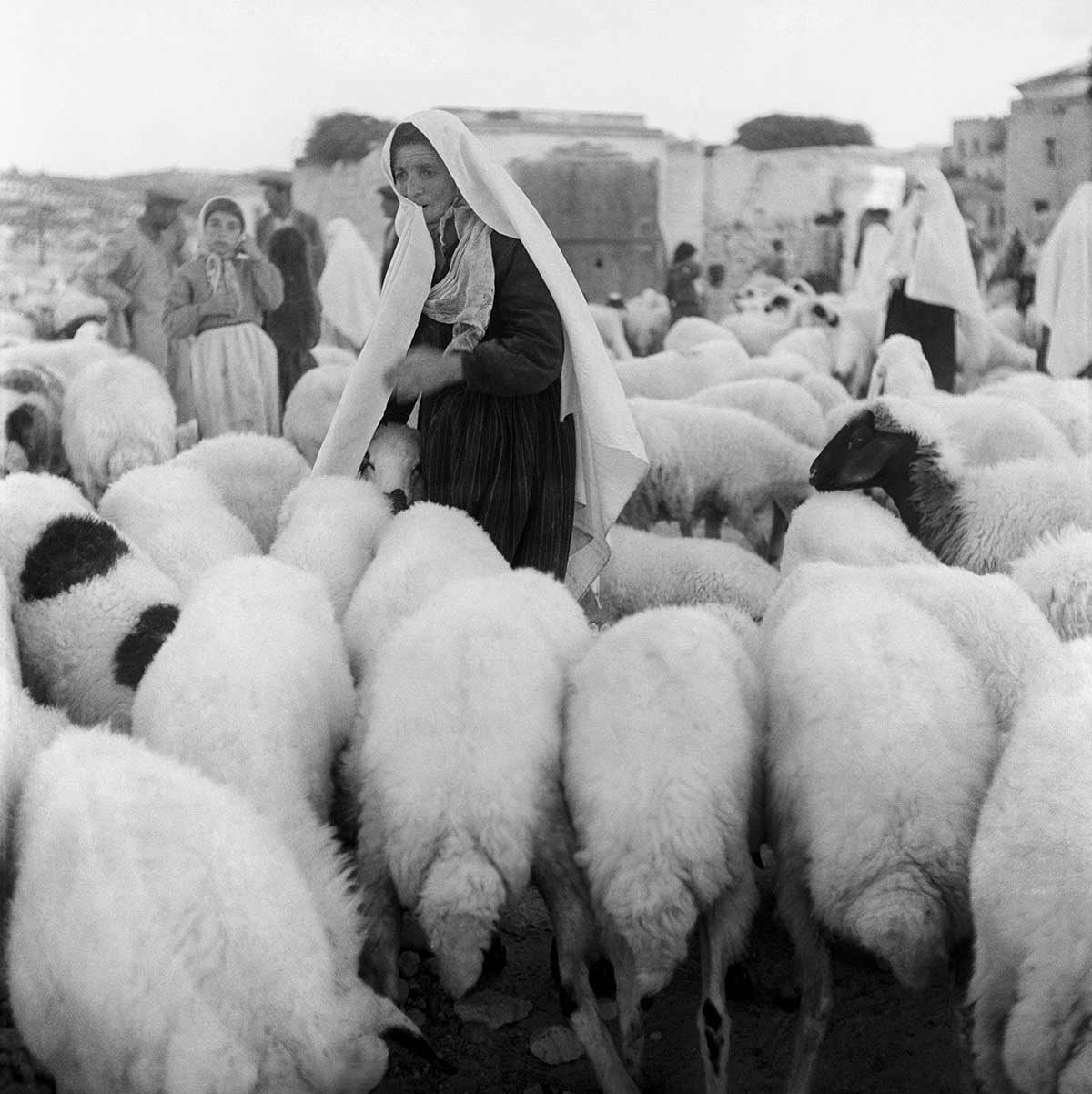

In a photograph taken in Tatvan, a village on the western shore of Lake Van in Eastern Turkey, a matronly figure anxiously clenches between her teeth a corner of her draping white linen kıtan, a traditional head covering worn by women in the region. Her blurred left hand sways over a flock of white sheep around her, their tails turned to the viewer. As your eyes take in more of the picture, you notice the other villagers huddled in the background, as well as her right hand, protectively pressing to her, beneath her cloak, a frightened sheep—the only figure in the entire photograph whose black eyes gaze directly into the lens of the camera.

The understated emotion, technical skill, and semi-abstract texture that animate Tatvan, Bitlis (1956) are typical of all eighty-six photographs by Yıldız Moran, now on display at Istanbul Modern. The first academically trained Turkish female photographer, Moran is enjoying a much deserved revival in Turkey, with some of her photographs being exhibited for the first time. The show is an effort not only to bring to light the work of an outstanding female artist but also to showcase Turkish Republican art. The current retrospective at Istanbul Modern is culled from the nearly 8,000 negatives that Moran left behind upon her death in 1995.

Moran was born in Istanbul in 1932 to a prominent family in the young Turkish Republic. Her father worked in intelligence, but was also an amateur photographer. Moran attended Robert College, the American high school in Istanbul where James Baldwin occasionally lectured on Henry James during his decade-long stay in Turkey in the Sixties. After failing a class during her senior year, she was encouraged by her uncle, a famous art historian, to study photography in England. At eighteen, Moran packed her bags and left Istanbul for London, studying first at the Bloomsbury Technical College and later at Ealing Technical College. This early period was highly productive; she traveled across Portugal, Spain, and Italy taking photographs, and held her first solo exhibition in 1953, a collection of twenty-five images at Trinity College in Cambridge. Istanbul was calling, however, and the following year she returned home to help her uncle with a book he was writing.

Moran’s brief career, which spanned from 1950 to 1962, coincided with major political changes in Turkey. Aligning itself with the West, Turkey joined NATO forces fighting in the Korean War. In 1950, for the first time in its brief history, the Turkish Republic held multi-party elections, ending a twenty-seven-year period of one-party rule. The victorious Democrat Party, led by the populist Adnan Menderes, encouraged migration from rural areas, causing Istanbul’s population to nearly double between 1945 and 1960. Perhaps intrigued by these developments, several of Moran’s contemporaries gravitated toward photojournalism. Semiha Es, Turkey’s first female war photographer, left for the Korean front; Eleni Küreman became a photographer for the Associated Press; Ara Güler, now known as the “Eye of Istanbul,” similarly got his start shooting for local newspapers and magazines, such as Hayat, and later became a photojournalist for Life, Paris Match, and Der Stern.

Despite the sweeping social changes overtaking Turkey during this period, Moran’s photographs do not explicitly address those tectonic shifts. Perhaps due to the technical education she received in England, Moran was instead drawn to unconventional compositions of everyday subjects, both urban and rural. At a time when women in Turkey could not easily travel on their own, she courageously traversed the country, documenting the lives of ordinary people, often women and children. From the image of a young boy standing behind a stall selling fish in the Istanbul night to a man trailing behind a horse wagon in Cappadocia, her photographs are meticulously constructed vignettes that communicate artistic control and emotion without being rigid.

The young photographer, fresh from her apprenticeship in England, soon opened a little atelier above the Maya Gallery on a street behind Istiklal Caddesi, the winding pedestrian avenue that begins in Taksim Square. In the mid-Fifties, Turkish photography was still in its infancy, and materials were often hard to come by. In an interview with the photographer Seyit Ali Ak, Moran complained, “You had to seek out the newest advancements, the newest opportunities. You couldn’t find the paper you wanted; you couldn’t get the supplies you needed… Everyone working in Turkey is a kind of tightrope walker.” Despite those technical challenges, for the next eight years, Moran took commercial portraits to pay the bills while artistically experimenting with spare Anatolian landscapes, Istanbul’s bustling streets, and the working people who populated both.

Moran shot almost exclusively with a Rolleiflex 2.8 Series, famous for its 6×6 square format. This camera, to which she remained loyal throughout the years, greets visitors from a glass display case as they enter the exhibition at Istanbul Modern. In one section of the show, eight photographs are arranged in two rows of four, printed from the negatives in their original format. The images, though covering a range of different locations and subjects, all showcase Moran’s artistic command of light, geometry, and depth. In one taken in Alanya, a resort town on Turkey’s southern coast, the camera is positioned at the edge of a bluff, looking down as the Mediterranean blends into the horizon. A highway of light over the sea, which the eye might mistake for waves, intersects with currents of water that resemble serpentine ski tracks. The curator’s decision to display this photograph alongside figural, en plein air images of women doing laundry emphasizes the seascape’s graceful abstraction.

Advertisement

The careful compositional instinct in Moran’s photographs of these Anatolian women is also complemented by a guarded intimacy. They are stationed by bodies of water with their backs turned to us like the sheep in the Tatvan photo. Moran seems eager to respect their privacy, not to intrude or impose. As she once remarked, “It was a big advantage to be a woman taking photographs of other women, but I always got their permission. Either orally or in writing. We don’t have the right to invade anyone’s private life.”

It strikes me that although Moran obtained approval from her subjects, she still often obscured their faces. Even her portrait of Füreya Koral, a famous Turkish ceramic artist, is taken in profile. In a way, this veiling is a noteworthy gesture for Moran—who had been an assistant to John Vickers in England, a theater photographer best known for his close-ups of actors at the Old Vic Theater—and who admired the dramatic, often symbolic portraits of the Armenian-Canadian photographer Yousuf Karsh. Both of these artists rarely obscured their subjects, choosing to photograph them head-on. While Moran in her studio earned her keep partly from commercial portraits, her work in the field often eschews a direct gaze—although her shots of children are more playful. We cannot see the facial expressions of Moran’s laboring women. As a result, these figures become more archetypical, more rooted to the land. How they hold themselves and what they wear is all we have to go on, along with the laconic caption: Anatolia (1956).

The word used for the Anatolian countryside in Turkish is taşra, an old word, stretching back to the Orkhon inscriptions, where it simply meant “outside.” Although Moran’s images bring to mind the rustic toil in paintings such as Jean-François Millet’s The Gleaners, they do not feel like social commentaries intended to evoke sympathy for the plight of poor villagers. As the literary critic Nurdan Gürbilek notes, in the Fifties when Moran was shooting, the taşra was just beginning to become aware of itself as a distinct social and cultural entity apart from the major urban centers of Istanbul and Ankara, partly due to the fact that rural voters had become an important base of political support for Menderes. Many in the countryside felt “an anger, a rage, an obstinacy” stemming from the distress of their outsider status, an emotion that had not yet reached full expression.

Moran’s subdued images translate, at least partly, that sense of Anatolia’s being forgotten in stark images of depopulated landscapes inhabited by lone figures. The first image you see as you enter the exhibition is that of a barefoot boy in a desert-like area in the province of Van, draped in a loose tunic, his shadow reduced to a slim streak, his hair a wild jumble. The obvious poverty of his surroundings does not seem intended to elicit pity, but curiosity. Where is this child roaming by himself in this vast, arid landscape?

Moran’s camera captured the city with as much originality as it did the country. A majority of her Istanbul pictures focus on fishing supplies, nets, ships, and boats, not sailing majestically down the Bosphorus but suspended on land or piled on shore. From her photo of two woven mussel baskets tied to large rocks to her shot of five cylindrical mesh traps floating between three caiques, there is a palpable desire to elevate the ordinary; a tactile richness characterizes these images as clashing textures—weave and water, stone and rope—come into contact with each other. In another of her Istanbul boat pictures, Moran unexpectedly shoots from beneath the hull of two docked ships, as if the camera were looking up from the sea, with three men returning Moran’s gaze with faint grins.

Advertisement

A Rolleiflex is held at chest level and requires the photographer to peer through a waist-level viewfinder, which makes obtaining the desired angle challenging. Given her refusal to use a tripod, Moran would have had to stay very still to capture these images, in effect transforming her own body into a tripod. Yet the absence of any apparatus also meant that there was nothing standing between her and her subjects, an intimacy amply registered in her images. In 1958, seeking advice on how she might exhibit her work in the United States, Moran boldly wrote to Edward Steichen, then the director of photography at MoMA, who discouragingly replied that her work, although of high quality, was “too much in the standard pattern of a great mass of present day photography to warrant an exhibition” and that her work required “a deeper, more penetrating understanding of the land and people of Turkey.” Of course, nothing could be farther from the truth; Moran’s work, in its quiet, unassuming way, is one of the best artistic representations of Turkey from this period.

In 1963, she married the prominent poet, Özdemir Asaf, and over the next four years gave birth to three sons. Having produced exceptional pictures for twelve years, Moran set aside her career in photography, she noted in an interview, to raise her children. “Photography is not a job you can do halfway. It’s better not to do it at all,” she concluded. Still, how that choice affected her is hard to say. In 1992, she published a massive 862 page book of Turkish synonyms and antonyms, which took her five years to complete. The photographer and translator Samih Rifat was the first to notice that in her thesaurus the words “photograph,” “camera,” “darkroom,” and “film” were nowhere to be found.

“Yıldız Moran: A Mountain Tale” is on view at Istanbul Modern through May 12, 2019.